On Archaeophis Proavus Mass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World at the Time of Messel: Conference Volume

T. Lehmann & S.F.K. Schaal (eds) The World at the Time of Messel - Conference Volume Time at the The World The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference 2011 Frankfurt am Main, 15th - 19th November 2011 ISBN 978-3-929907-86-5 Conference Volume SENCKENBERG Gesellschaft für Naturforschung THOMAS LEHMANN & STEPHAN F.K. SCHAAL (eds) The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference Frankfurt am Main, 15th – 19th November 2011 Conference Volume Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung IMPRINT The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference 15th – 19th November 2011, Frankfurt am Main, Germany Conference Volume Publisher PROF. DR. DR. H.C. VOLKER MOSBRUGGER Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany Editors DR. THOMAS LEHMANN & DR. STEPHAN F.K. SCHAAL Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected]; [email protected] Language editors JOSEPH E.B. HOGAN & DR. KRISTER T. SMITH Layout JULIANE EBERHARDT & ANIKA VOGEL Cover Illustration EVELINE JUNQUEIRA Print Rhein-Main-Geschäftsdrucke, Hofheim-Wallau, Germany Citation LEHMANN, T. & SCHAAL, S.F.K. (eds) (2011). The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates. 22nd International Senckenberg Conference. 15th – 19th November 2011, Frankfurt am Main. Conference Volume. Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, Frankfurt am Main. pp. 203. -

Snakes of the Siwalik Group (Miocene of Pakistan): Systematics and Relationship to Environmental Change

Palaeontologia Electronica http://palaeo-electronica.org SNAKES OF THE SIWALIK GROUP (MIOCENE OF PAKISTAN): SYSTEMATICS AND RELATIONSHIP TO ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE Jason J. Head ABSTRACT The lower and middle Siwalik Group of the Potwar Plateau, Pakistan (Miocene, approximately 18 to 3.5 Ma) is a continuous fluvial sequence that preserves a dense fossil record of snakes. The record consists of approximately 1,500 vertebrae derived from surface-collection and screen-washing of bulk matrix. This record represents 12 identifiable taxa and morphotypes, including Python sp., Acrochordus dehmi, Ganso- phis potwarensis gen. et sp. nov., Bungarus sp., Chotaophis padhriensis, gen. et sp. nov., and Sivaophis downsi gen. et sp. nov. The record is dominated by Acrochordus dehmi, a fully-aquatic taxon, but diversity increases among terrestrial and semi-aquatic taxa beginning at approximately 10 Ma, roughly coeval with proxy data indicating the inception of the Asian monsoons and increasing seasonality on the Potwar Plateau. Taxonomic differences between the Siwalik Group and coeval European faunas indi- cate that South Asia was a distinct biogeographic theater from Europe by the middle Miocene. Differences between the Siwalik Group and extant snake faunas indicate sig- nificant environmental changes on the Plateau after the last fossil snake occurrences in the Siwalik section. Jason J. Head. Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, Washington, DC 20013-7012, USA. [email protected] School of Biological Sciences, Queen Mary, University of London, London, E1 4NS, United Kingdom. KEY WORDS: Snakes, faunal change, Siwalik Group, Miocene, Acrochordus. PE Article Number: 8.1.18A Copyright: Society of Vertebrate Paleontology May 2005 Submission: 3 August 2004. -

A NOVEL GAIN of FUNCTION of the <I>IRX1</I> and <I>IRX2</I> GENES DISRUPTS AXIS ELONGATION in the ARAUCA

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 8-2013 A NOVEL GAIN OF FUNCTION OF THE IRX1 AND IRX2 GENES DISRUPTS AXIS ELONGATION IN THE ARAUCANA RUMPLESS CHICKEN Nowlan Freese Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Part of the Developmental Biology Commons Recommended Citation Freese, Nowlan, "A NOVEL GAIN OF FUNCTION OF THE IRX1 AND IRX2 GENES DISRUPTS AXIS ELONGATION IN THE ARAUCANA RUMPLESS CHICKEN" (2013). All Dissertations. 1198. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1198 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A NOVEL GAIN OF FUNCTION OF THE IRX1 AND IRX2 GENES DISRUPTS AXIS ELONGATION IN THE ARAUCANA RUMPLESS CHICKEN A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Biological Sciences by Nowlan Hale Freese August 2013 Accepted by: Dr. Susan C. Chapman, Committee Chair Dr. Lesly A. Temesvari Dr. Matthew W. Turnbull Dr. Leigh Anne Clark Dr. Lisa J. Bain ABSTRACT Caudal dysplasia describes a range of developmental disorders that affect normal development of the lumbar spinal column, sacrum and pelvis. An important goal of the congenital malformation field is to identify the genetic mechanisms leading to caudal deformities. To identify the genetic cause(s) and subsequent molecular mechanisms I turned to an animal model, the rumpless Araucana chicken breed. Araucana fail to form vertebrae beyond the level of the hips. -

