1 Summary by the Secretary-General of the Report of the United Nations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education in Danger

Education in Danger Monthly News Brief December Attacks on education 2019 The section aligns with the definition of attacks on education used by the Global Coalition to Protect Education under Attack (GCPEA) in Education under Attack 2018. Africa This monthly digest compiles reported incidents of Burkina Faso threatened or actual violence 10 December 2019: In Bonou village, Sourou province, suspected affecting education. Katiba Macina (JNIM) militants allegedly attacked a lower secondary school, assaulted a guard and ransacked the office of the college It is prepared by Insecurity director. Source: AIB and Infowakat Insight from information available in open sources. 11 December 2019: Tangaye village, Yatenga province, unidentified The listed reports have not been gunmen allegedly entered an unnamed high school and destroyed independently verified and do equipment. The local town hall was also destroyed in the attack. Source: not represent the totality of Infowakat events that affected the provision of education over the Cameroon reporting period. 08 December 2019: In Bamenda city, Mezam department, Nord-Ouest region, unidentified armed actors allegedly abducted around ten Access data from the Education students while en route to their campus. On 10 December, the in Danger Monthly News Brief on HDX Insecurity Insight. perpetrators released a video stating the students would be freed but that it was a final warning to those who continue to attend school. Visit our website to download Source: 237actu and Journal Du Cameroun previous Monthly News Briefs. Mali Join our mailing list to receive 05 December 2019: Near Ansongo town, Gao region, unidentified all the latest news and resources gunmen reportedly the director of the teaching academy in Gao was from Insecurity Insight. -

Syria: "Torture Was My Punishment": Abductions, Torture and Summary

‘TORTURE WAS MY PUNISHMENT’ ABDUCTIONS, TORTURE AND SUMMARY KILLINGS UNDER ARMED GROUP RULE IN ALEPPO AND IDLEB, SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Cover photo: Armed group fighters prepare to launch a rocket in the Saif al-Dawla district of the Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons northern Syrian city of Aleppo, on 21 April 2013. (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Miguel Medina/AFP/Getty Images https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2016 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/4227/2016 July 2016 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 METHODOLOGY 7 1. BACKGROUND 9 1.1 Armed group rule in Aleppo and Idleb 9 1.2 Violations by other actors 13 2. ABDUCTIONS 15 2.1 Journalists and media activists 15 2.2 Lawyers, political activists and others 18 2.3 Children 21 2.4 Minorities 22 3. -

QRCS Delivers Medical Aid to Hospitals in Aleppo, Idlib

QRCS Delivers Medical Aid to Hospitals in Aleppo, Idlib May 3rd, 2016 ― Doha: Qatar Red Crescent Society (QRCS) is proceeding with its support of the medical sector in Syria, by providing medications, medical equipment, and fuel to help health facilities absorb the increasing numbers of injuries, amid deteriorating health conditions countrywide due to the conflict. Lately, QRCS personnel in Syria procured 30,960 liters of fuel to operate power generators at the surgical hospital in Aqrabat, Idlib countryside. These $17,956 supplies will serve the town's 100,000 population and 70,000 internally displaced people (IDPs). In coordination with the Health Directorate in Idlib, QRCS is operating and supporting the hospital with fuel, medications, medical consumables, and operational costs. Working with a capacity of 60 beds and four operating rooms, the hospital is specialized in orthopedics and reconstructive procedures, in addition to general medicine and dermatology clinics. In western Aleppo countryside, QRCS personnel delivered medical consumables and serums worth $2,365 to the health center of Kafarnaha, to help reduce the pressure on the center's resources, as it is located near to the clash frontlines. Earlier, a needs assessment was done to identify the workload and shortfalls, and accordingly, the needed types of supplies were provided to serve around 1,500 patients from the local community and IDPs. In relation to its $200,000 immediate relief intervention launched last week, QRCS is providing medical supplies, fuel, and food aid; operating AlSakhour health center for 100,000 beneficiaries in Aleppo City, at a cost of $185,000; securing strategic medical stock for the Health Directorate; providing the municipal council with six water tankers to deliver drinking water to 350,000 inhabitants at a cost of $250,000; arranging for more five tankers at a cost of $500,000; providing 1,850 medical kits, 28,000 liters of fuel, and water purification pills; and supplying $80,000 worth of food aid. -

