Viewer for the Times Literary Supplement, the Times Higher Education Supplement, Notes and Queries, and Modern Language Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

DESPERATION ROAD MICHAEL FARRIS SMITH MARKETING & SALES POINTS Longlisted for the CWA Gold Dagger 2017

DESPERATION ROAD MICHAEL FARRIS SMITH MARKETING & SALES POINTS Longlisted for the CWA Gold Dagger 2017 'Every once in a while an author comes along who's in love with art and written language and imagery... writers like William Faulkner and Cormac McCarthy and Annie Proulx. You can add Michael Farris Smith's name to the list' - James Lee Burke For fans of Cormac McCarthy, Daniel Woodrell and Annie Proulx Michael Farris Smith's previous novel, Rivers, won the 2014 Mississippi Authors Award for Fiction and was named a Best Book of 2013 by Esquire, Daily Candy, BookRiot, and Hudson Booksellers THE BOOK In the vein of Daniel Woodrell's Winter's Bone and the works of Ron Rash, a novel set in a rough- and-tumble Mississippi town where drugs, whiskey, guns, and the desire for revenge violently intersect For eleven years the clock has been ticking for Russell Gaines as he sat in Parchman penitentiary in the Download high resolution image Mississippi Delta. His time now up, and believing his debt paid, he returns home only to discover that Pub. Date: 23 February 2017 revenge lives and breathes all around. Price: £14.99 ISBN: 978-1-84344-987-4 On the day of his release, a woman named Maben and her young daughter trudge along the side of the Binding: Hardback interstate under the punishing summer sun. Desperate and exhausted, the pair spend their last dollar on Format: Royal (234 x 153mm) a motel room for the night, a night that ends with Maben running through the darkness holding a pistol, Extent: 288 and a dead deputy sprawled across the road in the glow of his own headlights. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

Classical Goddesses in American Short Fiction

CLASSICAL GODDESSES IN AMERICAN SHORT FICTION ABOUT THE VIETNAM WAR by ANDREA DEAN FONTENOT, B.S., M.F.A. A DISSERTATION IN ENGLISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approv94? August, 1998 Ac cop' '^ Copyright 1998 by Andrea Dean Fontenot ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to Dr. Wendell Aycock for his support, patience, and guidance during the preparation for this work. I want to extend my appreciation to Dr. Bryce Conrad and Dr. Michael Schoenecke who, along with Dr. Aycock, allowed me the opportunity to explore a subject that interests me and who gave me insightflil and conscientious direction during the revision process. I want to extend my gratitude to Dr. William Marcy, Dean of the College of Engineering, for allowing me to take much needed time away from my position in order to complete this degree, and for the unending support that he and the College of Engineering have extended to me. I want to thank John Chandler for his support. Finally, I want to thank my family, especially my mother Ruby McDowell for always reminding me that it is never too late to learn and never too late to accomplish seemingly impossible tasks. And I want to especially thank Ron Fontenot for his many years of support and encouragement. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1 n PERSEPHONE: THE MAIDEN AND INNOCENCE 29 m DEMETER: THE MOTHER AND EXPERIENCE 64 IV HECATE: THE WISE CRONE AND RECONSTRUCTION 99 V. -

Draft Syllabi Are Provided to Assist Students in the Course Registration Process

Please Note: Draft syllabi are provided to assist students in the course registration process. Final syllabi will be provided by instructors. Wesleyan University, Graduate Liberal Studies HUMS622: Writing and Revision Brando Skyhorse Tuesdays and Thursdays, 6:30pm-9:30pm June 26-August1; No Class July 4 Course Description Revision is considered the final stage of writing but what is it, exactly? What does the process entail? What constitutes a revision? How do other writers revise? And what are the rules writers can follow to make revision a cornerstone of their writing process? You’ll find out in this class. Revision, simply, is not correction. Revision is not changing “red” to “crimson” or running your spell checker. Revision is a change in your point-of-view. This class’s goal is to help you learn how to change your point-of-view. Through a series of writing exercises, classroom discussions, and applying a specific checklist of revision oriented questions, the goal is to help you understand how revision works, and how you can develop your own revision process to apply to both fiction and non-fiction writing. This is a graduate level writing course. We’ll be focusing on short stories and personal essays but the bulk of our course will be based on a short story of fiction OR a non-fiction essay that you write and revise over the course of a semester. Think of our five week, ten session class as an arc of a story. YOUR story. In the first week you’ll write the first draft of a short story or personal essay. -

