Vagueness, Ambiguity, and the “Sound” of Meaning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vagueness Susanne Bobzien and Rosanna Keefe

Vagueness Susanne Bobzien and Rosanna Keefe I—SUSANNE BOBZIEN COLUMNAR HIGHER-ORDER VAGUENESS, OR VAGUENESS IS HIGHER-ORDER VAGUENESS Most descriptions of higher-order vagueness in terms of traditional modal logic generate so-called higher-order vagueness paradoxes. The one that doesn’t (Williamson’s) is problematic otherwise. Consequently, the present trend is toward more complex, non-standard theories. However, there is no need for this. In this paper I introduce a theory of higher-order vagueness that is paradox-free and can be expressed in the first-order extension of a normal modal system that is complete with respect to single-domain Kripke-frame semantics. This is the system qs4m+bf+fin. It corresponds to the class of transitive, reflexive and final frames. With borderlineness (unclarity, indeterminacy) defined logically as usual, it then follows that something is borderline precisely when it is higher-order borderline, and that a predicate is vague precisely when it is higher-order vague. Like Williamson’s, the theory proposed here has no clear borderline cas- es in Sorites sequences. I argue that objections that there must be clear bor- derline cases ensue from the confusion of two notions of borderlineness— one associated with genuine higher-order vagueness, the other employed to sort objects into categories—and that the higher-order vagueness para- doxes result from superimposing the second notion onto the first. Lastly, I address some further potential objections. This paper proposes that vagueness is higher-order vagueness. At first blush this may seem a very peculiar suggestion. It is my hope that the following pages will dispel the peculiarity and that the advantages of the proposed theory will speak for themselves. -

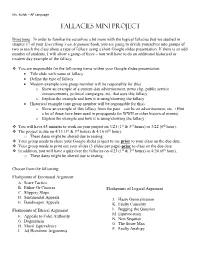

Fallacies Mini Project

Ms. Kizlyk – AP Language Fallacies Mini Project Directions: In order to familiarize ourselves a bit more with the logical fallacies that we studied in chapter 17 of your Everything’s an Argument book, you are going to divide yourselves into groups of two to teach the class about a type of fallacy using a short Google slides presentation. If there is an odd number of students, I will allow a group of three – you will have to do an additional historical or modern day example of the fallacy. You are responsible for the following items within your Google slides presentation: Title slide with name of fallacy Define the type of fallacy Modern example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of a current-day advertisement, news clip, public service announcements, political campaigns, etc. that uses this fallacy o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy Historical example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of this fallacy from the past – can be an advertisement, etc. (Hint – a lot of these have been used in propaganda for WWII or other historical events). o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy You will have 45 minutes to work on your project on 3/21 (1st & 3rd hours) or 3/22 (6th hour). The project is due on 4/13 (1st & 3rd hours) & 4/16 (6th hour). o These dates might be altered due to testing. Your group needs to share your Google slides project to me prior to your class on the due date. -

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center Ad hominem (Argument to the person): Attacking the person making the argument rather than the argument itself. We would take her position on child abuse more seriously if she weren’t so rude to the press. Ad populum appeal (appeal to the public): Draws on whatever people value such as nationality, religion, family. A vote for Joe Smith is a vote for the flag. Alleged certainty: Presents something as certain that is open to debate. Everyone knows that… Obviously, It is obvious that… Clearly, It is common knowledge that… Certainly, Ambiguity and equivocation: Statements that can be interpreted in more than one way. Q: Is she doing a good job? A: She is performing as expected. Appeal to fear: Uses scare tactics instead of legitimate evidence. Anyone who stages a protest against the government must be a terrorist; therefore, we must outlaw protests. Appeal to ignorance: Tries to make an incorrect argument based on the claim never having been proven false. Because no one has proven that food X does not cause cancer, we can assume that it is safe. Appeal to pity: Attempts to arouse sympathy rather than persuade with substantial evidence. He embezzled a million dollars, but his wife had just died and his child needed surgery. Begging the question/Circular Logic: Proof simply offers another version of the question itself. Wrestling is dangerous because it is unsafe. Card stacking: Ignores evidence from the one side while mounting evidence in favor of the other side. Users of hearty glue say that it works great! (What is missing: How many users? Great compared to what?) I should be allowed to go to the party because I did my math homework, I have a ride there and back, and it’s at my friend Jim’s house. -