Idleb Governorate, Ariha District April 2018

Humanitarian Situation Overview in Syria (HSOS): Sub-district Factsheets Idleb GovernorateGovernorate, Ariha District JanuaryApril 2018 Introduction This multi-sectoral needs assessment is part of a monthly data collection exercise which aims to gather information about needs and the humanitarian situation inside Syria. The factsheets present information collected in MayFebruary 2018, 2018, referring referring to the to situation the situation in April in ALEPPO January2018. 2018. These factsheets present information at the community level for 21three sub-districts sub-districts in in Idleb Ariha governorate.district in Idleb Selected governorate. key indicatorsSelected keyfor IDLEB theindicators following for sectorsthe following are included sectors inare the included factsheets: in the displacement, factsheets: shelter,displacement, non-food shelter, items non-food(NFIs), health, items food(NFIs), security, health, water food sanitation security, andwater hygiene sanitation (WASH) and hygiene and education. (WASH) The and factsheets education. do The not factsheets cover the Mhambal Ariha entiredo not rangecover theof indicators entire range gathered of indicators in the gathered questionnaire. in the questionnaire. Ehsem For full visualisation of all indicators collected, please see the SIMAWG Needs Identification Dynamic Reporting Tool, available here: http://www.reach-info.org/syr/simawg/.https://reach3.cern.ch/simawg/Default.aspx. LATTAKIA Methodology and limitations HAMA These findings areare basedbased onon datadata collected collected both directly directly (in andTurkey) remotely from (inKey Turkey) Informants from (KIs)Key Informants residing in residing the communities in the communities assessed. assessed. Information waswas collectedcollected from from KIs Key in 60Informants communities in 143 in 3communities sub districts inof 21Idleb sub-districts governorate. of IdlebFor eachgovernorate. -

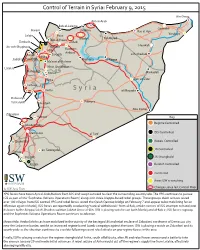

Control of Terrain in Syria: February 9, 2015

Control of Terrain in Syria: February 9, 2015 Ain-Diwar Ayn al-Arab Bab al-Salama Qamishli Harem Jarablus Ras al-Ayn Yarubiya Salqin Azaz Tal Abyad Bab al-Hawa Manbij Darkush al-Bab Jisr ash-Shughour Aleppo Hasakah Idlib Kuweiris Airbase Kasab Saraqib ash-Shadadi Ariha Jabal al-Zawiyah Maskana ar-Raqqa Ma’arat al-Nu’man Latakia Khan Sheikhoun Mahardeh Morek Markadeh Hama Deir ez-Zour Tartous Homs S y r i a al-Mayadin Dabussiya Palmyra Tal Kalakh Jussiyeh Abu Kamal Zabadani Yabrud Key Regime Controlled Jdaidet-Yabus ISIS Controlled Damascus al-Tanf Quneitra Rebels Controlled as-Suwayda JN Controlled Deraa Nassib JN Stronghold Jizzah Kurdish Controlled Contested Areas ISW is watching Changes since last Control Map by ISW Syria Team YPG forces have taken Ayn al-Arab/Kobani from ISIS and swept outward to clear the surrounding countryside. The YPG continues to pursue ISIS as part of the “Euphrates Volcano Operations Room,” along with three Aleppo-based rebel groups. These groups claim to have seized over 100 villages from ISIS control. YPG and rebel forces seized the Qarah Qawzaq bridge on February 7 and appear to be mobilizing for an oensive against Manbij. ISIS forces are reportedly conducting “tactical withdrawals” from al-Bab, amidst rumors of ISIS attempts to hand over its bases to the Aleppo Sala Jihadist coalition Jabhat Ansar al-Din. ISW is placing watches on both Manbij and al-Bab as ISIS forces regroup and the Euphrates Volcano Operations Room continues to advance. Meanwhile, Hezbollah forces have mobilized in the vicinity of the besieged JN and rebel enclave of Zabadani, northwest of Damascus city near the Lebanese border, amidst an increased regime barrel bomb campaign against the town. -

