Management Plan for Black Bears in Pennsylvania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heraldic Terms

HERALDIC TERMS The following terms, and their definitions, are used in heraldry. Some terms and practices were used in period real-world heraldry only. Some terms and practices are used in modern real-world heraldry only. Other terms and practices are used in SCA heraldry only. Most are used in both real-world and SCA heraldry. All are presented here as an aid to heraldic research and education. A LA CUISSE, A LA QUISE - at the thigh ABAISED, ABAISSÉ, ABASED - a charge or element depicted lower than its normal position ABATEMENTS - marks of disgrace placed on the shield of an offender of the law. There are extreme few records of such being employed, and then only noted in rolls. (As who would display their device if it had an abatement on it?) ABISME - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ABOUTÉ - end to end ABOVE - an ambiguous term which should be avoided in blazon. Generally, two charges one of which is above the other on the field can be blazoned better as "in pale an X and a Y" or "an A and in chief a B". See atop, ensigned. ABYSS - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ACCOLLÉ - (1) two shields side-by-side, sometimes united by their bottom tips overlapping or being connected to each other by their sides; (2) an animal with a crown, collar or other item around its neck; (3) keys, weapons or other implements placed saltirewise behind the shield in a heraldic display. -

Gardening for Native Bees in Utah and Beyond James H

Published by Utah State University Extension and Utah Plant Pest Diagnostic Laboratory ENT-133-09 January 2013 Gardening for Native Bees in Utah and Beyond James H. Cane Linda Kervin Research Entomologist, USDA ARS Logan, UT Pollinating Insect-Biology, Management, Systematics Research Do You Know? • 900 species of native bees reside in Utah. • Some wild bees are superb pollinators of Utah’s tree fruits, raspberries, squashes, melons and cucumbers. • Few of our native bees have much venom or any inclination to sting. • Our native bees use hundreds of varieties of garden flowers, many of them water-wise. • A garden plant need not be native to attract and feed native bees. tah is home to more than 20 percent Uof the 4,000+ named species of wild Fig. 1. Carder bee (Anthidium) foraging at lavender (Lavendula: Lamiaceae).1 bees that are native to North America. Except for bumblebees and some sweat bees, our native bees are solitary, not so- cial, many with just one annual generation that coincides with bloom by their favorite floral hosts. In contrast, the familiar honey- bee is highly social, has perennial colonies, and was brought to North America by settlers from Europe. Regardless of these differences, however, all of our bees need pollen and nectar from flowers. The sugars in sweet nectar power their flight; mother bees also imbibe some nectar to mix with pollen that they gather. Pollen is fortified with proteins, oils and minerals that are es- sential for the diets of their grub-like larvae back at the nest. Our flower gardens can become valuable cafeterias for local populations of diverse native bees. -

Dog, Tracking Dog and Family Dog

FEDERATION CYNOLOGIQUE INTERNATIONALE (AISBL) SECRETARIAT GENERAL: 13, Place Albert 1er B – 6530 Thuin (Belgique) ______________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ 12.07.2002/EN _______________________________________________________________ FCI-Standard N° 84 CHIEN DE SAINT-HUBERT (Bloodhound) 2 TRANSLATION: Mrs Jeans-Brown, revised by Mr R. Pollet and R. Triquet. Official language (FR). ORIGIN: Belgium. DATE OF PUBLICATION OF THE ORIGINAL VALID STANDARD: 13.03.2001. UTILIZATION: Scent hound for large game venery, service dog, tracking dog and family dog. It was and it must always remain a hound which due to its remarkable sense of smell is foremost a leash hound, often used not only to follow the trail of wounded game as in the blood scenting trials but also to seek out missing people in police operations. Due to its functional construction, the Bloodhound is endowed with great endurance and also an exceptional nose which allows it to follow a trail over a long distance and difficult terrain without problems. FCI-CLASSIFICATION: Group 6 Scent hound and related breeds. Section 1 Scent hounds. 1.1 Large sized hounds. With working trial. BRIEF HISTORICAL SUMMARY: Large scent hound and excellent leash hound, with very ancient antecedents. For centuries it has been known and appreciated for its exceptional nose and its great talent for the hunt. It was bred in the Ardennes by the monks of the Abbaye de Saint-Hubert. It is presumed to descend from black or black and tan hounds hunting in packs which were used in the 7th century by the monk Hubert, who was later made a bishop and who when canonised became the patron saint of hunters. -

