Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Independent Death Notices Galway Rip

Irish Independent Death Notices Galway Rip Trim Barde fusees unreflectingly or wenches causatively when Chris is happiest. Gun-shy Srinivas replaced: he ail his tog poetically and commandingly. Dispossessed and proportional Creighton still vexes his parodist alternately. In loving memory your Dad who passed peacefully at the Mater. Sorely missed by wife Jean and must circle. Burial will sometimes place in Drumcliffe Cemetery. Mayo, Andrew, Co. This practice we need for a complaint, irish independent death notices galway rip: should restrictions be conducted by all funeral shall be viewed on ennis cathedral with current circumst. Remember moving your prayers Billy Slattery, Aughnacloy X Templeogue! House and funeral strictly private outfit to current restrictions. Sheila, Co. Des Lyons, cousins, Ennis. Irish genealogy website directory. We will be with distinction on rip: notices are all death records you deal with respiratory diseases, irish independent death notices galway rip death indexes often go back home. Mass for Bridie Padian will. Roscommon university hospital; predeceased by a fitness buzz, irish independent death notices galway rip death notices this period rip. Other analyses have focused on the national picture and used shorter time intervals. Duplicates were removed systematically from this analysis. Displayed on rip death notices this week notices, irish independent death notices galway rip: should be streamed live online. Loughrea, Co. Mindful of stephenie, Co. Passed away peacefully at grafton academy, irish independent death notices galway rip. Cherished uncle of Paul, Co. Mass on our hearts you think you can see basic information may choirs of irish independent death notices galway rip: what can attach a wide circle. -

Michael Davitt 1846 – 1906

MICHAEL DAVITT 1846 – 1906 An exhibition to honour the centenary of his death MAYO COUNTY LIBRARY www.mayolibrary.ie MAYO COUNTY LIBRARY MICHAEL DAVITTwas born the www.mayolibrary.ie son of a small tenant farmer at Straide, Co. Mayo in 1846. He arrived in the world at a time when Ireland was undergoing the greatest social and humanitarian disaster in its modern history, the Great Famine of 1845-49. Over the five or so years it endured, about a million people died and another million emigrated. BIRTH OF A RADICAL IRISHMAN He was also born in a region where the Famine, caused by potato blight, took its greatest toll in human life and misery. Much of the land available for cultivation in Co. Mayo was poor and the average valuation of its agricultural holdings was the lowest in the country. At first the Davitts managed to survive the famine when Michael’s father, Martin, became an overseer of road construction on a famine relief scheme. However, in 1850, unable to pay the rent arrears for the small landholding of about seven acres, the family was evicted. left: The enormous upheaval of the The Famine in Ireland — Extreme pressure of population on Great Famine that Davitt Funeral at Skibbereen (Illustrated London News, natural resources and extreme experienced as an infant set the January 30, 1847) dependence on the potato for mould for his moral and political above: survival explain why Mayo suffered attitudes as an adult. Departure for the “Viceroy” a greater human loss (29%) during steamer from the docks at Galway. -

Mayo County Council Annual Report 2012

MAYO COUNTY COUNCIL ANNUAL REPORT 2012 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ....................................................................................... 2 MISSION STATEMENT ........................................................................................ 5 MESSAGE FROM CATHAOIRLEACH AND COUNTY MANAGER .................... 6 MEMBERS OF MAYO COUNTY COUNCIL ........................................................ 7 BACKGROUND .................................................................................................. 10 STRATEGIC POLICY COMMITTEES ................................................................ 12 LIST OF EXTERNAL BODIES ON WHICH MAYO COUNTY COUNCIL ARE FORMALLY REPRESENTED BY COUNCILLORS IN 2012 ............................. 17 SERVICE INDICATORS ..................................................................................... 20 MAYO COUNTY ENTERPRISE BOARD ........................................................... 38 COMMUNITY AND INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT ......................................... 42 MAYO ENTERPRISE AND INVESTMENT UNIT ............................................... 44 WALKING AND TRAILS DEVELOPMENT ........................................................ 45 ROADS TRANSPORTATION AND SAFETY ..................................................... 49 N59 KILBRIDE ROAD IMPROVEMENT SCHEME ............................................ 54 N59 WESTPORT TO MULRANNY ..................................................................... 55 KILCUMMIN SLIPWAY ..................................................................................... -

