The Status of Vlad Tepes in Communist Romania: a Reassessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONSTITUȚIE*) Din 21 Noiembrie 1991 (*Republicată*) EMITENT PARLAMENTUL Publicat În MONITORUL OFICIAL Nr

CONSTITUȚIE*) din 21 noiembrie 1991 (*republicată*) EMITENT PARLAMENTUL Publicat în MONITORUL OFICIAL nr. 767 din 31 octombrie 2003 Notă *) Modificată și completată prin Legea de revizuire a Constituției României nr. 429/2003, publicată în Monitorul Oficial al României, Partea I, nr. 758 din 29 octombrie 2003, republicată de Consiliul Legislativ, în temeiul art. 152 din Constituție, cu reactualizarea denumirilor și dându-se textelor o noua numerotare (art. 152 a devenit, în forma republicată, art. 156). Legea de revizuire a Constituției României nr. 429/2003 a fost aprobată prin referendumul național din 18-19 octombrie 2003 și a intrat în vigoare la data de 29 octombrie 2003, data publicării în Monitorul Oficial al României, Partea I, nr. 758 din 29 octombrie 2003 a Hotărârii Curții Constituționale nr. 3 din 22 octombrie 2003 pentru confirmarea rezultatului referendumului național din 18-19 octombrie 2003 privind Legea de revizuire a Constituției României. Constituția României, în forma inițială, a fost adoptată în ședința Adunării Constituante din 21 noiembrie 1991, a fost publicată în Monitorul Oficial al României, Partea I, nr. 233 din 21 noiembrie 1991 și a intrat în vigoare în urma aprobării ei prin referendumul național din 8 decembrie 1991. Titlul I Principii generale Articolul 1 Statul român (1) România este stat național, suveran și independent, unitar și indivizibil. (2) Forma de guvernamant a statului român este republica. (3) România este stat de drept, democratic și social, în care demnitatea omului, drepturile și libertățile cetățenilor, libera dezvoltare a personalității umane, dreptatea și pluralismul politic reprezintă valori supreme, în spiritul traditiilor democratice ale poporului român și idealurilor Revoluției din decembrie 1989, și sunt garantate. -

01:510:255:90 DRACULA — FACTS & FICTIONS Winter Session 2018 Professor Stephen W. Reinert

01:510:255:90 DRACULA — FACTS & FICTIONS Winter Session 2018 Professor Stephen W. Reinert (History) COURSE FORMAT The course content and assessment components (discussion forums, examinations) are fully delivered online. COURSE OVERVIEW & GOALS Everyone's heard of “Dracula” and knows who he was (or is!), right? Well ... While it's true that “Dracula” — aka “Vlad III Dracula” and “Vlad the Impaler” — are household words throughout the planet, surprisingly few have any detailed comprehension of his life and times, or comprehend how and why this particular historical figure came to be the most celebrated vampire in history. Throughout this class we'll track those themes, and our guiding aims will be to understand: (1) “what exactly happened” in the course of Dracula's life, and three reigns as prince (voivode) of Wallachia (1448; 1456-62; 1476); (2) how serious historians can (and sometimes cannot!) uncover and interpret the life and career of “The Impaler” on the basis of surviving narratives, documents, pictures, and monuments; (3) how and why contemporaries of Vlad Dracula launched a project of vilifying his character and deeds, in the early decades of the printed book; (4) to what extent Vlad Dracula was known and remembered from the late 15th century down to the 1890s, when Bram Stoker was writing his famous novel ultimately entitled Dracula; (5) how, and with what sources, Stoker constructed his version of Dracula, and why this image became and remains the standard popular notion of Dracula throughout the world; and (6) how Dracula evolved as an icon of 20th century popular culture, particularly in the media of film and the novel. -

