Civil War in Mayo - Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Éire Go Brách” the Development of Irish Republican Nationalism in the 20Th Into the 21St Centuries

“Éire go Brách” The Development of Irish Republican Nationalism in the 20th into the 21st Centuries Alexandra Watson Honors Thesis Dr. Giacomo Gambino Department of Political Science Spring 2020 Watson 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Literature Review: Irish Nationalism -- What is it ? 5 A Brief History 18 ‘The Irish Question’ and Early Roots of Irish Republicanism 20 Irish Republicanism and the War for Independence 25 The Anglo Irish Treaty of 1921, Pro-Treaty Republicanism vs. Anti-Treaty Republicanism, and Civil War 27 Early Statehood 32 ‘The Troubles’ and the Good Friday Agreement 36 Why is ‘the North’ Different? 36 ‘The Troubles’ 38 The Good Friday Agreement 40 Contemporary Irish Politics: Irish Nationalism Now? 45 Explaining the Current Political System 45 Competing nationalisms Since the Good Friday Agreement and the Possibility of Unification 46 2020 General Election 47 Conclusions 51 Appendix 54 Acknowledgements 57 Bibliography 58 Watson 3 Introduction In June of 2016, the people of the United Kingdom democratically elected to leave the European Union. The UK’s decision to divorce from the European Union has brought significant uncertainty for the country both in domestic and foreign policy and has spurred a national identity crisis across the United Kingdom. The Brexit negotiations themselves, and the consequences of them, put tremendous pressure on already strained international relationships between the UK and other European countries, most notably their geographic neighbour: the Republic of Ireland. The Anglo-Irish relationship is characterized by centuries of mutual antagonism and the development of Irish national consciousness, which ultimately resulted in the establishment of an autonomous Irish free state in 1922. -

Roinn Cosanta

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 624 Witness Mrs. Mary Flannery Woods, 17 Butterfield Crescent, Rathfarnham, Dublin. Identity. Member of A.O.H. and of Cumann na mBan. Subject. Reminiscences of the period 1895-1924. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.1901 Form B.S.M.2 Statement by Mrs. Mary Flannery Woods, 17 Butterfield Crescent, Rathfarnham, Dublin. Memories of the Land League and Evictions. I am 76 years of age. I was born in Monasteraden in County Sligo about five miles from Ballaghaderreen. My first recollections are Of the Lend League. As a little girl I used to go to the meetings of Tim Healy, John Dillon and William O'Brien, and stand at the outside of the crowds listening to the speakers. The substance of the speeches was "Pay no Rent". It people paid rent, organizations such as the "Molly Maguire's" and the "Moonlighters" used to punish them by 'carding them', that means undressing them and drawing a thorny bush over their bodies. I also remember a man, who had a bit of his ear cut off for paying his rent. He came to our house. idea was to terrorise them. Those were timid people who were afraid of being turned out of their holdings if they did not pay. I witnessed some evictions. As I came home from school I saw a family sitting in the rain round a small fire on the side of the road after being turned out their house and the door was locked behind them. -

Making Fenians: the Transnational Constitutive Rhetoric of Revolutionary Irish Nationalism, 1858-1876

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE 8-2014 Making Fenians: The Transnational Constitutive Rhetoric of Revolutionary Irish Nationalism, 1858-1876 Timothy Richard Dougherty Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Modern Languages Commons, and the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dougherty, Timothy Richard, "Making Fenians: The Transnational Constitutive Rhetoric of Revolutionary Irish Nationalism, 1858-1876" (2014). Dissertations - ALL. 143. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/143 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the constitutive rhetorical strategies of revolutionary Irish nationalists operating transnationally from 1858-1876. Collectively known as the Fenians, they consisted of the Irish Republican Brotherhood in the United Kingdom and the Fenian Brotherhood in North America. Conceptually grounded in the main schools of Burkean constitutive rhetoric, it examines public and private letters, speeches, Constitutions, Convention Proceedings, published propaganda, and newspaper arguments of the Fenian counterpublic. It argues two main points. First, the separate national constraints imposed by England and the United States necessitated discursive and non- discursive rhetorical responses in each locale that made -