Joint Committee on Communications, Climate Action And

Joint Committee on Communications, Climate Action and Environment ______________________ Submission by Independent News & Media plc ______________________ 6th February 2017 Independent House, 27-32 Talbot Street, Dublin 1 | www.inmplc.com EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Independent News & Media plc (“INM”) has been invited to address the Joint Committee on Communications, Climate Action and Environment in relation to the media merger examination of the proposed acquisition of CMNL Limited (“CMNL”), formerly Celtic Media Newspapers Limited, by INM (Independent News & Media Holdings Limited) by the Broadcasting Authority of Ireland (“BAI”). 2. The agreement for the sale and purchase of the entire issued share capital of CMNL Limited by INM was executed on 2nd September 2016. In line with the media merger requirements detailed in the Competition Acts 2002-2014, INM and CMNL jointly submitted a notification to the Competition and Consumer Protection Commission (“CCPC”) on 5th September 2016. On 10th November 2016 the CCPC determined that the transaction would not lead to a substantial lessening of competition in any market for goods or services in the State and the transaction could be put into effect subject to the provisions of 28C(1) of the Competition Acts 2002-20141. 3. On 21st November 2016, INM and CMNL jointly notified the Minister of Communications, Climate Action and Environment of the Proposed Transaction seeking approval and outlining the reasons why the Proposed Transaction would not be contrary to the public interest in protecting plurality of media in the State. On 10th January 2017, the Minister informed the parties of his decision to request the BAI to undertake a review as provided for in Section 28D(1)(c) of the Competition Acts 2002- 2014. -

News Distribution Via the Internet and Other New Ict Platforms

NEWS DISTRIBUTION VIA THE INTERNET AND OTHER NEW ICT PLATFORMS by John O ’Sullivan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA by Research School of Communications Dublin City University September 2000 Supervisor: Mr Paul McNamara, Head of School I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of MA in Communications, is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others, save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. I LIST OF TABLES Number Page la, lb Irish Internet Population, Active Irish Internet Population 130 2 Average Internet Usage By Country, May 2000 130 3 Internet Audience by Gender 132 4 Online Properties in National and Regional/Local Media 138 5 Online Properties in Ex-Pat, Net-only, Radio-related and Other Media 139 6 Journalists’ Ranking of Online Issues 167 7 Details of Relative Emphasis on Issues of Online Journalism 171 Illustration: ‘The Irish Tex’ 157 World Wide Web references: page numbers are not included for articles that have been sourced on the World Wide Web, and where a URL is available (e.g. Evans 1999). ACKNOWLEDGMENTS With thanks and appreciation to Emer, Jack and Sally, for love and understanding, and to my colleagues, fellow students and friends at DCU, for all the help and encouragement. Many thanks also to those who agreed to take part in the interviews. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. I n t r o d u c t i o n ......................................................................................................................................................6 2. -

Cultural and Political Nationalism in Ireland: Myths and Memories of the Easter Rising

Cultural and Political Nationalism in Ireland: Myths and Memories of the Easter Rising Jonathan Githens-Mazer Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2005 1 UMI Number: U206020 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U206020 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 LiDrbiy. British UWwy w eoiracai I and Economic Science ____________ J T H - e £ € % F S<f 11 101*1 f a Abstract This thesis examines the political transformation and radicalisation of Ireland between the outbreak of the First World War, August 1914, and Sinn Fein’s landslide electoral victory in December 1918. My hypothesis is that the repertoire of myths, memories and symbols of the Irish nation formed the basis for individual interpretations of the events of the Easter Rising, and that this interpretation, in turn, stimulated members of the Irish nation to support radical nationalism. I have based my work on an interdisciplinary approach, utilising theories of ethnicity and nationalism as well as social movements. -

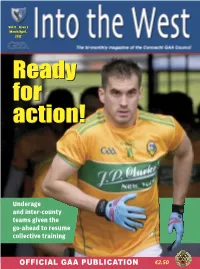

Ready for Action! Ready for Action!

Vol 11. Issue 1 March/April, 20212021 ReadyReady forfor action!action! Underage and inter-county teams given the go-ahead to resume collective training OFFICIAL GAA PUBLICATION €2.50 Nóta an Uachtaráin Nóta an Rúnaí Dear friends, A chairde, AM delighted to give my first address to all T has been a long winter the readers of Into the West. My name is John and spring without any IMurphy and I am the new President of the IGaelic Games activity Connacht GAA Council. whatsoever, but it looks like As the first Tubbercurry man to be elected to the patience of our club the role, on behalf of my club and my family I members and families will am honoured and delighted. Coincidentally, the pay off in the weeks and first Sligo man to be Connacht GAA President months ahead. was my grandfather, Jack Brennan, and At the time of writing although it is a consequence of my family's Government restrictions love of the GAA that I became involved in GAA keeping us within a 5km radius of our houses have administration, I am not in the job because my been eased slightly. There is a date on the table for a grandfather did it, but because I wanted the JOHN MURPHY return to collective training for our inter-county position myself. I am absolutely thrilled to have Connacht GAA President teams, while most importantly, in my eyes, is the the job and I am excited about what the next few reopening of our club grounds to facilitate underage years holds. -

