Recurrent Ataxia in Children and Adolescents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Glucose Transport and Glucose Metabolism by Exercise Training

nutrients Review Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Glucose Transport and Glucose Metabolism by Exercise Training Parker L. Evans 1,2,3, Shawna L. McMillin 1,2,3 , Luke A. Weyrauch 1,2,3 and Carol A. Witczak 1,2,3,4,* 1 Department of Kinesiology, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27858, USA; [email protected] (P.L.E.); [email protected] (S.L.M.); [email protected] (L.A.W.) 2 Department of Physiology, Brody School of Medicine, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27834, USA 3 East Carolina Diabetes & Obesity Institute, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27834, USA 4 Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, Brody School of Medicine, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27834, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-252-744-1224 Received: 8 September 2019; Accepted: 8 October 2019; Published: 12 October 2019 Abstract: Aerobic exercise training and resistance exercise training are both well-known for their ability to improve human health; especially in individuals with type 2 diabetes. However, there are critical differences between these two main forms of exercise training and the adaptations that they induce in the body that may account for their beneficial effects. This article reviews the literature and highlights key gaps in our current understanding of the effects of aerobic and resistance exercise training on the regulation of systemic glucose homeostasis, skeletal muscle glucose transport and skeletal muscle glucose metabolism. Keywords: aerobic exercise; blood glucose; functional overload; GLUT; hexokinase; insulin resistance; resistance exercise; SGLT; type 2 diabetes; weightlifting 1. Introduction Exercise training is defined as planned bouts of physical activity which repeatedly occur over a duration of time lasting from weeks to years. -

WES Gene Package Multiple Congenital Anomalie.Xlsx

Whole Exome Sequencing Gene package Multiple congenital anomalie, version 5, 1‐2‐2018 Technical information DNA was enriched using Agilent SureSelect Clinical Research Exome V2 capture and paired‐end sequenced on the Illumina platform (outsourced). The aim is to obtain 8.1 Giga base pairs per exome with a mapped fraction of 0.99. The average coverage of the exome is ~50x. Duplicate reads are excluded. Data are demultiplexed with bcl2fastq Conversion Software from Illumina. Reads are mapped to the genome using the BWA‐MEM algorithm (reference: http://bio‐bwa.sourceforge.net/). Variant detection is performed by the Genome Analysis Toolkit HaplotypeCaller (reference: http://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/). The detected variants are filtered and annotated with Cartagenia software and classified with Alamut Visual. It is not excluded that pathogenic mutations are being missed using this technology. At this moment, there is not enough information about the sensitivity of this technique with respect to the detection of deletions and duplications of more than 5 nucleotides and of somatic mosaic mutations (all types of sequence changes). HGNC approved Phenotype description including OMIM phenotype ID(s) OMIM median depth % covered % covered % covered gene symbol gene ID >10x >20x >30x A4GALT [Blood group, P1Pk system, P(2) phenotype], 111400 607922 101 100 100 99 [Blood group, P1Pk system, p phenotype], 111400 NOR polyagglutination syndrome, 111400 AAAS Achalasia‐addisonianism‐alacrimia syndrome, 231550 605378 73 100 100 100 AAGAB Keratoderma, palmoplantar, -

