Education for Reconciliation Métis Professional Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 4-I: Descriptions of the Life Stages and Habitat Requirements For

APPENDIX 4-I DESCRIPTIONS OF THE LIFE STAGES AND HABITAT REQUIREMENTS FOR FISH AND FISH HABITAT KEY INDICATOR RESOURCES MEG Energy Corp. - i - Fish and Fish Habitat KIRs Christina Lake Regional Project – Phase 3 Appendix 4-I April 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE 1 INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................1 1.1 ARCTIC GRAYLING........................................................................................................2 1.2 NORTHERN PIKE ...........................................................................................................3 1.3 WALLEYE........................................................................................................................4 1.4 WHITE SUCKER .............................................................................................................6 1.5 BROOK STICKLEBACK..................................................................................................7 1.6 BENTHIC INVERTEBRATES..........................................................................................7 2 REFERENCES..........................................................................................................9 2.1 PERSONAL COMMUNICATIONS ................................................................................11 LIST OF TABLES Table 1 Fish Life Cycle Stages and Habitat Components............................................................1 Volume 4 MEG Energy Corp. - 1 - Fish and Fish Habitat KIRs Christina -

Francophone Historical Context Framework PDF

Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Canot du nord on the Fraser River. (www.dchp.ca); Fort Victoria c.1860. (City of Victoria); Fort St. James National Historic Site. (pc.gc.ca); Troupe de danse traditionnelle Les Cornouillers. (www. ffcb.ca) September 2019 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Table of Contents Historical Context Thematic Framework . 3 Theme 1: Early Francophone Presence in British Columbia 7 Theme 2: Francophone Communities in B.C. 14 Theme 3: Contributing to B.C.’s Economy . 21 Theme 4: Francophones and Governance in B.C. 29 Theme 5: Francophone History, Language and Community 36 Theme 6: Embracing Francophone Culture . 43 In Closing . 49 Sources . 50 2 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework - cb.com) - Simon Fraser et ses Voya ses et Fraser Simon (tourisme geurs. Historical contexts: Francophone Historic Places • Identify and explain the major themes, factors and processes Historical Context Thematic Framework that have influenced the history of an area, community or Introduction culture British Columbia is home to the fourth largest Francophone community • Provide a framework to in Canada, with approximately 70,000 Francophones with French as investigate and identify historic their first language. This includes places of origin such as France, places Québec, many African countries, Belgium, Switzerland, and many others, along with 300,000 Francophiles for whom French is not their 1 first language. The Francophone community of B.C. is culturally diverse and is more or less evenly spread across the province. Both Francophone and French immersion school programs are extremely popular, yet another indicator of the vitality of the language and culture on the Canadian 2 West Coast. -

NB4 - Rivers, Creeks and Streams Waterbody Waterbody Detail Season Bait WALL NRPK YLPR LKWH BURB GOLD MNWH L = Bait Allowed Athabasca River Mainstem OPEN APR

Legend: As examples, ‘3 over 63 cm’ indicates a possession and size limit of ‘3 fish each over 63 cm’ or ‘10 fish’ indicates a possession limit of 10 for that species of any size. An empty cell indicates the species is not likely present at that waterbody; however, if caught the default regulations for the Watershed Unit apply. SHL=Special Harvest Licence, BKTR = Brook Trout, BNTR=Brown Trout, BURB = Burbot, CISC = Cisco, CTTR = Cutthroat Trout, DLVR = Dolly Varden, GOLD = Goldeye, LKTR = Lake Trout, LKWH = Lake Whitefish, MNWH = Mountain Whitefish, NRPK = Northern Pike, RNTR = Rainbow Trout, SAUG = Sauger, TGTR = Tiger Trout, WALL = Walleye, YLPR = Yellow Perch. Regulation changes are highlighted blue. Waterbodies closed to angling are highlighted grey. NB4 - Rivers, Creeks and Streams Waterbody Waterbody Detail Season Bait WALL NRPK YLPR LKWH BURB GOLD MNWH l = Bait allowed Athabasca River Mainstem OPEN APR. 1 to MAY 31 l 0 fish 3 over 63 cm 10 fish 10 fish 5 over 30 cm Mainstem OPEN JUNE 1 to MAR. 31 l 3 over 3 over 63 cm 10 fish 10 fish 5 over 43 cm 30 cm Tributaries except Clearwater and Hangingstone rivers OPEN JUNE 1 to OCT. 31 l 3 over 3 over 63 cm 10 fish 10 fish 10 fish 5 over 43 cm 30 cm Birch Creek Beyond 10 km of Christina Lake OPEN JUNE 1 to OCT. 31 l 0 fish 3 over 63 cm Christina Lake Tributaries and Includes all tributaries and outflows within 10km of OPEN JUNE 1 to OCT. 31 l 0 fish 0 fish 15 fish 10 fish 10 fish Outflows Christina Lake including Jackfish River, Birch, Sunday and Monday Creeks Clearwater River Snye Channel OPEN JUNE 1 to OCT. -