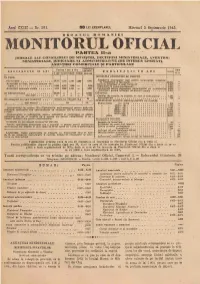

Monitorul Oficial Dill a Dotta Zi

Anul CXIII Nr. 201. 00 LEI EXEMPLARUL illiereurl 5 Septemvrie 1945. 11. REUATHL ROMANIEI MONITORULPARTEA ElaL OFICIAL JURNALE .ALE CONSILIULUI DE MINISTRI, DECIZIUNI MINISTERIALE, ANUNTUR1 MINISTERIALE, JUDICIARE SI ADMINISTRATIVE (DE INTERES LIMITAT), ANUNTURI COMERCIALE SI PARTICULARE 101form. flesbatarile Partea I sari a II-a LINIA ABONAMENTE IN LEI parlament. PUBLICATII IN LE/ laser* 0. ..... 1 anIsIunhI3IunhIlIunäl sesiune IN TARA: JURNALELE CONSILIULUI DE MINISTRI Particulari 10 0005.000 2.500 1.200 6.000 Acordarea avantajelor legii pentru incurajarea industriei la industriasii fabricanti 20.000 Autoritati de Stat, judet si comune ur- Idem la meseriasi si mori tam-most! 4.030 bane 8.000 4.000 2.000 MOO 6.000 Schimbäri de nume, incetäteniri 8 000 .Autorltitti comunale rurale 4.000 2.000 1.000 6.090 Conannicate pentru depunerea juritmfintului de incetatenire8.000 AutorizAri pentru inflintari de birouri vamale ....... 5.000 IN STRAINATATE I 25.000 . 1 12.000 CITATIILE: tine lunri am= mf On. 2.500 Curtilor de Casatle, de Conturi, de Apeii tribunalelor 1.500 Judedttoriilor 750 50 part. I-a60 part. ll-a so Un exemplar din anul curent loi PUBLICATIILE PENTRU AMENAJAMENTE DE PADURI: too ff es anti trecuti Ptiduri intro 0 10 ha 800 PM... 20 1 900 Abonarnentul la partea Ill-a (Desbaterile parlamentare) pentru sesitmile If « 20,01 100 2 500 Ordinare, prelttngite sau extraordinaro se socoteste 1.200 lei lunar (minimum 100,01 200 10 000 I lunä). 200,01 509 15.000 Abonamentele si 131:Mica-title, pentru autoritAtl siparticulari se platesc 7, 500,01-1000 25.000 anticipat. Ele vor fiInsotite de o adresti din partea autoritritilor si de o peste 1009 30 000 cerere timbratil din partea particularilor. -

Judicial Corruption in Eastern Europe: an Examination of Causal Mechanisms in Albania and Romania Claire M

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current Honors College Spring 2017 Judicial corruption in Eastern Europe: An examination of causal mechanisms in Albania and Romania Claire M. Swinko James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019 Part of the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Swinko, Claire M., "Judicial corruption in Eastern Europe: An examination of causal mechanisms in Albania and Romania" (2017). Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current. 334. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019/334 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Judicial Corruption in Eastern Europe: An Examination of Causal Mechanisms in Albania and Romania _______________________ An Honors Program Project Presented to the Faculty of the Undergraduate College of Arts and Letters James Madison University _______________________ by Claire Swinko May 2017 Accepted by the faculty of the Department of Political Science, James Madison University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors Program. FACULTY COMMITTEE: HONORS PROGRAM APPROVAL: Project Advisor: John Hulsey, Ph.D., Bradley R. Newcomer, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Political Science Director, Honors Program Reader: John Scherpereel, Ph.D., Professor, Political Science Reader: Charles Blake, Ph. D., Professor, Political Science Dedication For my dad, who supports and inspires me everyday. You taught me to shoot for the stars, and I would not be half the person I am today with out you. -

When Was Dracula First Translated Into Romanian?

When was Dracula first translated into Romanian? Duncan Light [Duncan Light is Associate Professor in the Department of Geography, Liverpool Hope University. He is currently investigating the way that Romania has responded to Western interest in Dracula over the past four decades.] Introduction Dracula is one of the world’s best-known books. The novel has never been out of print since its publication and has been translated into about 30 languages (Melton). Yet, paradoxically, one of the countries where it is least known is Romania. The usual explanation given for this situation is Romania’s recent history, particularly the period of Communist Party rule (1947-1989). Dracula, with its emphasis on vampires and the supernatural, was apparently regarded as an unsuitable or inappropriate novel in a state founded on the materialist and “scientific” principles of Marxism. Hence, no translation of Stoker’s novel was permitted during the Communist period, a fact noted by several contemporary commentators (for example, Mackenzie 20; Florescu and McNally, Prince 220). As a result, Romania was entirely unprepared for the explosion in the West of popular interest in Dracula and vampires during the 1970s. While increasing numbers of Western tourists visited Transylvania on their own searches for the literary and supernatural roots of Bram Stoker’s novel, they frequently returned disappointed since hardly anybody in Romania understood what they were searching for. For example, Romanian guides and interpreters working for the national tourist office were often bewildered when asked by Western tourists for more details about Dracula and vampires in Romania (Nicolae Păduraru, personal interview). -