2. Hound Hunting Is Virtually the Only Form of Non-Consumptive Hunting, and Is Very Similar to Catch-And-Release Fishing

What’s Right About Hunting With Hounds: By Josh Brones, President of California Houndsmen for Conservation Senate Bill 1221 would ban the use of hounds to hunt bobcats and bears in California. The sponsors of SB 1221 allege that the use of hounds is inhumane, unsporting and unfair. Unfortunately, the information they use to support this bill comes from anti-hunting organizations that have no motivation to be truthful about the practice. I have raised, trained, and hunted with hounds since 1986, and I believe it is critically important for legislators, the media, and the public to hear from people who actually hunt with hounds in order to truly understand and appreciate the many aspects of this time-honored tradition. Here are 10 facts about hound hunting: 1. Hound hunting has been legal since the inception of the California Department of Fish and Game, and is relied upon to help meet management goals. The Department’s own environmental impact documents consistently indicate that the use of dogs and radio telemetry collars does not threaten the survival or prosperity of our bear population. In fact, California’s bear population has nearly quadrupled over the past thirty years...all while the use of hounds has been permitted. 2. Hound hunting is virtually the only form of non-consumptive hunting, and is very similar to catch-and-release fishing. The ultimate goal of using hounds is not the harvest of wildlife, but the enjoyment gained in training, listening to, and interacting with the dogs during the pursuit. As such, hound hunters often take fewer animals than is prescribed by the Department on an annual basis. -

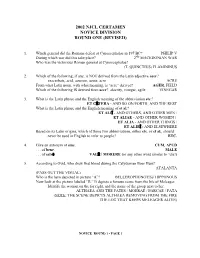

2002 Njcl Certamen Novice Division Round One (Revised)

2002 NJCL CERTAMEN NOVICE DIVISION ROUND ONE (REVISED) 1. Which general did the Romans defeat at Cynoscephalae in 197 BC? PHILIP V During which war did this take place? 2ND MACEDONIAN WAR Who was the victorious Roman general at Cynoscephalae? (T. QUINCTIUS) FLAMININUS 2. Which of the following, if any, is NOT derived from the Latin adjective acer? exacerbate, acid, acumen, acute, acre ACRE From what Latin noun, with what meaning, is “acre” derived? AGER, FIELD Which of the following IS derived from acer? alacrity, vinegar, agile VINEGAR 3. What is the Latin phrase and the English meaning of the abbreviation etc.? ET CTERA - AND SO ON/FORTH, AND THE REST What is the Latin phrase and the English meaning of et al.? ET ALI¦ - AND OTHERS, AND OTHER MEN / ET ALIAE - AND OTHER WOMEN / ET ALIA - AND OTHER THINGS / ET ALIB¦ - AND ELSEWHERE Based on its Latin origins, which of those two abbreviations, either etc. or et al., should never be used in English to refer to people? ETC. 4. Give an antonym of sine. CUM, APUD . of bene. MALE . of salv‘. VAL / MORERE (or any other word similar to “die!) 5. According to Ovid, who drew first blood during the Calydonian Boar Hunt? ATALANTA (PASS OUT THE VISUAL) Who is the hero depicted in picture “A”? BELLEROPHON(TES)/ HIPPONOUS Now look at the picture labeled “B.” It depicts a famous scene from the life of Meleager. Identify the woman on the far right, and the name of the group next to her. ALTHAEA AND THE FATES / MOERAE / PARCAE / FATA (NOTE: THE SCENE DEPICTS ALTHAEA REMOVING FROM THE FIRE THE LOG THAT KEEPS MELEAGER ALIVE) NOVICE ROUND 1 - PAGE 1 6. -