Northwest Territories Territoires Du Nord-Ouest British Columbia

122° 121° 120° 119° 118° 117° 116° 115° 114° 113° 112° 111° 110° 109° n a Northwest Territories i d i Cr r eighton L. T e 126 erritoires du Nord-Oues Th t M urston L. h t n r a i u d o i Bea F tty L. r Hi l l s e on n 60° M 12 6 a r Bistcho Lake e i 12 h Thabach 4 d a Tsu Tue 196G t m a i 126 x r K'I Tue 196D i C Nare 196A e S )*+,-35 125 Charles M s Andre 123 e w Lake 225 e k Jack h Li Deze 196C f k is a Lake h Point 214 t 125 L a f r i L d e s v F Thebathi 196 n i 1 e B 24 l istcho R a l r 2 y e a a Tthe Jere Gh L Lake 2 2 aili 196B h 13 H . 124 1 C Tsu K'Adhe L s t Snake L. t Tue 196F o St.Agnes L. P 1 121 2 Tultue Lake Hokedhe Tue 196E 3 Conibear L. Collin Cornwall L 0 ll Lake 223 2 Lake 224 a 122 1 w n r o C 119 Robertson L. Colin Lake 121 59° 120 30th Mountains r Bas Caribou e e L 118 v ine i 120 R e v Burstall L. a 119 l Mer S 117 ryweather L. 119 Wood A 118 Buffalo Na Wylie L. m tional b e 116 Up P 118 r per Hay R ark of R iver 212 Canada iv e r Meander 117 5 River Amber Rive 1 Peace r 211 1 Point 222 117 M Wentzel L. -

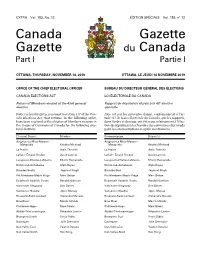

Canada Gazette, Part I

EXTRA Vol. 153, No. 12 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 153, no 12 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2019 OTTAWA, LE JEUDI 14 NOVEMBRE 2019 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER BUREAU DU DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 43rd general Rapport de député(e)s élu(e)s à la 43e élection election générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Can- Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’ar- ada Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, ticle 317 de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, have been received of the election of Members to serve in dans l’ordre ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élec- the House of Commons of Canada for the following elec- tion de député(e)s à la Chambre des communes du Canada toral districts: pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral District Member Circonscription Député(e) Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Matapédia Kristina Michaud Matapédia Kristina Michaud La Prairie Alain Therrien La Prairie Alain Therrien LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Burnaby South Jagmeet Singh Burnaby-Sud Jagmeet Singh Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke Randall Garrison Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke -

In Situ Report Card

Drilling DEEPERTHE IN SITU OIL SANDS REPORT CARD JEREMY MOORHOUSE • MARC HUOT • SIMON DYER March 2010 Oil SANDSFever SERIES Drilling Deeper The In Situ Oil Sands Report Card Jeremy Moorhouse Marc Huot Simon Dyer March 2010 The In Situ Oil Sands Report Card About the Pembina Institute The Pembina Institute The Pembina Institute is a national The Pembina Institute provides policy Box 7558 non-profit think tank that advances research leadership and education on Drayton Valley, Alberta, T7A 1S7 sustainable energy solutions through climate change, energy issues, green Phone: 780-542-6272 research, education, consulting and economics, energy efficiency and advocacy. It promotes environmental, conservation, renewable energy, and E-mail: [email protected] social and economic sustainability in environmental governance. For more the public interest by developing information about the Pembina practical solutions for communities, Institute, visit www.pembina.org or individuals, governments and businesses. contact info @pembina.org. Acknowledgements The Pembina Institute thanks the graciously reviewed and commented William and Flora Hewlett Foundation on the data the Pembina Institute for its support of this work. The had collected for this analysis. Their Pembina Institute would also like to comments and insights improved acknowledge the support of Cenovus, the quality of this report and the Shell and Husky for participating in this Pembina Institute’s understanding process. Each of these companies of in situ operations. ii DRILLING DEEPER: THE IN SITU OIL SANDS REPORT CARD The Pembina Institute The In Situ Oil Sands Report Card About the Authors Jeremy Moorhouse of Alberta, and a Master of Arts in Technical Analyst natural sciences Jeremy is a Technical Analyst with the from Cambridge Pembina Institute’s Corporate University. -

