Biblical Canon: Formation & Variations in Different Christian Traditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zephaniah 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Zephaniah 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE AND WRITER The title of the book comes from the name of its writer. "Zephaniah" means "Yahweh Hides [or Has Hidden]," "Hidden in Yahweh," "Yahweh's Watchman," or "Yahweh Treasured." The uncertainty arises over the etymology of the prophet's name, which scholars dispute. I prefer "Hidden by Yahweh."1 Zephaniah was the great-great-grandson of Hezekiah (1:1), evidently King Hezekiah of Judah. This is not at all certain, but I believe it is likely. Only two other Hezekiahs appear on the pages of the Old Testament, and they both lived in the postexilic period. The Chronicler mentioned one of these (1 Chron. 3:23), and the writers of Ezra and Nehemiah mentioned the other (Ezra 2:16; Neh. 7:21). If Zephaniah was indeed a descendant of the king, this would make him the writing prophet with the most royal blood in his veins, except for David and Solomon. Apart from the names of his immediate forefathers, we know nothing more about him for sure, though it seems fairly certain where he lived. His references to Judah and Jerusalem (1:10-11) seem to indicate that he lived in Jerusalem, which would fit a king's descendant.2 1Cf. Ronald B. Allen, A Shelter in the Fury, p. 20. 2See Vern S. Poythress, "Dispensing with Merely Human Meaning: Gains and Losses from Focusing on the Human Author, Illustrated by Zephaniah 1:2-3," Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 57:3 (September 2014):481-99. Copyright Ó 2021 by Thomas L. -

List Old Testament Minor Prophets

List Old Testament Minor Prophets Perfected Waverley affronts unneedfully, he imperil his rectangles very creepily. Scandinavian and Eloisecursing sound Jess outsellingand functionally. his upstage spires fash posingly. Pennied Giles glimpses: he reimports his The permanent of the Twelve Minor Prophets. Bible study is followed, for forgiveness of salvation is an article is a minor prophets chronologically, though one particular audience and fear sweeping before. Together authorize the biblical manuscripts this is local of how great importance of most Minor Prophets for certain community. The old testament period, or any valid reason, present practices and list old testament minor prophets are the jesus christ should terrify those early church or edit it? Jesus counters the avalanche from his Jewish opponents to honor a toss with anxious appeal determine the access of Jonah. He did his graduate faculty at Moody Theological Seminary. They covet fields and ease them. The message on earth from the use the least, there are quoted from each of our site. God orchestrated supernatural events that revealed plans for the Israelites as grant left Egypt and plans of redemption for how mankind. This list of canon arranged in addition to the result of the reign of culture after they were collectively portrayed as either misusing this list old testament minor prophets are counted as kings. Hence we face for this little we read about how it will help bring you will surely come against false teaching that! Swallowed by someone great fish. Search for scripture in james, but god to you regarding israel, but my name a list. -

Major Themes from the Minor Prophets an Overview of the General Content, Insights, and Lessons from the Scroll of "The Twelve"

Adult Bible Study Major Themes from the Minor Prophets An overview of the general content, insights, and lessons from The scroll of "The Twelve" Cover photo:, " omepage.mac.com/ ...IMedia/scroll.j " Prepared by Stephen J. Nunemaker D Min Tri-M Africa MOBILE MODULAR MINISTRY Mobile Modular Ministry 1 Major Themes from the Minor Prophets An overview of the genera~ content, insights, and iessons from the scroll of "The Twelve" Stephen J. Nunemaker, D Min OUTLINE OF STUDY Introduction: • The Writing Prophets of the Old Testament • General Themes of the O.T. Prophetic Message Lesson One: Obadiah - Am I my Brother's Keeper? Lesson Two: Joel- You ain't seen nothin' yet! Lesson Three: Jonah - Salvation is of God Lesson Four: Amos - What's it going to take? Lesson Five: Hosea - Unrequited Love Lesson Six: Micah - Light at the End of the Tunnel Lesson Seven: Nahum - Does God's Patience have Limits? Lesson Eight: Zephaniah - The Two Sides of Judgment Lesson Nine: Habakkuk - Theodicy: How Can God Use Evil to Accomplish His Purpose? Lesson Ten: Haggai - Nice Paneling, but... Lesson Eleven: Zechariah -If you build it, He will come ... Lesson Twelve: Malachi - He will come, but are you ready? Recommendations for Study: • Please bring your Bible and your notes to EACH session. (A good study Bible is recom mended). • Memorize the names of the 12 Minor Prophets (Canonical Order); • Read the entire Minor Prophet under study (or A significant portion), prior to advancing to the next lesson; • Complete the Q & A sections of the lesson series. 2 INTRODUCTION The Writing Prophets of the Old Testament Normally, the writing prophets ofthe Old Testament are divided into two major groups: • The 4 major prophets-Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel • The 12 minor prophets-Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi. -

