Marigolds by Eugenia W. Collier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trinity Cathedr Al Is to Proclaim in Word and Action God’S Justice, Love and Mercy for All Creation

Tr init y Cathedr al NOVEMBER 13, 2016 | FIRST SUNDAY OF ADVENT EARLY EUCHARIST, 8:00 AM (PAGE 4) MOSTLY JAZZ MASS, 9:00 AM (PAGE 7) CHORAL EUCHARIST, 11:15 AM (PAGE 14) THE MISSION OF TRINITY CATHEDR AL IS TO PROCLAIM IN WORD AND ACTION GOD’S JUSTICE, LOVE AND MERCY FOR ALL CREATION. TODAY’S SCRIPTURE READINGS Zephaniah 1:7, 12-18 e silent before the Lord God! For the day of the Lord is at hand; the Lord has prepared a sacrifice, he has consecrated his guests. At that time I will search Jerusalem with lamps, and I will punish Bthe people who rest complacently on their dregs, those who say in their hearts, “The Lord will not do good, nor will he do harm.” Their wealth shall be plundered, and their houses laid waste. Though they build houses, they shall not inhabit them; though they plant vineyards, they shall not drink wine from them. The great day of the Lord is near, near and hastening fast; the sound of the day of the Lord is bit- ter, the warrior cries aloud there. That day will be a day of wrath, a day of distress and anguish, a day of ruin and devastation, a day of darkness and gloom, a day of clouds and thick darkness, a day of trumpet blast and battle cry against the fortified cities and against the lofty battlements. I will bring such distress upon people that they shall walk like the blind; because they have sinned against the Lord, their blood shall be poured out like dust, and their flesh like dung. -

MIDDLE CREEK Wildflower Checklist

PENNSYLVANIA GAME COMMISSION MIDDLE CREEK Wildflower Checklist COMMON NAME FAMILY X HABITAT F M A M J J A S O Agrimony Rose Woods & thickets -- -= == == --- Agrimony, Small-flowered Rose Woods & thickets -- -= == == --- Alfalfa Pea Roadsides & waste places -- -= == =- - Alum Root Saxifrage Woods & rocks - -= == == == -- Amaranth, Green Amaranth Garden weed, poor soil - == == =- Anemone, Rue Buttercup Open woods - == =- Anemone, Wood Buttercup Moist woods - == =- Angelica, Hairy Parsley Dry woods & clearings -= == == =- Arbutus, Trailing Heath Sandy or rocky woods -- == -- Arrowhead, Common Water Plantain Shallow water & marshes -- -= == =- - Arrowhead, Sessile-fruited Water Plantain Shallow water & marshes -- -= == =- - Arrowwood Honeysuckle Woods & borders - -= == == - Asparagus Lily Fields - -= == - Aster, Calico Composite Fields & borders - == == =- Aster, Heart-leaved Composite Woods & thickets - == == =- Aster, Heath Composite Fields, meadows & roadsides - == == =- Aster, Panicled Composite Meadows & shores - == == =- Aster, Purple-stemmed Composite Swamps & low thickets - == == =- Aster, White Wood- Composite Dry woods & clearings - == == =- Avens, White Rose Thickets & open woods -- -= == == --- Azalea, Clammy Heath Swamps -= =- Azalea, Pink Heath Woods & swamps - == =- Baneberry, White Buttercup Woodlands - == =- Bartonia, Yellow Gentian Dry woods & sandy bogs - == - Basil, Wild Mint Woods & borders -- -= == == == Beardtongue, Foxglove Figwort Fields & border of woods - -= == - Bedstraw, Clayton's Madder Swamps & lowgrounds -- -