Pulitzer Prize

1946: no award given 1945: A Bell for Adano by John Hersey 1944: Journey in the Dark by Martin Flavin 1943: Dragon's Teeth by Upton Sinclair Pulitzer 1942: In This Our Life by Ellen Glasgow 1941: no award given 1940: The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck 1939: The Yearling by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Prize-Winning 1938: The Late George Apley by John Phillips Marquand 1937: Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell 1936: Honey in the Horn by Harold L. Davis Fiction 1935: Now in November by Josephine Winslow Johnson 1934: Lamb in His Bosom by Caroline Miller 1933: The Store by Thomas Sigismund Stribling 1932: The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck 1931 : Years of Grace by Margaret Ayer Barnes 1930: Laughing Boy by Oliver La Farge 1929: Scarlet Sister Mary by Julia Peterkin 1928: The Bridge of San Luis Rey by Thornton Wilder 1927: Early Autumn by Louis Bromfield 1926: Arrowsmith by Sinclair Lewis (declined prize) 1925: So Big! by Edna Ferber 1924: The Able McLaughlins by Margaret Wilson 1923: One of Ours by Willa Cather 1922: Alice Adams by Booth Tarkington 1921: The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton 1920: no award given 1919: The Magnificent Ambersons by Booth Tarkington 1918: His Family by Ernest Poole Deer Park Public Library 44 Lake Avenue Deer Park, NY 11729 (631) 586-3000 2012: no award given 1980: The Executioner's Song by Norman Mailer 2011: Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 1979: The Stories of John Cheever by John Cheever 2010: Tinkers by Paul Harding 1978: Elbow Room by James Alan McPherson 2009: Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 1977: No award given 2008: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 1976: Humboldt's Gift by Saul Bellow 2007: The Road by Cormac McCarthy 1975: The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara 2006: March by Geraldine Brooks 1974: No award given 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson 1973: The Optimist's Daughter by Eudora Welty 2004: The Known World by Edward P. -

The Impact of Trauma on Vietnamese Refugees in Robert Olen Butler's a Good Scent from a Strange Mountain (1992) and Viet Thanh

مجلة كلية اﻵداب للغويات والثقافات المقارنة مج 12، ع1 )يناير(2020 The Impact of Trauma on Vietnamese Refugees in Robert Olen Butler’s A Good Scent from A Strange Mountain (1992) and Viet Thanh Nguyen The Refugees (2017) By Dr. Sherine Abdelghafar [email protected] ABSTRACT After the collapse of the South Vietnamese government, thousands of people fled away from their own country. Eventually, by the late 1980s and early 1990s, many individuals made their way to the United States in order to escape intolerable conditions in their countries and to seek a better life. There were three waves of Vietnamese immigration; the most significant and complicated was the third wave, which came after 1982; it included different types of Vietnamese refugees. This paper attempts to study the challenges Vietnamese refugees have faced in the U.S. Selected stories from the collections of A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain (1992) by Robert Olen Butler, and The Refugees (2017) by Viet Thanh Nguyen, will be studied in the light of the refugee trauma theory. The Vietnam War was a unique war in history and, thus, called for an equally distinctive representation in literature. The stories, in both collections, are connected by the common experience of characters that have survived the war in Vietnam and found their way to America. Both writers offer a diverse group of characters—some protagonists are Vietnamese, others are American, but most are Vietnamese-American. Through the different stories of their characters, Butler and Nguyen explore questions of identity. They focus on how it feels and what it means to be a refugee. -

