By Architect: Mohammad Abdel Qader Alfar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zakaria 2003 Institutional Issues for Advanced Transit S…

Institutional Issues for Deployment of Advanced Public Transportation Systems for Transit-Oriented Development in the Kuala Lumpur Metropolitan Area AY 2002/2003 Spring Report Zulina Zakaria Massachusetts Institute of Technology July 17, 2003 Institutional Issues for Deployment of Advanced Public Transportation Systems for TOD in KLMA Zulina Zakaria AY 2002/2003 Spring Report July 17, 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction .........................................................................................................................................................4 1.1 Existing Public Transportation and Traffic Congestion ...................................................................................4 1.2 Vision of Public Transportation and ITS ........................................................................................................5 1.3 Purpose of Report.......................................................................................................................................6 1.4 Report Organization ....................................................................................................................................7 2 Background .........................................................................................................................................................7 2.1 Problem of Urban Mobility in Developing Countries and Possible Solutions ....................................................7 2.2 Land Use–Transport Interactions and Transit Oriented Development .............................................................8 -

![[Title Over Two Lines (Shift+Enter to Break Line)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4038/title-over-two-lines-shift-enter-to-break-line-134038.webp)

[Title Over Two Lines (Shift+Enter to Break Line)]

BUS TRANSFORMATION PROJECT White Paper #2: Strategic Considerations October 2018 DRAFT: For discussion purposes 1 1 I• Purpose of White Paper II• Vision & goals for bus as voiced by stakeholders III• Key definitions IV• Strategic considerations Table of V• Deep-dive chapters to support each strategic consideration Contents 1. What is the role of Buses in the region? 2. Level of regional commitment to speeding up Buses? 3. Regional governance / delivery model for bus? 4. What business should Metrobus be in? 5. What services should Metrobus operate? 6. How should Metrobus operate? VI• Appendix: Elasticity of demand for bus 2 DRAFT: For discussion purposes I. Purpose of White Paper 3 DRAFT: For discussion purposes Purpose of White Paper 1. Present a set of strategic 2. Provide supporting analyses 3. Enable the Executive considerations for regional relevant to each consideration Steering Committee (ESC) to bus transformation in a neutral manner set a strategic direction for bus in the region 4 DRAFT: For discussion purposes This paper is a thought piece; it is intended to serve as a starting point for discussion and a means to frame the ensuing debate 1. Present a The strategic considerations in this paper are not an set of strategic exhaustive list of all decisions to be made during this considerations process; they are a set of high-level choices for the Bus Transformation Project to consider at this phase of for regional strategy development bus transformation Decisions on each of these considerations will require trade-offs to be continually assessed throughout this effort 5 DRAFT: For discussion purposes Each strategic consideration in the paper is 2. -

Towards a Green Economy in Jordan

Towards a Green Eco nomy in Jordan A SCOPING STUDY August 2011 Study commissioned by The United Nations Environment Programme In partnership with The Ministry of Environment of Jordan Authored by Envision Consulting Group (EnConsult) Jordan Towards a Green Economy in Jordan ii Contents 1. Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... vii 2. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 2.1 Objective of the Study ................................................................................................... 1 2.2 Green Economy Definition ........................................................................................... 1 2.3 Jordanian Government Commitment to Green Economy .................................... 1 3. Overarching Challenges for the Jordanian Economy............................................ 2 3.1 Unemployment ................................................................................................................. 2 3.2 Energy Security ............................................................................................................... 3 3.3 Resource Endowment and Use ................................................................................... 5 4. Key Sectors Identified for Greening the Economy ................................................. 7 4.1 Energy .................................................................................................................. -