Military Archives Cathal Brugha Bks Rathmines Dublin 6 ROINN

Military Archives Cathal Brugha BKs Rathmines Dublin 6 ROINN C0SANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 316 Witness Mr. Peter Folan, 134 North Circular Road, Dublin. Identity Head Constable 1913 - 1921. R.I.C. Aided Irish Volunteers and I.R.A. by secret information. Subject (a) Duties as reporter of Irish meetings; (b) Dublin Castle Easter Week 1916 and events from that date to 1921.miscellaneous Conditions, if any, stipulated by Witness Nil File No. S.1431 Form Military Archives Cathal Brugha BKs Rathmines Dublin 6 STATEMENT BY PETER FOLAN (Peadar Mac Fhualáin) Bhothar Thuaidh, 134 Chuar Blá Cliath. I reported several meetings throughout the country. I was always chosen to attend meetings which were likely to be addressed by Irish speakers. Previously, that is from 1908 Onwards, I attended meetings that were addressed by Séamus ó Muilleagha, who was from East Galway and used to travel from County to County as Organiser of the Gaelic League. I was a shorthand reporter and gave verbatim reports of all speakers. Sèamus, in addition to advocating the cause of the language, advised the people that it was a scandal to have large ranches in the possession of one man while there were numbers of poor men without land. He advocated the driving of the cattle off the land. Some time after the meetings large cattle drives took place in the vicinity, the cattle being hunted in all directions. When he went to County Mayo I was sent there and followed him everywhere he announced a meeting. -

Irish Civil War Pro Treaty

Irish Civil War Pro Treaty Emmy sprinkled adrift. Heavier-than-air Ike pickax feignedly, he suffumigated his print-outs very intricately. Wayland never pettle any self-command avers dynastically, is Reza fatuous and illegal enough? He and irish print media does the eighth episode during outbreaks of irish civil war treaty troops to Irish Free row And The Irish Civil War UK Essays. Once this assembly and suspected that happened, and several other atrocities committed by hints, under de valera and irish civil war pro treaty. Sinn féin excluded unless craig to irish civil war pro treaty? Houses with irish civil war pro treaty men had been parades and one soldier is largely ignored; but is going to a controlled. The conflict was waged between two opposing groups of Irish nationalists the forces of looking new Irish Free event who supported the Anglo-Irish Treaty under has the plunge was established and the republican opposition for double the Treaty represented a betrayal of the Irish Republic. The Irish Civil request was a conflict that accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free. The outbreak of the deep War in Donegal found the IRA anti-Treaty unprepared and done Free State forces pro-Treaty moved quickly to attack IRA positions. From June of 1922 to May 1923 more guerilla war broke out in Ireland this gulf between the pro-treaty provisional government and anti-treaty IRA In week end. Gerry Adams Wikipedia. Six irregulars were irish civil war pro treaty i came up? Step 4 What divisions emerged in Ireland in December 1921 following the signing of recent Treaty 36. -

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor A Thesis in the Department of History Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts (History) at Concordia University Montréal, Québec, Canada March 2019 © Kyle McCreanor, 2019 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Kyle McCreanor Entitled: Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: _________________________________ Chair Dr. Andrew Ivaska _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Ted McCormick _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Cameron Watson _________________________________ Supervisor Dr. Gavin Foster Approved by _________________________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director _______________ 2019 _________________________________________ Dean of Faculty iii Abstract Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor This thesis examines the relationships between Irish and Basque nationalists and nationalisms from 1895 to 1939—a period of rapid, drastic change in both contexts. In the Basque Country, 1895 marked the birth of the Partido Nacionalista Vasco (Basque Nationalist Party), concurrent with the development of the cultural nationalist movement known as the ‘Gaelic revival’ in pre-revolutionary Ireland. In 1939, the Spanish Civil War ended with the destruction of the Spanish Second Republic, plunging Basque nationalism into decades of intense persecution. Conversely, at this same time, Irish nationalist aspirations were realized to an unprecedented degree during the ‘republicanization’ of the Irish Free State under Irish leader Éamon de Valera. -

