Biological System Models Reproducing Snakes’ Musculoskeletal System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traversing Tight Tunnels—Implementing an Adaptive Concertina Gait in a Biomimetic Snake Robot Henry C

Earth and Space 2018 158 Traversing Tight Tunnels—Implementing an Adaptive Concertina Gait in a Biomimetic Snake Robot Henry C. Astley1 1Biomimicry Research and Innovation Center, Dept. of Biology and Polymer Science, Univ. of Akron, 235 Carroll St., Akron, OH 44325-3908. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Snakes move through cluttered habitats and tight spaces with extraordinary ease, and consequently snake robots are a popular design for such situations. The remarkable locomotor performance of snakes is due in part to their diversity of locomotor modes for addressing a range of environmental challenges. Concertina locomotion consists of alternating periods of static anchoring and movement along the snake’s body, and is used to negotiate narrow spaces such as tunnels or bare branches. However, concertina locomotion has rarely been implemented in snake robots. In this paper, the anchor formation process in live snakes during concertina locomotion is quantified and used to implement concertina locomotion in a snake robot, with automatic detection of the width of the tunnel walls to modulate the waveform. This allows effective concertina locomotion in tunnels of unknown width, without prior knowledge of tunnel geometry, expanding the range of gaits in snake robots. INTRODUCTION The elongate, limbless body plan is extremely common throughout nature, in both vertebrate and invertebrates alike (Pechenik, J. A. 2005; Pough, F. H. et al. 2002), and has evolved independently numerous times (Gans, C 1975). Indeed, within lizards (Order Squamata) alone there are over two dozen independent evolutions of limblessness or functional limblessness (Wiens, J. J. et al. 2006). Snakes are by far the most successful limbless taxon, with a near-global distribution, nearly 3000 species, and a wide range of ecological niches and habitats (Pough, F. -

Slithering Locomotion

SLITHERING LOCOMOTION DAVID L. HU() AND MICHAEL SHELLEY∗∗ Abstract. Limbless terrestrial animals propel themselves by sliding their bellies along the ground. Although the study of dry solid-solid friction is a classical subject, the mechanisms underlying friction-based limbless propulsion have received little attention. We review and expand upon our previous work on the locomotion of snakes, who are expert sliders. We show that snakes use two principal mechanisms to slither on flat surfaces. First, their bellies are covered with scales that catch upon ground asperities, providing frictional anisotropy. Second, they are able to lift parts of their body slightly off the ground when moving. This reduces undesired frictional drag and applies greater pressure to the parts of the belly that are pushing the snake forwards. We review a theoretical framework that may be adapted by future investigators to understand other kinds of limbless locomotion. Key words. Snakes, friction, locomotion AMS(MOS) subject classifications. Primary 76Zxx 1. Introduction. Animal locomotion is as diverse as animal form. Swimming, flying and walking have received much attention [1, 9]withthe latter being the most commonly studied means for moving on land (Fig. 1). Comparatively little attention has been paid to limbless locomotion on land, which necessarily relies upon sliding. Sliding is physically distinct from pushing against a fluid and understanding it as a form of locomotion presents new challenges, as we present in this review. Terrestrial limbless animals are rare. Those that are multicellular include worms, snails and snakes, and account for less than 2% of the 1.8 million named species (Fig. -

A NOVEL GAIN of FUNCTION of the <I>IRX1</I> and <I>IRX2</I> GENES DISRUPTS AXIS ELONGATION in the ARAUCA

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 8-2013 A NOVEL GAIN OF FUNCTION OF THE IRX1 AND IRX2 GENES DISRUPTS AXIS ELONGATION IN THE ARAUCANA RUMPLESS CHICKEN Nowlan Freese Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Part of the Developmental Biology Commons Recommended Citation Freese, Nowlan, "A NOVEL GAIN OF FUNCTION OF THE IRX1 AND IRX2 GENES DISRUPTS AXIS ELONGATION IN THE ARAUCANA RUMPLESS CHICKEN" (2013). All Dissertations. 1198. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1198 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A NOVEL GAIN OF FUNCTION OF THE IRX1 AND IRX2 GENES DISRUPTS AXIS ELONGATION IN THE ARAUCANA RUMPLESS CHICKEN A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Biological Sciences by Nowlan Hale Freese August 2013 Accepted by: Dr. Susan C. Chapman, Committee Chair Dr. Lesly A. Temesvari Dr. Matthew W. Turnbull Dr. Leigh Anne Clark Dr. Lisa J. Bain ABSTRACT Caudal dysplasia describes a range of developmental disorders that affect normal development of the lumbar spinal column, sacrum and pelvis. An important goal of the congenital malformation field is to identify the genetic mechanisms leading to caudal deformities. To identify the genetic cause(s) and subsequent molecular mechanisms I turned to an animal model, the rumpless Araucana chicken breed. Araucana fail to form vertebrae beyond the level of the hips. -