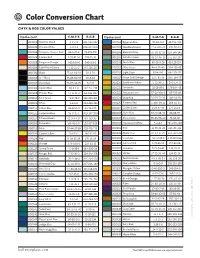

Color Conversion Chart

Color Conversion Chart CMYK & RGB COLOR VALUES Opalescent C-M-Y-K R-G-B Opalescent C-M-Y-K R-G-B 000009 Reactive Cloud 4-2-1-0 241-243-247 000164 Egyptian Blue 81-48-0-0 49-116-184 000013 Opaque White 4-2-2-1 246-247-249 000203 Woodland Brown 22-63-87-49 120-70-29 000016 Turquoise Opaque Rod 65-4-27-6 75-174-179 000206 Elephant Gray 35-30-32-18 150-145-142 000024 Tomato Red 1-99-81-16 198-15-36 000207 Celadon Green 43-14-46-13 141-167-137 000025 Tangerine Orange 1-63-100-0 240-119-2 000208 Dusty Blue 60-25-9-28 83-123-154 000034 Light Peach Cream 5-12-15-0 243-226-213 000212 Olive Green 44-4-91-40 104-133-42 000100 Black 75-66-60-91 10-9-10 000216 Light Cyan 62-4-9-0 88-190-221 000101 Stiff Black 75-66-60-91 10-9-10 000217 Green Gold Stringer 11-6-83-13 206-194-55 000102 Blue Black 76-69-64-85 6-7-13 000220 Sunflower Yellow 5-33-99-1 240-174-0 000104 Glacier Blue 38-3-5-0 162-211-235 000221 Citronelle 35-15-95-1 179-184-43 000108 Powder Blue 41-15-11-3 153-186-207 000222 Avocado Green 57-24-100-2 125-155-48 000112 Mint Green 43-2-49-2 155-201-152 000224 Deep Red 16-99-73-38 140-24-38 000113 White 5-2-5-0 244-245-241 000225 Pimento Red 1-100-99-11 208-10-13 000114 Cobalt Blue 86-61-0-0 43-96-170 000227 Golden Green 2-24-97-34 177-141-0 000116 Turquoise Blue 56-0-21-1 109-197-203 000236 Slate Gray 57-47-38-40 86-88-97 000117 Mineral Green 62-9-64-27 80-139-96 000241 Moss Green 66-45-98-40 73-84-36 000118 Periwinkle 66-46-1-0 102-127-188 000243 Translucent White 5-4-4-1 241-240-240 000119 Mink 37-44-37-28 132-113-113 000301 Pink 13-75-22-10 -

Celebrate the Year of the Marigold

YEAR OF THE MARIGOLD 2018 Celebrate the year Step by Step 1. Sow them thinly into small pots of seed compost from March in a light, frost-free place such as a windowsill or porch. 2. Prick out seedlings singly into small pots or modules of the Marigold filled multi-purpose compost and allow the roots to fill the pot. Plant these easy to grow garden stalwarts for zingy coloured flowers 3. Plant out into their flowering position when all risk of all through the summer. One of the easiest garden annuals to grow, frost has passed. Marigolds are not just vibrant bedding plants they are an excellent choice 4. Feed with a high potash feed for flowering plants. for pots and patio gardening too. 5. Deadhead regularly to keep the plants flowering. SUN WORSHIPERS • Choose to grow Marigolds for • Grow compact French Marigolds in • Marigolds are part of the daisy their reliable production of flowers hanging baskets for a sunny, bright family and originate from north, from late spring into autumn. and colourful display at the front door. central and south America where • Marigold flowers are bright and • Plant taller African Marigolds in they thrive in full sun. They are best beautiful adding glowing shades the middle or towards the back of planted into rich, well-drained soil of yellow, burnt orange and rustic a display to add height, interest in a sunny spot in your garden. reds to your pots, beds and border. and depth to your display. • Marigolds come in a fantastic •Grow single, open flowered marigolds • For a low maintenance container, array of flower shapes, colours to attract butterflies and bees that plant one or three signet Marigolds and plant forms and are ideal will feed on the pollen and nectar. -

African) Marigold Tagetes Erecta and the Smaller-Flowered French Marigold Tagetes Patula (Fig

