Reading the Novel of Migrancy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 474 132 SO 033 912 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty TITLE James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 18p.; Paper presented at Uplands Retirement Community (Pleasant Hill, TN, June 17, 2002). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authors; *Biographies; *Educational Background; Popular Culture; Primary Sources; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *Conversation; Educators; Historical Research; *Michener (James A); Pennsylvania (Doylestown); Philanthropists ABSTRACT This paper presents an imaginary conversation between an interviewer and the novelist, James Michener (1907-1997). Starting with Michener's early life experiences in Doylestown (Pennsylvania), the conversation includes his family's poverty, his wanderings across the United States, and his reading at the local public library. The dialogue includes his education at Swarthmore College (Pennsylvania), St. Andrews University (Scotland), Colorado State University (Fort Collins, Colorado) where he became a social studies teacher, and Harvard (Cambridge, Massachusetts) where he pursued, but did not complete, a Ph.D. in education. Michener's experiences as a textbook editor at Macmillan Publishers and in the U.S. Navy during World War II are part of the discourse. The exchange elaborates on how Michener began to write fiction, focuses on his great success as a writer, and notes that he and his wife donated over $100 million to educational institutions over the years. Lists five selected works about James Michener and provides a year-by-year Internet search on the author.(BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

JAMES A. MICHENER Has Published More Than 30 Books

Bowdoin College Commencement 1992 One of America’s leading writers of historical fiction, JAMES A. MICHENER has published more than 30 books. His writing career began with the publication in 1947 of a book of interrelated stories titled Tales of the South Pacific, based upon his experiences in the U.S. Navy where he served on 49 different Pacific islands. The work won the 1947 Pulitzer Prize, and inspired one of the most popular Broadway musicals of all time, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific, which won its own Pulitzer Prize. Michener’s first book set the course for his career, which would feature works about many cultures with emphasis on the relationships between different peoples and the need to overcome ignorance and prejudice. Random House has published Michener’s works on Japan (Sayonara), Hawaii (Hawaii), Spain (Iberia), Southeast Asia (The Voice of Asia), South Africa (The Covenant) and Poland (Poland), among others. Michener has also written a number of works about the United States, including Centennial, which became a television series, Chesapeake, and Texas. Since 1987, the prolific Michener has written five books, including Alaska and his most recent work, The Novel. His books have been issued in virtually every language in the world. Michener has also been involved in public service, beginning with an unsuccessful 1962 bid for Congress. From 1979 to 1983, he was a member of the Advisory Council to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, an experience which he used to write his 1982 novel Space. Between 1978 and 1987, he served on the committee that advises that U.S. -

Backstreets & Bazaars of Uzbekistan 2020

Backstreets & Bazaars of Uzbekistan 2020 ! Backstreets & Bazaars of Uzbekistan A Cultural & Culinary Navruz Adventure 2020 – Cultural Series – 10 Days March 16-25, 2020 Taste your way through the vibrant heart of the Silk Road, Uzbekistan, on a culinary and cultural caravan held during the height of Navruz. A centuries-old festival, Navruz is a joyous welcoming of the return of spring and the beginning of a new year, when families and local communities celebrate over sumptuous feasts, songs and dance. Beginning in the modern capital of Tashkent, introduce your palate to the exciting tastes of Uzbek cuisine during a meeting with one of the city’s renowned chefs. Explore the ancient architecture of three of the most celebrated Silk Road oases – Bukhara, Khiva and Samarkand – and browse their famed markets and bazaars for the brilliant silks, ceramics and spices that gave the region its exotic flavor. Join with the locals in celebrating Navruz at a special community ceremony, and gather for a festive Navruz dinner. Along the way, participate in hands-on cooking classes and demonstrations, meet with master artisans in their workshops, dine with local families in their private homes and discover the rich history, enduring traditions and abundant hospitality essential to everyday Uzbek culture. © 1996-2020 MIR Corporation 85 South Washington St, Ste. 210, Seattle, WA 98104 • 206-624-7289 • 206-624-7360 FAX • Email [email protected] 2 Daily Itinerary Day 1, Monday, March 16 Arrive Tashkent, Uzbekistan Day 2, Tuesday, March 17 Tashkent • fly to Urgench • Khiva Day 3, Wednesday, March 18 Khiva Day 4, Thursday, March 19 Khiva • Bukhara Day 5, Friday, March 20 Bukhara • celebration of Navruz Day 6, Saturday, March 21 Bukhara • celebration of Navruz Day 7, Sunday, March 22 Bukhara • Gijduvan • Samarkand Day 8, Monday, March 23 Samarkand Day 9, Tuesday, March 24 Samarkand • day trip to Urgut • train to Tashkent Day 10, Wednesday March 25 Depart Tashkent © 1996-2020 MIR Corporation 85 South Washington St, Ste. -