The Genetic Landscape of the Human Solute Carrier (SLC) Transporter Superfamily

Human Genetics (2019) 138:1359–1377 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-019-02081-x ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION The genetic landscape of the human solute carrier (SLC) transporter superfamily Lena Schaller1 · Volker M. Lauschke1 Received: 4 August 2019 / Accepted: 26 October 2019 / Published online: 2 November 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract The human solute carrier (SLC) superfamily of transporters is comprised of over 400 membrane-bound proteins, and plays essential roles in a multitude of physiological and pharmacological processes. In addition, perturbation of SLC transporter function underlies numerous human diseases, which renders SLC transporters attractive drug targets. Common genetic polymorphisms in SLC genes have been associated with inter-individual diferences in drug efcacy and toxicity. However, despite their tremendous clinical relevance, epidemiological data of these variants are mostly derived from heterogeneous cohorts of small sample size and the genetic SLC landscape beyond these common variants has not been comprehensively assessed. In this study, we analyzed Next-Generation Sequencing data from 141,456 individuals from seven major human populations to evaluate genetic variability, its functional consequences, and ethnogeographic patterns across the entire SLC superfamily of transporters. Importantly, of the 204,287 exonic single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) which we identifed, 99.8% were present in less than 1% of analyzed alleles. Comprehensive computational analyses using 13 partially orthogonal algorithms that predict the functional impact of genetic variations based on sequence information, evolutionary conserva- tion, structural considerations, and functional genomics data revealed that each individual genome harbors 29.7 variants with putative functional efects, of which rare variants account for 18%. Inter-ethnic variability was found to be extensive, and 83% of deleterious SLC variants were only identifed in a single population. -

The Genetic Relationship Between Paroxysmal Movement Disorders and Epilepsy

Review article pISSN 2635-909X • eISSN 2635-9103 Ann Child Neurol 2020;28(3):76-87 https://doi.org/10.26815/acn.2020.00073 The Genetic Relationship between Paroxysmal Movement Disorders and Epilepsy Hyunji Ahn, MD, Tae-Sung Ko, MD Department of Pediatrics, Asan Medical Center Children’s Hospital, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea Received: May 1, 2020 Revised: May 12, 2020 Seizures and movement disorders both involve abnormal movements and are often difficult to Accepted: May 24, 2020 distinguish due to their overlapping phenomenology and possible etiological commonalities. Par- oxysmal movement disorders, which include three paroxysmal dyskinesia syndromes (paroxysmal Corresponding author: kinesigenic dyskinesia, paroxysmal non-kinesigenic dyskinesia, paroxysmal exercise-induced dys- Tae-Sung Ko, MD kinesia), hemiplegic migraine, and episodic ataxia, are important examples of conditions where Department of Pediatrics, Asan movement disorders and seizures overlap. Recently, many articles describing genes associated Medical Center Children’s Hospital, University of Ulsan College of with paroxysmal movement disorders and epilepsy have been published, providing much infor- Medicine, 88 Olympic-ro 43-gil, mation about their molecular pathology. In this review, we summarize the main genetic disorders Songpa-gu, Seoul 05505, Korea that results in co-occurrence of epilepsy and paroxysmal movement disorders, with a presenta- Tel: +82-2-3010-3390 tion of their genetic characteristics, suspected pathogenic mechanisms, and detailed descriptions Fax: +82-2-473-3725 of paroxysmal movement disorders and seizure types. E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Dyskinesias; Movement disorders; Seizures; Epilepsy Introduction ies, and paroxysmal dyskinesias [3,4]. Paroxysmal dyskinesias are an important disease paradigm asso- Movement disorders often arise from the basal ganglia nuclei or ciated with overlapping movement disorders and seizures [5]. -

Downloaded from the App Store and Nucleobase, Nucleotide and Nucleic Acid Metabolism 7 Google Play

Hoytema van Konijnenburg et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis (2021) 16:170 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-021-01727-2 REVIEW Open Access Treatable inherited metabolic disorders causing intellectual disability: 2021 review and digital app Eva M. M. Hoytema van Konijnenburg1†, Saskia B. Wortmann2,3,4†, Marina J. Koelewijn2, Laura A. Tseng1,4, Roderick Houben6, Sylvia Stöckler‑Ipsiroglu5, Carlos R. Ferreira7 and Clara D. M. van Karnebeek1,2,4,8* Abstract Background: The Treatable ID App was created in 2012 as digital tool to improve early recognition and intervention for treatable inherited metabolic disorders (IMDs) presenting with global developmental delay and intellectual disabil‑ ity (collectively ‘treatable IDs’). Our aim is to update the 2012 review on treatable IDs and App to capture the advances made in the identifcation of new IMDs along with increased pathophysiological insights catalyzing therapeutic development and implementation. Methods: Two independent reviewers queried PubMed, OMIM and Orphanet databases to reassess all previously included disorders and therapies and to identify all reports on Treatable IDs published between 2012 and 2021. These were included if listed in the International Classifcation of IMDs (ICIMD) and presenting with ID as a major feature, and if published evidence for a therapeutic intervention improving ID primary and/or secondary outcomes is avail‑ able. Data on clinical symptoms, diagnostic testing, treatment strategies, efects on outcomes, and evidence levels were extracted and evaluated by the reviewers and external experts. The generated knowledge was translated into a diagnostic algorithm and updated version of the App with novel features. Results: Our review identifed 116 treatable IDs (139 genes), of which 44 newly identifed, belonging to 17 ICIMD categories. -

