Evolutions of "Paradise": Japanese Tourist Discourse About Hawaii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 474 132 SO 033 912 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty TITLE James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 18p.; Paper presented at Uplands Retirement Community (Pleasant Hill, TN, June 17, 2002). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authors; *Biographies; *Educational Background; Popular Culture; Primary Sources; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *Conversation; Educators; Historical Research; *Michener (James A); Pennsylvania (Doylestown); Philanthropists ABSTRACT This paper presents an imaginary conversation between an interviewer and the novelist, James Michener (1907-1997). Starting with Michener's early life experiences in Doylestown (Pennsylvania), the conversation includes his family's poverty, his wanderings across the United States, and his reading at the local public library. The dialogue includes his education at Swarthmore College (Pennsylvania), St. Andrews University (Scotland), Colorado State University (Fort Collins, Colorado) where he became a social studies teacher, and Harvard (Cambridge, Massachusetts) where he pursued, but did not complete, a Ph.D. in education. Michener's experiences as a textbook editor at Macmillan Publishers and in the U.S. Navy during World War II are part of the discourse. The exchange elaborates on how Michener began to write fiction, focuses on his great success as a writer, and notes that he and his wife donated over $100 million to educational institutions over the years. Lists five selected works about James Michener and provides a year-by-year Internet search on the author.(BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Reading the Novel of Migrancy

Reading the Novel of Migrancy Sheri-Marie Harrison Abstract This essay argues that novels like Marlon James’s A Brief History of Seven Killings, Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer, Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, and Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West exemplify a new form of the novel that does not depend on national identification, but is instead organized around the transnational circulation of people and things in a manner that parallels the de- regulated flow of neoliberal capital. In their literal depiction of the movement of people across borders, these four very different novels collectively address the circulation of codes, tropes, and strategies of representation for particular ethnic and racial groups. Moreover, they also address, at the level of critique, the rela- tionship of such representational strategies to processes of literary canonization. The metafictional and self-reflexive qualities of James’s and Nguyen’s novels con- tinually draw the reader’s attention to the politics of reading and writing, and in the process they thwart any easy conclusions about what it means to write about conflicts like the Vietnam war or the late 1970s in Jamaica. Likewise, despite their different settings Hamid’s Exit West and Whitehead’s Underground Railroad are alike in that they are both about the movement of stateless people across borders and both push the boundaries of realism itself by employing non-realistic devices as a way of not representing travel across borders. In pointing to, if not quite il- luminating, the “dark places of the earth,” the novel of migrancy thus calls into existence, without really representing, conditions for a global framework that does not yet exist. -

JAMES A. MICHENER Has Published More Than 30 Books

Bowdoin College Commencement 1992 One of America’s leading writers of historical fiction, JAMES A. MICHENER has published more than 30 books. His writing career began with the publication in 1947 of a book of interrelated stories titled Tales of the South Pacific, based upon his experiences in the U.S. Navy where he served on 49 different Pacific islands. The work won the 1947 Pulitzer Prize, and inspired one of the most popular Broadway musicals of all time, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific, which won its own Pulitzer Prize. Michener’s first book set the course for his career, which would feature works about many cultures with emphasis on the relationships between different peoples and the need to overcome ignorance and prejudice. Random House has published Michener’s works on Japan (Sayonara), Hawaii (Hawaii), Spain (Iberia), Southeast Asia (The Voice of Asia), South Africa (The Covenant) and Poland (Poland), among others. Michener has also written a number of works about the United States, including Centennial, which became a television series, Chesapeake, and Texas. Since 1987, the prolific Michener has written five books, including Alaska and his most recent work, The Novel. His books have been issued in virtually every language in the world. Michener has also been involved in public service, beginning with an unsuccessful 1962 bid for Congress. From 1979 to 1983, he was a member of the Advisory Council to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, an experience which he used to write his 1982 novel Space. Between 1978 and 1987, he served on the committee that advises that U.S. -