Fact Sheet FPS-569 October, 1999 Tagetes erecta1 Edward F. Gilman, Teresa Howe2 Introduction There are two basic types of Marigold: the large-flowered American (also referred to as African) Marigold Tagetes erecta and the smaller-flowered French Marigold Tagetes patula (Fig. 1). A less well known species, Tagetes tenuifolia has small flowers and leaves than most other marigolds. Yellow, orange, golden or bicolored flowers are held either well above the fine- textured, dark green foliage or tucked in with the foliage, depending on the cultivar. They brighten up any sunny area in the landscape and attract attention. As flowers die, they hang on the plants and detract from the appearance of the landscape bed. Cut them off periodically to enhance appearance. Marigolds may be used as a dried flower and are planted 10 to 14 inches apart to form a solid mass of color. Some of the taller selections fall over in heavy rain or in windy weather. General Information Scientific name: Tagetes erecta Pronunciation: tuh-JEE-teez ee-RECK-tuh Common name(s): American Marigold, African Marigold Figure 1. American Marigold. Family: Compositae Plant type: annual Availablity: generally available in many areas within its USDA hardiness zones: all zones (Fig. 2) hardiness range Planting month for zone 7: Jun Planting month for zone 8: May; Jun Planting month for zone 9: Mar; Apr; Sep; Oct; Nov Description Planting month for zone 10 and 11: Feb; Mar; Oct; Nov; Dec Height: 1 to 3 feet Origin: native to North America Spread: .5 to 1 feet Uses: container or above-ground planter; edging; cut flowers; Plant habit: upright border; attracts butterflies Plant density: dense 1.This document is Fact Sheet FPS-569, one of a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. -

Millersburg Carnival Glass Auction Friday March 22, 2019 Lots 1-175

Millersburg Carnival Glass Auction Friday March 22, 2019 Lots 1-175 ____1. Imperial Dark Marigold Fashion Punch Base Only. ____24. Northwood Pastel Marigold Leaf & Beads Candy ____2. Northwood Marigold Memphis Punch Base Only. Dish. (Tri-Cornered; Pretty Pastel Iridescence!) (Lots of Pretty Pastel Highlights!) ____25. Northwood Green Leaf and Beads Nut Bowl. (Floral ____3. Northwood Marigold Grape & Cable Punch Base Interior.) Only. (Mid-Size Base.) ____26. NORTHWOOD ELECTRIC BLUE BEADED CABLE ____4. Three Piece Fenton Carnival Lot. (Amethyst Birds ROSEBOWL. (SUPER ATTRACTIVE!) and Cherries Compote, Blue Thistle Bowl with 3/1 ____27. Northwood Amethyst Wishbone ftd. Ruffled Bowl. Edge, Marigold Peacock and Grape Ruffled Bowl.) (Ruffles & Rings Exterior, Nice Example.) ____5. Pair of Carnival Glass Tumblers. (N Electric Blue ____28. Northwood Amethyst Strawberry Plate. (8 3/4" Peacock at the Fountain, and N Pearlized Custard Basketweave Exterior.) Grape & Gothic Arches.) ____29. Pair of Northwood Three Fruits Bowls. (Amethyst ____6. Millersburg Amethyst Peacock at Urn 6" Bowl. (Satin Three Fruits Medallion, and Purple Three Fruits with Finish, Beading with No Bee.) PCE.) ____7. Millersburg Marigold Rays & Ribbons Bowl. (3/1 ____30. Northwood Purple G&C Banana Boat Edge. 10 1/4" Radium and Nice!) ____31. NORTHWOOD WHITE POPPY SHOW RUFFLED ____8. Millersburg Marigold Holly Sprig Bowl. (Ruffled BOWL. (8 3/4" FROSTY IRIDESCENCE.) Crimped Edge with Star Interior, Radium ____32. Four Piece Dugan Carnival Glass Lot. (Peach Opal Iridescence!) Question Marks Stemmed Bon-Bon, Peach Opal ____9. Westmoreland Peach Opal Scales Flared Plate. (8 Pulled Loops Vase, Marigold Target Vase, and 3/4" Nice Opal and Very Flat.) Peach Opal Spiralex Vase.) ____10. -

