Remarks on Sanskrit and Pali Loanwords in Khmer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SC22/WG20 N896 L2/01-476 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale De Normalisation

SC22/WG20 N896 L2/01-476 Universal multiple-octet coded character set International organization for standardization Organisation internationale de normalisation Title: Ordering rules for Khmer Source: Kent Karlsson Date: 2001-12-19 Status: Expert contribution Document type: Working group document Action: For consideration by the UTC and JTC 1/SC 22/WG 20 1 Introduction The Khmer script in Unicode/10646 uses conjoining characters, just like the Indic scripts and Hangul. An alternative that is suitable (and much more elegant) for Khmer, but not for Indic scripts, would have been to have combining- below (and sometimes a bit to the side) consonants and combining-below independent vowels, similar to the combining-above Latin letters recently encoded, as well as how Tibetan is handled. However that is not the chosen solution, which instead uses a combining character (COENG) that makes characters conjoin (glue) like it is done for Indic (Brahmic) scripts and like Hangul Jamo, though the latter does not have a separate gluer character. In the Khmer script, using the COENG based approach, the words are formed from orthographic syllables, where an orthographic syllable has the following structure [add ligation control?]: Khmer-syllable ::= (K H)* K M* where K is a Khmer consonant (most with an inherent vowel that is pronounced only if there is no consonant, independent vowel, or dependent vowel following it in the orthographic syllable) or a Khmer independent vowel, H is the invisible Khmer conjoint former COENG, M is a combining character (including COENG, though that would be a misspelling), in particular a combining Khmer vowel (noted A below) or modifier sign. -

Khmer Phonetics & Phonology: Theoretical Implications for ESL Instruction

Running Head: KHMER PHONETICS AND PHONOLOGY 1 Khmer Phonetics & Phonology: Theoretical Implications for ESL Instruction Alex Donley A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2020 KHMER PHONETICS AND PHONOLOGY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Stephanie Blankenship, Ed.D. Committee Member ______________________________ David Schweitzer, Ph.D. Assistant Honors Director ______________________________ Date KHMER PHONETICS AND PHONOLOGY 3 Abstract This thesis develops an approach to English teaching for Khmer-speaking students that centers on Khmer phonetics and phonology. Cambodia has a strong demand for English instruction, but consistently underperforms next to other nations in terms of proficiency. A significant reason for Cambodia’s skill gap is the lack of research into linguistic hurdles Khmer speakers face when learning English. This paper aims to bridge Khmer and English with an understanding of the speech systems that both languages use before turning to the unique challenges Khmer speakers must overcome based on the tenets of L1 Transfer Theory. It closes by outlining strategies for English teachers to build the comprehensibility and confidence of their Khmer-speaking students. Keywords: Khmer, English, phonetics, phonology, transfer, ESL KHMER PHONETICS AND PHONOLOGY 4 Khmer Phonetics and Phonology: Theoretical Implications for ESL Instruction Introduction This thesis develops an approach to English teaching for Khmer-speaking students that is grounded in a thorough understanding of Khmer phonetics and phonology. -