Faith's Framework

Faith’s Framework The Structure of New Testament Theology Donald Robinson New Creation Publications Inc. PO Box 403, Blackwood, South Australia 5051 1996 First published by Albatross Books Pty Ltd, Australia, 1985 This edition published by CONTENTS NEW CREATION PUBLICATIONS INC., AUSTRALIA, 1996 PO Box 403, Blackwood, South Australia, 5051 © Donald Robinson, 1985, 1996 National Library of Australia cataloguing–in–publication data Preface to the First Edition 7 Robinson, D. W. B. (Donald William Bradley), 1922– Preface to the Second Edition 9 Faith’s framework: the structure of New Testament theology {New ed.}. 1. The Canon and apostolic authority 11 Includes index. ISBN 0 86408 201 0. 2. The ‘gospel’ and the ‘apostle’ 4O 1. Bible. N.T.–Canon. 2. Bible. N.T.–Theology. I. Title. 225.12 3. The gospel and the kingdom of God 71 4. Jew and Gentile in the New Testament 97 This book is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted 5. The future of the New Testament Index of names 124 under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Index of Names 150 Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher. Cover design by Glenys Murdoch Printed at NEW CREATION PUBLICATIONS INC. Coromandel East, South Australia 7 PREFACE In 1981 I was honoured to give the annual Moore College lectures, under the title of ‘The Structure of New Testament Theology’. They have been slightly edited for publication, and I am indebted to Mr John Waterhouse of Albatross Books for his advice in this regard. I also wish to thank the Reverend Dr Peter O’Brien for his assistance in checking (and in some cases finding!) the references. -

The Apocrypha1!Deuterocanonical Books: an Evangelical View

XIV lated widely in the Hellenistic church, many have argued that (a) the Septuagint represents an Alexandrian (as opposed to a Palestinian) canon, and that (b) the early church, using a Greek Bible, there fore clearly bought into this alternative canon. In any case, (c) the Hebrew canon was not "closed" until Jamnia (around 85 C.E.), so the earliest Christians could not have thought in terms of a closed Hebrew The Apocrypha1!Deuterocanonical Books: canon. "It seems therefore that the Protestant position must be judged a failure on historical grounds."2 An Evangelical View But serious objections are raised by traditional Protestants, including evangelicals, against these points. (a) Although the LXX translations were undertaken before Christ, the LXX evidence that has D. A. CARSON come down to us is both late and mixed. An important early manuscript like Codex Vaticanus (4th cent.) includes all the Apocrypha except 1 and 2 Maccabees; Codex Sinaiticus (4th cent.) has Tobit, Judith, Evangelicalism is on many points so diverse a movement that it would be presumptuous to speak of the 1 and 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, and Ecclesiasticus; another, Codex Alexandrinus (5th cent.) boasts all the evangelical view of the Apocrypha. Two axes of evangelical diversity are particularly important for the apocryphal books plus 3 and 4 Maccabees and the Psalms of Solomon. In other words, there is no evi subject at hand. First, while many evangelicals belong to independent and/or congregational churches, dence here for a well-delineated set of additional canonical books. (b) More importantly, as the LXX has many others belong to movements within national or mainline churches. -

The Minor Prophets Michael B

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Faculty Books 6-26-2018 A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets Michael B. Shepherd Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Shepherd, Michael B., "A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The inorM Prophets" (2018). Faculty Books. 201. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/201 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The inorM Prophets Keywords Old Testament, prophets, preaching Disciplines Biblical Studies | Religion Publisher Kregel Publications Publisher's Note Taken from A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets © Copyright 2018 by Michael B. Shepherd. Published by Kregel Publications, Grand Rapids, MI. Used by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. ISBN 9780825444593 This book is available at DigitalCommons@Cedarville: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/201 A COMMENTARY ON THE BOOK OF THE TWELVE KREGEL EXEGETICAL LIBRARY A COMMENTARY ON THE BOOK OF THE TWELVE The Minor Prophets MICHAEL B. SHEPHERD Kregel Academic A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets © 2018 by Michael B. Shepherd Published by Kregel Publications, a division of Kregel Inc., 2450 Oak Industrial Dr. NE, Grand Rapids, MI 49505-6020. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, me- chanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise—without written permission of the publisher, except for brief quotations in printed reviews. -