Bram Stoker's Vampire Trap : Vlad the Impaler and His Nameless Double

BRAM STOKER’S VAMPIRE TRAP VLAD THE IMPALER AND HIS NAMELEss DOUBLE BY HANS CORNEEL DE ROOS, MA MUNICH EMAIL: [email protected] HOMEPAGE: WWW.HANSDEROOS.COM PUBLISHED BY LINKÖPING UNIVERSITY ELECTRONIC PREss S-581 83 LINKÖPING, SWEDEN IN THE SERIES: LINKÖPING ELECTRONIC ARTICLES IN COMPUTER AND INFORMATION SCIENCE SERIES EDITOR: PROF. ERIK SANDEWALL AbsTRACT Since Bacil Kirtley in 1958 proposed that Bram Stoker’s Count Dracula, the best known literary character ever, shared his historical past with the Wallachian Voivode Vlad III Dracula, an intense debate about this connection has developed and other candidates have been suggested, like the Hungarian General János Hunyadi – a proposal resurfacing in the most recent annotated Dracula edition by Leslie Klinger (2008). By close-reading Stoker’s sources, his research notes and the novel, I will demonstrate that Stoker’s narrative initially links his Count to the person of Vlad III indeed, not Hunyadi, although the novelist neither knew the ruler’s first name, nor his father’s name, nor his epithet “the Impaler”, nor the cruelties attributed to him. Still – or maybe for this very reason – Stoker did not wish to uphold this traceable identity: In Chapter 25, shortly before the decisive chase, he removes this link again, by way of silent substitution, cloaked by Professor van Helsing’s clownish distractions. Like the Vampire Lord Ruthven, disappearing through the “vampire trap” constructed by James R. Planché for his play The Brides of the Isles in the English Opera House, later renamed to Lyceum Theatre and run by Stoker, the historical Voivode Vlad III Dracula is suddenly removed from the stage: In the final chapters, the Vampire Hunters pursue a nameless double. -

Dracula: Hero Or Villain? Radu R

Dracula: Hero or Villain? Radu R. Florescu racula is the real name of a Left: Portrait of Dracula Wallachian ruler, also known to at Castle Ambras, near DRomanian chroniclers as Vlad lnnsbruck, Austria. The the Impaler. Dracula is a derivative of artist is unknown, but his father's name, Dracul, which in this appears to be a Romanian means the devil. According to copy painted during the those more charitably inclined, the second half of the 16th father was so known because he had century from an earlier been invested by the Holy Roman original that was proba Emperor with the Order of the Dragon, bly painted during dedicated to fighting "the Infidel:' Dracula's imprison Dracula was, therefore, either the son of ment at Buda or evil or the son of good, villain or hero. Visegnid after 1462. Dracula ruled the Romanian princi pality of Wallachia on three separate occasions: in 1448, from 1456 to 1462, Right: The Chindia and, briefly, shortly before his assassina watchtower at Tirgo tion in 1476. These dates correspond to vi~te; a 19th-century one of the most crucial periods in the reconstruction. Apart country's history. Constantinople had from its role as an fallen in 1453, most of the lands south of observation post, it Wallachia had been converted into enabled Dracula to Turkish pashaliks, and the last hero of watch impalements in the Balkan crusades, John Hunyadi, had the courtyard below. died in the plague of Belgrade in 1456. Images courtesy The Danube was thus the frontier of Radu R. Florescu Christendom at a time when Moham med the Conqueror was planning fur chronicle which mentions Dracula, dat Genoese, English, and French chroniclers ther Turkish inroads. -

