ABSTRACT This Thesis Employs the Theory of Reflexive Individualization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Application of Talent Management Theories to the Prevention of "Brain Drain" in China

Dinh Loc, Nguyen The Application of Talent Management Theories to the Prevention of "Brain Drain" in China Helsinki Metropolia University of Applied Sciences Metropolia Business School Bachelor of Business Administration International Business and Logistics Bachelor Thesis 1406653 03 November 2017 Author(s) Dinh Loc Nguyen Title The Application of Talent Management Theories to the Prevention of "Brain Drain" in China Number of pages 59 pages + 2 appendices Date 03 November 2017 Degree Bachelor of Business Administration Degree Programme International Business and Logistics Specialisation option International Business and Logistics Instructor(s) Daryl Chapman The thesis is a specialised study about talent management in China to the prevention of brain drain that China has faced for decades. Since China started the economic reform in 1978, there have been more and more Chinese students and academics going abroad to seek for better places and the number of them is in the millions. As the majority of them do never return to China, while the country is suffering from a severe skilled labour shortage, the Chinese government and businesses, both local one and multinationals, have implemented a series of encouraging acts towards overseas Chinese. In 2007, when the Chinese government first launched “the One Thousand Talent Plan”, the difference between how many people leave and how many return has showed a big change towards what Chinese leaders have expected. By applying comprehensive strategies taken from talent management theories, China has welcomed a fresh force of skilled labour in many fields, particularly in science and technology. Beijing launched a plan to reform the Chinese education system, through ways such as popularising education to rural areas, building numerous universities and luring the most prominent experts in the world, methods that are understood as talent development. -

Dissertation JIAN 2016 Final

The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Laada Bilaniuk, Chair Ann Anagnost, Chair Stevan Harrell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology © Copyright 2016 Ge Jian University of Washington Abstract The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Laada Bilaniuk Professor Ann Anagnost Department of Anthropology My dissertation is an ethnographic study of the language politics and practices of college- age English language learners in Xinjiang at the historical juncture of China’s capitalist development. In Xinjiang the international lingua franca English, the national official language Mandarin Chinese, and major Turkic languages such as Uyghur and Kazakh interact and compete for linguistic prestige in different social scenarios. The power relations between the Turkic languages, including the Uyghur language, and Mandarin Chinese is one in which minority languages are surrounded by a dominant state language supported through various institutions such as school and mass media. The much greater symbolic capital that the “legitimate language” Mandarin Chinese carries enables its native speakers to have easier access than the native Turkic speakers to jobs in the labor market. Therefore, many Uyghur parents face the dilemma of choosing between maintaining their cultural and linguistic identity and making their children more socioeconomically mobile. The entry of the global language English and the recent capitalist development in China has led to English education becoming market-oriented and commodified, which has further complicated the linguistic picture in Xinjiang. -

ED054708.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 054 708 HE 002 349 AUTHOR Spencer Richard E.; Awe, Ruth TITLE International Educational Exchange. P. Bibliography. INSTITUTION Institute of International Education, New York N.Y. PUB DATE 70 NOTE 158p- AVAILABLE FROM Institute of Internationa Education, 809 United Nations Plaza, New York, New York 10017 EDRS PRICE MF-S0.65 HC-$6.58 DESC IPTORS *Bibliographies; *Exchange Programs; *Foreign Students; *International Education; International Programs; *Research; Student Exchange Programs; Teacher Exchange Programs ABSTRACT This bibliography was undertaken to facilitate and encourage further research in international education. Sources of the data include library reference works, University Microfilms containing PhD dissertations, US government agencies, foundations and universities. Entries include publications on the International Exchange of Students, Teachers and Specialists and cover: selection, admissions, orientation, scholarships, grants, foreign student advisors, attitudes, and adjustment, hospitality of host country, community relations, academic achievement, returnees, follow-up evaluations, brain drain, professional educators, specialists, US nationals abroad, foreign students and visitors in the US, personnel and program interchanges, immigration policies, international activities of US universities. Entries on.Educational Curriculum cover: English as a second language, linguistics and other languages, courses of study. The last 3 sectional entries are: General Works on International Educational and Cultural Exchange; Cross-Cultural and Psychological Studies Relevant to Educational EX hange; and Bibliographies. (JS) o;c;lopD10-01.0 1 2405-010° w,64.'<cm -10 2B164. 01-0122 1.roz1;x2 .clito ccrupw00 -p 44u2u7LE°- 01-:<-,-.1-01wouuxoctzio 0014.0) 0 MO 'W 0042MOZ WICL,TA° 3 mulwan. 411 :IZI01/1°4 t4. INTERNATIONAL EDUCATIONAL EXCHANGE -4- a)A BIBLIOGRAPHY 4:3 by Richard E. -