Minit Mesyuarat Penuh Bil.06 2016

Mesyuarat Majlis Perbandaran Subang Jaya Bil. 06 Tahun 2016 Ruj. Fail : MPSJ/KHP/100 – 6/1/1Jld 3(5) MINIT MESYUARAT MAJLIS PERBANDARAN SUBANG JAYA BIL. 06 TAHUN 2016 Tarikh : 30 Jun 2016 (Khamis) Masa : 10.00 pagi hingga 11.00 pagi Tempat : Bilik Mesyuarat Kenanga, Aras 2, Ibu pejabat, Majlis Perbandaran Subang Jaya Kehadiran : Seperti di Lampiran A 1.0 BACAAN DOA Mesyuarat dimulakan dengan bacaan doa oleh Tuan Haji Mohd Zulkurnain Bin Che Ali, Pengarah Khidmat Pengurusan, Majlis Perbandaran Subang Jaya. 2.0 PERUTUSAN PENGERUSI YBhg. Dato’ Pengerusi memulakan mesyuarat dengan mengucapkan salam kepada semua yang hadir dan memaklumkan bahawa mesyuarat kali ini adalah Mesyuarat Penuh MPSJ Bil. 06/2016 dan seterusnya memaklumkan mengenai beberapa perkara berikut: 2.1 PROGRAM KETUK-KETUK SINGGAH SAHUR MAJLIS PERBANDARAN SUBANG JAYA 2016 Sukacita dimaklumkan bahawa Majlis Perbandaran Subang Jaya telah berjaya menganjurkan satu program yang dinamakan Program Ketuk-Ketuk Singgah Sahur MPSJ 2016 pada 10 Jun 2016 (Jumaat) bertempat di Pangsapuri Enggang, Bandar Kinrara. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 30 Jun 2016 1 Mesyuarat Majlis Perbandaran Subang Jaya Bil. 06 Tahun 2016 Pengisian program ini melibatkan aktiviti mengedarkan sumbangan barangan keperluan asas seperti beras, minyak masak dan gula kepada penghuni Pangsapuri Enggang. Program yang melibatkan sejumlah 30 unit rumah yang telah dikunjungi merupakan kerjasama MPSJ bersama AEON Big (M) Sdn. Bhd. dan Pavilion Reit Management. Adalah diharapkan semoga program sebegini dapat meringankan beban mereka yang kurang berkemampuan disamping menggalakkan Kerjasama Program-Program Tanggungjawab Sosial Korporat (Corporate Social Responsibility – CSR) diantara MPSJ dan pelbagai agensi. Pihak Majlis merakamkan ucapan terima kasih dan penghargaan kepada semua Ahli Majlis, Pegawai dan Warga Kerja MPSJ yang telah turut sama menjayakan program ini. -

National Strategy and Action Plan for Sustainable Consumption and Production in Jordan | 2016 - 2025

SCP National Strategy and Action Plan NATIONAL STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN FOR SUSTAINABLE CONSUMPTION AND PRODUCTION IN JORDAN | 2016 - 2025 SwitchMed Programme is funded by the European Union SwitchMed Programme is funded by the European Union SwitchMed Programme is implemented by the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), through the Mediterranean Action Plan (MAP) and its Regional Activity Centre for Sustainable Consumption and Production (SCP/RAC) and the Division of Technology, Industry and Economics (DTIE). For details on the SwitchMed Programme please contact [email protected] © Ministry of Environment. 2016 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the Ministry of Environment. Cover photo: www.shutterstock.com General disclaimers The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Ministry of Environment, the United Nations Environment Programme and of the European Union. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP and the European Union concerning the legal status of any country, territory or city or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

A Study of the Physical Formation of Medieval Cairo Rotch JUN 0 2 1989

IBN KHALDUN AND THE CITY: A Study of The Physical Formation of Medieval Cairo by Tawfiq F. Abu-Hantash B.Arch. University of Jordan Amman, Jordan June 1983 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURAL STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 1989 @ Tawfiq Abu-Hantash 1989. All rights reserved The author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author Tawfiq Abu-Hantash Department of Architecture 12 May 1989 Certified by Stanford Anderson Professor of History and Architecture Thesis Advisor Accepted by Juki Beinart, Chairman Departmen 1 Committee on Graduate Students Rotch MAS$,A1JUNS2OF TECjajjay 1NSTTE JUN 0 2 1989 WROM Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MITLibraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://Iibraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. The images contained in this document are of the best quality available. Abstract 2 IBN KHALDUN AND THE CITY: A Study of The Physical Formation of Medieval Cairo by Tawfiq Abu-Hantash Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 12, 1989 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies. -

016 Market Study with Focus on Potential for Eu High-Tech Solution Providers

Co-funded by MALAYSIA’S TRANSPORT & INFRASTRUCTURE SECTOR 2016 MARKET STUDY WITH FOCUS ON POTENTIAL FOR EU HIGH-TECH SOLUTION PROVIDERS Market Report 2016 Implemented By SEBSEAM-MSupport for European Business in South East Asia Markets Malaysia Component Publisher: EU-Malaysia Chamber of Commerce and Industry (EUMCCI) Suite 10.01, Level 10, Menara Atlan, 161B Jalan Ampang, 50450 Kuala Lumpu Malaysia Telephone : +603-2162 6298 r. Fax : +603-2162 6198 E-mail : [email protected] www.eumcci.com Author: Malaysian-German Chamber of Commerce and Industry (MGCC) www.malaysia.ahk.de Status: May 2016 Disclaimer: ‘This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the EU-Malaysia Chamber of Commerce and Industry (EUMCCI) and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union’. Copyright©2016 EU-Malaysia Chamber of Commerce and Industry. All Rights Reserved. EUMCCI is a Non-Profit Organization registered in Malaysia with number 263470-U. Privacy Policy can be found here: http://www.eumcci.com/privacy-policy. Malaysia’s Transport & Infrastructure Sector 2016 Executive Summary This study provides insights into the transport and infrastructure sector in Malaysia and identifies potentials and challenges of European high-technology service providers in the market and outlines the current situation and latest development in the transport and infrastructure sector. Furthermore, it includes government strategies and initiatives, detailed descriptions of the role of public and private sectors, the legal framework, as well as present, ongoing and future projects. The applied secondary research to collect data and information has been extended with extensive primary research through interviews with several government agencies and industry players to provide further insights into the sector. -