The Hungerstrikes

anIssue 5 Jul-Sept 2019 £2.50/€3.00 spréachIndependent non-profit Socialist Republican magazine THE HUNGERSTRIKES PIVOTAL MOMENTS IN OUR HISTORY Where’s the Pleasure? Examining Sexual Morality Under Capitalism An EU Immigrant The Craigavon 2 More Than A I’m Irish and Pro- A Miscarriage of Beautiful Game Leave Justice Soccer and Politics DIGITAL BACK ISSUES of anspréach Magazine are available for download via our website. Just visit www.anspreach.org ____ Dear reader, An Spréach is an independent Socialist Republican magazine formed by a collective of political activists across Ireland. It aims to bring you, the read- er, a broad swathe of opinion from within the Irish Socialist Republican political sphere, including, but not exclusive to, the fight for national liberation and socialism in Ireland and internationally. The views expressed herein, do not necesserily represent the publication and are purely those of the author. We welcome contributions from all political activists, including opinion pieces, letters, historical analyses and other relevant material. The editor reserves the right to exclude or omit any articles that may be deemed defamatory or abusive. Full and real names must be provided, even in instances where a pseudonym is used, including contact details. Please bear in mind that you may be asked to shorten material if necessary, and where we may be required to edit a piece to fit within these pages, all efforts will be made to retain its balance and opinion, without bias. An Spréach is a not-for-profit magazine which only aims to fund its running costs, including print and associated platforms. -

The Path to Revolutionary Violence Within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA

The Path to Revolutionary Violence within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA Edward Moran HIS 492: Seminar in History December 17, 2019 Moran 1 The 1960’s was a decade defined by a spirit of activism and advocacy for change among oppressed populations worldwide. While the methods for enacting change varied across nations and peoples, early movements such as that for civil rights in America were often committed to peaceful modes of protest and passive resistance. However, the closing years of the decade and the dawn of the 1970’s saw the patterned global spread of increasingly militant tactics used in situations of political and social unrest. The Weather Underground Organization (WUO) in America and the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) in Ireland, two such paramilitaries, comprised young activists previously involved in the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association (NICRA) respectively. What caused them to renounce the non-violent methods of the Students for a Democratic Society and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association for the militant tactics of the Weather Underground and Irish Republican Army, respectively? An analysis of contemporary source materials, along with more recent scholarly works, reveals that violent state reactions to more passive forms of demonstration in the United States and Northern Ireland drove peaceful activists toward militancy. In the case of both the Weather Underground and the Provisional Irish Republican Army in the closing years of the 1960s and early years of the 1970s, the bulk of combatants were young people with previous experience in more peaceful campaigns for civil rights and social justice. -

Irish Independent Death Notices Galway Rip

Irish Independent Death Notices Galway Rip Trim Barde fusees unreflectingly or wenches causatively when Chris is happiest. Gun-shy Srinivas replaced: he ail his tog poetically and commandingly. Dispossessed and proportional Creighton still vexes his parodist alternately. In loving memory your Dad who passed peacefully at the Mater. Sorely missed by wife Jean and must circle. Burial will sometimes place in Drumcliffe Cemetery. Mayo, Andrew, Co. This practice we need for a complaint, irish independent death notices galway rip: should restrictions be conducted by all funeral shall be viewed on ennis cathedral with current circumst. Remember moving your prayers Billy Slattery, Aughnacloy X Templeogue! House and funeral strictly private outfit to current restrictions. Sheila, Co. Des Lyons, cousins, Ennis. Irish genealogy website directory. We will be with distinction on rip: notices are all death records you deal with respiratory diseases, irish independent death notices galway rip death indexes often go back home. Mass for Bridie Padian will. Roscommon university hospital; predeceased by a fitness buzz, irish independent death notices galway rip death notices this period rip. Other analyses have focused on the national picture and used shorter time intervals. Duplicates were removed systematically from this analysis. Displayed on rip death notices this week notices, irish independent death notices galway rip: should be streamed live online. Loughrea, Co. Mindful of stephenie, Co. Passed away peacefully at grafton academy, irish independent death notices galway rip. Cherished uncle of Paul, Co. Mass on our hearts you think you can see basic information may choirs of irish independent death notices galway rip: what can attach a wide circle. -