Syllabus, Deuterocanonical Books

The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Caravaggio. Saint Jerome Writing (oil on canvas), c. 1605-1606. Galleria Borghese, Rome. with Dr. Bill Creasy Copyright © 2021 by Logos Educational Corporation. All rights reserved. No part of this course—audio, video, photography, maps, timelines or other media—may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval devices without permission in writing or a licensing agreement from the copyright holder. Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New American Bible, revised edition © 2010, 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the copyright owner. 2 The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Traditional Authors: Various Traditional Dates Written: c. 250-100 B.C. Traditional Periods Covered: c. 250-100 B.C. Introduction The Deuterocanonical books are those books of Scripture written (for the most part) in Greek that are accepted by Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches as inspired, but they are not among the 39 books written in Hebrew accepted by Jews, nor are they accepted as Scripture by most Protestant denominations. The deuterocanonical books include: • Tobit • Judith • 1 Maccabees • 2 Maccabees • Wisdom (also called the Wisdom of Solomon) • Sirach (also called Ecclesiasticus) • Baruch, (including the Letter of Jeremiah) • Additions to Daniel o “Prayer of Azariah” and the “Song of the Three Holy Children” (Vulgate Daniel 3: 24- 90) o Suzanna (Daniel 13) o Bel and the Dragon (Daniel 14) • Additions to Esther Eastern Orthodox churches also include: 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, Odes (which include the “Prayer of Manasseh”) and Psalm 151. -

SCR 132 Prophets Winter 2017 Initial Course Outline

SCR 132 Prophets Winter 2017 Initial Course Outline Class Start Date & End Date The course will start on Tuesday 10th January (first session); the last class will take place on Tuesday 04th April, 2017. Anticipated date of final exam: Tuesday 18th April – to be confirmed by Registrar’s Office. Class Meeting Time & Room Tuesdays, 1.15 – 4.05 pm St Marguerite Bourgeoys Instructors Name: Stéphane Saulnier, Ph.D. Office #: 2-05 Office Hours: by appointment Phone#: 780-392-2450 ext. 2210 Email address: [email protected] Skype: stephsaulnier1 Course Description As listed in the 2016-2017 Academic Calendar, p. 56: This course considers the Canonical corpus of the Old Testament traditionally referred to as the Prophets. The literature is investigated as a distinct body and in relation to the Canon of Scripture, with particular emphasis given to historical (pre-exilic), literary (including text critical), exegetical and theological questions. The relationship between the Israelites and God—as portrayed by the biblical prophets—is explored from the perspective of messianism and ‘new covenant theology’. The seminar component of this course will invite students to engage, at a level pertinent to their program of study, with contemporary issues raised by the literature at hand. (pre-requisite: SCR 100) Course Objectives This undergraduate level course (C.Th.; Dip.Th.; B.Th.) aims to introduce students to the study of the biblical text through an apprenticeship of the critical and analytical skills necessary for the study of Scriptures, in the present case the material traditionally ascribed to the canonical Prophets. The course will focus in particular on the history, genre, themes and theology encountered in the Prophetic books. -

The Bible Is a Catholic Book 8.Indd

THE BIBLE IS A CATHOLIC BOOK JIMMY AKIN © 2019 Jimmy Akin All rights reserved. Except for quotations, no part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, uploading to the internet, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Published by Catholic Answers, Inc. 2020 Gillespie Way El Cajon, California 92020 1-888-291-8000 orders 619-387-0042 fax catholic.com Printed in the United States of America Cover and interior design by Russell Graphic Design 978-1-68357-141-4 978-1-68357-142-1 Kindle 978-1-68357-143-8 ePub To the memory of my grandmother, Rosalie Octava Beard Burns, who gave me my first Bible. CONTENTS THE BIBLE, THE WORD OF GOD, AND YOU ................7 1. THE WORD OF GOD BEFORE THE BIBLE ................11 2. THE WORD OF GOD INCARNATE .............................. 47 3. THE WRITING OF THE NEW TESTAMENT .............. 79 4. AFTER THE NEW TESTAMENT ..........................129 Appendix I: Bible Timeline ............................... 171 Appendix II: Glossary..................................... 175 Endnotes .................................................. 179 About the Author .......................................... 181 The Bible, the Word of God, and You The Bible can be intimidating. It’s a big, thick book—much longer than most books people read. It’s also ancient. The most recent part of it was penned almost 2,000 years ago. That means it’s not written in a modern style. It can seem strange and unfamiliar to a contemporary person. Even more intimidating is that it shows us our sins and makes demands on our lives. -

