Apr–Jun 2013 Cinémathèque Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

• Part of a Mixed-Use Development Guoco Midtown That Comprises

Part of a mixed-use development Guoco Midtown that comprises premium Grade A office space, public and retail spaces, exclusive residences, and the former Beach Road Police Station, a conserved building Located within Central Business District, at the intersection of two key development corridors along Beach Road and Ophir-Rochor Road Key connector between 3 office micromarkets – City Hall, Marina Centre & Bugis Served by four MRT lines and Nicoll Highway, as well as the North-South Expressway in the future It will rejuvenate the Beach Road by being the final critical piece of jigsaw that completes the transformation of the precinct It will redefine the leasing concept for Grade A office It will foster community street life by providing a series of community spaces that can adapt and cater to different public activities and events It will introduce a new way of luxury city living in response to the growing trend of live, work and socializing As the heart of the development, Midtown Hub will be an exclusive urban social club that incorporates the best of business and leisure, it is a place to connect like-minded people to create opportunities for collaboration, and ideas to thrive PROJECT INFORMATION GUOCO MIDTOWN Project Name Guoco Midtown Project Name (Chinese) 国浩时代城 Type Mixed-Use Development Developer GuocoLand District 7 Address 120, 124, 126, 128, 130 Beach Road Site Area Approx. 226,300 sqft / 21,026.90 sqm Total GFA Approx. 950,600 sqft / 88,313 sqm Plot Ratio 4.2 Land Price S$1.622 billion / S$1,706 psf ppr Total Development Cost S$2.4 billion Tenure of Land Leasehold tenure of 99 years commencing from 2018 Estimated TOP To be completed in 2022 No. -

Kajian Naratif Atas Tema Nasionalisme Dalam Film-Film Usmar Ismail Era 1950-An

KAJIAN NARATIF ATAS TEMA NASIONALISME DALAM FILM-FILM USMAR ISMAIL ERA 1950-AN TESIS PENGKAJIAN SENI untuk memenuhi persyaratan mencapai derajat magister dalam bidang Seni, Minat Utama Videografi Sazkia Noor Anggraini 1320789412 PROGRAM PENCIPTAAN DAN PENGKAJIAN PASCASARJANA INSTITUT SENI INDONESIA YOGYAKARTA 2017 UPT PERPUSTAKAAN ISI YOGYAKARTA UPT PERPUSTAKAAN ISI YOGYAKARTA PERNYATAAN Saya menyatakan bahwa tesis yang saya tulis ini belum pernah diajukan untuk memperoleh gelar akademik di suatu perguruan tinggi manapun. Tesis ini merupakan hasil pengkajian/penelitian yang didukung berbagai referensi dan sepengetahuan saya belum pernah ditulis dan dipublikasikan kecuali yang secara tertulis diacu dan disebutkan dalam kepustakaan. Saya bertanggungjawab atas keaslian tesis ini dan saya bersedia menerima sanksi apabila di kemudian hari ditemukan hal-hal yang tidak sesuai dengan isi pernyataan ini. Yogyakarta, 10 Agustus 2017 Yang membuat pernyataan, Sazkia Noor Anggraini NIM. 1320789412 iii UPT PERPUSTAKAAN ISI YOGYAKARTA KAJIAN NARATIF ATAS TEMA NASIONALISME DALAM FILM-FILM USMAR ISMAIL ERA 1950-AN Pertanggungjawaban Tertulis Program Penciptaan dan Pengkajian Seni Pascasarjana Institut Seni Indonesia Yogyakarta, 2017 Oleh Sazkia Noor Anggraini ABSTRAK Penelitian ini berangkat dari klaim bahwa film-film sebelum Darah dan Doa (1950) tidak didasari oleh sebuah kesadaran nasional dan oleh karenanya tidak bisa disebut sebagai film Indonesia. Klaim ini perlu dipertanyakan karena punya tendensi akan pengertian sempit etno nasionalis yang keluar dari elite budaya Indonesia. Penelitian ini mencoba membangun argumen secara kritis dengan memeriksa kembali proyeksi tema nasionalisme dalam naratif film-film Usmar Ismail pada era 1950-an. Gagasan nasionalisme kebangsaan oleh Benedict Anderson digunakan sebagai konsep kerja utama dalam membedah naratif pada film Darah dan Doa, Lewat Djam Malam (1954), dan Tamu Agung (1955). -