Craigdarroch Military Hospital: a Canadian War Story

Craigdarroch Military Hospital: A Canadian War Story Bruce Davies Curator © Craigdarroch Castle 2016 2 Abstract As one of many military hospitals operated by the federal government during and after The Great War of 1914-1918, the Dunsmuir house “Craigdarroch” is today a lens through which museum staff and visitors can learn how Canada cared for its injured and disabled veterans. Broad examination of military and civilian medical services overseas, across Canada, and in particular, at Craigdarroch, shows that the Castle and the Dunsmuir family played a significant role in a crucial period of Canada’s history. This paper describes the medical care that wounded and sick Canadian soldiers encountered in France, Belgium, Britain, and Canada. It explains some of the measures taken to help permanently disabled veterans successfully return to civilian life. Also covered are the comprehensive building renovations made to Craigdarroch, the hospital's official opening by HRH The Prince of Wales, and the question of why the hospital operated so briefly. By highlighting the wartime experiences of one Craigdarroch nurse and one Craigdarroch patient, it is seen that opportunities abound for rich story- telling in a new gallery now being planned for the museum. The paper includes an appendix offering a synopsis of the Dunsmuir family’s contributions to the War. 3 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................. 04 I. Canadian Medical Services -

The Implications of the Delgamuukw Decision on the Douglas Treaties"

James Douglas meet Delgamuukw "The implications of the Delgamuukw decision on the Douglas Treaties" The latest decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in Delgamuukw vs. The Queen, [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1010, has shed new light on aboriginal title and its relationship to treaties. The issue of aboriginal title has been of particular importance in British Columbia. The question of who owns British Columbia has been the topic of dispute since the arrival and settlement by Europeans. Unlike other parts of Canada, few treaties have been negotiated with the majority of First Nations. With the exception of treaty 8 in the extreme northeast corner of the province, the only other treaties are the 14 entered into by James Douglas, dealing with small tracts of land on Vancouver Island. Following these treaties, the Province of British Columbia developed a policy that in effect did not recognize aboriginal title or alternatively assumed that it had been extinguished, resulting in no further treaties being negotiated1. This continued to be the policy until 1990 when British Columbia agreed to enter into the treaty negotiation process, and the B.C. Treaty Commission was developed. The Nisga Treaty is the first treaty to be negotiated since the Douglas Treaties. This paper intends to explore the Douglas Treaties and the implications of the Delgamuukw decision on these. What assistance does Delgamuukw provide in determining what lands are subject to aboriginal title? What aboriginal title lands did the Douglas people give up in the treaty process? What, if any, aboriginal title land has survived the treaty process? 1 Joseph Trutch, Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works and Walter Moberly, Assistant Surveyor- General, initiated this policy. -

Claim of Aboriginal Ownership Chief David Latasse Was Present At

#6 Sources on the Douglas Treaties Douglas Treaties Document #1: Claim of Aboriginal Ownership Chief David Latasse was present at the treaty negotiations in Victoria in 1850. His recollections were recorded in 1934 when he was reportedly 105 years old: For some time after the whites commenced building their settlement they ferried their supplies ashore. Then they desired to build a dock, where ships could be tied up close to shore. Explorers found suitable timbers could be obtained at Cordova Bay, and a gang of whites, Frenchmen and Kanakas [Hawaiians] were sent there to cut piles. The first thing they did was set a fire which nearly got out of hand, making such smoke as to attract attention of the Indians for forty miles around. Chief Hotutstun of Salt Spring sent messengers to chief Whutsaymullet of the Saanich tribes, telling him that the white men were destroying his heritage and would frighten away fur and game animals. They met and jointly manned two big canoes and came down the coast to see what damage was being done and to demand pay from Douglas. Hotutstun was interested by the prospect of sharing in any gifts made to Whutsaymullet but also, indirectly, as the Chief Paramount of all the Indians of Saanich. As the two canoes rounded the point and paddled into Cordova Bay they were seen by camp cooks of the logging party, who became panic stricken. Rushing into the woods they yelled the alarm of Indians on the warpath. Every Frenchman and Kanaka dropped his tool and took to his heels, fleeing through the woods to Victoria. -