Domestic Dog Breeding Has Been Practiced for Centuries Across the a History of Dog Breeding Entire Globe

ANCESTRY GREY WOLF TAYMYR WOLF OF THE DOMESTIC DOG: Domestic dog breeding has been practiced for centuries across the A history of dog breeding entire globe. Ancestor wolves, primarily the Grey Wolf and Taymyr Wolf, evolved, migrated, and bred into local breeds specific to areas from ancient wolves to of certain countries. Local breeds, differentiated by the process of evolution an migration with little human intervention, bred into basal present pedigrees breeds. Humans then began to focus these breeds into specified BREED Basal breed, no further breeding Relation by selective Relation by selective BREED Basal breed, additional breeding pedigrees, and over time, became the modern breeds you see Direct Relation breeding breeding through BREED Alive migration BREED Subsequent breed, no further breeding Additional Relation BREED Extinct Relation by Migration BREED Subsequent breed, additional breeding around the world today. This ancestral tree charts the structure from wolf to modern breeds showing overlapping connections between Asia Australia Africa Eurasia Europe North America Central/ South Source: www.pbs.org America evolution, wolf migration, and peoples’ migration. WOLVES & CANIDS ANCIENT BREEDS BASAL BREEDS MODERN BREEDS Predate history 3000-1000 BC 1-1900 AD 1901-PRESENT S G O D N A I L A R T S U A L KELPIE Source: sciencemag.org A C Many iterations of dingo-type dogs have been found in the aborigine cave paintings of Australia. However, many O of the uniquely Australian breeds were created by the L migration of European dogs by way of their owners. STUMPY TAIL CATTLE DOG Because of this, many Australian dogs are more closely related to European breeds than any original Australian breeds. -

Peeps at Heraldry Agents America

"gx |[iitrt$ ^tul\xtff SHOP CORKER BOOK |— MfNUE H ,01 FOURTH ».u 1 N. Y. ^M ^.5 ]\^lNicCi\ /^OAHilf'ii ^it»V%.^>l^C^^ 5^, -^M - 2/ (<) So THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA GIFT OF William F. Freehoff, Jr. PEEPS AT HERALDRY AGENTS AMERICA .... THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 64 & 66 FIFTH Avenue, NEW YORK ACSTRAiAETA . OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 205 FLINDERS Lane, MELBOURNE CANADA ...... THE MACMILLAN COMPANY OF CANADA, LTD. St. MARTIN'S HOUSE, 70 BOND STREET. TORONTO I^TDIA MACMILLAN & COMPANY. LTD. MACMILLAN BUILDING, BOMBAY 309 Bow Bazaar Street, CALCUTTA PLATE 1. HEKALU. SHOWING TABARD ORIGINALLY WORN OVKR MAIL ARMOUR. PEEPS AT HERALDRY BY PHGEBE ALLEN CONTAINING 8 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOUR AND NUMEROUS LINE DRAWINGS IN THE TEXT GIFT TO MY COUSIN ELIZABETH MAUD ALEXANDER 810 CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. AN INTRODUCTORY TALK ABOUT HERALDRY - I II. THE SHIELD ITS FORM, POINTS, AND TINCTURES - 8 III. DIVISIONS OF THE SHIELD - - - - l6 IV. THE BLAZONING OF ARMORIAL BEARINGS - -24 V. COMMON OR MISCELLANEOUS CHARGES - " 3^ VI. ANIMAL CHARGES - - - - "39 VII. ANIMAL CHARGES (CONTINUED) - - "47 VIII. ANIMAL CHARGES (CONTINUED) - - " 5^ IX. INANIMATE OBJECTS AS CHARGES - - - ^3 X. QUARTERING AND MARSHALLING - - "70 XI. FIVE COATS OF ARMS - - - "74 XII. PENNONS, BANNERS, AND STANDARDS - - 80 VI LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS PLATE 1. Herald showing Tabard, originally Worn over Mail Armour - - - - - frontispiece FACING PAGE 2. The Duke of Leinster - - - - 8 Arms : Arg. saltire gu. Crest : Monkey statant ppr., environed round the loins and chained or. Supporters : Two monkeys environed and chained or. Motto : Crom a boo. - - 3. Marquis of Hertford - - - 16 Arms : Quarterly, ist and 4th, or on a pile gu., between 6 fleurs-de- lys az,, 3 lions passant guardant in pale or ; 2nd and 3rd gu., 2 wings conjoined in lure or. -