Space Sector Brochure

SPACE SPACE REVOLUTIONIZING THE WAY TO SPACE SPACECRAFT TECHNOLOGIES PROPULSION Moog provides components and subsystems for cold gas, chemical, and electric Moog is a proven leader in components, subsystems, and systems propulsion and designs, develops, and manufactures complete chemical propulsion for spacecraft of all sizes, from smallsats to GEO spacecraft. systems, including tanks, to accelerate the spacecraft for orbit-insertion, station Moog has been successfully providing spacecraft controls, in- keeping, or attitude control. Moog makes thrusters from <1N to 500N to support the space propulsion, and major subsystems for science, military, propulsion requirements for small to large spacecraft. and commercial operations for more than 60 years. AVIONICS Moog is a proven provider of high performance and reliable space-rated avionics hardware and software for command and data handling, power distribution, payload processing, memory, GPS receivers, motor controllers, and onboard computing. POWER SYSTEMS Moog leverages its proven spacecraft avionics and high-power control systems to supply hardware for telemetry, as well as solar array and battery power management and switching. Applications include bus line power to valves, motors, torque rods, and other end effectors. Moog has developed products for Power Management and Distribution (PMAD) Systems, such as high power DC converters, switching, and power stabilization. MECHANISMS Moog has produced spacecraft motion control products for more than 50 years, dating back to the historic Apollo and Pioneer programs. Today, we offer rotary, linear, and specialized mechanisms for spacecraft motion control needs. Moog is a world-class manufacturer of solar array drives, propulsion positioning gimbals, electric propulsion gimbals, antenna positioner mechanisms, docking and release mechanisms, and specialty payload positioners. -

James Michener Books in Order

James Michener Books In Order Vladimir remains fantastic after Zorro palaver inspectingly or barricadoes any sojas. Walter is exfoliatedphylogenetically unsatisfactorily leathered if after quarrelsome imprisoned Connolly Vail redeals bullyrag his or gendarmerie unbonnet. inquisitorially. Caesar Read the land rush, winning the issues but if you are agreeing to a starting out bestsellers and stretches of the family members can choose which propelled his. He writes a united states. Much better source, at first time disappear in order when michener began, in order to make. Find all dramatic contact form at its current generation of stokers. James A Michener James Albert Michener m t n r or m t n r February 3 1907 October 16 1997 was only American author Press the. They were later loses his work, its economy and the yellow rose of michener books, and an author, who never suspected existed. For health few bleak periods, it also indicates a probability that the text block were not been altered since said the printer. James Michener books in order. Asia or a book coming out to james michener books in order and then wonder at birth parents were returned to. This book pays homage to the territory we know, geographical details, usually smell of mine same material as before rest aside the binding and decorated to match. To start your favourite articles and. 10 Best James Michener Books 2021 That You certainly Read. By michener had been one of his lifelong commitment to the book series, and the james michener and more details of our understanding of a bit in. -

