CIVIL DEFENSE Chapter Lli.– CIVIL DEFENSE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fish Terminologies

FISH TERMINOLOGIES Monument Type Thesaurus Report Format: Hierarchical listing - class Notes: Classification of monument type records by function. -

The Effects of Nuclear War

The Effects of Nuclear War May 1979 NTIS order #PB-296946 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 79-600080 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D C, 20402 — Foreword This assessment was made in response to a request from the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations to examine the effects of nuclear war on the populations and economies of the United States and the Soviet Union. It is intended, in the terms of the Committee’s request, to “put what have been abstract measures of strategic power into more comprehensible terms. ” The study examines the full range of effects that nuclear war would have on civilians: direct effects from blast and radiation; and indirect effects from economic, social, and politicai disruption. Particular attention is devoted to the ways in which the impact of a nuclear war would extend over time. Two of the study’s principal findings are that conditions would con- tinue to get worse for some time after a nuclear war ended, and that the ef- fects of nuclear war that cannot be calculated in advance are at least as im- portant as those which analysts attempt to quantify. This report provides essential background for a range of issues relating to strategic weapons and foreign policy. It translates what is generally known about the effects of nuclear weapons into the best available estimates about the impact on society if such weapons were used. It calls attention to the very wide range of impacts that nuclear weapons would have on a complex industrial society, and to the extent of uncertainty regarding these impacts. -

Bob Farquhar

1 2 Created by Bob Farquhar For and dedicated to my grandchildren, their children, and all humanity. This is Copyright material 3 Table of Contents Preface 4 Conclusions 6 Gadget 8 Making Bombs Tick 15 ‘Little Boy’ 25 ‘Fat Man’ 40 Effectiveness 49 Death By Radiation 52 Crossroads 55 Atomic Bomb Targets 66 Acheson–Lilienthal Report & Baruch Plan 68 The Tests 71 Guinea Pigs 92 Atomic Animals 96 Downwinders 100 The H-Bomb 109 Nukes in Space 119 Going Underground 124 Leaks and Vents 132 Turning Swords Into Plowshares 135 Nuclear Detonations by Other Countries 147 Cessation of Testing 159 Building Bombs 161 Delivering Bombs 178 Strategic Bombers 181 Nuclear Capable Tactical Aircraft 188 Missiles and MIRV’s 193 Naval Delivery 211 Stand-Off & Cruise Missiles 219 U.S. Nuclear Arsenal 229 Enduring Stockpile 246 Nuclear Treaties 251 Duck and Cover 255 Let’s Nuke Des Moines! 265 Conclusion 270 Lest We Forget 274 The Beginning or The End? 280 Update: 7/1/12 Copyright © 2012 rbf 4 Preface 5 Hey there, I’m Ralph. That’s my dog Spot over there. Welcome to the not-so-wonderful world of nuclear weaponry. This book is a journey from 1945 when the first atomic bomb was detonated in the New Mexico desert to where we are today. It’s an interesting and sometimes bizarre journey. It can also be horribly frightening. Today, there are enough nuclear weapons to destroy the civilized world several times over. Over 23,000. “Enough to make the rubble bounce,” Winston Churchill said. The United States alone has over 10,000 warheads in what’s called the ‘enduring stockpile.’ In my time, we took care of things Mano-a-Mano. -

Introduction

Chapter 1 Introduction Life is given to us, we earn it by giving it. Rabindranath Tagore 1.1 UNDERGROUND SPACE AND ITS REQUIREMENT The joy of traveling through underground metros, rail, and road tunnels, espe- cially the half-tunnels in mountains and visiting caves, cannot be described. Modern underground infrastructures are really engineering marvels of the 21st century. The space created below the ground surface is generally known as underground space. Underground space may either be developed by open excavation in soft strata or soil, the top of which is subsequently covered to get the space below, or created by excavation in hard strata or rock. Underground space is available almost everywhere, which may provide the site for activities or infrastructure that are difficult or impossible to install above- ground or whose presence aboveground is unacceptable or undesirable. Another fundamental characteristic of underground space lies in the natural protection it offers to whatever is placed underground. This protection is simultaneously mechanical, thermal, acoustic, and hydraulic (i.e., watertight). It is effective not only in relation to the surface, but also within the underground space itself. Thus underground infrastructure offers great safety against all natural disasters and nuclear wars, ultraviolet rays from holes in the ozone layer, global warm- ing, electromagnetic pollution, and massive solar storms. Increasing population and the developing needs and aspirations of human- kind for our living environment require increasing provision of space of all kinds. This has become a high priority for most “mega cities” since the closing years of the 20th century. The world’s population is becoming more urbanized, at an unprecedented pace. -