FITTING-OUT MANUAL for Commercial Occupiers

FITTING-OUT MANUAL for Commercial Occupiers SMRT PROPERTIES SMRT Investments Pte Ltd 251 North Bridge Road Singapore 179102 Tel : 65 6331 1000 Fax : 65 6337 5110 www.smrt.com.sg While every reasonable care has been taken to provide the information in this Fitting-Out Manual, we make no representation whatsoever on the accuracy of the information contained which is subject to change without prior notice. We reserve the right to make amendments to this Fitting-Out Manual from time to time as necessary. We accept no responsibility and/or liability whatsoever for any reliance on the information herein and/or damage howsoever occasioned. 09/2013 (Ver 3.9) Fitting Out Manual SMRT Properties To our Valued Customer, a warm welcome to you! This Fitting-Out Manual is specially prepared for you, our Valued Customer, to provide general guidelines for you, your appointed consultants and contractors when fitting-out your premises at any of our Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) or Light Rail Transit (LRT) stations. This Fitting-Out Manual serves as a guide only. Your proposed plans and works will be subjected to the approval of SMRT and the relevant authorities. We strongly encourage you to read this document before you plan your fitting-out works. Do share this document with your consultants and contractors. While reasonable care has been taken to prepare this Fitting-Out Manual, we reserve the right to amend its contents from time to time without prior notice. If you have any questions, please feel free to approach any of our Management staff. We will be pleased to assist you. -

Yamato Transport Branch Postal Code Address TA-Q-BIN Lockers

Yamato Transport Branch Postal Code Address TA-Q-BIN Lockers Location Postal Code Cheers Store Address Opening Hours Headquarters 119936 61 Alexandra Terrace #05-08 Harbour Link Complex Cheers @ AMK Hub 569933 No. 53 Ang Mo Kio Ave 3 #01-37, AMK Hub 24 hours TA-Q-BIN Branch Close on Fri and Sat Night 119937 63 Alexandra Terrace #04-01 Harbour Link Complex Cheers @ CPF Building 068897 79 Robinson Road CPF Building #01-02 (Parcel Collection) from 11pm to 7am TA-Q-BIN Call Centre 119936 61 Alexandra Terrace #05-08 Harbour Link Complex Cheers @ Toa Payoh Lorong 1 310109 Block 109 #01-310 Toa Payoh Lorong 1 24 hours Takashimaya Shopping Centre,391 Orchard Rd, #B2-201/8B Fairpricexpress Satellite Office 238873 Operation Hour: 10.00am - 9.30pm every day 228149 1 Sophia Road #01-18, Peace Centre 24 hours @ Peace Centre (Subject to Takashimaya operating hours) Cheers @ Seng Kang Air Freight Office 819834 7 Airline Rd #01-14/15, Cargo Agent Building E 546673 211 Punggol Road 24 hours ESSO Station Fairpricexpress Sea Freight Office 099447 Blk 511 Kampong Bahru Rd #02-05, Keppel Distripark @ Toa Payoh Lorong 2 ESSO 319640 399 Toa Payoh Lorong 2 24 hours Station Fairpricexpress @ Woodlands Logistics & Warehouse 119937 63 Alexandra Terrace #04-01 Harbour Link Complex 739066 50 Woodlands Avenue 1 24 hours Ave 1 ESSO Station Removal Office 119937 63 Alexandra Terrace #04-01 Harbour Link Complex Cheers @ Concourse Skyline 199600 302 Beach Road #01-01 Concourse Skyline 24 hours Cheers @ 810 Hougang Central 530810 BLK 810 Hougang Central #01-214 24 hours -