WHEAT VALUE CHAIN ASSESSMENT North West - Syria June 2020

WHEAT VALUE CHAIN ASSESSMENT North West - Syria June 2020 Shafak & MH Europe Organizations Contents 1 Humanitarian Needs Overview ............................................................................................................................ 2 2 Methodology and Approach................................................................................................................................... 3 3 Abstract ...................................................................................................................................................................... 4 4 Locations .................................................................................................................................................................... 6 5 Assessment Findings ................................................................................................................................................ 7 5.1 Affected population demographics: ............................................................................................. 7 5.2 Affected people main occupation: ................................................................................................ 7 5.3 Agriculture land-farmers: ................................................................................................................... 9 5.4 farmers Challenges: ............................................................................................................................. 10 5.5 Main Cultivated Crops: ...................................................................................................................... -

S/2019/321 Security Council

United Nations S/2019/321 Security Council Distr.: General 16 April 2019 Original: English Implementation of Security Council resolutions 2139 (2014), 2165 (2014), 2191 (2014), 2258 (2015), 2332 (2016), 2393 (2017), 2401 (2018) and 2449 (2018) Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is the sixtieth submitted pursuant to paragraph 17 of Security Council resolution 2139 (2014), paragraph 10 of resolution 2165 (2014), paragraph 5 of resolution 2191 (2014), paragraph 5 of resolution 2258 (2015), paragraph 5 of resolution 2332 (2016), paragraph 6 of resolution 2393 (2017),paragraph 12 of resolution 2401 (2018) and paragraph 6 of resolution 2449 (2018), in the last of which the Council requested the Secretary-General to provide a report at least every 60 days, on the implementation of the resolutions by all parties to the conflict in the Syrian Arab Republic. 2. The information contained herein is based on data available to agencies of the United Nations system and obtained from the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic and other relevant sources. Data from agencies of the United Nations system on their humanitarian deliveries have been reported for February and March 2019. II. Major developments Box 1 Key points: February and March 2019 1. Large numbers of civilians were reportedly killed and injured in Baghuz and surrounding areas in south-eastern Dayr al-Zawr Governorate as a result of air strikes and intense fighting between the Syrian Democratic Forces and Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant. From 4 December 2018 through the end of March 2019, more than 63,500 people were displaced out of the area to the Hawl camp in Hasakah Governorate. -

The Aid in Danger Monthly News Brief – June 2019 Page 1 Ngos of Demanding Bribes from Them for Their Repatriation to Somalia and Other Services

