The Royal Engineers Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Document Is the Interim Report for IDB Contract No

Development of the Industrial Park Model to Improve Trade Opportunities for Haiti – HA-T1074-SN2 FINAL REPORT submitted to September 20, 2010 99 Nagog Hill Road, Acton, Massachusetts 01720 USA Tel: +1-978-263-7738 e-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.koiosllc.com Table of Contents Executive Summary i I. Introduction 1 A. Background and History 1 B. Haiti’s Current Economic Situation 2 C. Purpose and Objectives of this Study 3 II. Overview of Garment Industry Trends 5 A. The Levelling Playing Field 5 B. Competitive Advantages in the Post-MFA World 7 III. Haiti’s Place in the Post-MFA World 11 A. The Structure of Haiti’s Garment Production 11 B. The Way Forward for Hait’s Garment Industry 14 1. Trade Preference Levels 14 2. How Will Haiti Fit Into Global Supply Chains? 22 3. Beyond HELP 24 C. The Competitive Case for Haiti and the North 27 1. A New Vision for Haiti – Moving on from CMT 27 2. Why the North? 30 D. Garment Manufacturers’ Requirements in North Haiti 32 1. Land 32 2. Pre-built Factory Sheds 33 3. Water and Water Treatment 34 4. Electricity 36 5. Road Transport 37 6. Business Facilitation and Services 37 E. Park Development Guidelines 37 IV. Site Identification, Evaluation, and Selection 43 A. Site Selection Factors and Methodology 43 B. Site Selection 47 1. Regional Context Summary 47 2. Infrastructure Constraints 48 3. Evaluation and Selection Process 50 4. Site Selection Methodology 52 5. Site Ranking and Descriptions 54 C. Development Costs 59 1. -

The Evolution of Personal Pledging for the Freemen of Norwich, 1365-1441

Quidditas Volume 39 Article 6 2018 The Evolution of Personal Pledging for the Freemen of Norwich, 1365-1441 Ruth H. Frost University of British Columbia Okanagan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Frost, Ruth H. (2018) "The Evolution of Personal Pledging for the Freemen of Norwich, 1365-1441," Quidditas: Vol. 39 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol39/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Quidditas 39 94 The Evolution of Personal Pledging for the Freemen of Norwich, 1365-1441 Ruth H. Frost University of British Columbia Okanagan This paper examines the evolution of the personal pledging system used by newly admitted freemen, or citizens, of Norwich between 1365 and 1441. It argues that in the late fourteenth century new freemen chose their own sureties, and a large, diverse body of men acted as their pledges. The personal pledging system changed early in the fifteenth century, however, and from 1420 to 1441 civic office holders, particularly the sheriffs, served as the vast majority of pledges. This alteration to the pledging system coincided with changes to the structure and composition of Norwich’s government, and it paralleled a decrease in opportunities for the majority of Norwich’s freemen to participate in civic government.1 On September 14, 1365, thirteen men came before Norwich’s assembly and swore their oaths as new freemen of the city.2 They promised to pay entrance fees ranging from 13s. -

Wales and Slavery-2007

A Wales Office Publication Wales and SLAVERY Marking 200 years since the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act Foreword The Slave Compensation Commission here can be few episodes in the history of the world that Thave been more shameful or inhuman than the The Wales Office has its own direct historic link with the abolition transatlantic slave trade. of the slave trade. Gwydyr House – home to the Wales Office in Whitehall, London Wales was part of this: Welsh men and women made large – was used to accommodate the Slave Compensation Commission profits from slavery. Equally people from Wales fought hard for for part of its life in the 19th Century. its abolition, with 1807 marking the beginning of the long road to the eventual abolition of slavery within the former British The Commission was one of the more controversial outcomes Empire by 1833. of the abolition of slavery. It was established in 1833 following the decision by the British Government to set aside £20 million Today, it is difficult to understand how this appalling crime to compensate planters, slave traders and slave owners for the against humanity - fuelled by racism and greed - was ever abolition. Today that figure would equate to £2billion. Nothing acceptable, let alone legal. But what is even harder to was ever awarded to a former slave. comprehend is that, although slavery was finally legally abolished after a long struggle in the Americas in 1888, it still continues in practice today. Over 20 million people across the world are estimated still to be suffering in the miserable daily reality of slavery and servitude. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Court of Common Council, 05/03

