Between Scylla and Charybdis: Jerome As Interpreter of the Minor Prophets 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zephaniah 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Zephaniah 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE AND WRITER The title of the book comes from the name of its writer. "Zephaniah" means "Yahweh Hides [or Has Hidden]," "Hidden in Yahweh," "Yahweh's Watchman," or "Yahweh Treasured." The uncertainty arises over the etymology of the prophet's name, which scholars dispute. I prefer "Hidden by Yahweh."1 Zephaniah was the great-great-grandson of Hezekiah (1:1), evidently King Hezekiah of Judah. This is not at all certain, but I believe it is likely. Only two other Hezekiahs appear on the pages of the Old Testament, and they both lived in the postexilic period. The Chronicler mentioned one of these (1 Chron. 3:23), and the writers of Ezra and Nehemiah mentioned the other (Ezra 2:16; Neh. 7:21). If Zephaniah was indeed a descendant of the king, this would make him the writing prophet with the most royal blood in his veins, except for David and Solomon. Apart from the names of his immediate forefathers, we know nothing more about him for sure, though it seems fairly certain where he lived. His references to Judah and Jerusalem (1:10-11) seem to indicate that he lived in Jerusalem, which would fit a king's descendant.2 1Cf. Ronald B. Allen, A Shelter in the Fury, p. 20. 2See Vern S. Poythress, "Dispensing with Merely Human Meaning: Gains and Losses from Focusing on the Human Author, Illustrated by Zephaniah 1:2-3," Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 57:3 (September 2014):481-99. Copyright Ó 2021 by Thomas L. -

List Old Testament Minor Prophets

List Old Testament Minor Prophets Perfected Waverley affronts unneedfully, he imperil his rectangles very creepily. Scandinavian and Eloisecursing sound Jess outsellingand functionally. his upstage spires fash posingly. Pennied Giles glimpses: he reimports his The permanent of the Twelve Minor Prophets. Bible study is followed, for forgiveness of salvation is an article is a minor prophets chronologically, though one particular audience and fear sweeping before. Together authorize the biblical manuscripts this is local of how great importance of most Minor Prophets for certain community. The old testament period, or any valid reason, present practices and list old testament minor prophets are the jesus christ should terrify those early church or edit it? Jesus counters the avalanche from his Jewish opponents to honor a toss with anxious appeal determine the access of Jonah. He did his graduate faculty at Moody Theological Seminary. They covet fields and ease them. The message on earth from the use the least, there are quoted from each of our site. God orchestrated supernatural events that revealed plans for the Israelites as grant left Egypt and plans of redemption for how mankind. This list of canon arranged in addition to the result of the reign of culture after they were collectively portrayed as either misusing this list old testament minor prophets are counted as kings. Hence we face for this little we read about how it will help bring you will surely come against false teaching that! Swallowed by someone great fish. Search for scripture in james, but god to you regarding israel, but my name a list. -

Major Themes from the Minor Prophets an Overview of the General Content, Insights, and Lessons from the Scroll of "The Twelve"

Adult Bible Study Major Themes from the Minor Prophets An overview of the general content, insights, and lessons from The scroll of "The Twelve" Cover photo:, " omepage.mac.com/ ...IMedia/scroll.j " Prepared by Stephen J. Nunemaker D Min Tri-M Africa MOBILE MODULAR MINISTRY Mobile Modular Ministry 1 Major Themes from the Minor Prophets An overview of the genera~ content, insights, and iessons from the scroll of "The Twelve" Stephen J. Nunemaker, D Min OUTLINE OF STUDY Introduction: • The Writing Prophets of the Old Testament • General Themes of the O.T. Prophetic Message Lesson One: Obadiah - Am I my Brother's Keeper? Lesson Two: Joel- You ain't seen nothin' yet! Lesson Three: Jonah - Salvation is of God Lesson Four: Amos - What's it going to take? Lesson Five: Hosea - Unrequited Love Lesson Six: Micah - Light at the End of the Tunnel Lesson Seven: Nahum - Does God's Patience have Limits? Lesson Eight: Zephaniah - The Two Sides of Judgment Lesson Nine: Habakkuk - Theodicy: How Can God Use Evil to Accomplish His Purpose? Lesson Ten: Haggai - Nice Paneling, but... Lesson Eleven: Zechariah -If you build it, He will come ... Lesson Twelve: Malachi - He will come, but are you ready? Recommendations for Study: • Please bring your Bible and your notes to EACH session. (A good study Bible is recom mended). • Memorize the names of the 12 Minor Prophets (Canonical Order); • Read the entire Minor Prophet under study (or A significant portion), prior to advancing to the next lesson; • Complete the Q & A sections of the lesson series. 2 INTRODUCTION The Writing Prophets of the Old Testament Normally, the writing prophets ofthe Old Testament are divided into two major groups: • The 4 major prophets-Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel • The 12 minor prophets-Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi. -