Snake Skeletonizing Manual

Snake Skeletonizing Manual By Ellen Kuo Illustrations by Omar Malik, Juliana Olsson, and Sara Brenner © 2020 Museum of Vertebrate Zoology Table of Contents Snake anatomy reference images …………………………………………………. Page 2-3 Station setup …………………………………………………. Page 4 Initial data collection and setup …………………………………………………. Page 5-8 Taking photos …………………………………………………. Page 9 Initially determining the sex ………………………………………………… Page 9-10 Skinning …………………………………………………. Page 11-12 Opening and sexing …………………………………………………. Page 13-24 Examples of male gonads …………………………………………………. Page 14-16 Examples of female gonads …………………………………………………... Page 17-23 Taking tissues …………………………………………………. Page 25 Stomach contents, parasites …………………………………………………. Page 25 Finishing and cleaning up …………………………………………………. Page 26 1 Snake Anatomy References 2 Illustration by Sara Brenner Snake skeleton – note that the ribs go down the whole length of the body (they end at the vent, and then the tail does not have ribs). Illustration by Sara Brenner Most snake skulls consist of many small, delicate bones that are unfused. The lower jaw is not fused at the center, allowing the snake to use its lower jaws like arms to slowly feed in prey. Snakes have very sharp, delicate teeth, and lots, and lots, and lots of them — typically on several different jaw bones! Avoid disturbing the teeth. 3 Station Setup Materials ● Snake ● Original data ● Skeleton tag ● Gloves ● Worksheet ● Micron pen ● Forceps ● Scissors (large and small) ● Tray (optional) ● Camera* ● Ruler and/or measuring tape ● Tissue vial ● Vial pen* ● MVZ barcode (for tissue vial) ● Paper towel labeled with H, L, M, K ● Prep Lab Catalog* ● Extra paper towels (optional) ● Scale* ● Herp field guide (for local animals)* ● Probe ● Biohazard bin* *shared materials with the rest of the class 4 Before you start cutting ● Set up your station with all of the listed materials (or access to them) ● Identify the genus and species of your specimen, double checking with the class coordinator to make sure it is correct. -

Kansas Herpetological Society Newsletter No. 54 December, 1983

KANSAS HERPETOLOGICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER NO. 54 DECEMBER, 1983 1984 KHS DUES DUE, DO ... In this issue of the KHS Newsletter, you should find the nifty return-by-mail envelope for payment of your 1984 Kansas Herpetological Society dues. Since your dues are what finances this newsletter, prompt payment is appreciated. If you have already paid your 1984 dues, pass the envelope on to a friend who would like to JO~n the Kansas Herpetological Society. Of all the Regional Herpetological Societies in the U.S . , the KHS has some of the LO\fEST membership rates. If you are missing your dues envelope, or have lost it, the rates are still as follows: Regular member (U.S . ) $4.00 Non-U .S. member $8.00 Contributing member $15.00 Make your checks or money orders payable to KHS. Be sure that your CORRECT mailing address is printed neatly on the outside of the envelope. Send your money to: Kansas Herpetological Society Museum of Natural History University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 66045 KHS NEWSLETTER NO. 54 1 ANNOUNCENENTS Who Are Those Herpetologists, Anyway? If you are in the mood to expand your Christmas card list, here is a chance to get the names and addresses of over 2,000 professional and amateur herpetologists, plus lots of other neat stuff. The Silver Anniversary Membership Directory of the Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles has just been published and also contains a list of herpetological societies and organizations of the world (organized by country, each listing includes an address to write to and usually a list of publications) , a brief history of the SSAR, and other useful information about the SSAR and its organization. -