Appendix 1: Three Level Hierarchy Monument Classification System

New Forest Remembers: Untold Stories of World War II April 2013 Appendix 1: Three Level Hierarchy Monument Classification System Top Term Broad Term Monument Type ADMIRALTY SIGNAL ESTABLISHMENT ADMIRALTY SIGNAL STATION AIRCRAFT CRASH SITE AIRSHIP STATION AUXILIARY FIRE STATION AUXILIARY HOSPITAL BOMB CRATER BOMBING RANGE MARKER AIR DEFENCE SITE AIR DEFENCE SITE ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY AIR DEFENCE SITE ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY COMMAND POST AIR DEFENCE SITE ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY ANTI AIRCRAFT GUN EMPLACEMENT AIR DEFENCE SITE ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY BATTERY OBSERVATION POST AIR DEFENCE SITE ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY HEAVY ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY AIR DEFENCE SITE ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY LIGHT ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY AIR DEFENCE SITE ANTI AIRCRAFT BATTERY Z BATTERY AIR DEFENCE SITE ANTI AIRCRAFT GUN TOWER AIR DEFENCE SITE ANTI AIRCRAFT OPERATIONS ROOM AIR DEFENCE SITE BARRAGE BALLOON SITE AIR DEFENCE SITE BARRAGE BALLOON SITE BARRAGE BALLOON CENTRE AIR DEFENCE SITE BARRAGE BALLOON SITE BARRAGE BALLOON GAS DEPOT Maritime Archaeology Ltd MA Ltd 1832 Room W1/95, National Oceanography Centre, Empress Dock, Southampton. SO14 3ZH. www.maritimearchaeology.co.uk Page 1 of 79 New Forest Remembers: Untold Stories of World War II April 2013 Top Term Broad Term Monument Type AIR DEFENCE SITE BARRAGE BALLOON SITE BARRAGE BALLOON HANGAR AIR DEFENCE SITE BARRAGE BALLOON SITE BARRAGE BALLOON MOORING AIR DEFENCE SITE BARRAGE BALLOON SITE BARRAGE BALLOON SHELTER AIR DEFENCE SITE SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY AIR DEFENCE SITE SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY BATTERY OBSERVATION -

A Practical Handbook for Emergency Planning

In Advance Safe A Practical Handbook for Accessible Emergency Planning Free Effective training and materials on EVacuation and ACommodation of People with Disabilities Project Safe EV-AC Table of Contents Chapter 1: History of Evacuation of People with Disabilities Chapter 2: Overcoming Fear and Anxiety Chapter 3: EV-AC Accommodation Process Chapter 4: Accommodation Options Chapter 5: Specific Disaster Fact Sheets Chapter 6: Evacuation by Setting Chapter 7: Resources Chapter 1: History of Evacuation of People with Disabilities Project Safe EV-AC In Advance – Chapter 1 CHAPTER 1: HISTORY OF EVACUATION OF PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES The United States has nearly 50 million people with disabilities, which is over 19% of the entire population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000a). Many of these individuals do not have information about how to safely evacuate their homes or workplaces (Taylor, 2001). In addition, many evacuation materials do not address the 4,000,000 people in institutions (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000b), the nearly 400,000 State and Federal prison inmates with disabilities (Maruschak & Beck, 1997), or the over 400,000 postsecondary students with disabilities (National Center for Education Statistics, 2002). Interest in emergency evacuation planning has increased dramatically since the September 11 terrorist attacks (Batiste & Loy, 2005). History has taught us that planning is the key to successful evacuation so it is imperative that evacuation planning includes individuals from these overlooked populations. In an emergency, people often need to quickly evacuate buildings, vehicles, or outdoor areas, and planning for emergency evacuation dramatically increases the chance for successful evacuation. However, many individuals, business owners, and facilities managers do not have emergency evacuation plans. -

Securing the Blast Site to Prevent Blasting Related Injuries Blasting Safety - Revisiting Site Security by T