Space Sector Brochure

SPACE SPACE REVOLUTIONIZING THE WAY TO SPACE SPACECRAFT TECHNOLOGIES PROPULSION Moog provides components and subsystems for cold gas, chemical, and electric Moog is a proven leader in components, subsystems, and systems propulsion and designs, develops, and manufactures complete chemical propulsion for spacecraft of all sizes, from smallsats to GEO spacecraft. systems, including tanks, to accelerate the spacecraft for orbit-insertion, station Moog has been successfully providing spacecraft controls, in- keeping, or attitude control. Moog makes thrusters from <1N to 500N to support the space propulsion, and major subsystems for science, military, propulsion requirements for small to large spacecraft. and commercial operations for more than 60 years. AVIONICS Moog is a proven provider of high performance and reliable space-rated avionics hardware and software for command and data handling, power distribution, payload processing, memory, GPS receivers, motor controllers, and onboard computing. POWER SYSTEMS Moog leverages its proven spacecraft avionics and high-power control systems to supply hardware for telemetry, as well as solar array and battery power management and switching. Applications include bus line power to valves, motors, torque rods, and other end effectors. Moog has developed products for Power Management and Distribution (PMAD) Systems, such as high power DC converters, switching, and power stabilization. MECHANISMS Moog has produced spacecraft motion control products for more than 50 years, dating back to the historic Apollo and Pioneer programs. Today, we offer rotary, linear, and specialized mechanisms for spacecraft motion control needs. Moog is a world-class manufacturer of solar array drives, propulsion positioning gimbals, electric propulsion gimbals, antenna positioner mechanisms, docking and release mechanisms, and specialty payload positioners. -

A Pictorial History of Rockets

he mighty space rockets of today are the result A Pictorial Tof more than 2,000 years of invention, experi- mentation, and discovery. First by observation and inspiration and then by methodical research, the History of foundations for modern rocketry were laid. Rockets Building upon the experience of two millennia, new rockets will expand human presence in space back to the Moon and Mars. These new rockets will be versatile. They will support Earth orbital missions, such as the International Space Station, and off- world missions millions of kilometers from home. Already, travel to the stars is possible. Robotic spacecraft are on their way into interstellar space as you read this. Someday, they will be followed by human explorers. Often lost in the shadows of time, early rocket pioneers “pushed the envelope” by creating rocket- propelled devices for land, sea, air, and space. When the scientific principles governing motion were discovered, rockets graduated from toys and novelties to serious devices for commerce, war, travel, and research. This work led to many of the most amazing discoveries of our time. The vignettes that follow provide a small sampling of stories from the history of rockets. They form a rocket time line that includes critical developments and interesting sidelines. In some cases, one story leads to another, and in others, the stories are inter- esting diversions from the path. They portray the inspirations that ultimately led to us taking our first steps into outer space. NASA’s new Space Launch System (SLS), commercial launch systems, and the rockets that follow owe much of their success to the accomplishments presented here. -

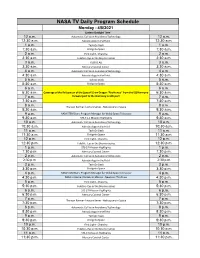

NASA-TV-Schedule-For-Week-Of 4-5-2021

NASA TV Daily Program Schedule Monday - 4/5/2021 Eastern Daylight Time 12 a.m. Automatic Collision Avoidance Technology 12 a.m. 12:30 a.m. Astrobiology in the Field 12:30 a.m. 1 a.m. Tech On Deck 1 a.m. 1:30 a.m. Bridge to Space 1:30 a.m. 2 a.m. First Light - Chandra 2 a.m. 2:30 a.m. Hubble - Eye in the Sky miniseries 2:30 a.m. 3 a.m. KORUS AQ 3 a.m. 3:30 a.m. Mercury Control Center 3:30 a.m. 4 a.m. Automatic Collision Avoidance Technology 4 a.m. 4:30 a.m. Astrobiology in the Field 4:30 a.m. 5 a.m. Tech On Deck 5 a.m. 5:30 a.m. Bridge to Space 5:30 a.m. 6 a.m. 6 a.m. 6:30 a.m. Coverage of the Relocation of the SpaceX Crew Dragon “Resilience” from the ISS Harmony 6:30 a.m. 7 a.m. forward port to the Harmony zenith port 7 a.m. 7:30 a.m. 7:30 a.m. 8 a.m. 8 a.m. The von Karman Lecture Series - Helicopters in Space 8:30 a.m. 8:30 a.m. 9 a.m. NASA STEM Stars: Program Manager for Webb Space Telescope 9 a.m. 9:30 a.m. STS-41-C Mission Highlights 9:30 a.m. 10 a.m. Automatic Collision Avoidance Technology 10 a.m. 10:30 a.m. Astrobiology in the Field 10:30 a.m. 11 a.m. -