Khmer Romanization Table

KHMER Consonants ʻAksar Mul script ʻAksar Mul script Full Full Full Full Form Subscript form Subscript Romanization Form Subscript form Subscript Romanization ក ◌ក ក ◌្ក k ទ ◌ទ ទ ◌្ទ d ខ ◌ខ ខ ◌្ខ kh ធ ◌ធ ធ ◌្ធ dh គ ◌គ គ ◌្គ g ន ◌ន ន ◌្ន n ឃ ◌ឃ ឃ ◌ឃ gh ប ◌ប ប ◌ប p ង ◌ង ង ◌្ង ng ផ ◌ផ ផ ◌្ផ ph ច ◌ច ច ◌្ច c ព ◌ព ព ◌្ព b ឆ ◌ឆ ឆ ◌្ឆ ch ភ ◌ភ ភ ◌្ភ bh ជ ◌ជ ជ ◌្ជ j ម ◌ម ម ◌្ម m ឈ ◌ឈ ឈ ◌ឈ jh យ ◌យ យ ◌យ y ញ ◌ញ or ញ ញ ◌្ញ or ញ ñ រ ្រ◌ រ ្រ◌ r ដ ◌្ត ដ ◌្ត ṭ ល ◌្ល ល ◌្ល l ឋ ◌្ឋ ឋ ◌្ឋ ṭh វ ◌្វ វ ◌្វ v ឌ ◌្ឌ ឌ ◌្ឌ ḍ ឝ ◌គ ឝ ◌្គ ś * ឍ ◌ ឍ ◌ឍ ḍh ឞ ◌ ឞ ◌្ឞ s*̣ ណ ◌្ណ ណ ◌្ណ ṇ ស ◌ ស ◌ស s ត ◌្ត ត ◌្ត t ហ ◌្ហ ហ ◌្ហ h ḷ (l with ថ ◌ថ ថ ◌្ថ th ឡ - ឡ - dot below) ‛ ʹ (ayn + អ ◌្អ អ ◌្អ soft sign) * Not used since the mid-17th century and is mainly used for Pali and Sanskrit transliteration. Vowels Independent Romanization Independent Romanization ឥ i ឭ ḷ ឦ ī ឮ ḹ ឧ u ឯ ae ឩ ū ឰ ai ឪ ýu ឱ o ឫ ṛ ឳ au ឬ ṝ Dependent Romanization Dependent Romanization ◌◌ ʹaʹ ែ◌ ʹae ◌ា ʹā ៃ◌ ʹai ◌ិ ʹi េ◌ ʹo ◌ី ʹī េ◌ ʹau ◌ឹ ʹẏ ◌ុ◌ំ ʹuṃ ȳ ṃ ◌ឺ ʹ ◌ំ ʹa ◌ុ ʹu ◌ា◌ំ ʹāṃ ◌ូ ʹū ◌ះ ʹaḥ ◌ួ ʹua ◌ិ◌ះ ʹiḥ ʹẏ េ◌ើ ʹoe ◌ឹ◌ះ ḥ ẏ ʹu េ◌ឿ ʹ a ◌ុ◌ះ ḥ េ◌ៀ ʹia េ◌◌ះ ʹeḥ េ◌ ʹe េ◌◌ះ ʹoaḥ Diacritical marks Vernacular Alternative Romanization ◌៉ ◌ុ ″ (hard sign) ◌៊ ◌ុ ′ (soft sign (prime)) ◌៌ r ◌៍ ̊ (circle above) (see Note 5) ◌៎ ’ (alif) ◌៏ ʻ (ayn) ◌៱ ˙ (dot above) (see Note 5) ◌័◌ ă (breve) ◌ៈ à (combining grave accent) ◌◌់ á (combining acute accent) ◌ា◌់ â (modified letter circumflex) Notes 1. -

On the History of Thai Scripts Hans Penth

Dr. Hans Penth giving his address to the audience or the Oriental Dr. Navavan Bandhumedha talking about the different Tai Hotel on 10 July 1986. Languages at the Oriental Hotel on 10 July 1986. On the History of Thai scripts Hans Penth (From lecture delivered during a meeting of groups were living scattered over a vast area, that the Siam Society, held at the Oriental Hotel, on borrowing of local Man letters by local Thai groups Thursday, 10 July 1986) had the effect to produce, right from the outset, a number of slightly different local proto-Thai scripts Dr. Pe nth pointed out in his introductory which were spread out over a large geographical remarks that the history of the alphabets used by area. the Thais throughout Southeast Asia was still insufficiently known but there were many theories. (3) In the decades around 1300 A.D., efforts He hoped he would be excused if he too come up to reform the old proto-Thai script were made in with certain ideas concerning the origin and both Sukhothai and Chiang Mai. These efforts mark development of the scripts used by tlie Thais, from the turning point from proto-Thai script to modern Assam in the west to Tongking in the east, and from Thai script. Yunnan in the north to Thailand in the south, and (4) Also during the decades before or around referred listeners for further information to his article 1300 A.D., the Thais of Sukhothai and the Thais included in H.R.H. Galyani Vadhana's book on of Chiang Mai did something else that was identical: Yunnan. -

Benchmarking of Document Image Analysis Tasks for Palm Leaf Manuscripts from Southeast Asia