CNN-Based Genetic Algorithm

International Journal of Computational Intelligence Systems, Vol.2, No. 2 (June, 2009), 124-131 Cellular Neural Networks-Based Genetic Algorithm for Optimizing the Behavior of an Unstructured Robot Alireza Fasih Transportation Informatics Group, Institute of Smart Systems Technologies, University of Klagenfurt Klagenfurt, Austria E-mail: [email protected] Jean Chamberlain Chedjou Transportation Informatics Group, Institute of Smart Systems Technologies, University of Klagenfurt E-mail: [email protected] Kyandoghere Kyamakya Transportation Informatics Group, Institute of Smart Systems Technologies, University of Klagenfurt E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A new learning algorithm for advanced robot locomotion is presented in this paper. This method involves both Cellular Neural Networks (CNN) technology and an evolutionary process based on genetic algorithm (GA) for a learning process. Learning is formulated as an optimization problem. CNN Templates are derived by GA after an optimization process. Through these templates the CNN computation platform generates a specific wave leading to the best motion of a walker robot. It is demonstrated that due to the new method presented in this paper an irregular and even a disjointed walker robot can successfully move with the highest performance. Keywords: Cellular Neural Networks, Robot locomotion, Simulation, Genetic Algorithms. 1. Introduction of animal walking motion with the aim of optimizing the energy consumption [2-4]. It is well-known that the Nowadays, some of the main goals of robotics science, walking motion of animals is of a stereotype. In a large mechatronics and artificial intelligence lie in designing variety of animals a central neural controller does mechanisms close to or mimicking as good as possible organize/coordinate the motion. -

Muscular Mechanisms and Kinematics of Rectilinear Locomotion in Boa Constrictors Steven J

© 2018. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2018) 221, jeb166199. doi:10.1242/jeb.166199 RESEARCH ARTICLE Crawling without wiggling: muscular mechanisms and kinematics of rectilinear locomotion in boa constrictors Steven J. Newman and Bruce C. Jayne* ABSTRACT how such animals coordinate the muscle activity and movement A central issue for understanding locomotion of vertebrates is how among all of these serially homologous structures. Within muscle activity and movements of their segmented axial structures are vertebrates, both lampreys and snakes have body segments with coordinated, and snakes have a longitudinal uniformity of body size and shape that are relatively uniform along most of their length, segments and diverse locomotor behaviors that are well suited for and the absence of appendages provides a somewhat simplified studying the neural control of rhythmic axial movements. Unlike all body plan that makes both of these groups well suited for studying other major modes of snake locomotion, rectilinear locomotion does the neural control of rhythmic axial movements (Cohen, 1988). not involve axial bending, and the mechanisms of propulsion and Furthermore, snakes use different modes of locomotion in a variety modulating speed are not well understood. We integrated of environments, which facilitates investigating the diversity and electromyograms and kinematics of boa constrictors to test plasticity of axial motor patterns. Lissmann’s decades-old hypotheses of activity of the Most previous studies recognize at least four major modes of costocutaneous superior (CCS) and inferior (CCI) muscles and the terrestrial snake locomotion (Mosauer, 1932; Gray, 1968; Gans, intrinsic cutaneous interscutalis (IS) muscle during rectilinear 1974; Jayne, 1986; Cundall, 1987), but rectilinear is the only one of locomotion. -