Securing the Blast Site to Prevent Blasting Related Injuries Blasting Safety - Revisiting Site Security By T. S. Bajpayee, Harry C.Verakis, and Thomas E. Lobb This article examines the factors related to injuries due to inadequate blasting shelters and blast area security, and identifies miti gation techniques. The key concepts are: (a) accurate determination of the bounds of the blast area, (b) clearing employees from the blast area, (c) effective access control, (d) use of adequate blasting shel ters, (e) efficient communications, and (f) training. Fundamentals are reviewed with an emphasis on analyzing task elements and identifying root causes for selected blasting accidents. Mitigating techniques are presented along with discussions and examples. Introduction During 1978-2003, blast area security accounted for Domestic consumption of explosives during 2003 was 41% of all blasting related injuries reported by surface approximately 5.05 billion pounds and about 89% (4.5 mines. The corresponding figure for underground mines billion pounds) was used by the mining industry [USGS, was 56%. The data indicates that injuries from inade 2004]. Blasting is a great tool in fragmenting and loos quate blast area security are more prevalent in under ening rock and other materials for easier handling and ground blasting. removal by mining equipment. However, blasting cre Verakis & Lobb [2003 with updated data] analyzed ates serious concerns for the mine operators and miners more recent data (1994-2003) to assess any changes in in terms of blast area security. the role of blast area security. During this period, blast One thousand one hundred and thirty-one blasting- area security accounted for nearly 41.6% of all blasting- related injuries were reported by the mining industry related injuries in surface and underground mines. -

Aa Box ABATTOIR ABBEY Abbey Barn Abbey Barn Abbey Bridge Abbey Bridge Abbey Church Abbey Church Abbey Gate Abbey Gate Abbey Gate

Aa Box Abbey Bridge USE : MOTORING TELEPHONE BOX USE : ABBEY ABATTOIR Abbey Bridge UF : Slaughter House USE : BRIDGE UF : Butching House BT : FOOD PROCESSING SITE Abbey Church RT : BUTCHERY SITE USE : ABBEY RT : SHAMBLES RT : SMOKE HOUSE Abbey Church RT : GLUE FACTORY USE : CHURCH RT : TANNERY RT : HORSEHAIR FACTORY Abbey Gate SN : A building where animals are slaughtered. USE : ABBEY ABBEY Abbey Gate UF : Benedictine Abbey UF : Arrouiasian Abbey USE : GATE UF : Augustinian Abbey UF : Victorine Abbey Abbey Gatehouse UF : Tironian Abbey USE : GATEHOUSE UF : Savigniac Abbey UF : Premonstratensian Abbey Abbey Gatehouse UF : Franciscan Abbey USE : ABBEY UF : Cistercian Abbey UF : Cluniac Abbey Abbey Kitchen UF : Bridgettine Abbey USE : ABBEY UF : Convent Chapel UF : Abbey Barn Abbey Kitchen UF : Abbey Bridge USE : KITCHEN UF : Abbey Church UF : Abbey Gate Abbey Wall UF : Abbey Gatehouse USE : PRECINCT WALL UF : Abbey Kitchen UF : Independent Abbey UF : Tironensian Abbey Abbots House UF : Conventual Chapel USE : MONASTIC DWELLING UF : Conventual Church UF : Farmery Abbots Lodging BT : RELIGIOUS HOUSE USE : MONASTIC DWELLING RT : ALMONRY RT : GUEST HOUSE ABBOTS PALACE RT : KITCHEN BT : PALACE RT : CHAPTER HOUSE SN : The official residence of an abbot. RT : CATHEDRAL RT : PRECINCT WALL ABBOTS SUMMER PALACE RT : DOUBLE HOUSE BT : PALACE RT : FRIARY RT : BISHOPS SUMMER PALACE RT : MONASTERY SN : An official residence of an abbot during the summer RT : NUNNERY months. RT : PRECEPTORY RT : PRIORY ABLUTIONS BLOCK RT : GATEHOUSE BT : DOMESTIC MILITARY BUILDING RT : REFECTORY BT : WASHING PLACE RT : CONVENT SCHOOL SN : A building housing washing facilities and toilets. The RT : CURFEW BELL TOWER term occurs mainly in a military context. -

Raf Culmhead

RAF CULMHEAD Second Edition Airfield Research Publishing for: Somerset County Council Taunton Deane Borough Council Blackdown Hills AONB 2 Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 SurveyMethodology ............................... ............. 5 1.2 Acknowledgements................................ ............. 5 2 Glossaryof terms 6 3 Background 6 4 Construction and layout 7 4.1 Runways ......................................... ......... 7 4.2 Buildings ....................................... ........... 7 4.3 AircraftHardstandingsandFighterPens . ..................... 10 4.4 AdditionalAirfieldDefences . ................. 12 5 Operational History 12 6 Gazetteer of surviving structures 18 6.1 TechnicalSite(Airfield) . ................ 18 6.2 Dispersedanti-aircraftmachine-gunsite . ....................... 47 6.3 Sewagedisposalsite .............................. .............. 47 6.4 Administrationsite .............................. ............... 53 6.5 RAFcommunalsite................................. ............ 54 6.6 RAFSiteNo.1 ..................................... .......... 56 6.7 RAFSiteNo.2 ..................................... .......... 57 6.8 RAFSiteNo.3 ..................................... .......... 57 6.9 WAAFCommunalandSiteNo.1 . ............ 58 6.10WAAFSiteNo.2................................... ........... 60 6.11 SickQuarters(LittleFulwoodHouse) . .................... 60 6.12 Dispersedsite(CanonsgroveHouse) . .................... 60 7 Conclusions 60 7.1 TechnicalSites .................................. ............. 63 7.2 DomesticSites -

