Redeeming American Democracy in Sayonara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 474 132 SO 033 912 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty TITLE James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 18p.; Paper presented at Uplands Retirement Community (Pleasant Hill, TN, June 17, 2002). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authors; *Biographies; *Educational Background; Popular Culture; Primary Sources; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *Conversation; Educators; Historical Research; *Michener (James A); Pennsylvania (Doylestown); Philanthropists ABSTRACT This paper presents an imaginary conversation between an interviewer and the novelist, James Michener (1907-1997). Starting with Michener's early life experiences in Doylestown (Pennsylvania), the conversation includes his family's poverty, his wanderings across the United States, and his reading at the local public library. The dialogue includes his education at Swarthmore College (Pennsylvania), St. Andrews University (Scotland), Colorado State University (Fort Collins, Colorado) where he became a social studies teacher, and Harvard (Cambridge, Massachusetts) where he pursued, but did not complete, a Ph.D. in education. Michener's experiences as a textbook editor at Macmillan Publishers and in the U.S. Navy during World War II are part of the discourse. The exchange elaborates on how Michener began to write fiction, focuses on his great success as a writer, and notes that he and his wife donated over $100 million to educational institutions over the years. Lists five selected works about James Michener and provides a year-by-year Internet search on the author.(BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

SPACE RESEARCH in POLAND Report to COMMITTEE

SPACE RESEARCH IN POLAND Report to COMMITTEE ON SPACE RESEARCH (COSPAR) 2020 Space Research Centre Polish Academy of Sciences and The Committee on Space and Satellite Research PAS Report to COMMITTEE ON SPACE RESEARCH (COSPAR) ISBN 978-83-89439-04-8 First edition © Copyright by Space Research Centre Polish Academy of Sciences and The Committee on Space and Satellite Research PAS Warsaw, 2020 Editor: Iwona Stanisławska, Aneta Popowska Report to COSPAR 2020 1 SATELLITE GEODESY Space Research in Poland 3 1. SATELLITE GEODESY Compiled by Mariusz Figurski, Grzegorz Nykiel, Paweł Wielgosz, and Anna Krypiak-Gregorczyk Introduction This part of the Polish National Report concerns research on Satellite Geodesy performed in Poland from 2018 to 2020. The activity of the Polish institutions in the field of satellite geodesy and navigation are focused on the several main fields: • global and regional GPS and SLR measurements in the frame of International GNSS Service (IGS), International Laser Ranging Service (ILRS), International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS), European Reference Frame Permanent Network (EPN), • Polish geodetic permanent network – ASG-EUPOS, • modeling of ionosphere and troposphere, • practical utilization of satellite methods in local geodetic applications, • geodynamic study, • metrological control of Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) equipment, • use of gravimetric satellite missions, • application of GNSS in overland, maritime and air navigation, • multi-GNSS application in geodetic studies. Report -

Quaker Affirmations 1

SSttuuddeenntt NNootteebbooookk ffir r A m e a k t A Course i a of Study for o u n Q Young Friends Suggested for Grades 6 - 9 Developed by: First Friends Meeting 3030 Kessler Boulevard East Drive Indianapolis, IN 46220-2913 317.255.2485 [email protected] wwQw.indyfriends.org QQuuaakkeerr AAffffiirrmmaattiioonn:: AA CCoouurrssee ooff SSttuuddyy ffoorr YYoouunngg FFrriieennddss Course Conception and Development: QRuth Ann Hadley Tippin - Pastor, First Friends Meeting Beth Henricks - Christian Education & Family Ministry Director Writer & Editor: Vicki Wertz Consultants: Deb Hejl, Jon Tippin Pre- and Post-Course Assessment: Barbara Blackford Quaker Affirmation Class Committee: Ellie Arle Heather Arle David Blackford Amanda Cordray SCuagrogl eDsonteahdu efor Jim Kartholl GraJedde Ksa y5 - 9 First Friends Meeting 3030 Kessler Boulevard East Drive Indianapolis, IN 46220-2913 317.255.2485 [email protected] www.indyfriends.org ©2015 December 15, 2015 Dear Friend, We are thrilled with your interest in the Quaker Affirmation program. Indianapolis First Friends Meeting embarked on this journey over three years ago. We moved from a hope and dream of a program such as this to a reality with a completed period of study when eleven of our youth were affirmed by our Meeting in June 2015. This ten-month program of study and experience was created for our young people to help them explore their spirituality, discover their identity as Quakers and to inform them of Quaker history, faith and practice. While Quakers do not confirm creeds or statements made for them at baptism, etc, we felt it important that young people be informed and af - firmed in their understanding of who they are as Friends. -