16 March 2015 I Singapore Art Museum Presents the Fifth

Media Release For Immediate Release Singapore Art Museum Presents the Fifth Southeast Asian Film Festival Celebrating the diversity of Southeast Asia through independent cinema Singapore, 16 March 2015 - The fifth edition of the Southeast Asian Film Festival (SEAFF) presented by the Singapore Art Museum (SAM) returns from 10 April to 3 May 2015 with an exciting line-up of the newest and most compelling cinematic work from the region. Celebrating the spirit of independent filmmaking in Southeast Asia and reflecting the region’s diversity, the Festival features films from Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. Taking a co-curated approach, SAM once again collaborates with independent film curators Philip Cheah and Teo Swee Leng for this edition’s film selection, presenting a total of 20 films. The films Chasing Waves (2015) and Fundamentally Happy (2015) make their world premieres at this Festival, while K’na the Dreamweaver (2014) and Riddles of My Homecoming (2013) and Sparks (2014) are international premieres showing outside their home countries for the first time. Opening and Closing Films SEAFF opens with the film The Last Executioner (2014), directed by Tom Waller, which tells the story of Chavoret Jarubon - the last person in Thailand whose job was to execute death row prisoners with a machine gun. The film stars Vithaya Pansringarm in the role of Chavoret, for which he won Best Actor at the Shanghai Film Festival in 2014. He is also internationally known for his role in the 2013 crime drama Only God Forgives alongside Ryan Gosling and Kirsten Scott Thomas. The closing film, NOVA (2014) by Malaysian director Nik Amir Mustapha, is a tale about the madcap adventure of a group of friends on a quest to prove that UFOs are real. -

Where Everything Meets in the Middle

WHERE EVERYTHING MEETS IN THE MIDDLE Development Information Located in Middle Road, this is a 99-year leasehold mixed-use development with 522 residential apartments and one level of retail component. The site has a land area of 7,462.7 sq m and a permissible gross floor area of 31,344 sq m. The M consists of three 20-storey towers and one 6-storey tower. CONFIDENTIAL STRICTLY FOR INTERNAL USE ONLY & NOT FOR CIRCULATION SUBJECT TO CHANGE 10 Jan 2020 The development is in Bugis, right in the heart of the Arts and Cultural District and next to the Civic District. It has excellent connectivity with well-established transportation network and will eventually transform into one of the car-lite district of the nation, in accordance to the plans of the authority. It is walking distance to 3 MRT stations (4 min walk to Bugis MRT station, 6 min walk to City Hall MRT station and 8 min walk to Esplanade MRT station). The Central Business District and The Marina Bay Financial District is 2 and 3 MRT stations away respectively. The Orchard Road shopping belt is also just minutes’ away. The residents of the M will also benefit from the wide range of amenities and F&B options round the clock at Bugis and City Hall. Information at a Glance Project Name: The M Address: 30, 32, 34, 36, 38 Middle Road Postal Code: 188940, 188941, 188943, 188945, 188947 District: 7 Developer: Wingcharm Investment Pte Ltd, a subsidiary of Wing Tai Asia Tenure: 99-year leasehold Land Area: Approx. -