Almanac ■ Guide to Air Force Installations Worldwide

USAFAlmanac ■ Guide to Air Force Installations Worldwide Major Installations Note: A major installation is an Air Force Base, Air Andrews AFB, Md. 20762-5000; 10 mi. SE of 4190th Wing, Pisa, Italy; 31st Munitions Support Base, Air Guard Base, or Air Reserve Base that Washington, D. C. Phone (301) 981-1110; DSN Sqdn., Ghedi AB, Italy; 4190th Air Base Sqdn. serves as a self-supporting center for Air Force 858-1110. AMC base. Gateway to the nation’s (Provisional), San Vito dei Normanni, Italy; 496th combat, combat support, or training operations. capital and home of Air Force One. Host wing: 89th Air Base Sqdn., Morón AB, Spain; 731st Munitions Active-duty, Air National Guard (ANG), or Air Force Airlift Wing. Responsible for Presidential support Support Sqdn., Araxos AB, Greece; 603d Air Control Reserve Command (AFRC) units of wing size or and base operations; supports all branches of the Sqdn., Jacotenente, Italy; 48th Intelligence Sqdn., larger operate the installation with all land, facili- armed services, several major commands, and Rimini, Italy. One of the oldest Italian air bases, ties, and support needed to accomplish the unit federal agencies. The wing also hosts Det. 302, dating to 1911. USAF began operations in 1954. mission. There must be real property accountability AFOSI; Hq. Air Force Flight Standards Agency; Area 1,467 acres. Runway 8,596 ft. Altitude 413 through ownership of all real estate and facilities. AFOSI Academy; Air National Guard Readiness ft. Military 3,367; civilians 1,102. Payroll $156.9 Agreements with foreign governments that give Center; 113th Wing (D. C. -

WIRELESS and EMPIRE AMBITION Wireless Telegraphy/Telephony And

WIRELESS AND EMPIRE AMBITION Wireless telegraphy/telephony and radio broadcasting in the British Solomon Islands Protectorate, South-West Pacific (1914-1947): political, social and developmental perspectives Martin Lindsay Hadlow Master of Arts in Mass Communications, University of Leicester, 2003 Honorary Doctorate, Kazakh State National University (named after Al-Farabi), 1997 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2016 School of Communication and Arts Abstract This thesis explores the establishment of wireless technology (telegraphy, telephony and broadcasting) in the British Solomon Islands Protectorate (BSIP), South-West Pacific and analyses its application as a political, social and cultural tool during the colonial years spanning the first half of the 20th century. While wireless seemed a ready-made technology for the Pacific, given its capability as a medium to transmit and receive signals instantly across vast expanses of ocean, the colonial civil servants of Britain’s Fiji-based regional headquarters, the Western Pacific High Commission (WPHC) in Suva, were slow to understand its strategic value. Conservative attitudes to governance, combined with a confidence born of Imperial rule, not to mention bureaucratic inertia and an almost complete lack of understanding of the new medium by a reluctant administration, aligned to cause obfuscation, delay and frustration. In the British Solomon Islands Protectorate, one of the most geographically remote ‘fragments of Empire’, pressures from the commercial sector (primarily planters and traders), the religious community (mission stations in remote locations), keen amateur experimenters (expatriate businessmen), wireless sales companies (Marconi and AWA Ltd.), not to mention the declaration of World War I itself, all intervened to bring about change to the stultified regulatory environment then pertaining and to ensure the introduction of wireless technology in its multitude of iterations. -

(HU) January 19, 2009 Interviewer: Brian Niiya

JAPANESE CULTURAL CENTER OF HAWAI‘I ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW with HARRY URATA (HU) January 19, 2009 Interviewer: Brian Niiya (BN) Notes: Double parentheses ((?)) denote unclear sentences or words. Notes in brackets [ ] are added by the translator for clarification purposes. BN: We’re here at the Japanese Cultural Center on January 19, 2009 with Mr. Harry Urata and we’re going to ask him a life history with him and I guess we’ll start maybe with your parents. Maybe you could tell me their names and what you know about where they were from and what led them to come to Hawaii as far as, based on what you know. HU: Can you speak louder? I have a hard time hearing now. BN: I wonder if you could tell us about your parents—their names and what you know about where they were from and why they came to Hawaii. HU: My father’s name is Fukutaro Urata. My mother and he got married in Kumamoto before they came to Hawaii. That was, I think, I don’t remember exactly when but then they settled in Kukui Street, where I live right now, and they started a vegetable store, small one, very small. Then I was born there but when I was two years old, my father had an accident, car accident, at Nuuanu Pali. I think he was the first victim of Japanese immigrants with a car accident so came out in a big write-up in Hawaii Hochi and Nippu Jiji. I still have the Nippu Jiji one. -