Public Document Pack PLEASE BRING THIS AGENDA WITH YOU 1 The Lord Mayor will take the Chair at ONE of the clock in the afternoon precisely. COMMON COUNCIL SIR/MADAM, You are desired to be at a Court of Common Council, at GUILDHALL, on THURSDAY next, the 5th day of March, 2020. JOHN BARRADELL, Town Clerk & Chief Executive. Guildhall, Wednesday 26th February 2020 Vincent Thomas Keaveny Aldermen on the Rota The Rt Hon. the Baroness Patricia Scotland of Asthal, QC 2 1 Apologies 2 Declarations by Members under the Code of Conduct in respect of any items on the agenda 3 Minutes To agree the minutes of the meeting of the Court of Common Council held on 16 January 2020. For Decision (Pages 1 - 16) 4 Resolutions on Retirements, Congratulatory Resolutions, Memorials 5 Mayoral Visits The Right Honourable The Lord Mayor to report on his recent overseas visits. 6 Policy Statement To receive a statement from the Chairman of the Policy and Resources Committee. 7 Docquets for the Hospital Seal 8 The Freedom of the City To consider a circulated list of applications for the Freedom of the City. For Decision (Pages 17 - 22) 9 Legislation To receive a report setting out measures introduced into Parliament which may have an effect on the services provided by the City Corporation. For Information (Pages 23 - 24) 10 Ballot Results The Town Clerk to report the outcome of the ballot taken at the last Court: Where appropriate:- * denotes a Member standing for re-appointment; denotes appointed. Two Members to the Trust for London. -

Freedom, N. : Oxford English Dictionary 2/20/20, 13:15

freedom, n. : Oxford English Dictionary 2/20/20, 13:15 Oxford English Dictionary | The definitive record of the English language freedom, n. Pronunciation: Brit. /ˈfriːdəm/, U.S. /ˈfridəm/ Forms: α. eOE freodoom, eOE friadom, OE freodum (rare), OE freogdom (in a late copy), OE freohdom (rare), OE freowdom (probably transmission error), OE frigedom (rare), OE–eME freodom, OE–eME friodom, lOE frigdom, lOE frydom, lOE–eME fridom, eME friedom, ME ffredam, ME ffredom, ME fredam, ME fredame, ME fredowm, ME fredowme, ME freedam, ME freodam, ME–15 ffredome, ME–16 fredome, ME–16 freedome, ME–18 fredom, ME– freedom, 15–16 freedoom, 15–16 freedoome, 16 ffreedom, 16 ffreedome; Scottish pre-17 freddome, pre-17 fredom, pre-17 fredome, pre-17 fredoum, pre-17 fredoume, pre- 17 fredowm, pre-17 fredowme, pre-17 fredum, pre-17 fredume, pre-17 fredwm, pre-17 fredwme, pre-17 freedome, pre-17 freidom, pre-17 freidome, pre-17 fridome, pre-17 friedom, pre-17 friedome, pre-17 17– freedom. β. southern ME uridom, ME vridom. Frequency (in current use): Origin: A word inherited from Germanic. Etymons: FREE adj., -DOM suffix. Etymology: Cognate with or formed similarly to Old Frisian frīdōm (West Frisian frijdom ), Middle Dutch vrīdoem , vrīdom (Dutch vrijdom , vrijdoom , now rare and archaic), Middle Low German vrīdōm , Old High German frītuom (Middle High German vrītuom ) < the Germanic base of FREE adj. + the Germanic base of -DOM suffix. Compare also Old Frisian frīhēd (West Frisian frijheid ), Middle Dutch vrīheid (Dutch vrijheid ), Middle Low German vrīhēt , vrīheit ( > Old Swedish frihet (Swedish frihet )), Old High German frīheit (Middle High German vrīheit , German Freiheit ), and the Germanic forms cited at FRELS v. -

Aware: Royal Academy of the Arts Art Fashion Identity

London College of Fashion Aware: Royal Academy of the Arts Art Fashion Identity International Symposium London College of Fashion is delighted London College of Fashion is committed This two-day symposium is exemplary to be a partner in this exciting and to extending the influence of fashion, of the relationship that the college challenging exhibition, and to be able be it economically, socially or politically, continuously strives to develop between to provide contributions from some of and we explore fashion in many its own internally mandated activities the college’s leading researchers, artists contexts. This exhibition encapsulates and programs with broader discourses and designers. vital characteristics of today’s fashion and practices within the fields of art and education, and it supports my belief that design. With the recent appointment The relationship between art and fashion has the potential to bring about of London College of Fashion Curator, fashion, through conceptual and practical social change when considered in contexts Magdalene Keaney, and significant expression, is at the London College of of identity, individuality, technology and developments to the Fashion Space Fashion’s core. We were immensely proud the environment. Gallery at London College of Fashion to endorse the development of ‘Aware’ we now intend to increase public from its original concept by Lucy Orta, We see this in the work of Professor awareness of how fashion has, is, and London College of Fashion Professor of Helen Storey, whose ‘Wonderland’ project will continue to permeate new territories. Art, Fashion and Environment, together brings together art and science to find real The opportunity to work with the Royal with curator Gabi Scardi. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Court of Aldermen, 11/05/2021 12:30