Aid in Danger Monthly News Brief June 2019 This monthly digest Safety, security and access incidents comprises threats and Insecurity affecting aid workers and aid delivery incidents of violence affecting the delivery of Africa humanitarian assistance. Cameroon Throughout June 2019: In unspecified Anglophone locations, armed separatists set fire to an unspecified number of shipments of food, It is prepared by medicine and bedding escorted by the Cameroon Armed Forces, Insecurity Insight from claiming that they will never accept aid from the Cameroonian information available in Government. Source: VOA open sources. Central African Republic 25 June 2019: In Batangafo, Ouham prefecture, an INGO national aid All decisions made, on the worker was reportedly assaulted in a home invasion by armed anti- basis of, or with Balaka militants. Four other occupants were robbed of their mobile consideration to, such phones, cash, and other items. The aid worker received medical information remains the treatment, and the perpetrators were handed over to MINUSCA by a responsibility of their local anti-Balaka leader. Source: AWSD1 respective organisations. Democratic Republic of the Congo 05 June 2019: In Lubero, North Kivu, suspected Mai-Mai militants Subscribe here to receive kidnapped two NGO workers. No further details specified. Source: monthly reports on ACLED2 insecurity affecting the delivery of aid. 25 June 2019: In North Kivu, Katwiguru II, an unidentified armed group kidnapped an aid worker from the INGO Caritas. No further details specified. Source: ACLED2 Visit our website to download previous Aid in Eritrea Danger Monthly News Throughout June 2019: The Eritrean Government continued to deny Briefs. the Human Rights Council’s Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Eritrea access to Eritrea. -

Latakia - Ariha Highway Syria

LATAKIA - ARIHA HIGHWAY SYRIA CCL Client: Mohammed Abdulmohsim Al Kharafi & Sons (MAK Group) Consultant/Architect: Khatib & Alami Project Date: 2009 The Latakia - Ariha Highway in Syria is a were the mobilisation of the launching gantry itself and the subsequent demobilisation, both of which had to be carried 98 km-long road connecting the districts out 16 times. Difficulties were also created by the geometry of Latakia, Aleppo and Idlib. Linking the of some of the viaducts, which included longitudinal slopes Syrian coastal areas with the internal of 6% and in-place curvature. regions, the new highway is designed The length of the precast beams also caused problems, to relieve traffic congestion and provide with regard to transportation. The precast beams were cast in three seperate segments to facilitate transportation from much improved mobility throughout the the precast yard to the construction location. Once on site, region. they were assembled and the post-tensioning was carried out behind the abutment of the related bridge. They were This six-lane expressway includes 16 viaducts, each then installed using the launching gantry. containing post-tensioned beams 36 metres in length. In total, 1300 post-tensioned beams were installed. CCL CCL’s ability to successfully overcome all of the above was involved in the precasting, the post-tensioning and challenges resulted in the construction process being the installation of the beams. In order to carry out the completed on schedule and with maximum efficiency. installation successfully, a launching girder was used. The project, which was completed in 2008, presented many challenges for the company. -

February 2019 Fig

HEALTH CLUSTER BULLETIN February 2019 Fig. AIDoctors providing physiotherapy services Turkey Cross Border Fig. AIDoctors providing Physical Therapy sessions. Emergency type: complex emergency Reporting period: 01.02.2019 to 28.02.2019 13.2 MILLION* 2.9 MILLION* 3.58 MILLION 3** ATTACKS PEOPLE IN NEED OF HEALTH PIN IN SYRIAN REFUGGES AGAINST HEALTH CARE HEALTH ASSISTANCE NWS HRP2019 IN TURKEY (**JAN-FEB 2019) (A* figures are for the Whole of Syria HRP 2019 (All figures are for the Whole of Syria) HIGHLIGHTS GAZIANTEP HEALTH CLUSTER The funds suspension from the governments of 116 HEALTH CLUSTER MEMBERS Germany and France in humanitarian activities in MEDICINES DELIVERED1 the health sector was lifted for some NGOs and TREATMENT COURSES FOR COMMON 460,000 the programs with humanitarian activities will DISEASES resume. Although suspension was lifted, the FUNCTIONAL HEALTH FACILITIES HERAMS NGOs must adhere to several additional FUNCTIONING FIXED PRIMARY HEALTH measures to allow full resumption of the 173 CARE FACILITIES humanitarian activities. 85 FUNCTIONING HOSPITALS The Azaz Mental Health Asylum Hospital will stop 80 MOBILE CLINICS operating end of February 2019. The hospital, HEALTH SERVICES2 supported by PAC, is currently funded by King 905,502 CONSULTATIONS Salman Foundation. The mental health patients 9,320 DELIVERIES ASSISTED BY A SKILLED of this hospital should be transported to Aleppo ATTENDANT or Damascus City. An Exit Strategy/Transfer plan 8,489 REFERRALS is not clear yet but been develop. 977,744 MEDICAL PROCEDURES th On 26 February, local sources reported that the 37,310 TRAUMA CASES SUPPORTED SSG issued a new circular that all the NGOs 2,387 NEW CONFLICT RELATED TRAUMA CASES vehicles and ambulances must get a mission VACCINATION order from the SSG to be able to cross from Idleb 8,264 CHILDREN AGED ˂5 VACCINATED3 to Afrin and Northern Aleppo. -