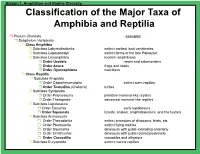

Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia

Station 1. Amphibian and Reptile Diversity Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia ! Phylum Chordata examples ! Subphylum Vertebrata ! Class Amphibia ! Subclass Labyrinthodontia extinct earliest land vertebrates ! Subclass Lepospondyli extinct forms of the late Paleozoic ! Subclass Lissamphibia modern amphibians ! Order Urodela newts and salamanders ! Order Anura frogs and toads ! Order Gymnophiona caecilians ! Class Reptilia ! Subclass Anapsida ! Order Captorhinomorpha extinct stem reptiles ! Order Testudina (Chelonia) turtles ! Subclass Synapsida ! Order Pelycosauria primitive mammal-like reptiles ! Order Therapsida advanced mammal-like reptiles ! Subclass Lepidosaura ! Order Eosuchia early lepidosaurs ! Order Squamata lizards, snakes, amphisbaenians, and the tuatara ! Subclass Archosauria ! Order Thecodontia extinct ancestors of dinosaurs, birds, etc ! Order Pterosauria extinct flying reptiles ! Order Saurischia dinosaurs with pubis extending anteriorly ! Order Ornithischia dinosaurs with pubis rotated posteriorly ! Order Crocodilia crocodiles and alligators ! Subclass Euryapsida extinct marine reptiles Station 1. Amphibian Skin AMPHIBIAN SKIN Most amphibians (amphi = double, bios = life) have a complex life history that often includes aquatic and terrestrial forms. All amphibians have bare skin - lacking scales, feathers, or hair -that is used for exchange of water, ions and gases. Both water and gases pass readily through amphibian skin. Cutaneous respiration depends on moisture, so most frogs and salamanders are -

Alexander 2013 Principles-Of-Animal-Locomotion.Pdf

.................................................... Principles of Animal Locomotion Principles of Animal Locomotion ..................................................... R. McNeill Alexander PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD Copyright © 2003 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY All Rights Reserved Second printing, and first paperback printing, 2006 Paperback ISBN-13: 978-0-691-12634-0 Paperback ISBN-10: 0-691-12634-8 The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition of this book as follows Alexander, R. McNeill. Principles of animal locomotion / R. McNeill Alexander. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ). ISBN 0-691-08678-8 (alk. paper) 1. Animal locomotion. I. Title. QP301.A2963 2002 591.47′9—dc21 2002016904 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Galliard and Bulmer Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ pup.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America 1098765432 Contents ............................................................... PREFACE ix Chapter 1. The Best Way to Travel 1 1.1. Fitness 1 1.2. Speed 2 1.3. Acceleration and Maneuverability 2 1.4. Endurance 4 1.5. Economy of Energy 7 1.6. Stability 8 1.7. Compromises 9 1.8. Constraints 9 1.9. Optimization Theory 10 1.10. Gaits 12 Chapter 2. Muscle, the Motor 15 2.1. How Muscles Exert Force 15 2.2. Shortening and Lengthening Muscle 22 2.3. Power Output of Muscles 26 2.4. Pennation Patterns and Moment Arms 28 2.5. Power Consumption 31 2.6. Some Other Types of Muscle 34 Chapter 3. -

Studies on Amphisbaenids

STUDIES ON AMPHISBAENIDS (AMPHISBAENJA, REPTILIA) 1. A TAXONOMIC REVISION OF THE TROGONOPHINAE, AND A FUNC- TIONAL INTERPRETATION OF THE AMPHISBAENID ADAPTIVE PATTERN CARL GANS BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY VOLUME 119 : ARTICLE 3 NEW YORK: 1960 STUDIES ON AMPHISBAENIDS (AMPHISBAENIA, REPTILIA) STUDIES ON AMPHISBAENIDS (AMPHISBAENIA, REPTILIA) 1. A TAXONOMIC REVISION OF THE TROGONOPHINAE, AND A FUNCTIONAL INTERPRETATION OF THE AMPHIS- BAENID ADAPTIVE PATTERN CARL GANS Research Associate, Department of Amphibians and Reptiles The American Museum of Natural History Department of Biology, The University of Buffalo Buffalo, New York Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY VOLUME 119 : ARTICLE 3 NEW YORK 1960 BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Volume 119, article 3, pages 129-204, text figures 1-32, plate 45, tables 1-3 Issued May 23, 1960 Price: $1.50 a copy CONTENTS INTRODUCTION. * * * 4 135 A TAXONOMIC REVISION OF THE TROGONOPHINAE * . * * * * * 136 Material. * . * * * - 136 Discussion of Characters. * . * * * * 139 Shape and Scutellation of Head. * . X 139 Diplometopon. * . * . - 139 Other Acrodont Forms. * * * * 141 Posterior Integument ............. * . * * . * . 141 Diplometopon. ****** * . o* * * * * 141 Other Acrodont Forms. * * * * 144 Color Pattern ................ * * * * * * . * . 146 Skull. *. s* * * * * 147 General Comparison ............ * * * * * . * @ 147 Trogonophis. * . * * * * 149 Pachycalamus. * . * . e 153 *****. *- * * * - Diplometopon. -

