Enacting Privacy in Internet Standards by Nicholas P Doty A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Usask Open Textbook Authoring Guide – Ver.1.0

USask Open Textbook Authoring Guide – Ver.1.0 USask Open Textbook Authoring Guide – Ver.1.0 A Guide to Authoring & Adapting Open Textbooks at the University of Saskatchewan Distance Education Unit (DEU), University of Saskatchewan Jordan Epp, M.Ed., Kristine Dreaver-Charles, M.Sc.Ed., Jeanette McKee, M.Ed. Open Press DEU, Usask Saskatoon Copyright:2016 by Distance Education Unit, University of Saskatchewan. This book is an adaptation based on the B.C. Open Textbook Authoring Guide created by BCcampus and licensed with a CC-BY 4.0 license. Changes to the BCcampus Authoring Guide for this University of Saskatchewan adaptation included: Changing the references from BCcampus Open Project to be more relevant to the University of Saskatchewan’s open textbook development. Creation of a new title page and book title. Changing information about Support Services to be University of Saskatchewan specific. Performing a general text edit throughout the guide, added image captions, and updated most images to remove the BCcampus branding. Updating Pressbook platform nomenclature to be consistent with the current version of Pressbooks. Unless otherwise noted, this book is released under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) 4.0 Unported license. Under the terms of the CC-BY license you can freely share, copy or redistribute the material in any medium or format, or adapt the material by remixing, transforming or modifying this material providing you attribute the Distance Education Unit, University of Saskatchewan and BCcampus. Attribution means you must give appropriate credit to the Distance Education Unit, University of Saskatchewan and BCcampus as the original creator, note the CC-BY license this document has been released under, and indicate if you have made any changes to the content. -

Tuto Documentation Release 0.1.0

Tuto Documentation Release 0.1.0 DevOps people 2020-05-09 09H16 CONTENTS 1 Documentation news 3 1.1 Documentation news 2020........................................3 1.1.1 New features of sphinx.ext.autodoc (typing) in sphinx 2.4.0 (2020-02-09)..........3 1.1.2 Hypermodern Python Chapter 5: Documentation (2020-01-29) by https://twitter.com/cjolowicz/..................................3 1.2 Documentation news 2018........................................4 1.2.1 Pratical sphinx (2018-05-12, pycon2018)...........................4 1.2.2 Markdown Descriptions on PyPI (2018-03-16)........................4 1.2.3 Bringing interactive examples to MDN.............................5 1.3 Documentation news 2017........................................5 1.3.1 Autodoc-style extraction into Sphinx for your JS project...................5 1.4 Documentation news 2016........................................5 1.4.1 La documentation linux utilise sphinx.............................5 2 Documentation Advices 7 2.1 You are what you document (Monday, May 5, 2014)..........................8 2.2 Rédaction technique...........................................8 2.2.1 Libérez vos informations de leurs silos.............................8 2.2.2 Intégrer la documentation aux processus de développement..................8 2.3 13 Things People Hate about Your Open Source Docs.........................9 2.4 Beautiful docs.............................................. 10 2.5 Designing Great API Docs (11 Jan 2012)................................ 10 2.6 Docness................................................. -

Markdown Markup Languages What Is Markdown? Symbol

Markdown What is Markdown? ● Markdown is a lightweight markup language with plain text formatting syntax. Péter Jeszenszky – See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Markdown Faculty of Informatics, University of Debrecen [email protected] Last modified: October 4, 2019 3 Markup Languages Symbol ● Markup languages are computer languages for annotating ● Dustin Curtis. The Markdown Mark. text. https://dcurt.is/the-markdown-mark – They allow the association of metadata with parts of text in a https://github.com/dcurtis/markdown-mark clearly distinguishable way. ● Examples: – TeX, LaTeX https://www.latex-project.org/ – Markdown https://daringfireball.net/projects/markdown/ – troff (man pages) https://www.gnu.org/software/groff/ – XML https://www.w3.org/XML/ – Wikitext https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Help:Wikitext 2 4 Characteristics Usage (2) ● An easy-to-read and easy-to-write plain text ● Collaboration platforms and tools: format that. – GitHub https://github.com/ ● Can be converted to various output formats ● See: Writing on GitHub (e.g., HTML). https://help.github.com/en/categories/writing-on-github – Trello https://trello.com/ ● Specifically targeted at non-technical users. ● See: How To Format Your Text in Trello ● The syntax is mostly inspired by the format of https://help.trello.com/article/821-using-markdown-in-trell o plain text email. 5 7 Usage (1) Usage (3) ● Markdown is widely used on the web for ● Blogging platforms and content management entering text. systems: – ● The main application areas include: Ghost https://ghost.org/ -