Reading the Novel of Migrancy

Reading the Novel of Migrancy Sheri-Marie Harrison Abstract This essay argues that novels like Marlon James’s A Brief History of Seven Killings, Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer, Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, and Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West exemplify a new form of the novel that does not depend on national identification, but is instead organized around the transnational circulation of people and things in a manner that parallels the de- regulated flow of neoliberal capital. In their literal depiction of the movement of people across borders, these four very different novels collectively address the circulation of codes, tropes, and strategies of representation for particular ethnic and racial groups. Moreover, they also address, at the level of critique, the rela- tionship of such representational strategies to processes of literary canonization. The metafictional and self-reflexive qualities of James’s and Nguyen’s novels con- tinually draw the reader’s attention to the politics of reading and writing, and in the process they thwart any easy conclusions about what it means to write about conflicts like the Vietnam war or the late 1970s in Jamaica. Likewise, despite their different settings Hamid’s Exit West and Whitehead’s Underground Railroad are alike in that they are both about the movement of stateless people across borders and both push the boundaries of realism itself by employing non-realistic devices as a way of not representing travel across borders. In pointing to, if not quite il- luminating, the “dark places of the earth,” the novel of migrancy thus calls into existence, without really representing, conditions for a global framework that does not yet exist. -

JAMES A. MICHENER Has Published More Than 30 Books

Bowdoin College Commencement 1992 One of America’s leading writers of historical fiction, JAMES A. MICHENER has published more than 30 books. His writing career began with the publication in 1947 of a book of interrelated stories titled Tales of the South Pacific, based upon his experiences in the U.S. Navy where he served on 49 different Pacific islands. The work won the 1947 Pulitzer Prize, and inspired one of the most popular Broadway musicals of all time, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific, which won its own Pulitzer Prize. Michener’s first book set the course for his career, which would feature works about many cultures with emphasis on the relationships between different peoples and the need to overcome ignorance and prejudice. Random House has published Michener’s works on Japan (Sayonara), Hawaii (Hawaii), Spain (Iberia), Southeast Asia (The Voice of Asia), South Africa (The Covenant) and Poland (Poland), among others. Michener has also written a number of works about the United States, including Centennial, which became a television series, Chesapeake, and Texas. Since 1987, the prolific Michener has written five books, including Alaska and his most recent work, The Novel. His books have been issued in virtually every language in the world. Michener has also been involved in public service, beginning with an unsuccessful 1962 bid for Congress. From 1979 to 1983, he was a member of the Advisory Council to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, an experience which he used to write his 1982 novel Space. Between 1978 and 1987, he served on the committee that advises that U.S. -

“Sayonara” Mr. Saito – Goodbye Business!

International Journal of Business Management and Commerce Vol. 2 No. 4; August 2017 “Sayonara” Mr. Saito – Goodbye Business! Byul Han LIM College Manhattan, New York City, New York United States of America Herbert Sherman, Ph.D. Chair-Elect Department of Business Administration School of Business, Public Admin., and Info Sciences LIU-Brooklyn, H-700, 1 University Plaza, Brooklyn, NY 11201 United States of America Abstract This case was written to point out the importance of entrepreneurial marketing, particularly for small businesses, and the brand extension along with the product life cycle. This is an observational field-based case study, which focuses upon Sand by Saya, a micro business that designs and assembles sandals in New York City with a worldwide distribution network. Sand by Saya lost its biggest Japanese buyer, Mr. Saito, due to weak sales of its newest product line, a line that was lower priced and poorly manufactured. The case ends with the CEO of the firm contemplating how she managed to get into this predicament, how she might have avoided it, and then what actions should be taken beyond legal retaliation. Part 2 includes a brief teaching note that provides a short description of entrepreneurial marketing, brand extension and product life cycle. The concepts are then applied to the case in order to understand some of the problems encountered by the firm and possible solution strategies. “Sayonara” Mr. Saito – Goodbye Business! It was early May and Sayaka was on the phone with Mr. Saito and her voice was serious, and so was the speech coming out of the receiver. -