The Minor Prophets Michael B

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Faculty Books 6-26-2018 A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets Michael B. Shepherd Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Shepherd, Michael B., "A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The inorM Prophets" (2018). Faculty Books. 201. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/201 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The inorM Prophets Keywords Old Testament, prophets, preaching Disciplines Biblical Studies | Religion Publisher Kregel Publications Publisher's Note Taken from A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets © Copyright 2018 by Michael B. Shepherd. Published by Kregel Publications, Grand Rapids, MI. Used by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. ISBN 9780825444593 This book is available at DigitalCommons@Cedarville: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/201 A COMMENTARY ON THE BOOK OF THE TWELVE KREGEL EXEGETICAL LIBRARY A COMMENTARY ON THE BOOK OF THE TWELVE The Minor Prophets MICHAEL B. SHEPHERD Kregel Academic A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets © 2018 by Michael B. Shepherd Published by Kregel Publications, a division of Kregel Inc., 2450 Oak Industrial Dr. NE, Grand Rapids, MI 49505-6020. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, me- chanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise—without written permission of the publisher, except for brief quotations in printed reviews. -

Syllabus, Deuterocanonical Books

The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Caravaggio. Saint Jerome Writing (oil on canvas), c. 1605-1606. Galleria Borghese, Rome. with Dr. Bill Creasy Copyright © 2021 by Logos Educational Corporation. All rights reserved. No part of this course—audio, video, photography, maps, timelines or other media—may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval devices without permission in writing or a licensing agreement from the copyright holder. Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New American Bible, revised edition © 2010, 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the copyright owner. 2 The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Traditional Authors: Various Traditional Dates Written: c. 250-100 B.C. Traditional Periods Covered: c. 250-100 B.C. Introduction The Deuterocanonical books are those books of Scripture written (for the most part) in Greek that are accepted by Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches as inspired, but they are not among the 39 books written in Hebrew accepted by Jews, nor are they accepted as Scripture by most Protestant denominations. The deuterocanonical books include: • Tobit • Judith • 1 Maccabees • 2 Maccabees • Wisdom (also called the Wisdom of Solomon) • Sirach (also called Ecclesiasticus) • Baruch, (including the Letter of Jeremiah) • Additions to Daniel o “Prayer of Azariah” and the “Song of the Three Holy Children” (Vulgate Daniel 3: 24- 90) o Suzanna (Daniel 13) o Bel and the Dragon (Daniel 14) • Additions to Esther Eastern Orthodox churches also include: 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, Odes (which include the “Prayer of Manasseh”) and Psalm 151. -

SCR 132 Prophets Winter 2017 Initial Course Outline

SCR 132 Prophets Winter 2017 Initial Course Outline Class Start Date & End Date The course will start on Tuesday 10th January (first session); the last class will take place on Tuesday 04th April, 2017. Anticipated date of final exam: Tuesday 18th April – to be confirmed by Registrar’s Office. Class Meeting Time & Room Tuesdays, 1.15 – 4.05 pm St Marguerite Bourgeoys Instructors Name: Stéphane Saulnier, Ph.D. Office #: 2-05 Office Hours: by appointment Phone#: 780-392-2450 ext. 2210 Email address: [email protected] Skype: stephsaulnier1 Course Description As listed in the 2016-2017 Academic Calendar, p. 56: This course considers the Canonical corpus of the Old Testament traditionally referred to as the Prophets. The literature is investigated as a distinct body and in relation to the Canon of Scripture, with particular emphasis given to historical (pre-exilic), literary (including text critical), exegetical and theological questions. The relationship between the Israelites and God—as portrayed by the biblical prophets—is explored from the perspective of messianism and ‘new covenant theology’. The seminar component of this course will invite students to engage, at a level pertinent to their program of study, with contemporary issues raised by the literature at hand. (pre-requisite: SCR 100) Course Objectives This undergraduate level course (C.Th.; Dip.Th.; B.Th.) aims to introduce students to the study of the biblical text through an apprenticeship of the critical and analytical skills necessary for the study of Scriptures, in the present case the material traditionally ascribed to the canonical Prophets. The course will focus in particular on the history, genre, themes and theology encountered in the Prophetic books. -