Snake Skeletonizing Manual

Snake Skeletonizing Manual By Ellen Kuo Illustrations by Omar Malik, Juliana Olsson, and Sara Brenner © 2020 Museum of Vertebrate Zoology Table of Contents Snake anatomy reference images …………………………………………………. Page 2-3 Station setup …………………………………………………. Page 4 Initial data collection and setup …………………………………………………. Page 5-8 Taking photos …………………………………………………. Page 9 Initially determining the sex ………………………………………………… Page 9-10 Skinning …………………………………………………. Page 11-12 Opening and sexing …………………………………………………. Page 13-24 Examples of male gonads …………………………………………………. Page 14-16 Examples of female gonads …………………………………………………... Page 17-23 Taking tissues …………………………………………………. Page 25 Stomach contents, parasites …………………………………………………. Page 25 Finishing and cleaning up …………………………………………………. Page 26 1 Snake Anatomy References 2 Illustration by Sara Brenner Snake skeleton – note that the ribs go down the whole length of the body (they end at the vent, and then the tail does not have ribs). Illustration by Sara Brenner Most snake skulls consist of many small, delicate bones that are unfused. The lower jaw is not fused at the center, allowing the snake to use its lower jaws like arms to slowly feed in prey. Snakes have very sharp, delicate teeth, and lots, and lots, and lots of them — typically on several different jaw bones! Avoid disturbing the teeth. 3 Station Setup Materials ● Snake ● Original data ● Skeleton tag ● Gloves ● Worksheet ● Micron pen ● Forceps ● Scissors (large and small) ● Tray (optional) ● Camera* ● Ruler and/or measuring tape ● Tissue vial ● Vial pen* ● MVZ barcode (for tissue vial) ● Paper towel labeled with H, L, M, K ● Prep Lab Catalog* ● Extra paper towels (optional) ● Scale* ● Herp field guide (for local animals)* ● Probe ● Biohazard bin* *shared materials with the rest of the class 4 Before you start cutting ● Set up your station with all of the listed materials (or access to them) ● Identify the genus and species of your specimen, double checking with the class coordinator to make sure it is correct. -

Briefly Foreign Aid to Small Island Nations in Gests That Deserts May Be Among Those Return for Their Support Within the Ecosystems Most Affected

the buying of votes by promising to give Nations Environment Programme sug- Briefly foreign aid to small island nations in gests that deserts may be among those return for their support within the ecosystems most affected. Climatic commission. It seems, however, that pulses are more important than average these tactics are similar to those insti- conditions in desert ecosystems, and gated by Peter Scott, then head of WWF, because of this even moderate changes International to obtain the original moratorium on in precipitation and temperature can whaling. Evidence shows that many of have a severe impact. Contrary to the countries that voted in favour of the appearance, the 3.7 million km2 of the moratorium in 1982 had been offered world’s deserts provide a habitat for Hope for coral reefs help with providing suitable delegates many species, which will be adversely Many coral species are sensitive to rises and expenses. Scott’s biographer writes affected should the report’s projected in ocean temperature, and coral bleach- that China’s decision to join the IWC scenario of an increase in desert tem- ing events have increased in frequency and vote for the moratorium was influ- perature by 7˚C and a decrease in rain- in recent years. Now researchers have enced by a WWF promise to provide fall of 20% prove correct. However, shown that some corals may be able USD 1 million towards a panda reserve. deserts could also have a role to play to acclimatize to higher temperatures. Source: New Scientist (2006), 190(2556), in mitigating future environmental Experiments involving the hard coral 14. -