S/PV.8449 the Situation in the Middle East, Including the Palestinian Question 22/01/2019

United Nations S/ PV.8449 Security Council Provisional Seventy-fourth year 8449th meeting Tuesday, 22 January 2019, 10 a.m. New York President: Mr. Singer Weisinger/Mr. Trullols ................... (Dominican Republic) Members: Belgium ....................................... Mr. Pecsteen de Buytswerve China ......................................... Mr. Ma Zhaoxu Côte d’Ivoire ................................... Mr. Ipo Equatorial Guinea ............................... Mr. Ndong Mba France ........................................ Mr. Delattre Germany ...................................... Mr. Heusgen Indonesia. Mrs. Marsudi Kuwait ........................................ Mr. Alotaibi Peru .......................................... Mr. Meza-Cuadra Poland ........................................ Ms. Wronecka Russian Federation ............................... Mr. Nebenzia South Africa ................................... Mr. Matjila United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland .. Ms. Pierce United States of America .......................... Mr. Cohen Agenda The situation in the Middle East, including the Palestinian question . This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the translation of speeches delivered in other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original languages only. They should be incorporated in a copy of the record and sent under the signature of a member of the delegation concerned to the Chief of the Verbatim Reporting Service, room U-0506 ([email protected]). Corrected records will be reissued electronically on the Official Document System of the United Nations (http://documents.un.org). 19-01678 (E) *1901678* S/PV.8449 The situation in the Middle East, including the Palestinian question 22/01/2019 The meeting was called to order at 10.05 a.m. with the provisional rules of procedure and previous practice in this regard. Expression of sympathy in connection with and There being no objection, it is so decided. -

Seven Years of Crisis Islamic Relief’S Humanitarian Response in Syria 2012-2017

SEVEN YEARS OF CRISIS ISLAMIC RELIEF’S HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE IN SYRIA 2012-2017 1 ISLAMIC RELIEF USA Islamic Relief USA has been serving humanity for the past 25 years. With an active presence in over 30 countries across the globe, we strive to work together for a better world for the three billion people still living in poverty. Since we received our first donation in 1993, we Our Values have helped millions of the world’s poorest and We remain guided by the timeless values and most vulnerable people. Inspired by the Islamic teachings of the Qur’an and the prophetic faith and guided by our values, we believe that example (Sunnah), most specifically: we have a duty to help those less fortunate – regardless of race, political affiliation, gender, or Sincerity (Ikhlas) belief. In responding to poverty and suffering, our efforts Our projects provide vulnerable people with are driven by sincerity to God and the need to fulfil access to vital services. We protect communities our obligations to humanity. from disasters and deliver life-saving emergency aid. We provide lasting routes out of poverty, and Excellence (Ihsan) empower vulnerable people to transform their lives and their communities. Our actions in tackling poverty are marked by excellence in our operations and the conduct Our Mission through which we help the people we serve. Islamic Relief USA provides relief and Compassion (Rahma) development in a dignified manner regardless of We believe the protection and well-being of every gender, race, or religion, and works to empower life is of paramount importance and we shall join individuals in their communities and give them a with other humanitarian actors to act as one in voice in the world.