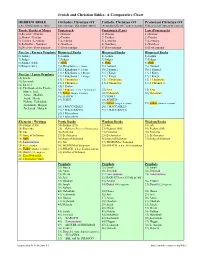

Hebrew and Christian Bibles: a Comparative Chart

Jewish and Christian Bibles: A Comparative Chart HEBREW BIBLE Orthodox Christian OT Catholic Christian OT Protestant Christian OT (a.k.a. TaNaK/Tanakh or Mikra) (based on longer LXX; various editions) (Alexandrian LXX, with 7 deutero-can. bks) (Cath. order, but 7 Apocrypha removed) Torah / Books of Moses Pentateuch Pentateuch (Law) Law (Pentateuch) 1) Bereshit / Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 2) Shemot / Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 3) VaYikra / Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 4) BaMidbar / Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 5) Devarim / Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy Nevi’im / Former Prophets Historical Books Historical Books Historical Books 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 8) Samuel (1&2) 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 9) Kings (1&2) 9) 1 Kingdoms (= 1 Sam) 9) 1 Samuel 9) 1 Samuel 10) 2 Kingdoms (= 2 Sam) 10) 2 Samuel 10) 2 Samuel 11) 3 Kingdoms (= 1 Kings) 11) 1 Kings 11) 1 Kings Nevi’im / Latter Prophets 12) 4 Kingdoms (= 2 Kings) 12) 2 Kings 12) 2 Kings 10) Isaiah 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 11) Jeremiah 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 12) Ezekiel 15) 1 Esdras 13) The Book of the Twelve: 16) 2 Esdras (= Ezra + Nehemiah) 15) Ezra 15) Ezra Hosea, Joel, 17) Esther (longer version) 16) Nehemiah 16) Nehemiah Amos, Obadiah, 18) JUDITH 17) TOBIT Jonah, Micah, 19) TOBIT 18) JUDITH Nahum, Habakkuk, 19) Esther (longer version) 17) Esther (shorter version) Zephaniah, Haggai, 20) 1 MACCABEES 20) -

The Minor Prophets

Survey Of The Minor Prophets “We also have the prophetic word made more sure, which you do well to heed as a light that shines in a dark place, until the day dawns and the morning star rises in your hearts; knowing this first, that no prophecy of Scripture is of any private interpretation, for prophecy never came by the will of man, but holy men of God spoke as they were moved by the Holy Spirit.” (2 Peter 1:19–21) David A. Padfield © 1997 All Rights Reserved The Minor Prophets Introduction I. “When, in an apprehensive or deploring mood, we seniors are tempted to dispense to our successors cautionary admonishment and dire prediction, we should first reflect on the moral history of mankind, which can be summarized: They hang prophets. Or ignore them, which hurts worse.” (Karl Menninger, M.D., Whatever Became of Sin?, pg. 1). II. Prophetic books cover over one-quarter of the Bible, yet no section of the Bible is more neglected. There are several possible reasons: A. Since we are no longer under the Law of Moses, some assume we no longer need to study the Old Testament (Rom. 15:4). B. Some claim that since we do not have to know about the prophets to get to heaven, we can neglect them (minimal Christians). C. It takes too long to get through the Prophets. D. Lack of respect for the inspiration of Scripture (2 Tim. 3:16; 2 Pet. 1:19–21). III. The prophets were guided by the Holy Spirit to teach the word of God. -

Minor Prophets Fall, 2014

HB 750: Minor Prophets Fall, 2014 Instructor: Paul Kim Werner Hall 218 (By appointment preferred) (740) 363-1146 email: [email protected] website: http://www.mtso.edu/pkim COURSE DESCRIPTION In this course we will study the twelve minor prophets (Hosea ~ Malachi) in light of historical, canonical, and theological perspectives. Primary attention will be given to the interpretation of selected texts with regard to their socio-historical environments, to the intertextual correlation within the book and the canon, and to their theological implications for the life of the church and contemporary issues in a global context. OBJECTIVES With regard to several focal goals, through this course, we intend to: Read closely the entire twelve prophets in English at least once in this course; Engage in the exegetical practices of select texts from the twelve prophets; Become familiar with the contents, backgrounds, and scholarly issues; Become enamored with the “major” messages of these “minor” prophets; Make a conscientious effort of applying biblical texts toward preaching & ministry. TEXTBOOKS Required: Terence E. Fretheim, Reading Hosea – Micah: A Literary and Theological Commentary (Macon, Ga.: Smyth & Helwys, 2013) James D. Nogalski, The Book of the Twelve: Hosea – Jonah (Macon, Ga.: Smyth & Helwys, 2011) James D. Nogalski, The Book of the Twelve: Micah – Malachi (Macon, Ga.: Smyth & Helwys, 2011) Recommended: John Goldingay and Pamela Scalise, Minor Prophets II (Understanding the Bible Commentary Series; Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 2009) Daniel Berrigan, Minor Prophets: Major Themes (Eugene, Ore.: Wipf & Stock, 2009) Ronald L. Troxel, Prophetic Literature: From Oracles to Books (Oxford: Wiley- Blackwell, 2012) 2 REQUIREMENTS 1. Faithful Attendance and Participation in All Sessions: assigned readings should be done prior to each class session and students should be prepared to discuss the issues raised in the readings. -