Journal of Imaging Article Benchmarking of Document Image Analysis Tasks for Palm Leaf Manuscripts from Southeast Asia Made Windu Antara Kesiman 1,2,* ID , Dona Valy 3,4, Jean-Christophe Burie 1, Erick Paulus 5, Mira Suryani 5, Setiawan Hadi 5, Michel Verleysen 2, Sophea Chhun 4 and Jean-Marc Ogier 1 1 Laboratoire Informatique Image Interaction (L3i), Université de La Rochelle, 17042 La Rochelle, France; [email protected] (J.-C.B.); [email protected] (J.-M.O.) 2 Laboratory of Cultural Informatics (LCI), Universitas Pendidikan Ganesha, Singaraja, Bali 81116, Indonesia; [email protected] 3 Institute of Information and Communication Technologies, Electronic, and Applied Mathematics (ICTEAM), Université Catholique de Louvain, 1348 Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium; [email protected] 4 Department of Information and Communication Engineering, Institute of Technology of Cambodia, Phnom Penh, Cambodia; [email protected] 5 Department of Computer Science, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung 45363, Indonesia; [email protected] (E.P.); [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (S.H.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 15 December 2017; Accepted: 18 February 2018; Published: 22 February 2018 Abstract: This paper presents a comprehensive test of the principal tasks in document image analysis (DIA), starting with binarization, text line segmentation, and isolated character/glyph recognition, and continuing on to word recognition and transliteration for a new and challenging collection of palm leaf manuscripts from Southeast Asia. This research presents and is performed on a complete dataset collection of Southeast Asian palm leaf manuscripts. It contains three different scripts: Khmer script from Cambodia, and Balinese script and Sundanese script from Indonesia. -

The Unicode Standard, Version 3.0, Issued by the Unicode Consor- Tium and Published by Addison-Wesley

The Unicode Standard Version 3.0 The Unicode Consortium ADDISON–WESLEY An Imprint of Addison Wesley Longman, Inc. Reading, Massachusetts · Harlow, England · Menlo Park, California Berkeley, California · Don Mills, Ontario · Sydney Bonn · Amsterdam · Tokyo · Mexico City Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters. However, not all words in initial capital letters are trademark designations. The authors and publisher have taken care in preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode®, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. If these files have been purchased on computer-readable media, the sole remedy for any claim will be exchange of defective media within ninety days of receipt. Dai Kan-Wa Jiten used as the source of reference Kanji codes was written by Tetsuji Morohashi and published by Taishukan Shoten. ISBN 0-201-61633-5 Copyright © 1991-2000 by Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other- wise, without the prior written permission of the publisher or Unicode, Inc. -

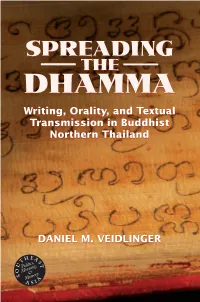

Spreading the Dhamma: Writing, Orality, And

BUDDHISM / SOUTHEAST ASIA VEIDLINGER (Continued from front flap) by forest-dwelling monastic orders in- “There is really nothing like this book. It addresses issues of current How did early Buddhists actually troduced from Sri Lanka in the develop- interest in Buddhist and cultural studies such as textual community, SPREADING encounter the seminal texts of their ment of Lan Na’s written Pali heritage. It literary and material culture, and the relationship between oral religion? What were the attitudes held SPREADING also considers the rivalry between those and written texts. It also brings to scholarly and public attention —— —— by monks and laypeople toward the monks who wished to preserve the older a period and area of the world that has been understudied and is THE written and oral Pali traditions? In this oral tradition and monks, rulers, and deserving of more attention.” pioneering work, Daniel Veidlinger laypeople who supported the expansion explores these questions in the context of the new medium of writing. DONALD K. SWEARER, Harvard Divinity School, Harvard University of the northern Thai kingdom of Lan DHAMMA Na. Drawing on a vast array of sources, Throughout the book, Veidlinger empha- including indigenous chronicles, reports sizes the influence of changing modes of “Spreading the Dhamma is an ambitious and stimulating contribution by foreign visitors, inscriptions, and communication on social and intellectual to the study of Buddhist textual practices in southern Asia. It Writing, Orality, and Textual palm-leaf manuscripts, he traces the role life. The medium, he argues, is deeply in- should provoke further comparative research on the history of of written Buddhist texts in the predomi- volved in the assimilation of the content, writing technologies and attitudes towards writing within the Transmission in Buddhist nantly oral milieu of northern Thailand and therefore the vessels by which texts from the fifteenth to the nineteenth Pali-using Buddhist world.” have been transmitted in the Buddhist Northern Thailand centuries. -