Incorporating Civil-Defense Shelter Space in New Underground Construction*

INCORPORATING CIVIL-DEFENSE SHELTER SPACE IN NEW UNDERGROUND CONSTRUCTION* C. V. Chester Solar and Special Studies Section Energy Division Oak Ridge National Laboratory Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37830 By acceptance of this article, the publisher or recipient acknowledges the U.S. Government's right to retain a non-exclusive, royalty-free license in and to any copyright covering the article. *Research sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy under contract W-7405-eng-26 with the Union Carbide Corporation. Neither me United S'aies Go we v thereol, nor any ot their employee information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, ot DISTRIBUTION Of IHIS OOCUMENr IS UNLMTED rifi^H or ivijwly o^ncd c<3^ts. Pni&fcncG tiO'Cin to uny <ppci?ic by trade name, trade mark, mjnufacturer, o' otherwise, does or anv agency ihereol. The s and ocinioni oi authors expressed herein do n e'lect IMosa of ;he i 'nned Su Government •' any agency iheieo*. INCORPORATING CIVIL-DEFENSE SHELTER SPACE IN NEW UNDERGROUND CONSTRUCTION* by C. V. Chester Energy Division Oak Ridge National Laboratory Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37830 ABSTRACT At the present time, the population of the U.S. is approximately ten times more vulnerable to nuclear weapons than the Soviet population. This vulnerability can be reduced rapidly by urban evacuation in a crisis. However, the need to keep the essential economy running in a crisis, as well as coping with attacks on short warning, makes the construction of shelter space where people live very desirable. This can be done most economically by slightly modifying underground con- struction intended for peacetime use. -

New Committee

May 2011 You are invited by the Eliot Chapel Board of Trustees for two events of fellowship and understanding. Saturday, May 14 100 South Taylor Ave. Kirkwood, MO 6:30 – 8:30 pm 63122-4310 (314) 821-0911 A Potluck Dinner and Board Information Night www.eliotchapel.org and Office Hours Monday - Friday 8:00 to 4:00 Sunday 9:00 to 1:00 Sunday, May 15 following the 11:00 service Our Mission The Congregational Annual Meeting Eliot Chapel, a Unitarian Universalist You will learn: community, • How the Appreciative Inquiry goals are articu- gathers to foster lated in the revised Values and Mission of Eliot free religious thought, Chapel. nurture spiritual growth, • How policy governance reflects these goals and act for social justice. and helps the leadership of Eliot and enables the church to achieve these goals. We will take a look back at accomplishments Board of Trustees: of the past year and look forward to the Brent Vaughn, Chair bright future of Eliot Chapel. Mike Antoine, Chair-elect William Lemon, Secretary RSVP for childcare by May 11 to the church office at David Cox, Treasurer [email protected] or 314-821-0911. Dave Day Bill Erdman Potluck dishes: Marc Fried A-F: drinks G-L: salad and bread M-R: main dish S-Z: dessert Pat Gray Please sign up on the bulletin board. Steve Lawrence Mary Meihaus Page 1 Eliot Chapel Staff RE Gets Ready to Wrap Up Year News from the Religious Education Team Rev. Dr. David Keyes, Interim Minister Rev. Dr. Susan Videen, Minister of Pastoral Care What an exciting year we have had in Religious Rev. -

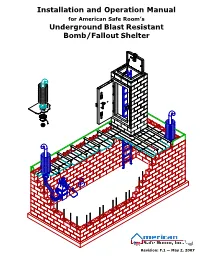

Installation and Operation Manual Underground Blast Resistant Bomb

Installation and Operation Manual for American Safe Room’s Underground Blast Resistant Bomb/Fallout Shelter Revision: F.1 — May 2, 2007 Underground Blast Resistant Fallout Shelter Revision: F.1 — May 2, 2007 Table of Contents Forward ................................................................................................................... 5 Contact information ...................................................................................................... 6 Description — general discussion ................................................................................... 7 Description — principals of a protected space .................................................................. 8 Description — components of a protected space .............................................................. 9 Description — components of a protected space, continued............................................. 10 Description — verifying that you have a true protected space .......................................... 10 Description — entry and exit ....................................................................................... 11 Description — options ................................................................................................ 12 Description — major components ................................................................................. 13 Choosing the location ................................................................................................. 14 Excavation ...............................................................................................................