2007-2008 Annual Report

07_08 ANNUAL REPORT 07_08 ANNUAL REPORT LETTER FROM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Dear Friends: The 2007-08 season at YBCA has once again proven to be one of Not to be overlooked, the financial figures that are here will dem- significant accomplishment. onstrate the fiscal responsibility that is the hallmark of our work at As you will see by looking through this annual report, our artistic YBCA. We take very seriously the responsibility invested in us not endeavors continue unabated. While it is always difficult to select only by the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency but also by the only a few highlights from any given season, I would certainly be foundations, individuals and corporations who believe in the work remiss if I did not point to exhibitions such as The Missing Peace: that we do and make their contributions accordingly. I am particularly Artists Consider the Dalai Lama, Anna Halprin: At the Origin of proud to note a major gift from the Novellus Systems, Inc. to name Performance and Dark Matters: Artists See the Impossible, as true the theater at YBCA. This is an amazing gift that will come to us over achievements for YBCA. Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, the next ten years and will be invested in programs at YBCA. Faustin Linyekula and Ilkhom Theatre brought us extraordinary I can say without hesitation that the staff of YBCA are dedicated, performance from around the world and Marc Bamuthi Joseph, a committed and enthusiastic about the work that we do. Without their Bay Area artist with whom we have a long-standing relationship, extraordinary effort, we would not be able to accomplish as much as opened his new piece, the break/s, here at YBCA and it has gone we do. -

DENSHO PUBLICATIONS Articles by Kelli Y

DENSHO PUBLICATIONS Articles by Kelli Y. Nakamura Kapiʻolani Community College Spring 2016 Byodo-In by Rocky A / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 The articles, by Nakamura, Kelli Y., are licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 by rights owner Densho Table of Contents 298th/299th Infantry ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Alien Enemies Act of 1798 ........................................................................................................................... 3 Americans of Japanese Ancestry: A Study of Assimilation in the American Community (book) ................. 6 By: Kelli Y. Nakamura ................................................................................................................................. 6 Cecil Coggins ................................................................................................................................................ 9 Charles F. Loomis ....................................................................................................................................... 11 Charles H. Bonesteel ................................................................................................................................... 13 Charles Hemenway ..................................................................................................................................... 15 Dan Aoki .................................................................................................................................................... -

Program 1..169

The 92nd Annual Meeting of CSJ Program tein Synthesis Using Peptide Thioesters as Building Blocks(IPR, Osaka Room S1 Univ.)AIMOTO, Saburo(15:20~16:20) 4th Bldg., Section B J11 Room S2 CSJ Award Presentation 4th Bldg., Section B J21 Sunday, March 25, AM Chair: KOBAYASHI, Hayao(11:00~12:00) CSJ Award Presentation 1S1- 01 CSJ Award Presentation Edge State of Nanographene and its Electronic and Magnetic Properties(Tokyo Institute of Technology) Monday, March 26, AM ENOKI, Toshiaki(11:00~12:00) Chair: SHIROTA, Yasuhiko(10:00~11:00) 2S2- 01 CSJ Award Presentation Creation of Functional Supramole- cular Polymers through Molecular Recognition(Grad. Sch. Sci., Osaka Monday, March 26, AM Univ.)HARADA, Akira(10:00~11:00) Chair: TATSUMI, Kazuyuki(10:00~11:00) 2S1- 01 CSJ Award Presentation Pioneering and Developing Studies Chair: HIYAMA, Tamejiro(11:10~12:10) on Structural Chemistry of Fluctuations(Grad. Sch. Adv. Integration Sci., 2S2- 02 CSJ Award Presentation Studies on the Chemistry of Low- Chiba Univ.)NISHIKAWA, Keiko(10:00~11:00) Coordinate Organosilicon and Heavier Group 14 Element Compounds(Grad. Sch. Pure Appl. Sci., Univ. of Tsukuba)SEKIGUCHI, Akira(11:10~ Chair: TANAKA, Kenichiro(11:10~12:10) 12:10) 2S1- 02 CSJ Award Presentation Development of Photocatalysts for Overall Water Splitting(The Univ. of Tokyo)DOMEN, Kazunari(11:10~ 12:10) Frontier of Plasmonic Photochemistry Monday, March 26, PM New Challenges in Bioinorganic Chemistry - Chair: MURAKOSHI, Kei(13:30~14:50) Towards New Development of Bio-Related 2S2- 03 Special Lecture Opening Remarks(RIES, Hokkaido Univ.) Chemistry MISAWA, Hiroaki(13:30~13:40) 2S2- 04 Monday, March 26, PM Special Lecture Tuning of surface plasmon resonance wave- lengths by structural control of inorganic nano particles(ICR, Kyoto Univ.) Chair: ITOH, Shinobu(13:30~14:50) TERANISHI, Toshiharu(13:40~14:15) 2S1- 03 Special Lecture Artificial Photosynthesis for Production of 2S2- 05 Special Lecture Fabrication of Metal-Semiconductor Nano- Chemical Fuels(Grad.