Two-Dimensionalism: Semantics and Metasemantics

Two-Dimensionalism: Semantics and Metasemantics YEUNG, \y,ang -C-hun ...:' . '",~ ... ~ .. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy In Philosophy The Chinese University of Hong Kong January 2010 Abstract of thesis entitled: Two-Dimensionalism: Semantics and Metasemantics Submitted by YEUNG, Wang Chun for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in July 2009 This ,thesis investigates problems surrounding the lively debate about how Kripke's examples of necessary a posteriori truths and contingent a priori truths should be explained. Two-dimensionalism is a recent development that offers a non-reductive analysis of such truths. The semantic interpretation of two-dimensionalism, proposed by Jackson and Chalmers, has certain 'descriptive' elements, which can be articulated in terms of the following three claims: (a) names and natural kind terms are reference-fixed by some associated properties, (b) these properties are known a priori by every competent speaker, and (c) these properties reflect the cognitive significance of sentences containing such terms. In this thesis, I argue against two arguments directed at such 'descriptive' elements, namely, The Argument from Ignorance and Error ('AlE'), and The Argument from Variability ('AV'). I thereby suggest that reference-fixing properties belong to the semantics of names and natural kind terms, and not to their metasemantics. Chapter 1 is a survey of some central notions related to the debate between descriptivism and direct reference theory, e.g. sense, reference, and rigidity. Chapter 2 outlines the two-dimensional approach and introduces the va~ieties of interpretations 11 of the two-dimensional framework. -

Scope Ambiguity in Syntax and Semantics

Scope Ambiguity in Syntax and Semantics Ling324 Reading: Meaning and Grammar, pg. 142-157 Is Scope Ambiguity Semantically Real? (1) Everyone loves someone. a. Wide scope reading of universal quantifier: ∀x[person(x) →∃y[person(y) ∧ love(x,y)]] b. Wide scope reading of existential quantifier: ∃y[person(y) ∧∀x[person(x) → love(x,y)]] 1 Could one semantic representation handle both the readings? • ∃y∀x reading entails ∀x∃y reading. ∀x∃y describes a more general situation where everyone has someone who s/he loves, and ∃y∀x describes a more specific situation where everyone loves the same person. • Then, couldn’t we say that Everyone loves someone is associated with the semantic representation that describes the more general reading, and the more specific reading obtains under an appropriate context? That is, couldn’t we say that Everyone loves someone is not semantically ambiguous, and its only semantic representation is the following? ∀x[person(x) →∃y[person(y) ∧ love(x,y)]] • After all, this semantic representation reflects the syntax: In syntax, everyone c-commands someone. In semantics, everyone scopes over someone. 2 Arguments for Real Scope Ambiguity • The semantic representation with the scope of quantifiers reflecting the order in which quantifiers occur in a sentence does not always represent the most general reading. (2) a. There was a name tag near every plate. b. A guard is standing in front of every gate. c. A student guide took every visitor to two museums. • Could we stipulate that when interpreting a sentence, no matter which order the quantifiers occur, always assign wide scope to every and narrow scope to some, two, etc.? 3 Arguments for Real Scope Ambiguity (cont.) • But in a negative sentence, ¬∀x∃y reading entails ¬∃y∀x reading. -

On the Logic of Two-Dimensional Semantics

Matrices and Modalities: On the Logic of Two-Dimensional Semantics MSc Thesis (Afstudeerscriptie) written by Peter Fritz (born March 4, 1984 in Ludwigsburg, Germany) under the supervision of Dr Paul Dekker and Prof Dr Yde Venema, and submitted to the Board of Examiners in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MSc in Logic at the Universiteit van Amsterdam. Date of the public defense: Members of the Thesis Committee: June 29, 2011 Dr Paul Dekker Dr Emar Maier Dr Alessandra Palmigiano Prof Dr Frank Veltman Prof Dr Yde Venema Abstract Two-dimensional semantics is a theory in the philosophy of language that pro- vides an account of meaning which is sensitive to the distinction between ne- cessity and apriority. Usually, this theory is presented in an informal manner. In this thesis, I take first steps in formalizing it, and use the formalization to present some considerations in favor of two-dimensional semantics. To do so, I define a semantics for a propositional modal logic with operators for the modalities of necessity, actuality, and apriority that captures the relevant ideas of two-dimensional semantics. I use this to show that some criticisms of two- dimensional semantics that claim that the theory is incoherent are not justified. I also axiomatize the logic, and compare it to the most important proposals in the literature that define similar logics. To indicate that two-dimensional semantics is a plausible semantic theory, I give an argument that shows that all theorems of the logic can be philosophically justified independently of two-dimensional semantics. Acknowledgements I thank my supervisors Paul Dekker and Yde Venema for their help and encour- agement in preparing this thesis. -