The R Journal Volume 4/2, December 2012

The Journal Volume 4/2, December 2012 A peer-reviewed, open-access publication of the R Foundation for Statistical Computing Contents Editorial . .3 Contributed Research Articles What’s in a Name? . .5 It’s Not What You Draw, It’s What You Don’t Draw . 13 Debugging grid Graphics . 19 frailtyHL: A Package for Fitting Frailty Models with H-likelihood . 28 influence.ME: Tools for Detecting Influential Data in Mixed Effects Models . 38 The crs Package: Nonparametric Regression Splines for Continuous and Categorical Predic- tors.................................................... 48 Rfit: Rank-based Estimation for Linear Models . 57 Graphical Markov Models with Mixed Graphs in R . 65 Programmer’s Niche The State of Naming Conventions in R . 74 News and Notes Changes in R . 76 Changes on CRAN . 80 News from the Bioconductor Project . 101 R Foundation News . 102 2 The Journal is a peer-reviewed publication of the R Foun- dation for Statistical Computing. Communications regarding this pub- lication should be addressed to the editors. All articles are licensed un- der the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license (CC BY 3.0, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/). Prospective authors will find detailed and up-to-date submission in- structions on the Journal’s homepage. Editor-in-Chief: Martyn Plummer Editorial Board: Heather Turner, Hadley Wickham, and Deepayan Sarkar Editor Help Desk: Uwe Ligges Editor Book Reviews: G. Jay Kerns Department of Mathematics and Statistics Youngstown State University Youngstown, Ohio 44555-0002 USA [email protected] R Journal Homepage: http://journal.r-project.org/ Email of editors and editorial board: [email protected] The R Journal is indexed/abstracted by EBSCO, DOAJ, Thomson Reuters. -

Tecnologías Libres Para La Traducción Y Su Evaluación

FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS HUMANAS Y SOCIALES DEPARTAMENTO DE TRADUCCIÓN Y COMUNICACIÓN Tecnologías libres para la traducción y su evaluación Presentado por: Silvia Andrea Flórez Giraldo Dirigido por: Dra. Amparo Alcina Caudet Universitat Jaume I Castellón de la Plana, diciembre de 2012 AGRADECIMIENTOS Quiero agradecer muy especialmente a la Dra. Amparo Alcina, directora de esta tesis, en primer lugar por haberme acogido en el máster Tecnoloc y el grupo de investigación TecnoLeTTra y por haberme animado luego a continuar con mi investigación como proyecto de doctorado. Sus sugerencias y comentarios fueron fundamentales para el desarrollo de esta tesis. Agradezco también al Dr. Grabriel Quiroz, quien como profesor durante mi último año en la Licenciatura en Traducción en la Universidad de Antioquia (Medellín, Colombia) despertó mi interés por la informática aplicada a la traducción. De igual manera, agradezco a mis estudiantes de Traducción Asistida por Computador en la misma universidad por interesarse en el software libre y por motivarme a buscar herramientas alternativas que pudiéramos utilizar en clase sin tener que depender de versiones de demostración ni recurrir a la piratería. A mi colega Pedro, que comparte conmigo el interés por la informática aplicada a la traducción y por el software libre, le agradezco la oportunidad de llevar la teoría a la práctica profesional durante todos estos años. Quisiera agradecer a Esperanza, Anna, Verónica y Ewelina, compañeras de aventuras en la UJI, por haber sido mi grupo de apoyo y estar siempre ahí para escucharme en los momentos más difíciles. Mis más sinceros agradecimientos también a María por ser esa voz de aliento y cordura que necesitaba escuchar para seguir adelante y llegar a feliz término con este proyecto. -