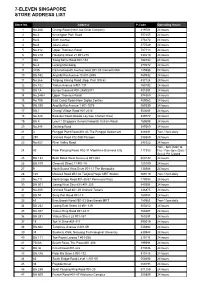

SLIDE Store Listing- 1 Apr 2019

7-ELEVEN SINGAPORE STORE ADDRESS LIST Store No. Address P.Code Operating Hours 1 No.38A Changi Road (Near Joo Chiat Complex) 419701 24 hours 2 No.3 Kensington Park Road 557255 24 hours 3 No.6 Sixth Avenue 276472 24 hours 4 No.6 Jalan Leban 577549 24 hours 5 No.912 Upper Thomson Road 787113 24 hours 6 Blk.210 Hougang Street 21 #01-275 530210 24 hours 7 302 Tiong Bahru Road #01-152 168732 24 hours 8 No.4 Lorong Mambong 277672 24 hours 9 3155 Commonwealth Avenue West #01-03 Clementi Mall 129588 24 hours 10 Blk.532 Ang Mo Kio Avenue 10 #01-2455 560532 24 hours 11 No.366 Tanjong Katong Road (Opp. Post Office) 437124 24 hours 12 Blk.102 Yishun Avenue 5 #01-137 760102 24 hours 13 Blk.1A Eunos Crescent #01-2469/2471 401001 24 hours 14 No.244H Upper Thomson Road 574369 24 hours 15 No.705 East Coast Road (Near Siglap Centre) 459062 24 hours 16 Blk.339 Ang Mo Kio Avenue 1 #01-1579 560339 24 hours 17 Blk.1 Changi Village Road #01-2014 500001 24 hours 18 No.340 Balestier Road (beside Loy Kee Chicken Rice) 329772 24 hours 19 Blk 4 Level 1 Singapore General Hospital Outram Road 169608 24 hours 20 No.348 Geylang Road 389369 24 hours 21 3 Punggol Point Road #01-06 The Punggol Settlement 828694 7am-11pm daily 22 290 Orchard Road #02-08B Paragon 238859 24 hours 23 No.423 River Valley Road 248322 24 hours 7am - 8pm (Mon to 24 40 Pasir Panjang Road, #02-31 Mapletree Business City 117383 Fri) / 7am-3pm (Sat) / Sun & PH Closed 25 Blk.132 Bukit Batok West Avenue 6 #01-304 650132 24 hours 26 Blk.109 Clementi Street 11 #01-15 120109 24 hours 27 9 North Buona Vista -

Q&A PROGRAM KINEFORUM MARET 2011 SEJARAH ADALAH SEKARANG 5 Page 1

Q&A PROGRAM KINEFORUM MARET 2011 SEJARAH ADALAH SEKARANG 5 SENIN SELASA RABU KAMIS JUMAT SABTU MINGGU 1 2 3 4 5 6 WARNA WARNI BUKAN SEKEDAR BOW: USMAR ISMAIL FESTIVAL 80-AN FILM ANAK INDONESIA FILM ANAK INDONESIA PEREMPUAN PROFESI BOW: USMAR ISMAIL GAMBAR TANGAN, LAYAR GAMBAR TANGAN, LAYAR TEREKAM, TERDENGAR, TEREKAM, TERDENGAR, PERAN PEMERAN LEBAR LEBAR TERLIHAT TERLIHAT FESTIVAL 80-AN WARNA WARNI PERAN PEMERAN GAMBAR TANGAN, LAYAR PEREMPUAN LEBAR kineforum 14.15: Perempuan Kedua 14.15: Raja Jin Penjaga 14.15: Red Cobex 14.15: Ira Maya Putri 14.15: Langitku, Rumahku 14.15: Djenderal Kantjil Pintu Kereta Api Cinderella 17.00: Darah dan Doa 17.00: Badut-badut Kota 17.00: Enam Djam di 17.00: Metamorfoblus 17.00: The Songstress and 17.00: Petualangan Sherina Djogdja the Seagull 19.30: Nakalnya Anak-anak 19.30: Sorga yang Hilang 19.30: Beranak Dalam 19.30: Kejarlah Daku, Kau 19.30: Tuan Tanah 19.30: Fiksi Kubur Kutangkap Kedawung 16:00 Diskusi Dari Gambar Acara Pendukung Tangan ke Layar Lebar GC III Pameran Sejarah Bioskop Pameran Sejarah Bioskop Pameran Sejarah Bioskop Pameran Sejarah Bioskop Pameran Sejarah Bioskop Pameran Sejarah Bioskop dan Kebijakan Film di dan Kebijakan Film di dan Kebijakan Film di dan Kebijakan Film di dan Kebijakan Film di dan Kebijakan Film di Indonesia Indonesia Indonesia Indonesia Indonesia Indonesia 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 FESTIVAL 80-AN SUPERHERO BUKAN SEKEDAR TEREKAM, TERDENGAR, SUPERHERO FILM ANAK INDONESIA FILM ANAK INDONESIA PROFESI TERLIHAT WARNA WARNI WARNA WARNI GAMBAR TANGAN, LAYAR BOW: USMAR ISMAIL BUKAN -