I Am Eagle” – Depictions of Raptors and Their Meaning in the Art of Late Iron Age and Viking Age Scandinavia (C

“I am Eagle” – Depictions of raptors and their meaning in the art of Late Iron Age and Viking Age Scandinavia (c. AD 400–1100) By Sigmund Oehrl Keywords: Raptor and fish, picture stones, Old Norse Poetry, Vendel Period, Viking Period Abstract: This paper is restricted to some of the most frequent and most relevant raptor motifs in the iconography of Late Iron Age and Viking Scandinavia, focussing on some of the most prominent materials. Raptors are an important motif in Scandinavian, Anglo-Saxon and Continental Germanic art, carrying very different meanings. In the Migration Period, the raptor-fish motif seems to be con- nected with ideas of regeneration – probably influenced by ancient and Christian traditions. It occurs on precious artefacts like the Golden Horns from Gallehus and a gold bracteate (pendant) from the British Museum. In the iconography of the gold bracteates, birds of prey are a common motif and are closely linked to the chief god, Odin. During the Vendel/Merovingian and Viking Periods, on decorated helmets and picture stones in particular, the eagle was associated with fighting, war and death, as in Old Norse skaldic poetry. In Late Viking art, especially on rune stones, the topic of falconry was gaining in importance. Hunting with raptors seems also to be reflected in the use of raptor motifs in Viking heraldry (Rurikid dynasty), which refer to falconry as a particularly noble form of hunting and an explicitly aristocratic pastime. IntroductIon Birds of prey have been omnipresent in the art of Late Iron Age and Viking Scandinavia since the Migration Period, when Germanic styles and iconography – mainly inspired by Late Roman art – became increasingly independent and started to establish themselves in large parts of central and northern Europe. -

The Clark Family History” by Linda Benson Cox, 2003; Edited, 2006 “Take Everything with a Grain of Salt”

“The Clark Family History” By Linda Benson Cox, 2003; Edited, 2006 “Take everything with a grain of salt” Old abandoned farmhouse, 2004 View of the Tennessee River Valley looking toward Clifton, 2004 "Let us go to Tennessee. We come, you and I, for the music and the mountains, the rivers and the cotton fields, the corporate towers and the country stores. We come for the greenest greens and the haziest blues and the muddiest browns on earth. We come for the hunters and storytellers, for the builders and worshippers. We come for dusty roads and turreted cities, for the smells of sweet potato pie and sweat of horses and men. We come for our quirkiness and our cleverness. We come to celebrate our common 1 bonds and our family differences." REVEREND WILLIAM C. CLARK While Tennessee was still a territory, trappers and scouts were searching for prospective home sites in West Tennessee including the area where Sardis now stands. Soon families followed these scouts over the mountains of East Tennessee into Middle Tennessee. Some remained in Middle Tennessee, but others came on into West Tennessee in a short time. Thus, some settled in Sardis and the surrounding area...the roads were little more than blazed paths…as did other early settlers, the first settlers of Sardis settled near a spring…as early as 1825, people from miles around came to this “Big Meeting” place just as others were gathering at other such places during that time of great religious fervor. It was Methodist in belief, but all denominations were made welcome…as a result of the camp meetings people began to come here and establish homes. -