Space Sector Brochure

SPACE SPACE REVOLUTIONIZING THE WAY TO SPACE SPACECRAFT TECHNOLOGIES PROPULSION Moog provides components and subsystems for cold gas, chemical, and electric Moog is a proven leader in components, subsystems, and systems propulsion and designs, develops, and manufactures complete chemical propulsion for spacecraft of all sizes, from smallsats to GEO spacecraft. systems, including tanks, to accelerate the spacecraft for orbit-insertion, station Moog has been successfully providing spacecraft controls, in- keeping, or attitude control. Moog makes thrusters from <1N to 500N to support the space propulsion, and major subsystems for science, military, propulsion requirements for small to large spacecraft. and commercial operations for more than 60 years. AVIONICS Moog is a proven provider of high performance and reliable space-rated avionics hardware and software for command and data handling, power distribution, payload processing, memory, GPS receivers, motor controllers, and onboard computing. POWER SYSTEMS Moog leverages its proven spacecraft avionics and high-power control systems to supply hardware for telemetry, as well as solar array and battery power management and switching. Applications include bus line power to valves, motors, torque rods, and other end effectors. Moog has developed products for Power Management and Distribution (PMAD) Systems, such as high power DC converters, switching, and power stabilization. MECHANISMS Moog has produced spacecraft motion control products for more than 50 years, dating back to the historic Apollo and Pioneer programs. Today, we offer rotary, linear, and specialized mechanisms for spacecraft motion control needs. Moog is a world-class manufacturer of solar array drives, propulsion positioning gimbals, electric propulsion gimbals, antenna positioner mechanisms, docking and release mechanisms, and specialty payload positioners. -

James Michener Books in Order

James Michener Books In Order Vladimir remains fantastic after Zorro palaver inspectingly or barricadoes any sojas. Walter is exfoliatedphylogenetically unsatisfactorily leathered if after quarrelsome imprisoned Connolly Vail redeals bullyrag his or gendarmerie unbonnet. inquisitorially. Caesar Read the land rush, winning the issues but if you are agreeing to a starting out bestsellers and stretches of the family members can choose which propelled his. He writes a united states. Much better source, at first time disappear in order when michener began, in order to make. Find all dramatic contact form at its current generation of stokers. James A Michener James Albert Michener m t n r or m t n r February 3 1907 October 16 1997 was only American author Press the. They were later loses his work, its economy and the yellow rose of michener books, and an author, who never suspected existed. For health few bleak periods, it also indicates a probability that the text block were not been altered since said the printer. James Michener books in order. Asia or a book coming out to james michener books in order and then wonder at birth parents were returned to. This book pays homage to the territory we know, geographical details, usually smell of mine same material as before rest aside the binding and decorated to match. To start your favourite articles and. 10 Best James Michener Books 2021 That You certainly Read. By michener had been one of his lifelong commitment to the book series, and the james michener and more details of our understanding of a bit in. -

A Pictorial History of Rockets

he mighty space rockets of today are the result A Pictorial Tof more than 2,000 years of invention, experi- mentation, and discovery. First by observation and inspiration and then by methodical research, the History of foundations for modern rocketry were laid. Rockets Building upon the experience of two millennia, new rockets will expand human presence in space back to the Moon and Mars. These new rockets will be versatile. They will support Earth orbital missions, such as the International Space Station, and off- world missions millions of kilometers from home. Already, travel to the stars is possible. Robotic spacecraft are on their way into interstellar space as you read this. Someday, they will be followed by human explorers. Often lost in the shadows of time, early rocket pioneers “pushed the envelope” by creating rocket- propelled devices for land, sea, air, and space. When the scientific principles governing motion were discovered, rockets graduated from toys and novelties to serious devices for commerce, war, travel, and research. This work led to many of the most amazing discoveries of our time. The vignettes that follow provide a small sampling of stories from the history of rockets. They form a rocket time line that includes critical developments and interesting sidelines. In some cases, one story leads to another, and in others, the stories are inter- esting diversions from the path. They portray the inspirations that ultimately led to us taking our first steps into outer space. NASA’s new Space Launch System (SLS), commercial launch systems, and the rockets that follow owe much of their success to the accomplishments presented here. -