Translate Toolkit Documentation Release 2.0.0

Translate Toolkit Documentation Release 2.0.0 Translate.org.za Sep 01, 2017 Contents 1 User’s Guide 3 1.1 Features..................................................3 1.2 Installation................................................4 1.3 Converters................................................6 1.4 Tools................................................... 57 1.5 Scripts.................................................. 96 1.6 Use Cases................................................. 107 1.7 Translation Related File Formats..................................... 124 2 Developer’s Guide 155 2.1 Translate Styleguide........................................... 155 2.2 Documentation.............................................. 162 2.3 Building................................................. 165 2.4 Testing.................................................. 166 2.5 Command Line Functional Testing................................... 168 2.6 Contributing............................................... 170 2.7 Translate Toolkit Developers Guide................................... 172 2.8 Making a Translate Toolkit Release................................... 176 2.9 Deprecation of Features......................................... 181 3 Additional Notes 183 3.1 Release Notes.............................................. 183 3.2 Changelog................................................ 246 3.3 History of the Translate Toolkit..................................... 254 3.4 License.................................................. 256 4 API Reference 257 4.1 -

Pipenightdreams Osgcal-Doc Mumudvb Mpg123-Alsa Tbb

pipenightdreams osgcal-doc mumudvb mpg123-alsa tbb-examples libgammu4-dbg gcc-4.1-doc snort-rules-default davical cutmp3 libevolution5.0-cil aspell-am python-gobject-doc openoffice.org-l10n-mn libc6-xen xserver-xorg trophy-data t38modem pioneers-console libnb-platform10-java libgtkglext1-ruby libboost-wave1.39-dev drgenius bfbtester libchromexvmcpro1 isdnutils-xtools ubuntuone-client openoffice.org2-math openoffice.org-l10n-lt lsb-cxx-ia32 kdeartwork-emoticons-kde4 wmpuzzle trafshow python-plplot lx-gdb link-monitor-applet libscm-dev liblog-agent-logger-perl libccrtp-doc libclass-throwable-perl kde-i18n-csb jack-jconv hamradio-menus coinor-libvol-doc msx-emulator bitbake nabi language-pack-gnome-zh libpaperg popularity-contest xracer-tools xfont-nexus opendrim-lmp-baseserver libvorbisfile-ruby liblinebreak-doc libgfcui-2.0-0c2a-dbg libblacs-mpi-dev dict-freedict-spa-eng blender-ogrexml aspell-da x11-apps openoffice.org-l10n-lv openoffice.org-l10n-nl pnmtopng libodbcinstq1 libhsqldb-java-doc libmono-addins-gui0.2-cil sg3-utils linux-backports-modules-alsa-2.6.31-19-generic yorick-yeti-gsl python-pymssql plasma-widget-cpuload mcpp gpsim-lcd cl-csv libhtml-clean-perl asterisk-dbg apt-dater-dbg libgnome-mag1-dev language-pack-gnome-yo python-crypto svn-autoreleasedeb sugar-terminal-activity mii-diag maria-doc libplexus-component-api-java-doc libhugs-hgl-bundled libchipcard-libgwenhywfar47-plugins libghc6-random-dev freefem3d ezmlm cakephp-scripts aspell-ar ara-byte not+sparc openoffice.org-l10n-nn linux-backports-modules-karmic-generic-pae -

Technical Workflows and Tools for Experimental Publishing

COPIM • Books Contain Multitudes: Exploring Experimental Publishing Part 3: Technical Workows and Tools for Experimental Publishing Marcell Mars, Tobias Steiner, Janneke Adema Published on: Jan 29, 2021 DOI: 10.21428/785a6451.174760b2 License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0) COPIM • Books Contain Multitudes: Exploring Experimental Publishing Part 3: Technical Workows and Tools for Experimental Publishing For this third part of the scoping report, we will be looking at the technical developments around experimental book publishing. We will be doing so in a three-fold manner in the next three sections. First, instead of conducting a landscape study ourselves, we will be reviewing a number of studies and resources that have recently been released and that have tried to categorise, analyse, and map the open source publishing tools and platforms currently available to support open access (book) publishing. Our focus in this analysis will predominantly be on those tools and technologies that can support the kinds of experimental publications that we have identified in the first two parts of this scoping report. Secondly, in section 2, we will outline a proposed methodology to analyse and categorise the currently available tools and technologies to support the creation of an online resource for publishers and authors in year 3 of the COPIM project. This online resource will include the technological support and workflows available to enable more experimental forms of book publishing, whilst showcasing examples and best practices for different levels of technical know-how. Thirdly, in section 3, we will make an initial attempt at categorising a selection of tools following this proposed methodology, where we will be focusing on collaborative writing tools and on annotation tools —and the software, platforms, and workflows that support these—in first instance. -