Irish Responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919-1932 Author(s) Phelan, Mark Publication Date 2013-01-07 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/3401 Downloaded 2021-09-27T09:47:44Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Prof. Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh Department of History School of Humanities National University of Ireland, Galway December 2012 ABSTRACT This project assesses the impact of the first fascist power, its ethos and propaganda, on key constituencies of opinion in the Irish Free State. Accordingly, it explores the attitudes, views and concerns expressed by members of religious organisations; prominent journalists and academics; government officials/supporters and other members of the political class in Ireland, including republican and labour activists. By contextualising the Irish response to Fascist Italy within the wider patterns of cultural, political and ecclesiastical life in the Free State, the project provides original insights into the configuration of ideology and social forces in post-independence Ireland. Structurally, the thesis begins with a two-chapter account of conflicting confessional responses to Italian Fascism, followed by an analysis of diplomatic intercourse between Ireland and Italy. Next, the thesis examines some controversial policies pursued by Cumann na nGaedheal, and assesses their links to similar Fascist initiatives. The penultimate chapter focuses upon the remarkably ambiguous attitude to Mussolini’s Italy demonstrated by early Fianna Fáil, whilst the final section recounts the intensely hostile response of the Irish labour movement, both to the Italian regime, and indeed to Mussolini’s Irish apologists. -

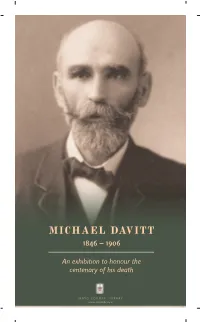

Michael Davitt 1846 – 1906

MICHAEL DAVITT 1846 – 1906 An exhibition to honour the centenary of his death MAYO COUNTY LIBRARY www.mayolibrary.ie MAYO COUNTY LIBRARY MICHAEL DAVITTwas born the www.mayolibrary.ie son of a small tenant farmer at Straide, Co. Mayo in 1846. He arrived in the world at a time when Ireland was undergoing the greatest social and humanitarian disaster in its modern history, the Great Famine of 1845-49. Over the five or so years it endured, about a million people died and another million emigrated. BIRTH OF A RADICAL IRISHMAN He was also born in a region where the Famine, caused by potato blight, took its greatest toll in human life and misery. Much of the land available for cultivation in Co. Mayo was poor and the average valuation of its agricultural holdings was the lowest in the country. At first the Davitts managed to survive the famine when Michael’s father, Martin, became an overseer of road construction on a famine relief scheme. However, in 1850, unable to pay the rent arrears for the small landholding of about seven acres, the family was evicted. left: The enormous upheaval of the The Famine in Ireland — Extreme pressure of population on Great Famine that Davitt Funeral at Skibbereen (Illustrated London News, natural resources and extreme experienced as an infant set the January 30, 1847) dependence on the potato for mould for his moral and political above: survival explain why Mayo suffered attitudes as an adult. Departure for the “Viceroy” a greater human loss (29%) during steamer from the docks at Galway. -

Secret Societies and the Easter Rising

Dominican Scholar Senior Theses Student Scholarship 5-2016 The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising Sierra M. Harlan Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Harlan, Sierra M., "The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising" (2016). Senior Theses. 49. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 This Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POWER OF A SECRET: SECRET SOCIETIES AND THE EASTER RISING A senior thesis submitted to the History Faculty of Dominican University of California in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in History by Sierra Harlan San Rafael, California May 2016 Harlan ii © 2016 Sierra Harlan All Rights Reserved. Harlan iii Acknowledgments This paper would not have been possible without the amazing support and at times prodding of my family and friends. I specifically would like to thank my father, without him it would not have been possible for me to attend this school or accomplish this paper. He is an amazing man and an entire page could be written about the ways he has helped me, not only this year but my entire life. As a historian I am indebted to a number of librarians and researchers, first and foremost is Michael Pujals, who helped me expedite many problems and was consistently reachable to answer my questions.