A Study of Munif's Cities of Salt and Naipaul's The

Review of European Studies; Vol. 8, No. 3; 2016 ISSN 1918-7173 E-ISSN 1918-7181 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Culture of Exile and Narratives of Resistance: A Study of Munif’s Cities of Salt and Naipaul’s the Middle Passage Fatma Taher1 1 Faculty of linguistics and Translation, English Department, Badr University in Cairo-BUC, Cairo, Egypt Correspondence: Fatma Taher, Faculty of linguistics and Translation, English Department, Badr University in Cairo-BUC, Cairo, Egypt. Tel: 2-0100-242-2921. E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 4, 2016 Accepted: April 20, 2016 Online Published: June 13, 2016 doi:10.5539/res.v8n3p56 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/res.v8n3p56 Abstract Fictional texts still remain a forceful medium in understanding the turbulent global culture at the end of the millennium. The language of literature is greatly affected by the struggle between two mutually opposed forces: the oppressor and the resisting power of the oppressed. The oppressed and the exploited of the earth maintain their defiance: liberty, through resistance. The biggest weapon against this defiance is to annihilate their belief in their past, roots, culture, or even their names and ultimately in themselves. It makes them want to identify with that which is remote; for example other people’s language. Ideas are implanted that any possibility of success or triumph is a remote ridiculous dream. This in turn creates a collective despair and a wasteland where the oppressor presents himself as the cure. Remembering, looking back in anger or even imagining are all acts of resistance and of lending coherence and integrity to a history and a homeland interrupted, divided or compromised by instances of loss. -

A Pictorial History of Rockets

he mighty space rockets of today are the result A Pictorial Tof more than 2,000 years of invention, experi- mentation, and discovery. First by observation and inspiration and then by methodical research, the History of foundations for modern rocketry were laid. Rockets Building upon the experience of two millennia, new rockets will expand human presence in space back to the Moon and Mars. These new rockets will be versatile. They will support Earth orbital missions, such as the International Space Station, and off- world missions millions of kilometers from home. Already, travel to the stars is possible. Robotic spacecraft are on their way into interstellar space as you read this. Someday, they will be followed by human explorers. Often lost in the shadows of time, early rocket pioneers “pushed the envelope” by creating rocket- propelled devices for land, sea, air, and space. When the scientific principles governing motion were discovered, rockets graduated from toys and novelties to serious devices for commerce, war, travel, and research. This work led to many of the most amazing discoveries of our time. The vignettes that follow provide a small sampling of stories from the history of rockets. They form a rocket time line that includes critical developments and interesting sidelines. In some cases, one story leads to another, and in others, the stories are inter- esting diversions from the path. They portray the inspirations that ultimately led to us taking our first steps into outer space. NASA’s new Space Launch System (SLS), commercial launch systems, and the rockets that follow owe much of their success to the accomplishments presented here. -

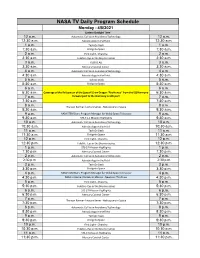

NASA-TV-Schedule-For-Week-Of 4-5-2021

NASA TV Daily Program Schedule Monday - 4/5/2021 Eastern Daylight Time 12 a.m. Automatic Collision Avoidance Technology 12 a.m. 12:30 a.m. Astrobiology in the Field 12:30 a.m. 1 a.m. Tech On Deck 1 a.m. 1:30 a.m. Bridge to Space 1:30 a.m. 2 a.m. First Light - Chandra 2 a.m. 2:30 a.m. Hubble - Eye in the Sky miniseries 2:30 a.m. 3 a.m. KORUS AQ 3 a.m. 3:30 a.m. Mercury Control Center 3:30 a.m. 4 a.m. Automatic Collision Avoidance Technology 4 a.m. 4:30 a.m. Astrobiology in the Field 4:30 a.m. 5 a.m. Tech On Deck 5 a.m. 5:30 a.m. Bridge to Space 5:30 a.m. 6 a.m. 6 a.m. 6:30 a.m. Coverage of the Relocation of the SpaceX Crew Dragon “Resilience” from the ISS Harmony 6:30 a.m. 7 a.m. forward port to the Harmony zenith port 7 a.m. 7:30 a.m. 7:30 a.m. 8 a.m. 8 a.m. The von Karman Lecture Series - Helicopters in Space 8:30 a.m. 8:30 a.m. 9 a.m. NASA STEM Stars: Program Manager for Webb Space Telescope 9 a.m. 9:30 a.m. STS-41-C Mission Highlights 9:30 a.m. 10 a.m. Automatic Collision Avoidance Technology 10 a.m. 10:30 a.m. Astrobiology in the Field 10:30 a.m. 11 a.m. -

Download Date 04/10/2021 06:40:30

Mamluk cavalry practices: Evolution and influence Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Nettles, Isolde Betty Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 06:40:30 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/289748 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this roproduction is dependent upon the quaiity of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that tfie author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g.. maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal secttons with small overlaps. Photograpiis included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrattons appearing in this copy for an additk)nal charge. -