The Net Delusion : the Dark Side of Internet Freedom / Evgeny Morozov

2/c pMs (blAcK + 809) soFt-toUcH MAtte lAMinAtion + spot gloss The NeT DelusioN evgeNy Morozov evgeNy The NeT DelusioN PoliTiCs/TeChNology $27.95/$35.50CAN “evgeny Morozov is wonderfully knowledgeable about the internet—he seems “THEREVOLUTIONWILLBETWITTERED!” to have studied every use of it, or every political use, in every country in the declared journalist Andrew sullivan after world (and to have read all the posts). And he is wonderfully sophisticated and protests erupted in iran in June 2009. Yet for tough-minded about politics. this is a rare combination, and it makes for a all the talk about the democratizing power powerful argument against the latest versions of technological romanticism. of the internet, regimes in iran and china His book should be required reading for every political activist who hopes to are as stable and repressive as ever. in fact, AlexAnder KrstevsKi AlexAnder change the world on the internet.” —MiChAel WAlzer, institute for authoritarian governments are effectively Advanced study, Princeton using the internet to suppress free speech, evgeNy Morozov hone their surveillance techniques, dissem- is a contributing editor to Foreign Policy “ evgeny Morozov has produced a rich survey of recent history that reminds us inate cutting-edge propaganda, and pacify and Boston Review and a schwartz Fellow that everybody wants connectivity but also varying degrees of control over their populations with digital entertain- at the new American Foundation. Morozov content, and that connectivity on its own is a very poor predictor of political ment. could the recent Western obsession is currently also a visiting scholar at stan- pluralism.... by doing so, he’s gored any number of sacred cows, but he’s likewise with promoting democracy by digital ford University. -

Review of Pilot

COMING HOME: A STUDY OF VALUES CHANGE AMONG CHINESE POSTGRADUATES AND VISITING SCHOLARS WHO ENCOUNTERED CHRISTIANITY IN THE U.K. ANDREA DEBORAH CLAIRE DICKSON, BA, MIS, MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy JULY 2013 Abstract This thesis examines changes in core values held by postgraduate students and visiting scholars from China who professed belief in Christianity while studying in UK universities. It is the first study to ascertain whether changes remain after return to China. Employing a theoretical framework constructed from work by James Fowler, Charles Taylor, Yuting Wang and Fenggang Yang, it identifies both factors contributing to initial change in the UK and factors contributing to sustained change after return to China. It shows that lasting values change occurred. As a consequence, tensions were experienced at work, socially and in church. However, these were outweighed by benefits, including inner security, particularly after a distressed childhood. Benefits were also experienced in personal relationships and in belonging in a new community, the Church. This was a qualitative, interpretive study employing ethnographic interviews with nineteen people, from eleven British universities, in seven Chinese cities. It was based on the hypotheses that Christian conversion leads to change in values and that evidence for values can be found in responses to major decisions and dilemmas, in saddest and happiest memories and in relationships. Conducted against a backdrop of transnational movement of people and ideas, including a recent increase in mainland Chinese studying abroad which has led to more Chinese in British churches, it contributes new insights into both the contents of sustained Christian conversion amongst Chinese abroad who have since returned to China and factors contributing to it. -

The Heroine's Journey

In the footsteps of the heroine The journey to Integral Feminism Figure 1: ‘Queen of the Night’, © Trustees of the British Museum A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy at the University of Western Sydney 2008 Sarah Nicholson To the women, known and unknown, who have forged the way, and those still to come. Acknowledgements I would like to thank: My first supervisors, Anne Marshall and Susan Murphy, and my co-supervisor Brenda Dobia, for sharing their expertise, critique and inspiration. The Writing and Society group at UWS for their support and assistance, particularly in funding editorial assistance. The School of Social Ecology and the School of Humanities for providing me with Student Project funding to make invaluable contacts, conduct crucial research and attend conferences overseas. The Visiting Scholar scheme of the Centre for Feminist Research, York University, Toronto for hosting me as a visiting postgraduate scholar. The international Integral community – particularly the inspirational Willow Pearson and fellow traveller Vanessa Fisher, for their inspiration, support and encouragement. The Sydney Integral group – particularly Simon Mundy, Tim Mansfield, Vivian Baruch, Helen Titchen-Beeth, and Luke Fullagar - who read and insightfully commented on chapters of this thesis. My parents, Eli, my aunty Joy, my grandparents, and my extended family, for offering me unfailing love, support and assistance. My friends, for supporting me being me, by being you. Rachel Hammond, Martin Robertson, Sarah Roberts, and Sarah Harmelink, Cartia Wollen and Edward Birt, for their assistance with child care in the final stages of this thesis. Particular thanks to Allison Salmon, who is always there when, and indeed before I realise, I need her. -

