Downloaded on 2017-02-12T08:16:26Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

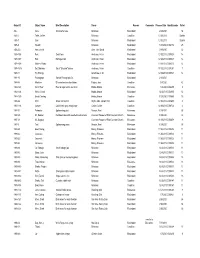

D4 DEACCESSION LIST 2019-2020 FINAL for HLC Merged.Xlsx

Object ID Object Name Brief Description Donor Reason Comments Process Date Box Barcode Pallet 496 Vase Ornamental vase Unknown Redundant 2/20/2020 54 1975-7 Table, Coffee Unknown Condition 12/12/2019 Stables 1976-7 Saw Unknown Redundant 12/12/2019 Stables 1976-9 Wrench Unknown Redundant 1/28/2020 C002172 25 1978-5-3 Fan, Electric Baer, John David Redundant 2/19/2020 52 1978-10-5 Fork Small form Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-7 Fork Barbeque fork Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-9 Masher, Potato Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-16 Set, Dishware Set of "Bluebird" dishes Anderson, Helen Condition 11/12/2019 C001351 7 1978-11 Pin, Rolling Grantham, C. W. Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1981-10 Phonograph Sonora Phonograph Co. Unknown Redundant 2/11/2020 1984-4-6 Medicine Dr's wooden box of antidotes Fugina, Jean Condition 2/4/2020 42 1984-12-3 Sack, Flour Flour & sugar sacks, not local Hobbs, Marian Relevance 1/2/2020 C002250 9 1984-12-8 Writer, Check Hobbs, Marian Redundant 12/3/2019 C002995 12 1984-12-9 Book, Coloring Hobbs, Marian Condition 1/23/2020 C001050 15 1985-6-2 Shirt Arrow men's shirt Wythe, Mrs. Joseph Hills Condition 12/18/2019 C003605 4 1985-11-6 Jumper Calvin Klein gray wool jumper Castro, Carrie Condition 12/18/2019 C001724 4 1987-3-2 Perimeter Opthamology tool Benson, Neal Relevance 1/29/2020 36 1987-4-5 Kit, Medical Cardboard box with assorted medical tools Covenant Women of First Covenant Church Relevance 1/29/2020 32 1987-4-8 Kit, Surgical Covenant -

LTN Winter 2021 Newsletter

THE LUTYENS TRUST To protect and promote the spirit and substance of the work of Sir Edwin Lutyens O.M. NEWSLETTER WINTER 2021 A REVIEW OF NEW BOOK ARTS & CRAFTS CHURCHES BY ALEC HAMILTON By Ashley Courtney It’s hard to believe this is the first book devoted to Arts and Crafts churches in the UK, but then perhaps a definition of these isn’t easy, making them hard to categorise? Alec Hamilton’s book, published by Lund Humphries – whose cover features a glorious image of St Andrew’s Church in Sunderland, of 1905 to 1907, designed by Albert Randall Wells and Edward Schroeder Prior – is split into two parts. The first, comprising an introduction and three chapters, attempts a definition, placing this genre in its architectural, social and religious contexts, circa 1900. The second, larger section divides the UK into 14 regions, and shows the best examples in each one; it also includes useful vignettes on artists and architects of importance. For the author, there is no hard- and-fast definition of an Arts and Crafts church, but he makes several attempts, including one that states: “It has to be built in or after 1884, the founding date of the Art Workers’ Guild”. He does get into a bit of a pickle, however, but bear with it as there is much to learn. For example, I did not know about the splintering of established religion, the Church of England, into a multitude of Nonconformist explorations. Added to that were the social missions whose goal was to improve the lot of the impoverished; here social space and church overlapped and adherents of the missions, such as CR Ashbee, taught Arts and Crafts skills. -