Public Document Pack COURT OF ALDERMEN SIR/MADAM YOUR Worship is desired to be at a public meeting of the Court of Aldermen on Tuesday next, the 11th day of MAY, 2021. The public meeting will be accessible at: https://youtu.be/J6vJYUjKhqo The Lord Mayor will take the Chair at 12.30 pm of the clock in the afternoon precisely. (if unable to attend please inform the Town Clerk at once.) TIM ROLPH, Swordbearer. Swordbearer’s Office, Mansion House, Tuesday, 4th May 2021 1 Question - That the minutes of the last Courts held on 16 March 2021 and 12 April 2021 are an accurate record? (Pages 7 - 12) 2 Resolutions on Retirements, Congratulatory Resolutions, memorials, etc. 3 The Chamberlain to make the prescribed declaration under the Promissory Oaths Act, 1868 4 Mr Chamberlain's list of Applicants for the Freedom of the City:- Name Occupation Address Company Jenny Louise Adin- an Embroiderer Merstham, Redhill, Broderers Christie Surrey Vikas Aggarwal a Government Southwark International Bankers Accountant Andrew John Lorne a Solicitor and Ealing Arbitrators Aglionby Arbitrator 2 Name Occupation Address Company Philip James Ambler a Policy Consultant Sevenoaks, Kent Spectacle Makers Maria Eugenia Baker a Paper Conservator Chiswick Tin Plate Workers Alias Wire Workers Judith Margaret a Meat Retail Reading, Berkshire Butchers Batchelar, OBE Company Director Benjamin Bayer a Farmer Blandford, Dorset Butchers Nichola Anne Begg a Sales Manager Chippenham, Wiltshire Information Technologists Mark Lafe Berman a Lawyer Golders Green Solicitors Roger Clive -

Savile-Row-Inside-Out.Pdf

Savile Row: Inside Out 1 Savile Row BeSpoke aSSociation he Savile Row Bespoke Association is dedicated to protecting and promoting Tthe practices and traditions that have made Savile Row the acknowledged home of the best bespoke tailoring and a byword for unequalled quality around the world. The SRBA comprises of fifteen member and associate houses, who work together to protect and champion the understanding of bespoke tailoring and to promote the ingenious craftsmen that comprise the community of Savile Row. The SRBA sets the standards that define a Savile Row bespoke tailor, and all members of the Association must conform to the key agreed definitions of a bespoke suit and much more besides. A Master Cutter must oversee the work of every tailor employed by a member house and all garments must be constructed within a one hundred yard radius of Savile Row. Likewise, every member must offer the customer a choice of at least 2,000 cloths and rigorous technical requirements are expected. For example, jacket foreparts must be entirely hand canvassed, buttonholes sewn, sleeves attached and linings felled all by hand. It takes an average 50 plus hours to produce a suit in our Savile Row cutting rooms and workshops. #savilerowbespoke www.savilerowbespoke.com 2 1 Savile Row: inSide out Savile Row: Inside Out looks inside the extraordinary world of bespoke tailoring; an exclusive opportunity to step behind the scenes and celebrate the tailor’s art, the finest cloth and the unequalled expertise that is British Bespoke. A real cutter will be making a real suit in our pop-up cutting room in front of a collection of the work – both ‘before’ and ‘after’ to show the astonishing level of craftsmanship you can expect to find at Savile Row’s leading houses. -

Peterborough City Council on Council Size to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England

AB Submission by Peterborough City Council on Council Size to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England 1. Introduction and Background This document sets out Peterborough City Council’s submission to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) on council size. On 21 May 2012, the LGBCE advised the council that it intended to carry out a Further Electoral Review of the council due to a number of imbalances in the councillor: elector ratios resulting in both over-represented and under-represented areas. In eight of the city’s 24 wards the electoral variance is in excess of 10 per cent from the average for the city as a whole and in one ward (Orton with Hampton), the variance is greater than 30 per cent. This submission has been developed by a cross-party group of councillors and has been agreed at a meeting of the Full Council on 10 July 2013. The submission has been informed by: • Briefings provided by the LGBCE to all councillors, including parish councillors and key officers • Current and projected electorate figures • The work of the cross-party Councillors Electoral Review Group, who met on a number of occasions between March and June 2013 The last Review on the electoral arrangements for Peterborough local authority area was carried out by the Boundary Committee for England (BCFE) and completed in July 2002. The main final recommendations of that review were that: “Peterborough City Council should have 57 councillors, the same as at present; there should be 24 wards, the same as at present.” At the time of that review, the electorate totalled 109,100 (February 2001), and was estimated to grow to 117,990 by 2006. -