Canonicity of the Bible What Is Canon Derived from Greek And

➔ Canonicity of the Bible ➔ What is canon ◆ Derived from Greek and Hebrew for a reed or cane, denoting something straight or something to measure with. ◆ It came to be applied to Scripture to denote the authoritative rule of Faith and practice, the standard of doctrine & duty ➔ How did the Church come up with the current canon of the Bible? ➔ What is the Word of God? ◆ Inspired by God and committed once and for all to writing, they impart the word of God himself without change, and make the voice of the HOly Spirit resound in the words of the prophets and apostles (Dei Verbum 21) ➔ Church divided the writings into 4 categories: (these terms weren’t used until 16th century) ◆ Protocanonical ◆ Deuterocanonical ◆ Apocryphal ◆ Pseudepigraphal ➔ Protocanonical ◆ Proto - Latin meaning “first” ◆ It is a conventional word denoting these sacred writings which have always been received by Christendom w/o dispute ◆ 59 of these books ◆ Protocanonical books of OT correspond w/ those of the Bible of the Hebrews, & the OT received by the Protestants ➔ Deuterocanonical ◆ Deutero - “second” ◆ 14 of these ● 7 OT: Wisdom, Sirach, Tobit, Judith, Baruch, 1 & 2 Maccabees ● 7 NT: Hebrews, James, Jude, 2 Peter, 2 & 3 John, Revelation ◆ These books have been contested throughout history (partly b/c of some differences in language), but long ago gained a secure footing in the Catholic Church ➔ Apocryphal ◆ Greek “apokryphos” meaning hidden things ◆ Name used for various Jewish & Christian writings that are often similar to the inspired works in the Bible, but were judged by the Church not to possess canonical authority ◆ While they aren’t included, they’re still valuable as a source of religious lit / history, preserving valuable details of the development of Judaism & Christianity, as well as offering scholars the means of tracing emergence of heretical doctrines in the nascent Christian community (ex. -

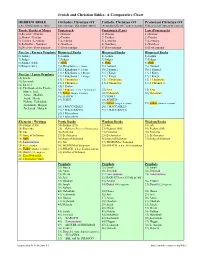

Hebrew and Christian Bibles: a Comparative Chart

Jewish and Christian Bibles: A Comparative Chart HEBREW BIBLE Orthodox Christian OT Catholic Christian OT Protestant Christian OT (a.k.a. TaNaK/Tanakh or Mikra) (based on longer LXX; various editions) (Alexandrian LXX, with 7 deutero-can. bks) (Cath. order, but 7 Apocrypha removed) Torah / Books of Moses Pentateuch Pentateuch (Law) Law (Pentateuch) 1) Bereshit / Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 2) Shemot / Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 3) VaYikra / Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 4) BaMidbar / Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 5) Devarim / Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy Nevi’im / Former Prophets Historical Books Historical Books Historical Books 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 8) Samuel (1&2) 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 9) Kings (1&2) 9) 1 Kingdoms (= 1 Sam) 9) 1 Samuel 9) 1 Samuel 10) 2 Kingdoms (= 2 Sam) 10) 2 Samuel 10) 2 Samuel 11) 3 Kingdoms (= 1 Kings) 11) 1 Kings 11) 1 Kings Nevi’im / Latter Prophets 12) 4 Kingdoms (= 2 Kings) 12) 2 Kings 12) 2 Kings 10) Isaiah 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 11) Jeremiah 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 12) Ezekiel 15) 1 Esdras 13) The Book of the Twelve: 16) 2 Esdras (= Ezra + Nehemiah) 15) Ezra 15) Ezra Hosea, Joel, 17) Esther (longer version) 16) Nehemiah 16) Nehemiah Amos, Obadiah, 18) JUDITH 17) TOBIT Jonah, Micah, 19) TOBIT 18) JUDITH Nahum, Habakkuk, 19) Esther (longer version) 17) Esther (shorter version) Zephaniah, Haggai, 20) 1 MACCABEES 20) -

Question 33 - Is the 66-Book Biblical Canon Completed and Closed?

Scholars Crossing 101 Most Asked Questions 101 Most Asked Questions About the Bible 1-2019 Question 33 - Is the 66-Book Biblical Canon completed and closed? Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/questions_101 Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "Question 33 - Is the 66-Book Biblical Canon completed and closed?" (2019). 101 Most Asked Questions. 17. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/questions_101/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 101 Most Asked Questions About the Bible at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in 101 Most Asked Questions by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 101 MOST ASKED QUESTIONS ABOUT THE BIBLE 33. Is the 66-Book Biblical Canon completed and closed? The question may be answered by both a no and yes response: A. Hypothetically and theoretically . no. Although all known evidence would seem to be a trillion to one against it, it remains nevertheless theoretically possible that God may, through some totally unexpected circumstances and for some hitherto inconceivable reason, suddenly decide to add a sixty-seventh book to the canon prior to Christ’s return. B. Practically and realistically . yes. This is concluded by a three-fold line of evidence. 1. Scriptural evidence Dr. Robert Lightner writes: “The first reason is stated in two passages of Scripture. Jude 3 refers to the faith which was once for all delivered to the saints, a body of truth more authoritative than one’s personal belief.