NHBSS 061 1G Hikida Fieldg

Book Review N$7+IST. BULL. S,$0 SOC. 61(1): 41–51, 2015 A Field Guide to the Reptiles of Thailand by Tanya Chan-ard, John W. K. Parr and Jarujin Nabhitabhata. Oxford University Press, New York, 2015. 344 pp. paper. ISBN: 9780199736492. 7KDLUHSWLOHVZHUHÀUVWH[WHQVLYHO\VWXGLHGE\WZRJUHDWKHUSHWRORJLVWV0DOFROP$UWKXU 6PLWKDQG(GZDUG+DUULVRQ7D\ORU7KHLUFRQWULEXWLRQVZHUHSXEOLVKHGDV6MITH (1931, 1935, 1943) and TAYLOR 5HFHQWO\RWKHUERRNVDERXWUHSWLOHVDQGDPSKLELDQV LQ7KDLODQGZHUHSXEOLVKHG HJ&HAN-ARD ET AL., 1999: COX ET AL DVZHOODVPDQ\ SDSHUV+RZHYHUWKHVHERRNVZHUHWD[RQRPLFVWXGLHVDQGQRWJXLGHVIRURUGLQDU\SHRSOH7ZR DGGLWLRQDOÀHOGJXLGHERRNVRQUHSWLOHVRUDPSKLELDQVDQGUHSWLOHVKDYHDOVREHHQSXEOLVKHG 0ANTHEY & GROSSMANN, 1997; DAS EXWWKHVHERRNVFRYHURQO\DSDUWRIWKHIDXQD The book under review is very well prepared and will help us know Thai reptiles better. 2QHRIWKHDXWKRUV-DUXMLQ1DEKLWDEKDWDZDVP\ROGIULHQGIRUPHUO\WKH'LUHFWRURI1DWXUDO +LVWRU\0XVHXPWKH1DWLRQDO6FLHQFH0XVHXP7KDLODQG+HZDVDQH[FHOOHQWQDWXUDOLVW DQGKDGH[WHQVLYHNQRZOHGJHDERXW7KDLDQLPDOVHVSHFLDOO\DPSKLELDQVDQGUHSWLOHV,Q ZHYLVLWHG.KDR6RL'DR:LOGOLIH6DQFWXDU\WRVXUYH\KHUSHWRIDXQD+HDGYLVHGXV WRGLJTXLFNO\DURXQGWKHUH:HFROOHFWHGIRXUVSHFLPHQVRIDibamusZKLFKZHGHVFULEHG DVDQHZVSHFLHVDibamus somsaki +ONDA ET AL 1RZ,DPYHU\JODGWRNQRZWKDW WKLVERRNZDVSXEOLVKHGE\KLPDQGKLVFROOHDJXHV8QIRUWXQDWHO\KHSDVVHGDZD\LQ +LVXQWLPHO\GHDWKPD\KDYHGHOD\HGWKHSXEOLFDWLRQRIWKLVERRN7KHERRNLQFOXGHVQHDUO\ DOOQDWLYHUHSWLOHV PRUHWKDQVSHFLHV LQ7KDLODQGDQGPRVWSLFWXUHVZHUHGUDZQZLWK H[FHOOHQWGHWDLO,WLVDYHU\JRRGÀHOGJXLGHIRULGHQWLÀFDWLRQRI7KDLUHSWLOHVIRUVWXGHQWV -

Kansas Herpetological Society Newsletter No. 54 December, 1983

KANSAS HERPETOLOGICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER NO. 54 DECEMBER, 1983 1984 KHS DUES DUE, DO ... In this issue of the KHS Newsletter, you should find the nifty return-by-mail envelope for payment of your 1984 Kansas Herpetological Society dues. Since your dues are what finances this newsletter, prompt payment is appreciated. If you have already paid your 1984 dues, pass the envelope on to a friend who would like to JO~n the Kansas Herpetological Society. Of all the Regional Herpetological Societies in the U.S . , the KHS has some of the LO\fEST membership rates. If you are missing your dues envelope, or have lost it, the rates are still as follows: Regular member (U.S . ) $4.00 Non-U .S. member $8.00 Contributing member $15.00 Make your checks or money orders payable to KHS. Be sure that your CORRECT mailing address is printed neatly on the outside of the envelope. Send your money to: Kansas Herpetological Society Museum of Natural History University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 66045 KHS NEWSLETTER NO. 54 1 ANNOUNCENENTS Who Are Those Herpetologists, Anyway? If you are in the mood to expand your Christmas card list, here is a chance to get the names and addresses of over 2,000 professional and amateur herpetologists, plus lots of other neat stuff. The Silver Anniversary Membership Directory of the Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles has just been published and also contains a list of herpetological societies and organizations of the world (organized by country, each listing includes an address to write to and usually a list of publications) , a brief history of the SSAR, and other useful information about the SSAR and its organization. -