London Home of Menswear

LONDON IS THE HOME OF MENSWEAR TEN ICONIC STYLES BRITAIN GAVE THE WORLD TEN ICONIC STYLES BRITAIN GAVE THE WORLD The home of the world’s oldest milliner and the birthplace of THE THREE PIECE SUIT DANDY the brogue shoe; London has evolved into the leading centre of innovation and craftsmanship in men’s fashion. We have given the In October 1666, Charles II introduced a ‘new At the beginning of the 19th century George world the three-piece suit, the trench coat and the bowler hat. fashion’. He adopted a long waistcoat to be worn (Beau) Brummell established a new mode of with a knee-length coat and similar-length shirt. dress for men that observed a sartorial code Since 1666, the areas of Mayfair, Piccadilly and St. James have Samuel Pepys, the son of a tailor recorded in his that advocated a simplified form of tailcoat, a become synonymous with quality, refinement and craftsmanship diary that Charles had adopted ‘a long cassocke linen shirt, an elaborately knotted cravat and full after being colonised by generations of hatters, shoemakers, shirt- close to the body, of black cloth, and pinked with length ‘pantaloons’ rather than knee breeches and makers, jewellers and perfumers. white silk under it, and a coat over it’. This marked stockings. An arbiter of fashion and a close friend the birth of the English suiting tradition and over of the Prince Regent, Brummell had high standards Today the influence of this exclusive enclave of quality menswear time the waistcoat lost its sleeves and got shorter of cleanliness and it is claimed that he took five has spread across London and beyond. -

Freedom by Servitude.Pdf

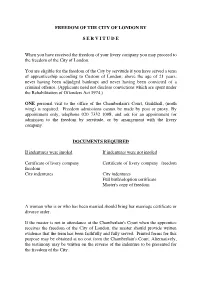

FREEDOM OF THE CITY OF LONDON BY S E R V I T U D E When you have received the freedom of your livery company you may proceed to the freedom of the City of London. You are eligible for the freedom of the City by servitude if you have served a term of apprenticeship according to Custom of London; above the age of 21 years; never having been adjudged bankrupt and never having been convicted of a criminal offence. (Applicants need not disclose convictions which are spent under the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974.) ONE personal visit to the office of the Chamberlain's Court, Guildhall, (north wing) is required. Freedom admissions cannot be made by post or proxy. By appointment only, telephone 020 7332 1008, and ask for an appointment for admission to the freedom by servitude, or by arrangement with the livery company. DOCUMENTS REQUIRED If indentures were inroled If indentures were not inroled Certificate of livery company Certificate of livery company freedom freedom City indentures City indentures Full birth/adoption certificate Master's copy of freedom A woman who is or who has been married should bring her marriage certificate or divorce order. If the master is not in attendance at the Chamberlain's Court when the apprentice receives the freedom of the City of London, the master should provide written evidence that the term has been faithfully and fully served. Printed forms for this purpose may be obtained at no cost from the Chamberlain's Court. Alternatively, the testimony may be written on the reverse of the indenture to be presented for the freedom of the City. -

Branding the Iconic Ideals of Vivienne Westwood, Barack Obama, and Pope Francis

PUNK, OBAMACARE, AND A JESUIT: BRANDING THE ICONIC IDEALS OF VIVIENNE WESTWOOD, BARACK OBAMA, AND POPE FRANCIS AIDAN MOIR A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMMUNICATION & CULTURE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO April 2021 © Aidan Moir, 2021 Abstract Practices of branding, promotion, and persona have become dominant influences structuring identity formation in popular culture. Creating an iconic brand identity is now an essential practice required for politicians, celebrities, global leaders, and other public figures to establish their image within a competitive media landscape shaped by consumer society. This dissertation analyzes the construction and circulation of Vivienne Westwood, Barack Obama, and Pope Francis as iconic brand identities in contemporary media and consumer culture. The content analysis and close textual analysis of select media coverage and other relevant material on key moments, events, and cultural texts associated with each figure deconstructs the media representation of Westwood, Obama, and Pope Francis. The brand identities of Westwood, Pope Francis, and Obama ultimately exhibit a unique form of iconic symbolic power, and exploring the complex dynamics shaping their public image demonstrates how they have achieved and maintained positions of authority. Although Westwood, Obama, and Pope Francis initially were each positioned as outsiders to the institutions of fashion, politics, and religion that they now represent, the media played a key role in mainstreaming their image for public consumption. Their iconic brand identities symbolize the influence of consumption in shaping how issues of public good circulate within public discourse, particularly in regard to the economy, health care, social inequality, and the environment.