Highly Integrated Urban Energy, Water and Waste Systems

Highly integrated urban energy, water and waste systems Thomas Ravalde December 2018 Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Civil and Environmental Engineering of Imperial College London Copyright and license The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and is made available under a Creative Commons At- tribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives licence. Researchers are free to copy, distribute or transmit the thesis on the condition that they attribute it, that they do not use if for commercial purposes and that they do not alter, transform or build upon it. For any reuse or redistribution, researchers must make clear to others the licence terms of this work. Declaration of originality I declare that this thesis is my own work, and that the work of others is appropriately referenced and acknowledged. Revision fc5cfd1 on 2018-12-11 1 Abstract Urbanisation continues to bring socioeconomic well-being to an ever-growing global urban popula- tion. Nevertheless, there is an environmental and economic imperative for cities to use resources more sustainably. One way to achieve this is to take advantage of the fact that, in cities, resource man- agement infrastructure from the energy, water and waste sectors is co-located, such that the wastes and by-products from one process can become the inputs to another (for example, sending organic waste to anaerobic digestion to produce biogas for energy generation). This thesis provides planners and policy makers with means to begin realising these intersectoral synergies, through contributions to the field of urban metabolism. First, a conceptual model is developed which can describe how a city’s mix of processes affect is metabolism. -

Markdown Dan Pandoc

Seri Manajemen Proyek Software Markdown dan Pandoc Membuat dokumentasi dengan Markdown dan Pandoc Endy Muhardin 5 September 2012 Versi: 1.1 © 2013 ArtiVisi Intermedia Markdown dan Pandoc v1.1 Daftar Isi 1 Pendahuluan1 1.1 Tentang Markdown........................1 1.1.1 Apa itu Markdown....................1 1.1.2 Mengapa memilih Markdown.............1 1.2 Tentang Pandoc..........................3 1.3 Tentang Buku Ini.........................4 1.3.1 Mengapa buku ini ditulis................4 1.3.2 Siapa yang sebaiknya membaca.............4 1.3.3 Lisensi...........................4 1.3.4 Tools............................5 1.3.5 Kontribusi.........................5 1.3.6 Reviewer..........................5 1.3.7 Penulis...........................5 2 Sintaks Markdown7 2.1 Paragraf..............................8 2.2 Headers..............................8 2.2.1 Pemberian ID untuk Header..............8 2.3 Kutipan...............................9 2.4 Kode Program........................... 10 2.5 List dan Nomor.......................... 10 2.5.1 List............................. 10 2.5.2 Nomor........................... 11 2.6 Garis Mendatar.......................... 12 2.7 Tabel................................ 13 2.8 Cover................................ 14 2.9 Backslash.............................. 14 2.10 Inline Formatting......................... 15 Markdown dan Pandoc Daftar Isi 2.10.1 Huruf Miring....................... 15 2.10.2 Huruf Tebal........................ 15 2.10.3 Strikeout.......................... 15 2.10.4 Verbatim......................... -