Zootaxa, Phylogeny and Biogeography of the Enhydris Clade

Zootaxa 2452: 18–30 (2010) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2010 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Phylogeny and biogeography of the Enhydris clade (Serpentes: Homalopsidae) DARYL R. KARNS1,2, VIMOKSALEHI LUKOSCHEK2,3, JENNIFER OSTERHAGE1,2, JOHN C. MURPHY2 & HAROLD K. VORIS2,4 1Department of Biology, Rivers Institute, Hanover College, Hanover, IN 47243. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Zoology, Field Museum of Natural History, 1400 South Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL 60605. E-mail: [email protected] 3Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Irvine, CA, 92697. E-mail: [email protected] 4Corresponding author. E-mail [email protected] Abstract Previous molecular phylogenetic hypotheses for the Homalopsidae, the Oriental-Australian Rear-fanged Water Snakes indicate that Enhydris, the most speciose genus in the Homalopsidae (22 of 37 species), is polyphyletic and may consist of five separate lineages. We expand on earlier phylogenetic hypotheses using three mitochondrial fragments and one nuclear gene, previously shown to be rapidly evolving in snakes, to determine relationships among six closely related species: Enhydris enhydris, E. subtaeniata, E. chinensis, E. innominata, E. jagorii, and E. longicauda. Four of these species (E. subtaeniata, E. innominata, E. jagorii, and E. longicauda) are restricted to river basins in Indochina, while E. chinensis is found in southern China and E. enhydris is widely distributed from India across Southeast Asia. Our phylogenetic analyses indicate that these species are monophyletic and we recognize this clade as the Enhydris clade sensu stricto for nomenclatural reasons. Our analysis shows that E. -

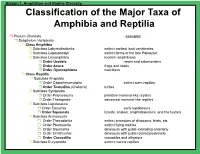

Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia

Station 1. Amphibian and Reptile Diversity Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia ! Phylum Chordata examples ! Subphylum Vertebrata ! Class Amphibia ! Subclass Labyrinthodontia extinct earliest land vertebrates ! Subclass Lepospondyli extinct forms of the late Paleozoic ! Subclass Lissamphibia modern amphibians ! Order Urodela newts and salamanders ! Order Anura frogs and toads ! Order Gymnophiona caecilians ! Class Reptilia ! Subclass Anapsida ! Order Captorhinomorpha extinct stem reptiles ! Order Testudina (Chelonia) turtles ! Subclass Synapsida ! Order Pelycosauria primitive mammal-like reptiles ! Order Therapsida advanced mammal-like reptiles ! Subclass Lepidosaura ! Order Eosuchia early lepidosaurs ! Order Squamata lizards, snakes, amphisbaenians, and the tuatara ! Subclass Archosauria ! Order Thecodontia extinct ancestors of dinosaurs, birds, etc ! Order Pterosauria extinct flying reptiles ! Order Saurischia dinosaurs with pubis extending anteriorly ! Order Ornithischia dinosaurs with pubis rotated posteriorly ! Order Crocodilia crocodiles and alligators ! Subclass Euryapsida extinct marine reptiles Station 1. Amphibian Skin AMPHIBIAN SKIN Most amphibians (amphi = double, bios = life) have a complex life history that often includes aquatic and terrestrial forms. All amphibians have bare skin - lacking scales, feathers, or hair -that is used for exchange of water, ions and gases. Both water and gases pass readily through amphibian skin. Cutaneous respiration depends on moisture, so most frogs and salamanders are -

Biological System Models Reproducing Snakes’ Musculoskeletal System

The 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems October 18-22, 2010, Taipei, Taiwan Biological System Models Reproducing Snakes’ Musculoskeletal System Kousuke Inoue, Kaita Nakamura, Masatoshi Suzuki, Yoshikazu Mori, Yasuhiro Fukuoka and Naoji Shiroma Abstract— Snakes are very unique animals that have dis- including the interaction in order to elucidate the mechanism tinguished motor function adaptable to the most diverse en- of emerging animals’ adaptive motor functions. vironments in terrestrial animals regardless of their simple cord-shaped body. Revealing the mechanism underlying this B. Previous works on snakes’ locomotion mechanisms distinct locomotion pattern, which is fundamentally different from walking, is signifficant not only in biolgical field but The researches on snakes in biology have been conducted also for applications in engineering firld. However, it has mainly on taxonomy, anatomy and snake poison and there been difficult to clarify this adaptive function, emerging from are few researches on snake locomotion until now. In lo- dynamic interaction between body, brain and environment, comotion studies [1]-[15], analytical discussions have been by previous scientific methodologies based on reductionism, carried out based on kinematics recording with respect to where understanding of the total system is approached by analyzing specific individual elements. In this research, we aim specific locomotion modes or EMG recording with a few at revealing the mechanisms underlying this adaptability by muscles that are said to be dominant for locomotion. For the use of the constructive methodology, in which biological example, Jayne [10] records EMG with the three dominant system models reflecting biological knowledge is used as a tool muscles with lateral undulation locomotion in terrestrial and for analysis of the total system. -