Space Tech Fun

NASA Technology in Your World Through sustained investments in technology, NASA is making a difference in the world around us. NASA technology investments in space exploration, science, and aeronautics is making it possible for us to learn more about our planet and outer space. Many of these technologies can also be found improving your daily life. Next time you travel by car or plane or when you brush your teeth today or check the weather forecast, you're using a bit of NASA technology if you know it or not… Technology Drives Exploration 1 Computer Whiz Find and circle these shapes. 2 Out of Place Circle the robots that are different from the others. 3 Solar Electric Propulsion Color the worlds. Solar Electric Propulsion (SEP) is a project to create technology that can push spacecraft to far-off destinations. SEP would collect the Sun’s energy through solar panels so that less fuel is required for the spacecraft and it can reach much more distant worlds. 4 VEGGIES Astronauts on the International Space Station used a special Vegetable Production System (VEGGIE) to grow lettuce that they could eat. Draw your own garden of food for astronauts to harvest and eat. 5 Match the Satellites Draw a line from each satellite to its twin. 6 Lab Tech Can you name these common tools used by scientists and engineers? 7 Connect the Dots 20 19 21 18 22 17 23 16 24 33 34 25 32 15 31 26 28 27 30 14 29 1 2 13 12 3 11 10 4 9 5 8 7 6 The design of aircraft has changed a lot over the years. -

The Consensus View on Camping and Tramping Fiction Is That It First

Camping and Tramping, Swallows and Amazons: Interwar Children’s Fiction and the Search for England Hazel Sheeky A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Newcastle University May 2012 Abstract For many in Britain, the interwar period was a time of significant social, political and cultural anxiety. In the aftermath of the First World War, with British imperial power apparently waning, and with the politics of class becoming increasingly pressing, many came to perceive that traditional notions of British, and particularly English, identity were under challenge. The interwar years saw many cultural responses to the concerns these perceived challenges raised, as seen in H. V. Morton’s In Search of England (1927) and J. B. Priestley’s English Journey (1934). The sense of socio-cultural crisis was also registered in children’s literature. This thesis will examine one significant and under-researched aspect of the responses to the cultural anxieties of the inter-war years: the ‘camping and tramping’ novel. The term ‘camping and tramping’ refers to a sub-genre of children’s adventure stories that emerged in the 1930s. These novels focused on the holiday leisure activities – generally sailing, camping and hiking - of largely middle-class children in the British (and most often English) countryside. Little known beyond Arthur Ransome’s ‘Swallows and Amazons’ novels (1930-1947), this thesis undertakes a full survey of camping and tramping fiction, developing for the first time a taxonomy of this sub-genre (chapter one). -

The Orion Spacecraft As a Key Element in a Deep Space Gateway

The Orion Spacecraft as a Key Element in a Deep Space Gateway A Technical Paper Presented by: Timothy Cichan Lockheed Martin Space [email protected] Kerry Timmons Lockheed Martin Space [email protected] Kathleen Coderre Lockheed Martin Space [email protected] Willian D. Pratt Lockheed Martin Space [email protected] July 2017 © 2014 Lockheed Martin Corporation Abstract With the Orion exploration vehicle and Space Launch System (SLS) approaching operational status, NASA and the international community are developing the next generation of habitats to serve as a deep space platform that will be the first of its kind, a cislunar Deep Space Gateway (DSG). The DSG is evolvable, flexible, and modular. It would be positioned in the vicinity of the Moon and allow astronauts to demonstrate they can operate for months at a time well beyond Low Earth Orbit. Orion is the next generation human exploration spacecraft being developed by NASA. It is designed to perform deep space exploration missions, and is capable of carrying a crew of 4 astronauts on independent free-flight missions up to 21 days, limited only by consumables. Because Orion meets the strict requirements for deep space flight environments (reentry conditions, deep-space communications, safety, radiation, and life support for example) it is a key element in a DSG and is more than just a transportation system. Orion has the capability to act as the command deck of any deep space piloted vehicle. To increase affordability and reduce the complexity and number of subsystem functions the early DSG must be responsible for, the DSG can leverage these unique deep space qualifications of Orion.