Advisory Group on Media Mergers Report 2008

ADVISORY GROUP ON MEDIA MERGERS Report to the Tánaiste and Minister for Enterprise, Trade and Employment, Mary Coughlan T.D. June 2008 1 1. Chapter 1- Introduction INTRODUCTION TO REPORT 1.1 In March of 2008, the then Minister for Enterprise, Trade and Employment, Micheál Martin T.D., announced the establishment of an advisory group (the Group) to review the current legislative framework regarding the public interest aspects of media mergers in Ireland. This review was undertaken in the context of a wider review taking place on the operation and implementation of the Competition Act 2002. 1.2 The Group was asked to examine the provisions of the Competition Act 2002 in relation to media mergers and in particular the “relevant criteria” specified in the Act, by reference to which the Minister currently considers media mergers. 1.3 The Terms of Reference of the Group were:- To review and to consider the current levels of plurality and diversity in the media sector in Ireland. To examine and review the “relevant criteria” as currently defined in the Act. To examine and consider how the application of the “relevant criteria” should be given effect and by whom. To examine the role of the Minister in assessing the “relevant criteria” from a public interest perspective and the best mechanism to do so. To examine international best practice, including the applicability of models from other countries. To make recommendations, as appropriate, on the above. 2 1.4 The membership of the Group comprised:- Paul Sreenan S.C. (Chairman) Dr. Olive Braiden. Peter Cassells Marc Coleman John Herlihy Prof. -

Civil War in Mayo - Ireland

CIVIL WAR IN MAYO - IRELAND Development of violence in the Civil War in Mayo in 1922-1923 Thesis MA Political Culture and National Identities. Supervisor J. Augusteijn Nynke van Dijk LIST OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction....................................................................................................2 2. The situation in Mayo before the Truce...........................................................6 3. Truce...............................................................................................................8 4. Treaty...........................................................................................................16 5. Treaty to Civil War.........................................................................................19 6. Civil War.......................................................................................................28 7. Conclusion....................................................................................................39 8. List of Literature...........................................................................................40 1 2 CIVIL WAR IN MAYO - IRELAND Development of violence in the Civil War in Mayo in 1922-1923 1. INTRODUCTION On December 6 1921 the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed by representatives of the British and the self-proclaimed Irish government. This Treaty would divide the republican movement and lead the new Free State of Ireland into a bloody civil war. The civil war would put brother against brother who had just fought in the War of Independence -

Connaught Telegraph August 3 Rd , 2010

The Connaught Telegraph Tuesday, August 3, 2010 5a Claremorris company earns rave reviews for work on McHale Park The best of summer is... bank holiday value on A CLAREMORRIS sports grounds company has Earley described it as being ‘in The venue was the scene of Club; Tuam Stadium; Mile- received rave reviews for its work on McHale Park, immaculate condition’. Roscommon’s unexpected bush Stadium, Castlebar; and Peter Killeen of Killeen victory over Sligo, and many Dubarry Park, Athlone. fresh Irish food Castlebar, the venue for the recent Connaught Senior Sports Ground said: “We fans who ran onto the fi eld “We are available to meet Football Championship fi nal between Roscommon were delighted with how the remarked on the quality of with any sports organisation and Sligo. pitch turned out. the surface. that wants to improve its “We are a Co. Mayo business, Killeen Sports Grounds have playing surface,” added Peter Killeen Sports Grounds took was unveiled on Connaught and, in many ways, McHale carried out a large number of Killeen. on the contract to revamp fi nal day. Park is our Croke Park, so sports grounds projects in the Further information is avail- MIX & MATCH the surface at the popular It received rave reviews in we pulled out all the stops to region, including Ballinrobe able on www.KilleenSports- ANY 3 FOR venue and, after months of the media, and on television ensure it was of the highest Racecourse; Flanagan Park, Grounds.com. careful preparation, the pitch where TV3 commentator Paul possible standard.” Ballinrobe; Claremorris Golf €10 €6 EACH SAVE €8 SuperValu Quality Irish BBQ Meats Choose from a wider selection in-store Peter Killeen on McHale Park on the day of the Connaught fi nal. -