Histology of Watersnake (Enhydris Enhydris) Digestive System

E3S Web of Conferences 151, 01052 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202015101052 st 1 ICVAES 2019 Histology of Watersnake (Enhydris Enhydris) Digestive System Dian Masyitha1,*, Lena Maulidar 2 , Zainuddin Zainuddin1, Muhammad N. Salim3, Dwinna Aliza3, Fadli A. Gani 4 , Rusli Rusli5 1 Histology Laboratory of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Syiah Kuala University, Banda Aceh 23111, Indonesia 2 Veterinary Education Study Program Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Syiah Kuala University, Banda Aceh 23111, Indonesia 3 Pathology Laboratory, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala , Banda Aceh, Indonesia 4 Anatomy Laboratory, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala , Banda Aceh, Indonesia 5 Clinical Laboratory of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala , Banda Aceh, Indonesia Abstract. This research aimed to study the histology of the digestive system of the watersnake (Enhydris enhydris). The digestive system taken was the esophagus, stomach, frontal small intestine and the back of the large intestine from three watersnakes. The samples were then made into histological preparations with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining and observed exploratively. The results showed that the digestive system of the watersnake was composed of layers of tissue, namely the mucosa, tunica submucosa, tunica muscularis, and serous tunica. Mucosal mucosa consisted of the lamina epithelium, lamina propria, and mucous lamina muscularis. The submucosal tunica consisted of connective tissue with blood vessels, lymph, and nerves. The muscular tunica was composed of circular muscles and elongated muscles. The serous tunica consisted of a thin layer of connective tissue that was covered by a thin layer of the mesothelium (mesothelium). The histological structure of the snake digestive system is not much different from the reptile digestive system. -

Life After Logging: Reconciling Wildlife Conservation and Production Forestry in Indonesian Borneo

Life after logging Reconciling wildlife conservation and production forestry in Indonesian Borneo Erik Meijaard • Douglas Sheil • Robert Nasi • David Augeri • Barry Rosenbaum Djoko Iskandar • Titiek Setyawati • Martjan Lammertink • Ike Rachmatika • Anna Wong Tonny Soehartono • Scott Stanley • Timothy O’Brien Foreword by Professor Jeffrey A. Sayer Life after logging: Reconciling wildlife conservation and production forestry in Indonesian Borneo Life after logging: Reconciling wildlife conservation and production forestry in Indonesian Borneo Erik Meijaard Douglas Sheil Robert Nasi David Augeri Barry Rosenbaum Djoko Iskandar Titiek Setyawati Martjan Lammertink Ike Rachmatika Anna Wong Tonny Soehartono Scott Stanley Timothy O’Brien With further contributions from Robert Inger, Muchamad Indrawan, Kuswata Kartawinata, Bas van Balen, Gabriella Fredriksson, Rona Dennis, Stephan Wulffraat, Will Duckworth and Tigga Kingston © 2005 by CIFOR and UNESCO All rights reserved. Published in 2005 Printed in Indonesia Printer, Jakarta Design and layout by Catur Wahyu and Gideon Suharyanto Cover photos (from left to right): Large mature trees found in primary forest provide various key habitat functions important for wildlife. (Photo by Herwasono Soedjito) An orphaned Bornean Gibbon (Hylobates muelleri), one of the victims of poor-logging and illegal hunting. (Photo by Kimabajo) Roads lead to various impacts such as the fragmentation of forest cover and the siltation of stream— other impacts are associated with improved accessibility for people. (Photo by Douglas Sheil) This book has been published with fi nancial support from UNESCO, ITTO, and SwedBio. The authors are responsible for the choice and presentation of the facts contained in this book and for the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of CIFOR, UNESCO, ITTO, and SwedBio and do not commit these organisations.