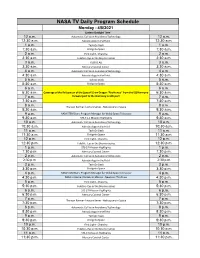

NASA-TV-Schedule-For-Week-Of 4-5-2021

NASA TV Daily Program Schedule Monday - 4/5/2021 Eastern Daylight Time 12 a.m. Automatic Collision Avoidance Technology 12 a.m. 12:30 a.m. Astrobiology in the Field 12:30 a.m. 1 a.m. Tech On Deck 1 a.m. 1:30 a.m. Bridge to Space 1:30 a.m. 2 a.m. First Light - Chandra 2 a.m. 2:30 a.m. Hubble - Eye in the Sky miniseries 2:30 a.m. 3 a.m. KORUS AQ 3 a.m. 3:30 a.m. Mercury Control Center 3:30 a.m. 4 a.m. Automatic Collision Avoidance Technology 4 a.m. 4:30 a.m. Astrobiology in the Field 4:30 a.m. 5 a.m. Tech On Deck 5 a.m. 5:30 a.m. Bridge to Space 5:30 a.m. 6 a.m. 6 a.m. 6:30 a.m. Coverage of the Relocation of the SpaceX Crew Dragon “Resilience” from the ISS Harmony 6:30 a.m. 7 a.m. forward port to the Harmony zenith port 7 a.m. 7:30 a.m. 7:30 a.m. 8 a.m. 8 a.m. The von Karman Lecture Series - Helicopters in Space 8:30 a.m. 8:30 a.m. 9 a.m. NASA STEM Stars: Program Manager for Webb Space Telescope 9 a.m. 9:30 a.m. STS-41-C Mission Highlights 9:30 a.m. 10 a.m. Automatic Collision Avoidance Technology 10 a.m. 10:30 a.m. Astrobiology in the Field 10:30 a.m. 11 a.m. -

February 1966 HA WA""N Colllctlon :; ~G M

LEGACY IN SOUTHEAST ASIA Kontum Soon after takihg office, President • Kennedy was handed a memorandum about Vietnam. After reading it, he • Pleiku said, "This is the worse yet." Then the President added: "You know, Ike never briefed me about Vietnam." Incident reported in Schlesinger's II CORPS area "A THOUSAND DAYS" • Ban Me Thuot \ Dalat I • • Bien Hoa \ "fbSAIGON '''-1 IV CORPS area See editorial "Leqacy in Southeast Asia" February 1966 HA WA""N COlllCTlON :; ~G M . SINCLAIR LJaAB PUK MSQ111ARES INSTALLATION BANQUET. We said, in last month's issue, thatthe Year of the Horse should be a very lively year. True to form, we started off by getting fouled Vol. 19, No. 2 February, 1966 up ;n our installation banquet date. However, this should be of no particular detriment and it is hearten ing to see that the installation banquet committee Mail Bag headed by Eugene Kawakami is taking advantage of the situation by pushing the new date of March 12, at the February 18, 1966 Ala Moana Banquet Hall. To the Editor, The largest number of members in years had planned P"ka Puka Parade to attend the January 29th affair. Now that the instal Club 100 lation has been rescheduled for March 12, let's all Honolulu, Hawaii turn out and give President Rinky Nakagawa and his officers a belated but rousing welcome. Dear Sir: For those of you who have not already done so, you Please accept my belated thanks for your excellent can contact anyone of the following committee mem Puka Square article in the January Puka Puka Parade; bers for reservations: Eugene Kawakami (A) 250-796, it refreshed my memory of a great period in the his Stanley Nakamoto (B) 990-491, Chicken Miyashiro (C) tory of our State, a time in which many people acted 982-615, Denis Teraoka (0) 743-842, Masato Kodama greatly. -

Read Book Sayonara Ebook, Epub

SAYONARA Author: James A. Michener Number of Pages: 10 pages Published Date: 01 Dec 1990 Publisher: Random House USA Inc Publication Country: New York, United States Language: English ISBN: 9780449204146 DOWNLOAD: SAYONARA Sayonara PDF Book And along the way, they provide their own insights on whether you should diversify your portfolio (or put your cash somewhere else), whether you should pick your own stocks (or let a pro do it for you), if investing in real estate is really the answer to great wealth, if saving a few pennies here and there really do add up, and much, much more. As Elukin makes clear, the expulsions of Jews from England, France, Spain, and elsewhere were not the inevitable culmination of persecution, but arose from the religious and political expediencies of particular rulers. Their system is simple - 80 of the time you focus on Promoting and 20 on Preparing and Profiting from your efforts. This book is a must-read for people living and working in todays competitive environment. Focusing on the specific needs and challenges of children from birth to three, the book gathers more than a dozen expert contributors with proven expertise in helping children who have or are at risk for developmental delays. Freeman examines the expansion of the global assembly line into the realm of computer-based work, and focuses specifically on the incorporation of young Barbadian women into these high-tech informatics jobs. Chapter 9: The Elements of Exposure and Composition- This chapter gives a primer on the fundamentals of exposure and composition to help you take the best possible photos now that you know how to make all necessary adjustments to your camera settings.