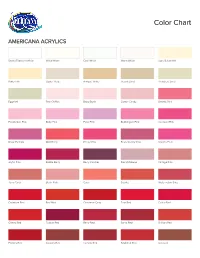

Color Chart Colorchart

Color Chart AMERICANA ACRYLICS Snow (Titanium) White White Wash Cool White Warm White Light Buttermilk Buttermilk Oyster Beige Antique White Desert Sand Bleached Sand Eggshell Pink Chiffon Baby Blush Cotton Candy Electric Pink Poodleskirt Pink Baby Pink Petal Pink Bubblegum Pink Carousel Pink Royal Fuchsia Wild Berry Peony Pink Boysenberry Pink Dragon Fruit Joyful Pink Razzle Berry Berry Cobbler French Mauve Vintage Pink Terra Coral Blush Pink Coral Scarlet Watermelon Slice Cadmium Red Red Alert Cinnamon Drop True Red Calico Red Cherry Red Tuscan Red Berry Red Santa Red Brilliant Red Primary Red Country Red Tomato Red Naphthol Red Oxblood Burgundy Wine Heritage Brick Alizarin Crimson Deep Burgundy Napa Red Rookwood Red Antique Maroon Mulberry Cranberry Wine Natural Buff Sugared Peach White Peach Warm Beige Coral Cloud Cactus Flower Melon Coral Blush Bright Salmon Peaches 'n Cream Coral Shell Tangerine Bright Orange Jack-O'-Lantern Orange Spiced Pumpkin Tangelo Orange Orange Flame Canyon Orange Warm Sunset Cadmium Orange Dried Clay Persimmon Burnt Orange Georgia Clay Banana Cream Sand Pineapple Sunny Day Lemon Yellow Summer Squash Bright Yellow Cadmium Yellow Yellow Light Golden Yellow Primary Yellow Saffron Yellow Moon Yellow Marigold Golden Straw Yellow Ochre Camel True Ochre Antique Gold Antique Gold Deep Citron Green Margarita Chartreuse Yellow Olive Green Yellow Green Matcha Green Wasabi Green Celery Shoot Antique Green Light Sage Light Lime Pistachio Mint Irish Moss Sweet Mint Sage Mint Mint Julep Green Jadeite Glass Green Tree Jade -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Seeck Auction Service HOACGA Special Event Poucher Collection

Seeck Auction Service HOACGA Special Event Auction Gross $771,355.00 Poucher Collection 09/13/2014 9:30 AM Bid # Sold For Lot Description 605 $190.00 1 Provence pitcher - marigold - super pretty, by Inwald 62 $180.00 2 Provence tumbler - marigold - also pretty, by Inwald 664 $350.00 3 Chesterfield compote or cake plate - red stretch - 5 1/2 high, 9 1/2 diam. very stretchy irid., small nick on base 95 $160.00 4 Lacy Dewdrop compote or cake plate - pearlized milk glass 40 $52,500.00 5 Goddess of Harvest CRE bowl - blue- only blue bowl in any shape reported, this is a fantastic rarity, may be a once in a lifetime opportunity, WOW!! 40 $25,000.00 6 Goddess of Harvest CRE bowl - amethyst - yes, 2 of them! again, another rare chance to buy one of the most desired pieces out there 99 $6,000.00 7 Goddess of Harvest ruffled bowl - marigold - no, 3 of them! third time is a charm, one of the most desirable Fenton patterns, very minor no harm nick on base 614 $250.00 8 S-Repeat tumbler - marigold - very rare tumbler, highly desirable and nice 14 $24,000.00 9 Poppy Show 9" plate - aqua opal - beautiful pastel irid. on this extremely rare Northwood plate, a rare chance at a goodie! 49 $650.00 10 Poppy Show 9" plate - ice blue - scarce 22 $180.00 11 Poppy Show 9" plate - blue - electric highlights, base repaired 651 $400.00 12 Poppy Show 9" plate - marigold - dark, very pretty 6 $225.00 13 Poppy Show 9" plate - white - nice 614 $165.00 14 M'burg Hanging Cherries tumbler - green- this has the flared base 614 $160.00 15 M'burg Hanging Cherries tumbler -

Taishan Marigold Earns a Gold Medal in Beijing New Marigold Stands out at 2008 Olympics