Special Feature on Bio-Inspired Robotics

applied sciences Editorial Special Feature on Bio-Inspired Robotics Toshio Fukuda 1,2,3, Fei Chen 4,* ID and Qing Shi 3 1 Institute for Advanced Research, Nagoya University, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya 464-8601, Japan; [email protected] 2 Department of Mechatronics Engineering, Meijo University, Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture 468-0073, Japan 3 Intelligent Robotics Institute, School of Mechatronic Engineering, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing 100081, China; [email protected] 4 Department of Advanced Robotics, Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Via Morego 30, 16163 Genoa, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-10-71781-217 Received: 4 May 2018; Accepted: 14 May 2018; Published: 18 May 2018 1. Introduction Modern robotic technologies have enabled robots to operate in a variety of unstructured and dynamically-changing environments, in addition to traditional structured environments. Robots have, thus, become an important element in our everyday lives. One key approach to develop such intelligent and autonomous robots is to draw inspiration from biological systems. Biological structure, mechanisms, and underlying principles have the potential to feed new ideas to support the improvement of conventional robotic designs and control. Such biological principles usually originate from animal or even plant models for robots, which can sense, think, walk, swim, crawl, jump or even fly. Thus, it is believed that these bio-inspired methods are becoming increasingly important in the face of complex applications. Bio-inspired robotics is leading to the study of innovative structures and computing with sensory-motor coordination and learning to achieve intelligence, flexibility, stability, and adaptation for emergent robotic applications, such as manipulation, learning, and control. -

Getting It Straight: Accommodating Rectilinear Behavior in Captive Snakes—A Review of Recommendations and Their Evidence Base

animals Article Getting It Straight: Accommodating Rectilinear Behavior in Captive Snakes—A Review of Recommendations and Their Evidence Base Clifford Warwick 1,*, Rachel Grant 2, Catrina Steedman 1, Tiffani J. Howell 3 , Phillip C. Arena 4, Angelo J. L. Lambiris 1, Ann-Elizabeth Nash 5, Mike Jessop 6, Anthony Pilny 7, Melissa Amarello 8 , Steve Gorzula 9, Marisa Spain 10, Adrian Walton 11, Emma Nicholas 12, Karen Mancera 13, Martin Whitehead 14 , Albert Martínez-Silvestre 15 , Vanessa Cadenas 16, Alexandra Whittaker 17 and Alix Wilson 18 1 Emergent Disease Foundation, Suite 114, 80 Churchill Square Business Centre, King’s Hill, Kent ME19 4YU, UK; [email protected] (C.S.); [email protected] (A.J.L.L.) 2 School of Applied Sciences, London South Bank University, 103 Borough Rd, London SE1 0AA, UK; [email protected] 3 School of Psychology and Public Health, La Trobe University, Bendigo, VIC 3552, Australia; [email protected] 4 Pro-Vice Chancellor (Education) Department, Murdoch University, Mandurah, WA 6210, Australia; [email protected] 5 Colorado Reptile Humane Society, 13941 Elmore Road, Longmont, Colorado, CO 80504, USA; [email protected] 6 Veterinary Expert, P.O. Box 575, Swansea SA8 9AW, UK; [email protected] 7 Arizona Exotic Animal Hospital, 2340 E Beardsley Road Ste 100, Phoenix, Arizona, AZ 85024, USA; [email protected] 8 Advocates for Snake Preservation, P.O. Box 2752, Silver City, NM 88062, USA; [email protected] Citation: Warwick, C.; Grant, R.; 9 Freelance Consultant, 7724 Glenister Drive, Springfield, VA 22152, USA; [email protected] Steedman, C.; Howell, T.J.; Arena, 10 Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens, 370 Zoo Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32218, USA; [email protected] P.C.; Lambiris, A.J.L.; Nash, A.-E.; 11 Dewdney Animal Hospital, 11965 228th Street, Maple Ridge, BC V2X 6M1, Canada; [email protected] Jessop, M.; Pilny, A.; Amarello, M.; 12 Notting Hill Medivet, 106 Talbot Road, London W11 1JR, UK; [email protected] et al.