Singapore for Families Asia Pacificguides™

™ Asia Pacific Guides Singapore for Families A guide to the city's top family attractions and activities Click here to view all our FREE travel eBooks of Singapore, Hong Kong, Macau and Bangkok Introduction Singapore is Southeast Asia's most popular city destination and a great city for families with kids, boasting a wide range of attractions and activities that can be enjoyed by kids and teenagers of all ages. This mini-guide will take you to Singapore's best and most popular family attractions, so you can easily plan your itinerary without having to waste precious holiday time. Index 1. The Singapore River 2 2. The City Centre 3 3. Marina Bay 5 4. Chinatown 7 5. Little India, Kampong Glam (Arab Street) and Bugis 8 6. East Coast 9 7. Changi and Pasir Ris 9 8. Central and North Singapore 10 9. Jurong BirdPark, Chinese Gardens and West Singapore 15 10. Pulau Ubin and the islands of Singapore 18 11. Sentosa, Universal Studios Singapore and "Resorts World" 21 12. Other attractions and activities 25 Rating: = Not bad = Worth trying = A real must try Copyright © 2012 Asia-Pacific Guides Ltd. All rights reserved. 1 Attractions and activities around the Singapore River Name and details What is there to be seen How to get there and what to see next Asian Civilisations Museum As its name suggests, this fantastic Address: 1 Empress Place museum displays the cultures of Asia's Rating: tribes and nations, with emphasis on From Raffles Place MRT Station: Take Exit those groups that actually built the H to Bonham Street and walk to the river Tuesday – Sunday : 9am-7pm (till city-state. -

1 Media Release for Immediate Release SAM Unveils Limited

Media Release For Immediate Release SAM Unveils Limited Edition Merchandise in Conjunction with SG50 Exhibition Created in collaboration with Singaporean designers ALT, Carrie K., SUPERMAMA, SunMoonRain, and Vice & Vanity Singapore, 26 May 2015 – In this jubilee year of the nation’s independence, the Singapore Art Museum celebrates Singapore’s founding values with limited edition merchandise - the 5 Stars Commitment Bands - in conjunction with SAM’s upcoming contemporary art exhibition 5 Stars. Each band in the series is symbolic of one of the five stars on the Singapore national flag, representing justice, progress, democracy, peace, and equality. Created in collaboration with Singaporean designers ALT, Carrie K., SUPERMAMA, SunMoonRain, and Vice & Vanity, the bands will be available for purchase at SUPERMAMA at SAM from 4 September 2015 onwards, with the opening of the 5 Stars exhibition. ALT is an independent accessories label started by Angie Lai-Tay, which seeks to empower women through statement-making designs inspired by architectural and geometrical shapes. Taking on the value of Justice, ALT is working with a Cambodian fair trade organisation to produce its commitment band in a socially responsible and sustainable way, out of brass recycled from discarded bombshells. Established by designer and silversmith Carolyn Kan, Carrie K. creates playfully provocative artisan-crafted jewellery which challenge traditional notions of what is precious and desirable. Carrie K.’s collections started off in silver but now include other materials such as gold, black diamonds and leather. Inspired by Progress, the commitment band will embody the Carrie K. philosophy of handcrafting meaningful and covetable jewellery. The delicate bracelets by SunMoonRain combine modern design with the power of precious and semi-precious stones and crystals that encourage positive energy and healing. -