The “Ambiguity” Fallacy

\\jciprod01\productn\G\GWN\88-5\GWN502.txt unknown Seq: 1 2-SEP-20 11:10 The “Ambiguity” Fallacy Ryan D. Doerfler* ABSTRACT This Essay considers a popular, deceptively simple argument against the lawfulness of Chevron. As it explains, the argument appears to trade on an ambiguity in the term “ambiguity”—and does so in a way that reveals a mis- match between Chevron criticism and the larger jurisprudence of Chevron critics. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................. 1110 R I. THE ARGUMENT ........................................ 1111 R II. THE AMBIGUITY OF “AMBIGUITY” ..................... 1112 R III. “AMBIGUITY” IN CHEVRON ............................. 1114 R IV. RESOLVING “AMBIGUITY” .............................. 1114 R V. JUDGES AS UMPIRES .................................... 1117 R CONCLUSION ................................................... 1120 R INTRODUCTION Along with other, more complicated arguments, Chevron1 critics offer a simple inference. It starts with the premise, drawn from Mar- bury,2 that courts must interpret statutes independently. To this, critics add, channeling James Madison, that interpreting statutes inevitably requires courts to resolve statutory ambiguity. And from these two seemingly uncontroversial premises, Chevron critics then infer that deferring to an agency’s resolution of some statutory ambiguity would involve an abdication of the judicial role—after all, resolving statutory ambiguity independently is what judges are supposed to do, and defer- ence (as contrasted with respect3) is the opposite of independence. As this Essay explains, this simple inference appears fallacious upon inspection. The reason is that a key term in the inference, “ambi- guity,” is critically ambiguous, and critics seem to slide between one sense of “ambiguity” in the second premise of the argument and an- * Professor of Law, Herbert and Marjorie Fried Research Scholar, The University of Chi- cago Law School. -

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning Caitlyn Nunn, Chloe Christensen, Reece Taylor, and Jade Ballard Definition

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning Caitlyn Nunn, Chloe Christensen, Reece Taylor, and Jade Ballard Definition ● A (normally) comical fallacy in which a proposition is backed by a premise or premises that are backed by the same proposition. Thus creating a cycle where no new or useful information is shared. Universal Example ● “Pvt. Joe Bowers: What are these electrolytes? Do you even know? Secretary of State: They're... what they use to make Brawndo! Pvt. Joe Bowers: But why do they use them to make Brawndo? Secretary of Defense: [raises hand after a pause] Because Brawndo's got electrolytes” (Example from logically fallicious.com from the movie Idiocracy). Circular Reasoning in The Crucible Quote: One committing the fallacy: Elizabeth Hale: But, woman, you do believe there are witches in- Explanation: Elizabeth believes that Elizabeth: If you think that I am one, there are no witches in Salem because then I say there are none. she knows that she is not a witch. She doesn’t think that she’s a witch (p. 200, act 2, lines 65-68) because she doesn’t believe that there are witches in Salem. And so on. More examples from The Crucible Quote: One committing the fallacy: Martha Martha Corey: I am innocent to a witch. I know not what a witch is. Explanation: This conversation Hawthorne: How do you know, then, between Martha and Hathorne is an that you are not a witch? example of begging the question. In Martha Corey: If I were, I would know it. Martha’s answer to Judge Hathorne, she uses false logic. -

The Ambiguous Nature of Language

International J. Soc. Sci. & Education 2017 Vol.7 Issue 4, ISSN: 2223-4934 E and 2227-393X Print The Ambiguous Nature of Language By Mohammad Awwad Applied Linguistics, English Department, Lebanese University, Beirut, LEBANON. [email protected] Abstract Linguistic ambiguity is rendered as a problematic issue since it hinders precise language processing. Ambiguity leads to a confusion of ideas in the reader’s mind when he struggles to decide on the precise meaning intended behind an utterance. In the literature relevant to the topic, no clear classification of linguistic ambiguity can be traced, for what is considered syntactic ambiguity, for some linguists, falls under pragmatic ambiguity for others; what is rendered as lexical ambiguity for some linguists is perceived as semantic ambiguity for others and still as unambiguous to few. The problematic issue, hence, can be recapitulated in the abstruseness hovering around what is linguistic ambiguity, what is not, and what comprises each type of ambiguity in language. The present study aimed at propounding lucid classification of ambiguity types according to their function in context by delving into ambiguity types which are displayed in English words, phrases, clauses, and sentences. converges in an attempt to disambiguate English language structures, and thus provide learners with a better language processing outcome and enhance teachers with a more facile and lucid teaching task. Keywords: linguistic ambiguity, language processing. 1. Introduction Ambiguity is derived from ‘ambiagotatem’ in Latin which combined ‘ambi’ and ‘ago’ each word meaning ‘around’ or ‘by’ (Atlas,1989) , and thus the concept of ambiguity is hesitation, doubt, or uncertainty and that concept associated the term ‘ambiguous’ from the first usage until the most recent linguistic definition. -