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & the Exuberance of Mamluk Design

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & The Exuberance of Mamluk Design Tarek A. El-Akkad Dipòsit Legal: B. 17657-2013 ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tesisenxarxa.net) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del s eu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tesisenred.net) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos. -

Malaysian News: Auto Fuel, Car Sales, Public Transit, Ports September 23, 2004

Malaysian News: Auto fuel, car sales, public transit, ports September 23, 2004 1. Calls have been made to move the nation's auto fleets towards becoming diesel driven, similar to Europe, in move to reduce emissions and costs 2. Car sales continue to increase, with non-national brand sale increases outpacing national brand sale increases 3. About 65% of KL's public transit capacity for rail and buses will be nationalized under a new agency. The purpose is to provide more integration and coordination of physical infrastructure, fare structure, routes and scheduling. This is a big change from the many separate privately owned rail and bus lines! 4. Port Klang's throughput continues to grow 5. Port Klang is moving to a new system of tracking cargo that requires shipping agents to provide additional information on freight. Shipping agents are refusing to provide new information and resulting impass could cause massive delays in Port Klang when new system is implemented Oct. 1. 6. Malaysia port has new system to route and inspect cargo in more automatic manner, but also has backup plan in place in case new system fails ******************************************************** ***1. Calls for move towards diesel as private auto fuel*** ******************************************************** http://www.bernama.com/ September 22, 2004 18:39 PM Call For Use Of More Diesel-Powered Engines KUALA LUMPUR, Sept 22 (Bernama) -- Tan Lian Hoe (BN-Bukit Gantang) Wednesday called for more use of diesel-powered engines as the fuel is cheaper than petrol. Tan said diesel was cheaper and cleaner, and engines which used the fuel emitted less noxious gas as compared to the more expensive petrol which produced a lot of carbon monoxide. -

Jordanian.Pdf

JORDANIAN Cultural Orientation TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: PROFILE ................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 Geography ................................................................................................................................ 1 Area .................................................................................................................................. 1 Geographic Divisions and Topographic Features ............................................................ 2 Climate ............................................................................................................................. 3 Bodies of Water ................................................................................................................ 4 Major Cities ............................................................................................................................. 5 Amman ............................................................................................................................. 5 Zarqa ................................................................................................................................. 5 Irbid .................................................................................................................................. 5 Aqaba ............................................................................................................................... -

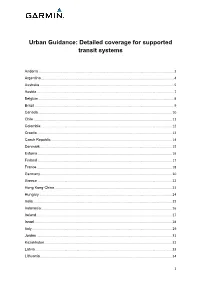

Urban Guidance: Detailed Coverage for Supported Transit Systems

Urban Guidance: Detailed coverage for supported transit systems Andorra .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Argentina ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Australia ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Austria .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Brazil ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ................................................................................................................................................ 10 Chile ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Colombia .............................................................................................................................................. 12 Croatia ................................................................................................................................................. -

The Sources of Ibn Tulun's Soffit Decoration

The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences The Sources of Ibn Tulun’s Soffit Decoration A Thesis Submitted to Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations Islamic Art and Architecture in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Master of Arts by Pamela Mahmoud Azab Under the Supervision of Dr. Bernard O’Kane December 2015 Acknowledgments I would like to dedicate this thesis to my late mother who encouraged me to pursue my masters. Unfortunately she passed away after my first year in the program, may her soul rest in peace. For all the good souls we lost these past years, my Mum, my Mother-in-law and my sister-in-law. I would like to thank my family, my dad, my brother, my husband, my sons Omar, Karim and my little baby girl Lina. I would like to thank my advisor Dr. O’Kane for his patience and guidance throughout writing the thesis and his helpful ideas. I enjoyed Dr. O’Kane’s courses especially “The Art of the book in the Islamic world”. I enjoyed Dr. Scanlon’s courses and his sense of humor, may his soul rest in peace. I also enjoyed Dr. Chahinda’s course “Islamic Architecture in Egypt and Syria” and her field trips. I feel lucky to have attended almost all courses in the Islamic Art and Architecture field during my undergraduate and graduate years at AUC. It is an honor to have a BA and an MA in Islamic Art and Architecture. I want to thank my friends, Nahla Mesbah for her support, encouragement, and help especially with Microsoft word, couldn’t have finished without her, and Rasha Aboul- Enein for driving me to the mosque and loaning me her camera.