A Tale of Two Visa Regimes: Repercussions of Romania's Accession to the Eu on the Freedom of Movement of Moldovan Citizens

UNISCI DISCUSSION PAPERS Nº 10 (Enero / January 2006) A TALE OF TWO VISA REGIMES: REPERCUSSIONS OF ROMANIA’S ACCESSION TO THE EU ON THE FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT OF MOLDOVAN CITIZENS AUTHOR:1 GEORGE DURA2 Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS), Brussels Introduction In many ways Moldova’s3 efforts to obtain a facilitated visa regime with (future) EU/Schengen states is a case of déjà vu across Europe. Moldova finds itself in the same situation as Russia, Ukraine and certain states of the Western Balkans were in before the 2004 enlargement, prior to becoming direct EU neighbours. Moldova has recently been requesting the EU to open talks on a facilitated regime, not only because Romania’s accession to the EU in 2007 adds a sense of urgency to this issue, but also because neighbouring Ukraine is in the process of negotiating such a facilitated visa regime with the EU. Moldova and Ukraine both signed an Action Plan with the EU in February 2005 as part of the European Neighbourhood Policy. Finally, the Moldovan government would thereby also be able to present its electorate with tangible benefits resulting from the progress towards EU integration. However, so far Moldova’s requests have not yet been granted by the EU. The EU has so far failed to set a date for opening the negotiations on a visa facilitated regime with Moldova. The road towards a facilitated visa regime with EU/Schengen states or new EU member states which are in the process of implementing the Schengen acquis has already been taken by several states, such as Russia, Ukraine or Serbia and Montenegro4. -

The Extreme Right in Contemporary Romania

INTERNATIONAL POLICY ANALYSIS The Extreme Right in Contemporary Romania RADU CINPOEª October 2012 n In contrast to the recent past of the country, there is a low presence of extreme right groups in the electoral competition of today’s Romania. A visible surge in the politi- cal success of such parties in the upcoming parliamentary elections of December 2012 seems to be unlikely. This signals a difference from the current trend in other European countries, but there is still potential for the growth of extremism in Roma- nia aligning it with the general direction in Europe. n Racist, discriminatory and intolerant attitudes are present within society. Casual intol- erance is widespread and racist or discriminatory statements often go unpunished. In the absence of a desire by politicians to lead by example, it is left to civil society organisations to pursue an educative agenda without much state-driven support. n Several prominent members of extreme right parties found refuge in other political forces in the last years. These cases of party migration make it hard to believe that the extreme views held by some of these ex-leaders of right-wing extremism have not found support in the political parties where they currently operate. The fact that some of these individuals manage to rally electoral support may in fact suggest that this happens precisely because of their original views and attitudes, rather than in spite of them. RADU CINPOEª | THE EXTREME RIGHT IN CONTEMPORARY ROMANIA Contents 1. Introduction. 3 2. Extreme Right Actors ...................................................4 2.1 The Greater Romania Party ..............................................4 2.2 The New Generation Party – Christian Democratic (PNG-CD) .....................6 2.3 The Party »Everything for the Country« (TPŢ) ................................7 2.4 The New Right (ND) Movement and the Nationalist Party .......................8 2.5 The Influence of the Romanian Orthodox Church on the Extreme Right Discourse .....8 3. -

Cultural Stereotypes: from Dracula's Myth to Contemporary Diasporic Productions

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Cultural Stereotypes: From Dracula's Myth to Contemporary Diasporic Productions Ileana F. Popa Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1345 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cultural Stereotypes: From Dracula's Myth to Contemporary Diasporic Productions A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. Ileana Florentina Popa BA, University of Bucharest, February 1991 MA, Virginia Commonwealth University, May 2006 Director: Marcel Cornis-Pope, Chair, Department of English Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2006 Table of Contents Page Abstract.. ...............................................................................................vi Chapter I. About Stereotypes and Stereotyping. Definitions, Categories, Examples ..............................................................................1 a. Ethnic stereotypes.. ........................................................................3 b. Racial stereotypes. -