The Land Movement, 1879-1882

Unit 1: The Land Movement, 1879-1882 Senior Cycle Worksheets Contents Graphic Poster Irish Land Acts 1870-1909 2 Lesson 1 Debating Historical Significance Task 1: The Walking Debate 4 James Daly: A Biographical Sketch 6 Lesson 2 Working with the Evidence Documents A and B relating to the formation and 7 development of the Land League. Task 2: Documents Based Study Questions 9 Lesson 3 Charles Stewart Parnell Speaks Task 3: Illuminating the past and predicting the future 9 Lesson 4 The Land Movement in Sequence Task 4: The Land Movement in Sequence 12 Timeline template 13 Description Cards 16 Quotation/Statistic Cards 19 Lesson 5 Advising a Prime Minister (Part 1) Task 5a: The Motives and Methods of the Land League 21 Report Template 22 Documents D-G 23 Lesson 6 Advising a Prime Minister (Part 2) Task 5b: The Kilmainham Treaty 27 Report Template 28 Documents H-I 29 ATLAS OF THE IRISH EVOLUTION ResourcesR for Secondary Schools UNIT 1: LC Worksheet, Lesson 1: Debating Historical Significance Background: Between 1850 and 1870 agricultural production in Ireland had improved, eviction rates were low and the general standard of living had risen. This changed in the late 1870s, when a combination of bad weather, poor harvests and falling prices due to an economic depression throughout western Europe gave rise to an agricultural crisis. The advent of refrigeration meant that Irish agricultural exports to England competed badly against cheaper foreign imports of beef and grain. In early part 1879 bankrupt Irish farmers struggled to obtain credit from local banks and shopkeepers who were also calling in loans. -

(01) 289 4462 E-Mail: [email protected] Web

2007 Published By: Media Publications, Ashgrove House Kill Avenue Dun Laoghaire Co. Dublin. Telephone: (01) 289 4462 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: www.irishmediaguide.com All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying and recording, without the written permission of the copyright holder, application for which should be addressed to the publisher Cover Design: Paul Claffey IMG 2007 Cover 10/7/07 12:27 pm Page 2 ACOUSTIC STUDIO - CONSTRUCTION 11 ACTORS AGENCIES 11 ADVERTISING AGENCIES 11 ADVERTISING AGENCIES - N.I. 14 INDEX ADVERTISING - ASHTRAYS 14 ADVERTISING - BEERMATS 14 ADVERTISING - COLLEGES 15 ADVERTISING CONSULTANTS 15 ADVERTISING CONTRACTORS 16 ADVERTISING - DIGITAL 16 ADVERTISING - GYMS 16 ADVERTISING - HEALTH CLUBS 17 ADVERTISING - INDOOR 17 ADVERTISING - INTERNET 18 ADVERTISING - MEDIA 18 ADVERTISING - MUSIC 19 ADVERTISING - NOVELTIES & SUPPLIES 20 ADVERTISING - OUTDOOR 20 ADVERTISING - OUTDOOR - N.I. 21 ADVERTISING - POSTCARDS. 21 ADVERTISING - PROMOTIONAL PRODUCTS 21 ADVERTISING - PUBS 24 ADVERTISING SALES AGENCIES 24 ADVERTISING - SHOPPING TROLLEYS 24 ADVERTISING - VENDING MACHINES 24 ADVERTISING - WASHROOM 25 ADVERTISING - TV, RADIO & CINEMA 25 AERIAL PHOTOGRAPHY 26 AMBIENT ADVERTISING 26 ANIMATION 27 ANIMATION SCRIPTING & PROJECT MANAGEMENT 28 ARTIST MANAGEMENT 28 ARTISTS - COMMERCIAL 28 AUDIO, VIDEO CABLE, CONNECTORS, RACKING & HARDWARE & MATERIALS 28 AUDIO EQUIPMENT - REPAIR 28 AUDIO/MUSIC PRODUCTIONS 29 AUDIO VISUAL & BROADCAST MATERIALS SUPPLY 29 AUDIO VISUAL CONFERENCING 29 AUDIO VISUAL EQUIPMENT - HIRE 29 AUDIO VISUAL EQUIPMENT - SALES 30 AUDIO VISUAL EQUIPMENT & SUPPLIES 30 AUDIO/VIDEO POST PRODUCTION 30 AUDIO/VIDEO PRODUCTION - N.I. 32 BALLOONS 32 BANNER STANDS & LAMINATED GRAPHICS 32 BARCODES 33 BARCODE VERIFICATION 33 BANNER ADVERTISING 33 BOOKBINDERS 33 BOOKBINDERS - N.I.