Fast Company I Mansueto Ventures

To Matt and Kay Farrar, Straus and Giroux 18 West 18th Street, New York 10011 and to Ron Copyright© 2005, 2006, 2007 by Thomas L. Friedman All rights reserved Distributed in Canada by Douglas & Mcintyre Ltd. Printed in the United States of America First edition published in 2005 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux First updated and expanded edition published in 2006 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux First further updated and expanded edition originally published in paperback by Picador in 2007 First further updated and expanded hardcover edition, 2007 Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint excerpts of their work: the Associated Press; Business Monthly; Business Week; City Journal; Discovery Channel/ Discovery Times Channel; Education Week, Editorial Projects in Education; Fast Company I Mansueto Ventures; Forbes; New Perspectives Quarterly; John Seigenthaler; the International Finance Corporation and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development I World Bank; and YaleGlobal Online (http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/). Excerpts from articles from The Washington Post are copyright© 2004. Reprinted with permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Friedman, Thomas L. The world is flat : a brief history of the twenty-first century I Thomas L. Friedman.- 2nd rev. and expanded ed. p. em. Includes index. ISBN-13: 978-0-374-29278-2 (hardcover: alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-374-29278-7 (hardcover: alk. paper) l. Diffusion of innovations. 2. Information society. 3. Globalization Economic aspects. 4. Globalization-Social -

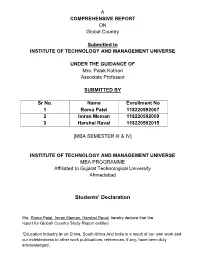

Students' Declaration

A COMPREHENSIVE REPORT ON Global Country Submitted to INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT UNIVERSE UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Mrs. Palak Kothari Associate Professor SUBMITTED BY Sr No. Name Enrollment No 1 Roma Patel 118220592007 2 Imran Meman 118220592009 3 Harshal Raval 118220592015 [MBA SEMESTER III & IV] INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT UNIVERSE MBA PROGRAMME Affiliated to Gujarat Technological University Ahmedabad Students’ Declaration We, Roma Patel, Imran Meman, Harshal Raval, hereby declare that the report for Global/ Country Study Report entitled “Education Industry in on China, South Africa And India is a result of our own work and our indebtedness to other work publications, references, if any, have been duly acknowledged. Place : Vadodara (Signature) Date : ( Name Of Student) Roma Patel Imran Meman Harshal Raval Preface As a MBA student of ITM Universe, Vadodara. Affiliated by GTU. we have made report on Global Country Report on Education sector. So we have selected China , India, South Africa To study the Education sector. We have taken all the topics shown in the report to study the sector. We have learnt a lot from this report about Education In all three countries. The policy and norms of all three country also mentioned in the report. The future challenges also mentioned in the report. We thankful to our head of Department Dr. S. K. Vij to helping us to make report and also to Mrs. Palak Kothari. We the help of our faculty member we made this report. 2 This report will help in future. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT It is our pleasure to place on record my sincere gratitude towards Mrs. -

Anglica. an International Journal of English Studies 2014 23/1

Cena zł 18,00 An International Journal An International Journal 23/1 An of English Studies of English Studies 23/1 Wit Pietrzak Breaking up the language: the struggle with(in) modernity in J. H. Prynne’s Biting the Air Dominika Oramus Two exercises in consilience: Annie Dillard and Kurt Vonnegut on the Galapagos Archipelago as the archetypal Darwinian setting Published since 1988 Joanna Chojnowska “It came up all the time, like a xation ”: the ubiquity of racially-based prejudice as presented in Danzy Senna’s Caucasia Kamil Michta The gardening fallacy: J. M. Coetzee’s Michael K as a parody of Voltaire’s Candide Joanna Jodłowska Aldous Huxley’s early novels: an unfolding dialogue about pain Debbie Lelekis “Pretty maids all in a row”: power and the female child in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden Almas Khan Heart of Darkness: piercing the silence Anna Budziak Parodic and post-classic, British Decadent Aestheticism re-approached Lucyna Krawczyk-Żywko The Strange Case of Mr. Hyde: a Victorian villain and a Victorian detective revisited Małgorzata Łuczyńska-Hołdys “Darkling I listen”: melancholia, self and creativity in Romantic nightingale poems Klaudia Łączyńska From masque to masquerade: monarchy and art in Andrew Marvell’s poems Abhishek Sarkar Thomas Dekker and the spectre of underworld jargon 2014 www.wuw.pl/ksiegarnia logo WUW.indd 1 5/12/2014 12:54:19 PM logo WUW.indd 2 5/12/2014 12:55:07 PM Anglica_OK_ 23-1.indd 1 16.10.2014 11:37 An International Journal of English Studies 23/1 Editor Andrzej Weseliński Associate -