CONTENTS PREFACE by PIERRE GUIRAL Ix FOREWORD Xi INTRODUCTION 1 ONE: DESTINY of the JEWS BEFORE 1866 1

CAROL IANCU – Romanian Jews CONTENTS PREFACE BY PIERRE GUIRAL ix FOREWORD xi INTRODUCTION 1 ONE: DESTINY OF THE JEWS BEFORE 1866 1. Geopolitical Development of Romania 13 2. Origin of the Jews and Their Situation Under the Native Princes 18 3. The Phanariot Regime and the Jews 21 4. The Organic Law and the Beginnings of Legal Anti-Semitism 24 5. 1848: Illusive Promises 27 6. The Jews During the Rebirth of the State (1856-1866) 30 TWO: THE JEWISH PROBLEM BECOMES OFFICIAL 1. Article 7 of the Constitution of 1866 37 2. Bratianu's Circulars and the Consequences Thereof 40 3. Adolphe Crémieux, The Alliance, and Émile Picot 44 4. Sir Moses Montefiore Visits Bucharest 46 THREE: PERSECUTIONS AND INTERVENTIONS (1868-1878) 1. The Disturbances of 1868 and the Draft Law of the Thirty-One and the Great Powers 49 2. The Circulars of Kogalniceanu and Their Consequences 55 3. Riots and Discriminatory Laws 57 4. Bejamin Peixotto's Mission 61 FOUR: FACTORS IN THE RISE OF ANTI-SEMITISM 1. The Religious Factor 68 2. The Economic Factor 70 3. The Political Factor 72 4. The Xenophobic Factor 74 FIVE: PORTRAIT OF THE JEWISH COMMUNITY 1. Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews: Clothing, Language, Names, Habitat, Occupations 77 2. Demographic Evolution 82 3. Disorganization of Community Life 84 4. Isolation and Integration 85 SIX: THE CONGRESS OF BERLIN AND NON-EMANCIPATION 1. Romania and the Jews in the Wings of the Berlin Congress 90 2. Article 44 of the Berlin Treaty 92 3. Emancipation or Naturalization? 94 4. The New Article 7 of the Constitution and Recognition of Romanian Independence 105 SEVEN: ANTI-SEMITIC LEGISLATION 1. -

Nicolae Bănescu 1878

Biblioteca Centrală Universitară „Carol I” - 115 ani de existenţă - Seria: Biobibliografiile Directorilor B.C.U. „Carol I“ din Bucureşti, 3 B i o b i b l i o g r a f i e 1315 referinţe a d n o t a t ă Biblioteca Centrală Universitară „Carol I“ din Bucureşti NicolaeNicolae BănescuBănescu 1878 - 1971 Bucureşti 2010 Lucrare elaborată în cadrul Serviciului Cercetare. Metodologie condus de dr. Dinu Ţenovici R e d a c t o ri Şerban Şubă, Geta Costache, Laura Regneală C o l a b o r a t o r i Elena Bulgaru, Lili Stoicescu, Daniela Stoica, Carmen Goaţă C u l e g e r e t e x t T e h n o r e d a c t a r e Simona Şerban I l u s t r a ţ i i Geta Costache Descrierea CIP a Bibliotecii Naţionale a României N. Bănescu: 1878-1971: biobibliografie adnotată / red.: Şerban Şubă, Geta Costache, Laura Regneală; colab.: Elena Bulgaru, Lili Stoicescu, Daniela Stoica, Carmen Goaţă. – Bucureşti : Biblioteca Centrală Universitară „Carol I“din Bucureşti, 2010 ISBN 978-973-88947-2-3 I. Şubă, Şerban (red.) II. Costache, Geta (red.) III. Regneală, Laura (red.) IV. Bulgaru, Elena V. Stoicescu, Lili VI. Stoica, Daniela VII. Goaţă, Carmen 012:93/94(498) Bănescu, N. 016:93/94(498) Bănescu, N. 929 Bănescu, N. Coperta 1: Nicolae Bănescu, gravură de M. Olarian, 1929 Coperta 4: Fundaţia Universitară Carol I, 1915 ISBN 978-973-88947-2-3 Nicolae Bănescu, director al Bibliotecii Fundaţiei Universitare Carol I între 7 decembrie 1946 şi 9 februarie 1948 C U P R I N S Cuvânt înainte de prof.