Repha Representation for Kawi

L2/20-283 Repha representation for Kawi Norbert Lindenberg 2020-12-06 This document discusses the options for representing the repha in the Kawi script, which is proposed for encoding in L2/20-284 Proposal to encode Kawi in the UCS. The option chosen is to encode the repha as a separate character with the general category Lo and the Indic syllabic category Consonant_Preceding_Repha, which implies placing this character immediately before the base consonant of the cluster. Repha In Unicode parlance, repha is a special presentation form of a cluster-initial dead consonant ra, which is rendered as a mark above or to the right of a subsequent consonant that serves as the base of the cluster. An extension of the repha concept is the Myanmar kinzi, which applies the same idea to a cluster-initial dead consonant nga for the Burmese language, and to some other consonants in other languages written in the script. In the Balinese, Javanese, and Kawi scripts, marks that originally were a repha have also been used as fnal -r. In these three scripts, the repha or fnal -r is usually positioned above the base consonant. Repha representations for already encoded scripts The Unicode Standard has used a bewildering variety of approaches to representing repha and repha-like marks: 1. An initial ra followed by a dependent vocalic liquid may be rendered as repha above the corresponding independent vocalic liquid, or in the original form, under conditions not specifed in the Unicode Standard. This approach is used for the Bhaiksuki, Devanagari, Gujarati, Kannada, Oriya, and Telugu scripts, although it is only mentioned in the specifcation for Devanagari. -

Ways of Communicating Ideas 2 3 Table of Contents

WAYS OF COMMUNICATING IDEAS 2 3 Table of Contents Cuneiform Family 07 Hieroglyphic Family 13 Eastern Family 23 Arabic Family 37 Indian Family 47 American Family 55 Nordic Family 61 Roman Family 69 Miscellaneous 85 4 5 Cuneiform Family CHAPTER 1 Cuneiform 6 7 Tablet consisting of partial print of the ancient Sumerian Legend of Etana. (1900-1600 Sumerian BC) About 3000 B.C the Sumerians invented a system of writing called Cuneiform. Cuneiform (from the Latin word meaning “wedged- shaped”) was developed from pictographs which later developed into ideographs that conveyed abstracted ideas. The sumerians wrote for left to right and from top to bottom. Cuneiform contains 560 characters which made up the general and only script used. Cuneiform 8 9 Cylinder Seals The seals were first used in Mesopotamia, late 4th century B.C. and spread to Babylonia, Egypt, and western Asia. The seals originally used pictographs, but eventually incorporated letter forms. The original seals were made of shell or lapis lazuli and later Hematite. What was carved into the seals also changed over time. The first were covered with images of how the society was developing (chariots were used). Later on, the images changed to myths and dieties. Text from the Ethnic Studies Library, University of California, Berkeley Cylinder seals were small (2 to 6cm) cylinder-shaped stones carved with decorative designs. They were used as a way for individuals to “sign” their names. The cylinder would simply be rolled over the clay, leaving a raised image behind. The seals were mainly used by royalty and officials as a way to sign documents, such as letter, deeds and records. -

Document Image Analysis and Text Recognition on Khmer Historical Manuscripts

Document Image Analysis and Text Recognition on Khmer Historical Manuscripts A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Docteur en sciences de l’ingénieur et technologie, Université catholique de Louvain January 2020 DONA VALY Thesis committee: Prof. Michel Verleysen (UCLouvain), supervisor Prof. Jean-Pierre Raskin (UCLouvain), chairperson Prof. John Lee (UCLouvain), secretary Prof. Bernard Gosselin (UMons, Belgium) Dr. Sophea Chhun (ITC, Cambodia) List of Figures Figure 2.1: A collection of Khmer palm leaf manuscripts ................... 8 Figure 2.2: Palm leaves are being placed to dry ................................... 9 Figure 2.3: A black mixture is used to make the engraved text easy to read ..................................................................................................... 10 Figure 2.4: Several types of deformations and defects found in palm leaf manuscripts .................................................................................. 13 Figure 2.5: Example of similarity between certain Khmer characters 14 Figure 2.6: Examples of double-decker and triple-decker clusters of Khmer consonants .............................................................................. 15 Figure 2.7: Some examples of ligatures between certain letters which form new shapes ................................................................................. 16 Figure 2.8: Irregular sequential ordering of symbols in a word. The different order of the position of the characters in the text image (top) and the Unicode sequence of the text (bottom) .................................. 17 Figure 2.9: Simulation of how the word “TABLE” could have been written in Khmer style (vowel ‘A’ composed of two parts which are placed on top and on the left side of ‘T’, consonant ‘L’ written as a sub-from under ‘B’, and vowel ‘E’ placed under ‘B’ and the sub-f . 17 Figure 3.1: (a) Sigmoid, (b) Tanh, (c) ReLU, (d) Leaky ReLU ........ -