China - Education - Schools - Re-Education - Ann Hulbert - New York Times 04/02/2007 08:37 AM

China - Education - Schools - Re-education - Ann Hulbert - New York Times 04/02/2007 08:37 AM HOME PAGE MY TIMES TODAY'S PAPER VIDEO MOST POPULAR Free 14-Day Trial Welcome, tonysilva0 Member Center Log Out TIMES TOPICS Magazine Magazine All NYT WORLD U.S. N.Y. / REGION BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY SCIENCE HEALTH SPORTS OPINION ARTS STYLE TRAVEL JOBS REAL ESTATE AUTOS THE TIMES MAGAZINE T: STYLE KEY PLAY Re-education Next Article in Magazine (1 of 12) » nytimes.com/sports How good is your bracket? Compare your tournament picks to choices from members of The New York Times sports desk and other players. Also in Sports: The Bracket Blog - all the news leading up to the Final Four Bats Blog: Spring training updates Daniel Traub for The New York Times Play Magazine: How to build a super athlete "Quality Education" Incorporating a Western-style emphasis on extracurriculars, schools like Xiwai International are attracting the children of parents whose own educational ambitions were cut short by the horrors of the Cultural Revolution. By ANN HULBERT Published: April 1, 2007 MOST POPULAR E-MAIL E-MAILED BLOGGED SEARCHED I. The Student PRINT 1. For Girls, It’s Be Yourself, and Be Perfect, Too Enlarge This Image “Definitely wake me up around 9!!! I have an SAVE 2. Ex-Aide Says He’s Lost Faith in Bush important presentation . wake me up at SHARE 3. Poor Nations to Bear Brunt as World Warms that time please. Thanks!! Meijie.” 4. New Bar Codes Can Talk With Your Cellphone The e-mail message, sent to me at 3:55 a.m. -

Suzhi Through Modernization and Development

Seeking suzhi through Modernization and Development By Krista Moramarco Submitted to the graduate degree program in East Asian Languages and Cultures and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Chair: Dr. Megan J. Greene Dr. Keith McMahon Dr. Maggie Childs Date Defended: 8 August, 2017 The thesis committee for Krista Moramarco certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Seeking suzhi through Modernization and Development Chair: Dr. Megan J. Greene Date Approved: September 1, 2017 ii Abstract The Chinese term suzhi is generally translated into English as “quality,” but in fact, the English language does not have a single word that adequately conveys the type of “quality” to which the term suzhi refers. Suzhi refers specifically to the quality of the human, as opposed to the quality of a material, system, or an idea. The evaluation of “human quality” takes into account seemingly countless individual qualities of a person, including one’s physical health and appearance, psychological health, intellect, mannerisms, socio-economic status, and so on. The nuanced criteria under the umbrella of suzhi-evaluation render the term difficult to explain even by the Chinese citizens themselves. This thesis explores the concept of suzhi as it has been presented in government discourse over the course of the last 40 years of reform. Providing a somewhat chronological history of major developmental policies, the thesis illustrates the manner in which top-down policy framing of suzhi imbues it with new meaning in the imaginations of average citizens as they navigate a rapidly modernizing and internationalizing China. -

The Politics of Childhood

one Th e Politics of Childhood Why the low productivity of our country’s enterprise economy and the situation of the inability of our products to compete have not changed in a long time, why agricultural science and technology have not achieved wide dissemination, why precious resources and the ecological environment have not been fully used and protected, why the increase in population has not been eff ectively controlled, and why some bad social conduct cannot be stopped despite repeated bans undoubtedly have many rea- sons, but one important reason is that the suzhi of laborers is low. State Council, People’s Republic of China, “Zhongguo jiaoyu gaige he fazhan gangyao” [An outline for the reform and development of Chinese education], 1993 At the turn of the twenty-first century, some books written by somebody named Huang Quanyu describing school and family life in the United States hit the market in China, making this author a household name in Chinese cities. Titled Education for Quality in America (1999) and Family Education in America (2001), they are fi lled with vignettes describing Huang’s experience of raising a son during his years as a graduate student in the United States, admiringly showcasing American educational practices. Decidedly nontheoretical books aimed at a popular audience, they describe family life, bake sales, and soccer games—mundane middle-class Americana meant to refl ect everything Chinese educators are supposedly doing wrong.1 To illustrate, the fi rst chapter of Education for Quality in America tells a story about how Huang fi rst perceived his son’s art class with disapproval and how he eventually understood the logic behind what had fi rst appeared to be a complete lack of structure and purpose.