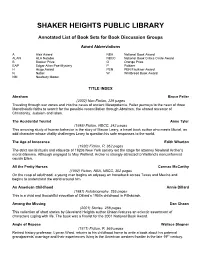

An Annotated Listing of Book Sets

SHAKER HEIGHTS PUBLIC LIBRARY Annotated List of Book Sets for Book Discussion Groups Award Abbreviations A Alex Award NBA National Book Award ALAN ALA Notable NBCC National Book Critics Circle Award B Booker Prize O Orange Prize EAP Edgar Allan Poe-Mystery P Pulitzer H Hugo Award PEN PEN/Faulkner Award N Nobel W Whitbread Book Award NM Newbery Medal TITLE INDEX Abraham Bruce Feiler (2002) Non-Fiction, 229 pages Traveling through war zones and into the caves of ancient Mesopotamia, Feiler journeys to the heart of three Monotheistic faiths to search for the possible reconciliation through Abraham, the shared ancestor of Christianity, Judaism and Islam. The Accidental Tourist Anne Tyler (1985) Fiction, NBCC, 342 pages This amusing study of human behavior is the story of Macon Leary, a travel book author who meets Muriel, an odd character whose vitality challenges Leary to question his safe responses to the world. The Age of Innocence Edith Wharton (1920) Fiction, P, 362 pages The strict social rituals and etiquette of 1920s New York society set the stage for attorney Newland Archer’s moral dilemma. Although engaged to May Welland, Archer is strongly attracted to Welland’s nonconformist cousin Ellen. All the Pretty Horses Cormac McCarthy (1992) Fiction, NBA, NBCC, 302 pages On the cusp of adulthood, a young man begins an odyssey on horseback across Texas and Mexico and begins to understand the world around him. An American Childhood Annie Dillard (1987) Autobiography, 255 pages This is a vivid and thoughtful evocation of Dillard’s 1950s childhood in Pittsburgh. Among the Missing Dan Chaon (2001) Stories, 258 pages This collection of short stories by Cleveland Heights author Chaon features an eclectic assortment of characters coping with life. -

AUTUMN 2013 2 0 1 3 • 1 a Career and a Passion the Writing Life of Adam Johnson, FSU Alumnus and Winner of the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

Across the AUTUMN THETHE FLORIDA FLORIDA STATE STATE UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY COLLEGE COLLEGE OF OF ARTS ARTS AND AND SCIENCES SCIENCES 2 0 1 3 Spectrum New Frontiers Pushing boundaries—on campus and around the world artsandsciences.fsu.edu AUTUMN 2 0 1 3 • 1 Letter from the dean elcome to another edition of Across the Spectrum. As the fall 2013 academic year kicked off, the College of Arts Sciences found itself serving record numbers of students. At the same time there was a welcome expansion in the faculty ranks, owing to the hiring of 25 new faculty members. In this issue, we celebrate our college’s growth, not only in size, but in the depth and breadth of our research, our educational offerings, and our global Photo by FSU Photo Lab Photo FSU by Photo W impact. DEAN PUBLISHER Several of our new faculty hires will spend time at the MagLab, which has become a crown jewel for FSU Sam Huckaba Nancy Smilowitz over the last 20 years. In this issue you will read about its history and get a sense of why scientists flock to EDITOR DESIGNER Tallahassee from all over the world to do research that literally cannot be done anywhere else. Physicist and Wil Oakes Martin Young MagLab director Greg Boebinger explains why magnetic field environments are so important to modern www.oakescreative.com [email protected] research projects ranging from materials science to medicine. PHOTOGRAPHY COPY EDITOR One great benefit of having the MagLab at FSU is that it attracts world-class faculty members—such as Tamara Beckwith Barry Ray Alan Marshall Lawton Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry Alan Marshall. -

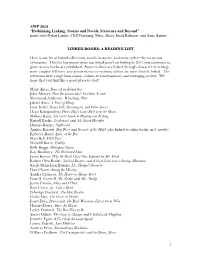

Linked Collections, Novels in Stories, and Story Cycles—By No Means Exhaustive

AWP 2014 “Rethinking Linking: Stories and Novels, Structure and Beyond” panel with Dylan Landis, Cliff Garstang, Mary Akers, Imad Rahman, and Anne Sanow LINKED BOOKS: A READING LIST Here is our list of linked collections, novels in stories, and story cycles—by no means exhaustive. This list has grown since our initial panel on linking in 2011 and continues to grow as new books are published. Some of these are linked through character or setting; some employ full story arcs across stories or sections; others are more loosely linked. The selections here range from classic authors to contemporary and emerging writers. We hope that you find this a good place to start! Mary Akers, Bones of an Inland Sea Julia Alvarez, How the Garcia Girls Lost their Accents Sherwood Anderson, Winesburg, Ohio Jabari Asim, A Taste of Honey Issac Babel, Benya Krik, the Gangster, and Other Stories Dean Bakopoulous, Please Don’t Come Back from the Moon Melissa Bank, The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing Russell Banks, Trailerpark and The Sweet Hereafter Djuana Barnes, Nightwood Andrea Barrett, Ship Fever and Servants of the Map* (also linked to other books, incl. novels) Rebecca Barry, Later, at the Bar Matt Bell, Wolf Parts Wendell Berry, Fidelity Belle Boggs, Mattaponi Queen Ray Bradbury, The Illustrated Man Jason Brown, Why the Devil Chose New England for His Work Robert Olen Butler, Tabloid Dreams and A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum, Ms. Hempel Chronicles Dan Chaon, Among the Missing Sandra Cisneros, The House on Mango Street Evan S. Connell, Mr. -