Language List 2019

First Nations Languages in British Columbia – Revised June 2019 Family1 Language Name2 Other Names3 Dialects4 #5 Communities Where Spoken6 Anishnaabemowin Saulteau 7 1 Saulteau First Nations ALGONQUIAN 1. Anishinaabemowin Ojibway ~ Ojibwe Saulteau Plains Ojibway Blueberry River First Nations Fort Nelson First Nation 2. Nēhiyawēwin ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ Saulteau First Nations ALGONQUIAN Cree Nēhiyawēwin (Plains Cree) 1 West Moberly First Nations Plains Cree Many urban areas, especially Vancouver Cheslatta Carrier Nation Nak’albun-Dzinghubun/ Lheidli-T’enneh First Nation Stuart-Trembleur Lake Lhoosk’uz Dene Nation Lhtako Dene Nation (Tl’azt’en, Yekooche, Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Nak’azdli) Nak’azdli Whut’en ATHABASKAN- ᑕᗸᒡ NaZko First Nation Saik’uz First Nation Carrier 12 EYAK-TLINGIT or 3. Dakelh Fraser-Nechakoh Stellat’en First Nation 8 Taculli ~ Takulie NA-DENE (Cheslatta, Sdelakoh, Nadleh, Takla Lake First Nation Saik’uZ, Lheidli) Tl’azt’en Nation Ts’il KaZ Koh First Nation Ulkatcho First Nation Blackwater (Lhk’acho, Yekooche First Nation Lhoosk’uz, Ndazko, Lhtakoh) Urban areas, especially Prince George and Quesnel 1 Please see the appendix for definitions of family, language and dialect. 2 The “Language Names” are those used on First Peoples' Language Map of British Columbia (http://fp-maps.ca) and were compiled in consultation with First Nations communities. 3 The “Other Names” are names by which the language is known, today or in the past. Some of these names may no longer be in use and may not be considered acceptable by communities but it is useful to include them in order to assist with the location of language resources which may have used these alternate names. -

Letter to Minister Leblanc

24959 ALOUETTE ROAD, MAPLE RIDGE, BC V4R 1R8 Tel: 604.467.6401 Fax: 604.467.6478 [email protected] www.alouetteriver.org 8 November, 2016 The Honourable Dominic LeBlanc Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard House of Commons Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A6 Re: Fisheries Act Review On behalf of the Alouette River Management Society’s Board of Directors, I would like to strongly urge the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard to: Act on recommendations of the Cohen Commission on restoring sockeye salmon stocks in the Fraser River, Work with the Minister of Transport to review the previous government’s changes to the Fisheries and Navigable Waters Protection Acts, restore lost protections, and incorporate modern safeguards, and Provide adequate resources for monitoring and enforcement to DFO. These priorities draw heavily from your government’s election platform commitments. As part of the Government of Canada’s recent request for public consultation on changes to the Fisheries Act, we recommend amending the Fisheries Act to: 1. Restore habitat protection for all native fish, not just those that are part of or are deemed to support an established fishery. 2. Bring back the harmful alteration, disruption and destruction (HADD) prohibition, but keep the expansion of the prohibition that was introduced with the changes to include “activities”. Thus the provision should read: “No person shall carry on any work, undertaking or activity that results in the harmful alteration, disruption or destruction of fish habitat.” 3. Reverse the repeal of section 32, the prohibition against the destruction of fish by means other than fishing, which has left a gap in the protection of fish. -

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory: Table of Contents and Section Descriptions 1. Linguistic Resources Academic linguistics articles, reference materials, and online language resources for each BC First Nations language. 2. Language-Specific Resources Practical teaching resources and curriculum identified for each BC First Nations language. 3. Adaptable Resources General curriculum and teaching resources which can be adapted for teaching BC First Nations languages: books, curriculum documents, online and multimedia resources. Includes copies of many documents in PDF format. 4. Language Revitalization Resources This section includes general resources on language revitalization, as well as resources on awakening languages, teaching methods for language revitalization, materials and activities for language teaching, assessing the state of a language, envisioning and planning a language program, teacher training, curriculum design, language acquisition, and the role of technology in language revitalization. 5. Language Teaching Journals A list of journals relevant to teachers of BC First Nations languages. 6. Further Education This section highlights opportunities for further education, training, certification, and professional development. It includes a list of conferences and workshops relevant to BC First Nations language teachers, and a spreadsheet of post‐ secondary programs relevant to Aboriginal Education and Teacher Training - in BC, across Canada, in the USA, and around the world. 7. Funding This section includes a list of funding sources for Indigenous language revitalization programs, as well as a list of scholarships and bursaries available for Aboriginal students and students in the field of Education, in BC, across Canada, and at specific institutions.