The Standard Khmer Vowel System: an Acoustic Study CHEM Vatho 1,2 *

Insight: Cambodia Journal of Basic and Applied Research, Volume 2 Number 2 (2020) © 2020 The Authors © 2020 Research Office, Royal University of Phnom Penh (RUPP) The Standard Khmer vowel system: An acoustic study CHEM Vatho 1,2 * 1The Office of Council of Ministers, Friendship Building, 41 Russian Federation Blvd, Phnom Penh, Cambodia. 2Lecturer, Department of International Studies, Institute of Foreign languages at the Royal University of Phnom Penh. *Corresponding Author: CHEM VATHO ([email protected]) To cite this article: Chem, V. (2020). The Standard Khmer Vowel System: An acoustic study. Cambodia Journal of Basic and Applied Research (CJBAR), 2(2), 93–121 សងខិតតេ័យ្ ការសិកាអារូសិទចនលីភាសាស្េមរកនាង្ម្ក (Henderson 1952, Thomas & ź Wanna 1987-88, Ratree 1998, Wo nica 2009, Kirby 2014) ម្ិនាននតោ ត្ នលីប្រោម្ភាសាភនំ ពញជាទប្រម្ង្់សោង្់ោរននភាសាន េះនទ។ ការសិកាននេះវញិ នតោ ត្នលី ការពិពណ៌ ថាន ក់លកណខ ៍ ប្រសៈននសង្ោ ់ោរភាសាស្េមរកុនង្បរបិ ទជាក់ល្លក់ម្ួយនលីប្រោម្ ភាសាភនំ ពញ។ នបីនទាេះបីជាកនាង្ម្ក ម្និ មាននិយម្ន័យចាស់ល្លស់អំពសី ោង្់ោរភាសា ក៏នោយ ក៏នៅស្ត្មានសញ្ជញណ «និោយចាស់» (Speaking Clearly) ស្ែលអាច ជួយបញ្ជា ក់អំពីប្រោម្ភាសាសង្ោ ់ោរននភាសាស្េមរានស្ែរ។ ការសិកាននេះានបងាហ ញ អំពីលទផធ លននការវភាិ រស្បបសូរវទិ ាអារូសចិទ នលីប្រោម្ភាសាភនំ ពញ។ ការសកិ ាននេះ ានរកនឃញី ថា ប្រសៈកុង្ន ភាសាស្េមរ-ភនំនពញ ានបងាហ ញពលី កណខ ៈសទតាទ និង្សូរសាន្រស ត ែូចនៅនឹង្ប្របព័នធប្រសៈកុង្ន ភាសាស្េមរសោង្ោ់ រស្ែរ។ Abstract Previous acoustic studies of the Khmer Language (Henderson 1952, Thomas & Wanna 1987-88, Ratree 1998, Woźnica 2009, Kirby 2014) do not concentrate on the Phnom Penh dialect (hereafter PP dialect) as the canonical form of Khmer. -

Origin of the Brahmi Script

I: STAGES OF EVOLUTION OF BRAHMI Dr. A. RAVISANKAR, Ph.D., The Brahmi script is the earliest writing system developed in India after the Indus script. It is one of the most influential writing systems; all modern Indian scripts and several hundred scripts found in Southeast and East Asia are derived from Brahmi. Rather than representing individual consonant (C) and vowel (V) sounds, its basic writing units represent syllables of various kinds (e.g. CV, CCV, CCCV, CVC, VC). Scripts that operate on this basis are normally classified as syllabic, but because the V and C component of Brahmi symbols are clearly distinguishable, it is classified as an alpha-syllabic writing system. Origin of the Brahmi Script One question about the origin of the Brahmi script relates to whether this system derived from another script or it was an indigenous invention. In the late 19th century CE, Georg Bühler advanced the idea that Brahmi was derived from the Semitic script and adapted by the Brahman scholars to suit the phonetic of Sanskrit and Prakrit. India became exposed to Semitic writing during the 6th century BCE when the Persian Achaemenid Empire took control of the Indus Valley (part of present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northwestern India). Aramaic was the language of ancient Persian government administration, and official records were written using a North Semitic script. Around this time, another script also developed in the region, known as Kharosthi, which remained dominant in the Indus Valley region, while the Brahmi script was employed in the rest of India and other parts of South Asia.