Metabolic Evaluation of Epilepsy: a Diagnostic Algorithm with Focus on Treatable Conditions

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2018 Metabolic Evaluation of Epilepsy: A Diagnostic Algorithm With Focus on Treatable Conditions van Karnebeek, Clara D M ; Sayson, Bryan ; Lee, Jessica J Y ; Tseng, Laura A ; Blau, Nenad ; Horvath, Gabriella A ; Ferreira, Carlos R Abstract: Although inborn errors of metabolism do not represent the most common cause of seizures, their early identification is of utmost importance, since many will require therapeutic measures beyond that of common anti-epileptic drugs, either in order to control seizures, or to decrease the risk of neurode- generation. We translate the currently-known literature on metabolic etiologies of epilepsy (268 inborn errors of metabolism belonging to 21 categories, with 74 treatable errors), into a 2-tiered diagnostic algo- rithm, with the first-tier comprising accessible, affordable, and less invasive screening tests in urineand blood, with the potential to identify the majority of treatable conditions, while the second-tier tests are ordered based on individual clinical signs and symptoms. This resource aims to support the pediatri- cian, neurologist, biochemical, and clinical geneticists in early identification of treatable inborn errors of metabolism in a child with seizures, allowing for timely initiation of targeted therapy with the potential to improve outcomes. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.01016 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-161470 Journal Article Published Version The following work is licensed under a Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License. -

Inborn Errors of Metabolism in Adults: a Diagnostic Approach to Neurological and Psychiatric Presentations

71 2 Inborn Errors of Metabolism in Adults: A Diagnostic Approach to Neurological and Psychiatric Presentations Fanny Mochel, Frédéric Sedel 2.1 Differences Between Paediatric and Adult Phenotypes – 72 2.2 General Approach to IEM In Adulthood – 72 2.3 Specific Approaches to Neuro metabolic Presentations in Adults – 76 References – 89 J.-M. Saudubray et al. (Eds.), Inborn Metabolic Diseases, DOI 10.1007/978-3-662-49771-5_2, © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2016 72 Chapter 2 · Inborn Errors of Metabolism in Adults: A Diagnostic Approach to Neurological and Psychiatric Presentations Late-onset forms of IEM presenting initially in adulthood are of- In addition, some clinical signs are highly suggestive of a ten unrecognised, so that their exact prevalence is unknown [1]. particular IEM or of a particular group of IEM. Some of these Most often they have psychiatric or neurological manifestations, ‘red flags’ are listed in . Table 2.2. 2 including atypical psychosis or depression, unexplained coma, Unfortunately, in many circumstances, highly specific peripheral neuropathy, cerebellar ataxia, spastic paraparesis, de- signs or symptoms are lacking and the presentation is that of mentia, movement disorders and epilepsy [2][3][4][5]. a less specific neurological or psychiatric disorder (epilepsy, Physicians caring for adult patients with IEM are also involved in cognitive decline, psychiatric signs). In such situations, the the management of those with early onset forms who reach diagnostic approach is based on the type of clinical signs, their adulthood. The transfer of such patients from paediatric to adult clinical course (acute, acute-relapsing, with diurnal variations, care raises a number of medical, dietetic and social concerns. -