Towards Left Duff S Mdbg Holt Winters Gai Incl Tax Drupal Fapi Icici

jimportneoneo_clienterrorentitynotfoundrelatedtonoeneo_j_sdn neo_j_traversalcyperneo_jclientpy_neo_neo_jneo_jphpgraphesrelsjshelltraverserwritebatchtransactioneventhandlerbatchinsertereverymangraphenedbgraphdatabaseserviceneo_j_communityjconfigurationjserverstartnodenotintransactionexceptionrest_graphdbneographytransactionfailureexceptionrelationshipentityneo_j_ogmsdnwrappingneoserverbootstrappergraphrepositoryneo_j_graphdbnodeentityembeddedgraphdatabaseneo_jtemplate neo_j_spatialcypher_neo_jneo_j_cyphercypher_querynoe_jcypherneo_jrestclientpy_neoallshortestpathscypher_querieslinkuriousneoclipseexecutionresultbatch_importerwebadmingraphdatabasetimetreegraphawarerelatedtoviacypherqueryrecorelationshiptypespringrestgraphdatabaseflockdbneomodelneo_j_rbshortpathpersistable withindistancegraphdbneo_jneo_j_webadminmiddle_ground_betweenanormcypher materialised handaling hinted finds_nothingbulbsbulbflowrexprorexster cayleygremlintitandborient_dbaurelius tinkerpoptitan_cassandratitan_graph_dbtitan_graphorientdbtitan rexter enough_ram arangotinkerpop_gremlinpyorientlinkset arangodb_graphfoxxodocumentarangodborientjssails_orientdborientgraphexectedbaasbox spark_javarddrddsunpersist asigned aql fetchplanoriento bsonobjectpyspark_rddrddmatrixfactorizationmodelresultiterablemlibpushdownlineage transforamtionspark_rddpairrddreducebykeymappartitionstakeorderedrowmatrixpair_rddblockmanagerlinearregressionwithsgddstreamsencouter fieldtypes spark_dataframejavarddgroupbykeyorg_apache_spark_rddlabeledpointdatabricksaggregatebykeyjavasparkcontextsaveastextfilejavapairdstreamcombinebykeysparkcontext_textfilejavadstreammappartitionswithindexupdatestatebykeyreducebykeyandwindowrepartitioning -

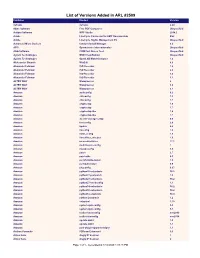

List of Versions Added in ARL #2509

List of Versions Added in ARL #2509 Publisher Product Version 3uTools 3uTools 2.20 4dots Software Free PDF Compress Unspecified Actipro Software WPF Studio 2014.2 Adobe LiveCycle Connector for EMC Documentum ES2 Adobe LiveCycle Rights Management ES Unspecified Advanced Micro Devices Catalyst Install Manager 8.0 AFIP Operaciones Internacionales Unspecified AGG Software COM Port Stress Test Unspecified Agilent Technologies MSD ChemStation Unspecified Agilent Technologies OpenLAB MatchCompare 1.0 Aleksander Simonic WinEdt 8.0 Alexander Feinman ISO Recorder 1.0 Alexander Feinman ISO Recorder 2.0 Alexander Feinman ISO Recorder 3.0 Alexander Feinman ISO Recorder 3.1 ALTER WAY WampServer 2 ALTER WAY WampServer 3.0 ALTER WAY WampServer 3.1 Amazon authconfig 6.2 Amazon chkconfig 1.3 Amazon chkconfig 1.7 Amazon cryptsetup 1.6 Amazon cryptsetup 1.7 Amazon cryptsetup-libs 1.6 Amazon cryptsetup-libs 1.7 Amazon docker-storage-setup 0.6 Amazon fontconfig 2.8 Amazon kpatch 0.4 Amazon libconfig 1.4 Amazon libini_config 1.3 Amazon libnetfilter_cthelper 1.0 Amazon mesa-dri-drivers 17.1 Amazon multilib-rpm-config 1 Amazon mysql-config 5.5 Amazon patch 2.7 Amazon patchutils 0.3 Amazon perl-ExtUtils-Install 1.5 Amazon perl-Sub-Install 0.9 Amazon pkgconfig 0.27 Amazon python26-setuptools 36.2 Amazon python27-jsonpatch 1.2 Amazon python27-setuptools 36.2 Amazon python27-sssdconfig 1.1 Amazon python34-setuptools 36.2 Amazon python36-setuptools 36.2 Amazon python3-setuptools 38.4 Amazon python-jsonpatch 1.2 Amazon setuptool 1.19 Amazon system-rpm-config 9.0 Amazon