My Subway Ride Jacket

1 9 m m S p i 6” Front Panel 4.5” Rear Flap 6” Rear Panel n 4.5” Front Flap e Uncorrected galley proof $14.95 U.S.U.S. S Margaret Bishop received a BA from Wesleyan Single Scene Short Stories includes works by the following: I University and an MFA from George Mason University. N She lives and writes in northern Virginia. Single Scene John Barth Jack London G SINGLE SCENE Short Stories is her first book. Jorge Luis Borges Katherine Mansfield L T. Coraghessan Boyle Guy de Maupassant E Short Stories Fred Busch Lorrie Moore Edited by Margaret Bishop Robert Olen Butler Joyce Carol Oates S C Ron Carlson Dorothy Parker E Raymond Carver Grace Paley N Michael Chabon Katherine Anne Porter What is a single scene short story? It is a short work of E Anton Chekhov Mary Robison fiction with a specific remarkable quality—the whole of Colette James Salter S the story takes place in one scene, one geographical coor- Ernest Hemingway John Updike H dinate, one window of time. To think of it dramatically, it O Amy Hempel William Carlos Williams is a story presented on a stage with no change of setting 9 ” H James Joyce Tobias Wolff R or costume, no voice-over summarizing or carrying the e i g h Doris Lessing T viewer from here to there. This collection contains some t of the best single scene short stories ever written, the S modern classics of the form. T Single Scene Short Stories includes the works of such O well-known writers as Michael Chabon, Anton Chekhov, R Raymond Carver, Mary Gaitskill, Ernest Hemingway, I E James Joyce, Guy de Maupassant, Joyce Carol Oates, S Flannery O’Connor, Dorothy Parker, Katherine Anne Porter, John Updike, William Carlos Williams, Tobias SINGLE SCENE Wolff, and many others. -

American Short Stories Since 1945

SUB G6ttingen 213 585 057' 2001 A 13372 AMERICAN SHORT STORIES SINCE 1945 John G. Parks Miami University of Ohio New York Oxford OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS . 2002 CONTENTS Preface ix Introduction 1 1945—1960: The Strains of Accommodation and Consensus SHIRLEY JACKSON (1919-1965) 9 "The Lottery" 9 EUDORAWELTY(i9o9- ) 15 "Why I Live at the P.O." 16 ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER (1904-1991) 25 "The Spinoza of Market Street" 25 TILLIE OLSEN (1913- ) 36 "I Stand Here Ironing" 37 RALPH ELLISON (1914-1994) 42 "Battle Royal" 43 GRACE PALEY (1922- ) 53 "An Interest in Life" 53 J. F. POWERS (1917-1999) 63 "Prince of Darkness" 64 JAMES PURDY (1923- ) 90 "Don't Call Me by My Right Name" 91 BERNARD MALAMUD (1914-1986) 96 "The Jewbird" 96 PETER TAYLOR (1917-1994) 103 "The Old Forest" 103 iv / Contents FLANNERY O'CONNOR (1925-1964) 138 "A Good Man Is Hard to Find" 13 8 "Revelation" 149 WRIGHT MORRIS (1910-1998) 163 "The Ram in the Thicket" 163 JOHN CHEEVER (1912-1982) 174 "The Country Husband" 17 5 "The Housebreaker of Shady Hill" 191 PHILIP ROTH (1933- ) 204 "Defender of the Faith" 205 JAMES BALDWIN (1924-1987) 225 "Sonny's Blues" 226 HISAYE YAMAMOTO (1921- ) 246 "Seventeen Syllables" 247 2. 1960s and 1970s: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs SAUL BELLOW (1915- ) 259 "Looking for Mr. Green" 260 WILLIAM H. GASS (1924- ) 274 "In the Heart of the Heart of the Country" 274 ERNEST J. GAINES (1933- ) 292 "The Sky Is Gray" 292 ROBERT COOVER (1932- ) 312 "The Babysitter" 312 JOHN BARTH (1930- ) 332 "Night-Sea Journey" 333 DONALD BARTHELME (1931-1989) 338 "Views of My Father Weeping" 339 URSULA K.