Anesthetic Management of a Patient with GLUT1 Deficiency Syndrome

[NM-207] Anesthetic management of a patient with GLUT1 Deficiency Syndrome Mecoli M, Pratap J Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center , Cincinnati , OH, USA Introduction: GLUT1 deficiency syndrome is a rare encephalopathy resulting from abnormal glucose transport into the brain. Patients usually present with early-onset seizures, developmental delay, and movement disorder. The hallmark biochemical feature is low glucose concentration in the CSF in the setting of normoglycemia (1). Treatment of GLUT1 deficiency syndrome revolves around a ketogenic diet in order to supply the brain with an alternative fuel source. Here we present the first description of patient with GLUT1 deficiency syndrome undergoing anesthesia and discuss the anesthetic implications of this rare disorder. Case: A 22 month old girl with GLUT1 deficiency syndrome presented for bilateral myringotomy and insertion of ear tubes. Her initial presentation at 7 months of age was with seizures and developmental delay. Neurologic workup revealed a low glucose CSF concentration and genetic testing confirmed a GLUT1 gene defect. The patient was scheduled as a first case start in order to minimize NPO time. She underwent inhalational induction with sevoflurane and was maintained with mask anesthesia. Intranasal fentanyl was given for analgesia. Point of care glucose testing was performed and determined to be within normal limits. The patient tolerated the procedure well, was taking PO in PACU, and resumed her ketogenic diet. She was discharged home in stable condition. Discussion: GLUT1 deficiency syndrome is very rare with fewer than 100 cases being reported in the literature prior to 2007 (1). Nonetheless, this disorder presents unique features that the practicing pediatric anesthesiologist should consider. -

Clinical, Molecular and Genetic Aspects

Gaceta Médica de México. 2016;152 Contents available at PubMed www.anmm.org.mx PERMANYER Gac Med Mex. 2016;152:492-501 www.permanyer.com GACETA MÉDICA DE MÉXICO REVIEW ARTICLE Glucotransporters: clinical, molecular and genetic aspects Roberto de Jesús Sandoval-Muñiz, Belinda Vargas-Guerrero, Luis Javier Flores-Alvarado and Carmen Magdalena Gurrola-Díaz* Health Sciences Campus, University of Guadalajara, Guadalajara, Jal., Mexico Abstract Oxidation of glucose is the major source of obtaining cell energy, this process requires glucose transport into the cell. However, cell membranes are not permeable to polar molecules such as glucose; therefore its internalization is accomplished by transporter proteins coupled to the cell membrane. In eukaryotic cells, there are two types of carriers coupled to the membrane: 1) cotransporter Na+-glucose (SGLT) where Na+ ion provides motive power for the glucose´s internalization, and 2) the glucotransporters (GLUT) act by facilitated diffusion. This review will focus on the 14 GLUT so far described. Despite the structural homology of GLUT, different genetic alterations of each GLUT cause specific clinical entities. Therefore, the aim of this review is to gather the molecular and biochemical available information of each GLUT as well as the particular syndromes and pathologies related with GLUT´s alterations and their clinical approaches. (Gac Med Mex. 2016;152:492-501) Corresponding author: Carmen Magdalena Gurrola-Díaz, [email protected] KEY WORDS: Sugar transport facilitators. GLUT. Glucose transporters. SLC2A. different affinity for carbohydrates1. In eukaryote cells ntroduction I there are two membrane-coupled transporter proteins: 1) Sodium-glucose co-transporters (SGLT), located in Glucose metabolism provides energy to the cell by the small bowel and renal tissue, mainly responsible means of adenosine-5’-triphosphate (ATP) biosynthe- for the absorption and reabsorption of nutrients, and sis, with glycolysis as the catabolic pathway. -

Episodic Ataxias: Faux Or Real?