Some Common Fallacies of Argument Evading the Issue: You Avoid the Central Point of an Argument, Instead Drawing Attention to a Minor (Or Side) Issue

Some Common Fallacies of Argument Evading the Issue: You avoid the central point of an argument, instead drawing attention to a minor (or side) issue. ex. You've put through a proposal that will cut overall loan benefits for students and drastically raise interest rates, but then you focus on how the system will be set up to process loan applications for students more quickly. Ad hominem: Here you attack a person's character, physical appearance, or personal habits instead of addressing the central issues of an argument. You focus on the person's personality, rather than on his/her ideas, evidence, or arguments. This type of attack sometimes comes in the form of character assassination (especially in politics). You must be sure that character is, in fact, a relevant issue. ex. How can we elect John Smith as the new CEO of our department store when he has been through 4 messy divorces due to his infidelity? Ad populum: This type of argument uses illegitimate emotional appeal, drawing on people's emotions, prejudices, and stereotypes. The emotion evoked here is not supported by sufficient, reliable, and trustworthy sources. Ex. We shouldn't develop our shopping mall here in East Vancouver because there is a rather large immigrant population in the area. There will be too much loitering, shoplifting, crime, and drug use. Complex or Loaded Question: Offers only two options to answer a question that may require a more complex answer. Such questions are worded so that any answer will implicate an opponent. Ex. At what point did you stop cheating on your wife? Setting up a Straw Person: Here you address the weakest point of an opponent's argument, instead of focusing on a main issue. -

Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I

Essential Logic Ronald C. Pine Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I All effective propaganda must be confined to a few bare necessities and then must be expressed in a few stereotyped formulas. Adolf Hitler Until the habit of thinking is well formed, facing the situation to discover the facts requires an effort. For the mind tends to dislike what is unpleasant and so to sheer off from an adequate notice of that which is especially annoying. John Dewey, How We Think Introduction In everyday speech you may have heard someone refer to a commonly accepted belief as a fallacy. What is usually meant is that the belief is false, although widely accepted. In logic, a fallacy refers to logically weak argument appeal (not a belief or statement) that is widely used and successful. Here is our definition: A logical fallacy is an argument that is usually psychologically persuasive but logically weak. By this definition we mean that fallacious arguments work in getting many people to accept conclusions, that they make bad arguments appear good even though a little commonsense reflection will reveal that people ought not to accept the conclusions of these arguments as strongly supported. Although logicians distinguish between formal and informal fallacies, our focus in this chapter and the next one will be on traditional informal fallacies.1 For our purposes, we can think of these fallacies as "informal" because they are most often found in the everyday exchanges of ideas, such as newspaper editorials, letters to the editor, political speeches, advertisements, conversational disagreements between people in social networking sites and Internet discussion boards, and so on. -

• Today: Language, Ambiguity, Vagueness, Fallacies

6060--207207 • Today: language, ambiguity, vagueness, fallacies LookingLooking atat LanguageLanguage • argument: involves the attempt of rational persuasion of one claim based on the evidence of other claims. • ways in which our uses of language can enhance or degrade the quality of arguments: Part I: types and uses of definitions. Part II: how the improper use of language degrades the "weight" of premises. AmbiguityAmbiguity andand VaguenessVagueness • Ambiguity: a word, term, phrase is ambiguous if it has 2 or more well-defined meaning and it is not clear which of these meanings is to be used. • Vagueness: a word, term, phrase is vague if it has more than one possible and not well-defined meaning and it is not clear which of these meanings is to be used. • [newspaper headline] Defendant Attacked by Dead Man with Knife. • Let's have lunch some time. • [from an ENGLISH dept memo] The secretary is available for reproduction services. • [headline] Father of 10 Shot Dead -- Mistaken for Rabbit • [headline] Woman Hurt While Cooking Her Husband's Dinner in a Horrible Manner • advertisement] Jack's Laundry. Leave your clothes here, ladies, and spend the afternoon having a good time. • [1986 headline] Soviet Bloc Heads Gather for Summit. • He fed her dog biscuits. • ambiguous • vague • ambiguous • ambiguous • ambiguous • ambiguous • ambiguous • ambiguous AndAnd now,now, fallaciesfallacies • What are fallacies or what does it mean to reason fallaciously? • Think in terms of the definition of argument … • Fallacies Involving Irrelevance • or, Fallacies of Diversion • or, Sleight-of-Hand Fallacies • We desperately need a nationalized health care program. Those who oppose it think that the private sector will take care of the needs of the poor.