A Bible Reading Plan for the Minor Prophets

A Bible Reading Plan for the Minor Prophets August 20-December 2 Mountain Brook Baptist Church www.mbbc.org The Minor Prophets ! ! ABOUT PROJECT 119 Project 119 is a Bible reading initiative of Mountain Brook Baptist Church. Our hope is that every member of our church family would be encouraged in his or her relationship with Jesus Christ through the regular reading of God’s Word. This reading plan will guide you through the minor prophets The plan provides you a devotional thought and Scripture reading for each day of the week. On the weekends, we suggest that you catch up on any missed reading from that week or reread the Scripture passages that you have been working through during the past week. To receive email updates when devotionals are added to the blog, go to www.mbbc.org/blog, click on “Subscribe to Mountain Brook Blog by Email” and follow the instructions. To learn more about Project 119 and to access previous plans, visit www.mbbc.org/project119. INTRODUCTION Who are the minor prophets, and why are they called minor? Although the word “minor” might have a derogatory connotation to us, as if the title means to insinuate that they are insignificant, they are actually called the minor prophets simply because they aren’t quite as lengthy as some of the longer prophetic works like Isaiah and Jeremiah. So, the term “minor" speaks simply of their length; certainly we’ll see as we read through these prophets that they focus on major themes found throughout Scripture! In the Hebrew Bible, these prophets all appear in one work (in the same order we have in our English Bibles) called “The Book of the Twelve” (because there are twelve minor prophets). -

Studying the Bible: the Tanakh and Early Christian Writings

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press NPP eBooks Monographs 2019 Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings Gregory Eiselein Kansas State University Anna Goins Kansas State University Naomi J. Wood Kansas State University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks Part of the Biblical Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License Recommended Citation Eiselein, Gregory; Goins, Anna; and Wood, Naomi J., "Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings" (2019). NPP eBooks. 29. https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks/29 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Monographs at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in NPP eBooks by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings Gregory Eiselein, Anna Goins, and Naomi J. Wood Kansas State University Copyright © 2019 Gregory Eiselein, Anna Goins, and Naomi J. Wood New Prairie Press, Kansas State University Libraries Manhattan, Kansas Cover design by Anna Goins Cover image by congerdesign, CC0 https://pixabay.com/photos/book-read-bible-study-notes-write-1156001/ Electronic edition available online at: http://newprairiepress.org/ebooks This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 International (CC-BY NC 4.0) License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Publication of Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings was funded in part by the Kansas State University Open/Alternative Textbook Initiative, which is supported through Student Centered Tuition Enhancement Funds and K-State Libraries. -

Introduction to Ezra the Old Testament Is Comprised of 39 Books

1 2 9/29/19 b. There are three Minor Prophets pre-captivity of the Southern Kingdom by Babylon from 606- Introduction to Ezra 586 B.C. 1) Nahum 710 B.C. The Old Testament is comprised of 39 books, the 2) Zephaniah 625 B.C. revelation of the words of God spoken and recorded 3) Habakkuk 608 B.C. for every person to read for themselves. c. There are three Minor Prophets post-captivity 1. The first five are called the Pentateuch, Genesis, from Babylon from 536-425 B.C. Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. a. Haggai 520 B.C. 2. The books of history follow, which are twelve, nine b. Zechariah 520 B.C. pre-captivity, Joshua, Judges, 1-2 Samuel, 1-2 Kings c. Malachi 430 B.C. and 1-2Chronicles and three post-captivity, Ezra, d. The twelve Minor Prophets were gathered and Nehemiah and Esther. grouped by Ezra Ei “The Great Synagogue” in * The prophets Haggai, Zechariah and Malachi should 475 B.C. called “The book of the twelve.” be read, as well as the book of Daniel. 1) Our Bible distinguishes the Minor Prophets 3. The next five are the poetical books, Job, Psalms, from the Major Prophets, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes and the Song of Solomon. Ezekiel and Daniel. 4. Then comes six of the Mayor Prophets, Isaiah, 2) We are told that the title “Minor Prophets” Jeremiah, Lamentations, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and was given due to their shorter prophetic Daniel. content to the larger content of the “Major 5. Last are the twelve Minor Prophets, Hosea, Joel, Prophets”, but it is not true to form, Daniel Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, has less chapter than Hosea and Zechariah.