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Episodic Ataxias: Faux or Real? Paola Giunti 1,*, Elide Mantuano 2 and Marina Frontali 2,* 1 Laboratory of Neurogenetics, Department of Molecular Neuroscience, UCL Institute of Neurology, London WC2N 5DU, UK 2 Laboratory of Neurogenetics, Institute of Translational Pharmacology, National Research Council of Italy, 00133 Rome, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (P.G.); [email protected] (M.F.) Received: 3 August 2020; Accepted: 1 September 2020; Published: 5 September 2020 Abstract: The term Episodic Ataxias (EA) was originally used for a few autosomal dominant diseases, characterized by attacks of cerebellar dysfunction of variable duration and frequency, often accompanied by other ictal and interictal signs. The original group subsequently grew to include other very rare EAs, frequently reported in single families, for some of which no responsible gene was found. The clinical spectrum of these diseases has been enormously amplified over time. In addition, episodes of ataxia have been described as phenotypic variants in the context of several different disorders. The whole group is somewhat confused, since a strong evidence linking the mutation to a given phenotype has not always been established. In this review we will collect and examine all instances of ataxia episodes reported so far, emphasizing those for which the pathophysiology and the clinical spectrum is best defined. Keywords: episodic ataxia; channelopathies; KCNA1; CACNA1A; SLC1A3; PRRT2; FGF14; SCN2A; SLCA1 1. Introduction Episodic Ataxias (EA) are a genetically heterogeneous group of autosomal dominant disorders characterized by attacks of movement incoordination (cerebellar ataxia) of variable duration and frequency, often accompanied by additional ictal and interictal symptoms. -

Download CGT Exome V2.0

CGT Exome version 2. -

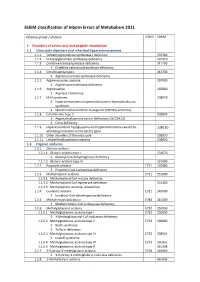

SSIEM Classification of Inborn Errors of Metabolism 2011

SSIEM classification of Inborn Errors of Metabolism 2011 Disease group / disease ICD10 OMIM 1. Disorders of amino acid and peptide metabolism 1.1. Urea cycle disorders and inherited hyperammonaemias 1.1.1. Carbamoylphosphate synthetase I deficiency 237300 1.1.2. N-Acetylglutamate synthetase deficiency 237310 1.1.3. Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency 311250 S Ornithine carbamoyltransferase deficiency 1.1.4. Citrullinaemia type1 215700 S Argininosuccinate synthetase deficiency 1.1.5. Argininosuccinic aciduria 207900 S Argininosuccinate lyase deficiency 1.1.6. Argininaemia 207800 S Arginase I deficiency 1.1.7. HHH syndrome 238970 S Hyperammonaemia-hyperornithinaemia-homocitrullinuria syndrome S Mitochondrial ornithine transporter (ORNT1) deficiency 1.1.8. Citrullinemia Type 2 603859 S Aspartate glutamate carrier deficiency ( SLC25A13) S Citrin deficiency 1.1.9. Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia and hyperammonemia caused by 138130 activating mutations in the GLUD1 gene 1.1.10. Other disorders of the urea cycle 238970 1.1.11. Unspecified hyperammonaemia 238970 1.2. Organic acidurias 1.2.1. Glutaric aciduria 1.2.1.1. Glutaric aciduria type I 231670 S Glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency 1.2.1.2. Glutaric aciduria type III 231690 1.2.2. Propionic aciduria E711 232000 S Propionyl-CoA-Carboxylase deficiency 1.2.3. Methylmalonic aciduria E711 251000 1.2.3.1. Methylmalonyl-CoA mutase deficiency 1.2.3.2. Methylmalonyl-CoA epimerase deficiency 251120 1.2.3.3. Methylmalonic aciduria, unspecified 1.2.4. Isovaleric aciduria E711 243500 S Isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency 1.2.5. Methylcrotonylglycinuria E744 210200 S Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency 1.2.6. Methylglutaconic aciduria E712 250950 1.2.6.1. Methylglutaconic aciduria type I E712 250950 S 3-Methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase deficiency 1.2.6.2.