Taishan Marigold Earns a Gold Medal in Beijing New Marigold stands out at 2008 Olympics WEST CHICAGO, IL – It took seven years of planning for the Beijing 2008 Olympics, and in the end, Taishan Marigold has earned a gold medal. These Dwarf F1 African marigolds – bred by PanAmerican Seed – stood out among the more than 200 million plants that were used in landscape beds throughout Beijing, and continually thrived throughout the high humidity and extraordinary heat of the summer months. Dr. Shi-Ying Wang, China Commercial Director for PanAmerican Seed, has been working closely on the Beijing Environment Project since 2001. Dr. Wang assisted in training and in providing technical support to the local growers and landscapers. Field trials were held in the summer of 2007 to observe plant performance under the extreme weather conditions. Taishan was a prominent performer in the landscape at Beijing National Stadium, also known as the “Bird’s Nest.” This sensational plant was named after the Taishan Mountains, regarded as preeminent among China’s five sacred mountains. The Taishan Mountains were elected to the “World Heritage List”in 1987 and are recognized as a symbol of power in the Chinese culture. Taishan Marigold is a new introduction that will be available in 2010 to the trade. In Chinese, Taishan means stability, which seems to be very fitting as Taishan Marigolds consistently withstand damage from shipping better than competing African Marigolds. In addition, Taishan offers stronger branching for improved landscape performance and delivers excellent, high-impact color. They are available in three colors: Gold, Yellow, Orange and also a mixture. -

Música Y Marcas En El Branded Content. Sectores, Formatos Y

Musicidad: Música y marcas en el branded content Sectores, formatos y significado (2009-2013) Cande Sánchez Olmos Tesis doctoral Musicidad: Música y marcas en el branded content Sectores, formatos y significado (2009-2013) Autora: Cande Sánchez Olmos Director: Dr. Raúl Rodríguez Ferrándiz Facultad Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales Departamento de Comunicación y Psicología Social Universidad de Alicante Enero 2015 A mis padres, por obrar el milagro, porque no pudisteis ir a la escuela por la situación histórica y social de este país y, sin embargo, depositasteis en mí toda vuestra pasión por el conocimiento. Agradecimientos Mi más sincero agradecimiento al doctor Raúl Rodríguez Ferrándiz, director de este proyecto, por su confianza y buenos consejos, y por compartir su experiencia investigadora, por mostrarme siempre la luz al final del túnel. Siempre de buen humor y siempre resolviendo de forma positiva cualquier duda. Pero sobre todo, gracias por animarme siempre a defender mi concepto: musicidad, por entenderlo y confiar en él. Gracias al doctor Miguel Mera por recibir con ilusión este proyecto en la City University Londres y por abrirme el camino de la investigación de la música popular desde el rigor científico. Gracias por los consejos, la confianza y por potenciar en mí el espíritu crítico. También gracias al doctor Miller por acogerme en sus seminarios de doctorado del Department of Culture & Creative Industries de la misma universidad y por aportar su visión crítica y científica a la investigación. A mis alumnos de la Universidad de Alicante, porque les encanta que les explique sobre música y la publicidad y eso siempre me ha animado a seguir adelante. -

Marigold Perfection™

Perfection™ Yellow Marigold Perfection™ Culture Guide Botanical name: Tagetes erecta Media EC: SME 0.5 to 0.75 mS/cm Product form: Seed Fertilizer: 75–125 ppm N Containers: Quarts, Gallons, Hanging Baskets Moisture level: Media should be allowed to dry between Habit: Upright irrigations. Alternate between moisture level 3 and 4. 2 - MEDIUM: Soil is light brown in color, no water can be Garden Specifications extracted from soil, and soil will crumble apart. Garden Height: 14–16” (35–40 cm) tall 3 - MOIST: Soil is brown in color, strongly squeezing the soil Garden Width: 12–14” (30–35 cm) wide will extract a few drops of water, and trays are light with no Exposure: Full sun visible bend. USDA zone: 10 4 - WET: Soil is dark brown but not shiny, no free water is AHS zone: 12–1 seen at the surface of the soil, when pressed or squeezed Product use: Containers, Hanging Baskets, Landscapes, water drips easily, and trays are heavy with a visible bend in Patio Pots, Combos the middle. Germination Pinching: No Plant growth regulators (PGRs): Usually not Stages 1 & 2 needed. If necessary spray with B-Nine at 1,500–2,500 ppm Germination time: 3–5 days to control stem elongation. Media temp: 72–75 °F (22–24 °C) Plug grow time: 4–5 weeks in a 288-cell tray Chamber: Optional Comments: Easy to germinate on the bench. Maintain Light: Not required for germination media pH above 6.2 to avoid iron/manganese toxicity. Short Seed cover: Yes days will shorten time to flower.