Tenant's Fitting-Out Manual

FITTING-OUT MANUAL for Commercial (Shops) Tenants The X Collective Pte Ltd 2 Tanjong Katong Road #08-01, Tower 3, Paya Lebar Quarter Singapore 437161 Tel : 65 6331 1333 www.smrt.com.sg While every reasonable care has been taken to provide the information in this Fitting-Out Manual, SMRT makes no representation whatsoever on the accuracy of the information contained which is subject to change without prior notice. SMRT reserves the right to make amendments to this Fitting-Out Manual from time to time as necessary. SMRT accepts no responsibility and/or liability whatsoever for any reliance on the information herein and/or damage howsoever occasioned. 04/2019 (Ver 4.0) 1 Contents FOREWORD ………..…………….……….……………………………...………………… 4 GENERAL INFORMATION ………………………………………………………………… 5 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS / DEFINITIONS ………………..................................... 6 1. OVERVIEW ….……………..…………………………….…………………..…… 7 2. FIT-OUT PROCEDURES ……………………………..………………..…..…... 8 2.1. Stage 1 – Introductory and Pre Fit-Out Briefing …….…………………………… 8 2.2. Stage 2 – Submission of Fit-Out Proposal for Preliminary Review …….…… 8 2.3. Stage 3 – Resubmission of Fit-Out Proposal After Preliminary Review …........11 2.4. Stage 4 – Site Possession …..……………………………………..…….……….. 11 2.5. Stage 5 – Fitting-Out Work ………………………………………………..………. 12 2.6. Stage 6 – Post Fit-Out Inspection and Submission of As-Built Drawings….. 14 3. TENANCY DESIGN CRITERIA & GUIDELINES …..……………..……………. 15 3.1 Design Criteria for Shop Components ……….………………………….….…… 15 3.2 Food & Beverage Units (Including Cafes and Restaurants) ………..……..….. 24 3.3 Design Control Area (DCA) …………………………………………..……..……. 26 4. FITTING-OUT CONTRACTOR GUIDELINES …..……………………………. 27 4.1 Building and Structural Works …………………………………………..……. 27 4.2 Mechanical and Electrical Services ….………………………………….…. 28 4.3 Public Address (PA) System ……….……………………………………….. 39 4.4 Sub-Directory Signage ……..…………………………………………………. -

Bab 2 Sekilas Perkembangan Perfilman Di Indonesia 2.1

BAB 2 SEKILAS PERKEMBANGAN PERFILMAN DI INDONESIA 2.1 Awal Perkenalan Awalnya masyarakat Hindia Belanda pada tahun 1900 mengenal film yang sekarang kita kenal dengan sebutan gambar idoep. Istilah gambar idoep mulai dikenal saat surat kabar Bintang Betawi memuat iklan tentang pertunjukan itu. Iklan dari De Nederlandsche Bioscope Maatschappij di surat kabar Bintang Betawi menyatakan: “...bahoewa lagi sedikit hari ija nanti kasi lihat tontonan amat bagoes jaitoe gambar-gambar idoep dari banyak hal..”22 Selanjutnya pada tanggal 4 Desember surat kabar itu kembali mengeluarkan iklan yang berbunyi: “...besok hari rabo 5 Desember PERTOENJOEKAN BESAR JANG PERTAMA di dalam satoe roemah di Tanah Abang Kebondjae (MANEGE) moelain poekoel TOEDJOE malem..”23 22 Bintang Betawi. Jum’at, 30 November 1900. Universitas Indonesia Kebijakan pemeerintah..., Wisnu Agung Prayogo, FIB UI, 2009 Film yang dipertontonkan saat itu merupakan film dokumenter yang menceritakan tentang perkembangan terakhir pembangunan di Belanda dan Afrika Selatan. Film ini juga menampilkan profil keluarga kerajaan Belanda. Tahun 1910 sendiri tercatat sebagai tahun kegiatan pembuatan film yang lebih bersifat pendokumentasian tentang Hindia Belanda agar ada pengenalan yang lebih “akrab“ antara negeri induk (Belanda) dengan daerah jajahan.24 Industri pembuatan film di wilayah Hindia Belanda sendiri baru dimulai sejak tahun 1926 ketika sebuah film berjudul Loetoeng Kasaroeng dibuat oleh L.Hoeveldorp dari NV Java Film Company pimpinan G. Krugers dan F. Carli.25 Java Film Company kemudian