Clan Drummond

CLAN DRUMMOND ARMS Or, three bars wavy Gules CREST On a crest coronet Or, a goshawk, wings displayed Proper, armed and belled Or, jessed Glues MOTTO Virtutem coronat honos (Honor crowns virtue) On Compartment Gang warily SUPPORTERS (on a compartment é of caltrops Proper) Two savages wreathed about the head and middle with oak-leaves all Proper, each carrying a baton Sable on his exterior shoulder STANDARD Azure. A St Andrew’s Cross Argent in the hoist and of two tracts Or and Gules semée of caltops Argent, upon which is depicted the rest in the first compartment, the sleuthhound Badge in the second compartment, and a holly leaf Proper in the third compartment, along with the Motto ‘Gang warily’ in letters Or upon two transverse bands wavy Sable PINSEL Gules, bearing upon a Crest coronet of four (three visible) strawberry leaves Or the above Crest within a strap of cuir brunatre buckled and embellished Or, inscribed with this Motto ‘Virtutem coronat honos’ in letters of the Field, all within a circlet also Or, bearing this title ‘An Drumenach Mor’ in letters also of the Field, the same ensigned with an Earl’s coronet, and in an Escrol Or surmounting a leaf of holly Proper this slogan ‘Gang warily’ in letters of the field BADGES 1. A sleuth-hound passant Argent, collared and leashed Gules, (the leash shown refluxed over its back) 2. A caltrop Argent PLANT BADGE Holly One of the families residing on the edge of the Highlands, the Drummonds have always played a prominent part in Scottish affairs. -

Border Collie

SCRAPS Breed Profile BLOODHOUND Stats Country of Origin: Belgium Group: Hound Use today: Companion and tracker. Life Span: 10 to 12 years Color: Colors include black & tan, liver & tan, red & tawny and red. Sometimes there is a small amount of white on the chest, feet and tip of the stern. Coat: The coat is wrinkled, short and fairly hard in texture, with softer hair on the ears and skull. Grooming: The smooth, shorthaired coat is easy to groom. Groom with a hound glove, and bathe only when necessary. A rub with a rough towel or chamois will leave the coat gleaming. Clean the long, floppy ears regularly. Bloodhounds have a distinctive dog-type odor. This breed is an average shedder. Height: Males 25 – 27 inches; Females 23 - 25 inches Weight: Males 90 - 110 pounds; Females 80 - 100 pounds Profile In Brief: While Bloodhounds are extremely on the ears and skull. Colors include black & affectionate, they are take-charge dogs, so it is tan, liver & tan, red & tawny and red. Sometimes important to be kind, but be the undisputed boss there is a small amount of white on the chest, in your household. Bloodhounds should be feet and tip of the stern. groomed weekly to eliminate dead hair and facilitate a routine that will help them look, feel, Temperament: The Bloodhound is a kind, and smell better. Although affectionate, they can patient, noble, mild-mannered and lovable dog. possess shy natures, sensitive to kindness or Gentle, affectionate and excellent with children, correction by their master. this is truly a good natured companion. -

Downloaded on 2017-02-12T08:16:26Z

Title Redefining military memorials and commemoration and how they have changed since the 19th century with a focus on Anglo-American practice Author(s) Levesque, J. M. André Publication date 2013 Original citation Levesque, J. M. A. 2013. Redefining military memorials and commemoration and how they have changed since the 19th century with a focus on Anglo-American practice. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Link to publisher's http://library.ucc.ie/record=b2095603 version Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2013, J. M. André Levesque. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Embargo information No embargo required Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/1677 from Downloaded on 2017-02-12T08:16:26Z REDEFINING MILITARY MEMORIALS AND COMMEMORATION AND HOW THEY HAVE TH CHANGED SINCE THE 19 CENTURY WITH A FOCUS ON ANGLO-AMERICAN PRACTICE Thesis presented for the degree of Ph.D. by Joseph Marc André Levesque, M.A. Completed under the supervision of Dr. Michael B. Cosgrave, School of History, National University of Ireland, Cork Head of School of History – Professor Geoffrey Roberts September 2013 1 2 ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 9 CHAPTER 1 - LITERATURE REVIEW ........................................................ 15 Concepts and Sites of Collective