Do You Know Where This

The SAR Colorguardsman National Society, Sons of the American Revolution Vol. 6 No. 3 Oct 2017 Inside This Issue From the Commander From the Vice-Commander Ad Hoc Committee Update Do you Firelock Drill positions Color Guard Commanders SAR Vigil at Mt Vernon know where Reports from the Field - 13 Societies Congress Color Guard Breakfast this is? Change of Command Ring Ritual Color Guardsman of the Year National Historic Sites Calendar Color Guard Events 2017 The SAR Colorguardsman Page 2 The purpose of this Commander’s Report Magazine is to It has been a very active two month period since the Knoxville Congress in provide July. I have had the honor of commanding the Color Guard at the Installation interesting Banquet in Knoxville, at the Commemoration of the Battle of Blue Licks in articles about the Kentucky, at the Fall Leadership Meeting in Louisville,the grave markings of Revolutionary War and Joshua Jones and George Vest, and at the Anniversary of the Battle of Kings Mountain in South Carolina. information regarding the I have also approved 11 medals - 6 Molly Pitcher Medals and 5 Silver Color activities of your chapter Guard Medals. Please review the Color Guard Handbook for the qualifica- tions for these medals as well as the National Von Steuben Medal for Sus- and/or state color guards tained Activity. The application forms for these can be found on the National website. THE SAR The following goals have been established for the National Color Guard COLORGUARDSMAN for 2017 to 2018: The SAR Colorguardsman is 1) Establish published safety protocols and procedures with respect to Color Guard conduct published four times a year and use of weaponry at events. -

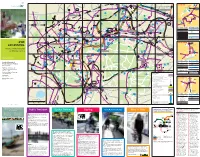

Bus Routes Running Every Day (Black Numbers)

Richmond Bus & Cycle M&G 26/01/2011 15:32 Page 1 2011 ABCDEFGH . E S E A to Heston Y A L Kew Bridge U O L OAD to W N I N N R KEW N Steam G O K BRENTFORD E RICHMOND R O L Ealing 267 V T G I A Museum BRIDGE E 391 Queen T N Y O U N A S A Orange Tree D R T Charlotte S A G S D O . E R 391 P U U O R T E Theatre D S C H R IN B O W H Hall/R.A.C.C. G 267 IS PAR H OAD R L W A . R L G 65 DE N A G K RO SYON LANE E IC T OLDHAW A Parkshot N E V R S GUNNERSBURY K CHISWICK D W O E D 267 T M D . N R E T Y 111 R O 65 BRIDGE ROAD BATH ROAD B P O . KEW K A H E PARK K GOLDHAWK ROAD W AT D T R D O H E M I W D H A W G R 267 E E H A L A A D LE G L R S H O R L 267 T R T D EY Little E I O O RE D R U HIGH ST ROAD N A Waterman’s R RO 391 TURNHAM L A H37.110 A D P B Green N A O S D Library R D Arts Centre G O GREEN D RICHMOND T H22 281 H37 OAD Kew Green W R E STAMFORD A G School K Richmond C U N STATION I ‘Bell’ Bus Station D DON 65 BROOK Richmond Q L A LON Green L R O B D E U N Theatre E 1 391 S CE A H RAVENSCOURT 1 E H D T E H to Hatton Cross and W LONDON D Main W A O R T HIGH STREET Thornbury A RS R R G S Kew Palace O Falcons PARK Heathrow Airport ISLEWORTH O Gate D O R O to F B Playing T R O D N E H37 A A ROAD H22 . -

A Brief History of War Memorial Design

A BRIEF HISTORY OF WAR MEMORIAL DESIGN War Memorials in Manitoba: An Artistic Legacy A BRIEF HISTORY OF WAR MEMORIAL DESIGN war memorial may take many forms, though for most people the first thing that comes to mind is probably a freestanding monument, whether more sculptural (such as a human figure) or architectural (such as an arch or obelisk). AOther likely possibilities include buildings (functional—such as a community hall or even a hockey rink—or symbolic), institutions (such as a hospital or endowed nursing position), fountains or gardens. Today, in the 21st century West, we usually think of a war memorial as intended primarily to commemorate the sacrifice and memorialize the names of individuals who went to war (most often as combatants, but also as medical or other personnel), and particularly those who were injured or killed. We generally expect these memorials to include a list or lists of names, and the conflicts in which those remembered were involved—perhaps even individual battle sites. This is a comparatively modern phenomenon, however; the ancestors of this type of memorial were designed most often to celebrate a victory, and made no mention of individual sacrifice. Particularly recent is the notion that the names of the rank and file, and not just officers, should be set down for remembrance. A Brief History of War Memorial Design 1 War Memorials in Manitoba: An Artistic Legacy Ancient Precedents The war memorials familiar at first hand to Canadians are most likely those erected in the years after the end of the First World War. Their most well‐known distant ancestors came from ancient Rome, and many (though by no means all) 20th‐century monuments derive their basic forms from those of the ancient world. -

Ecclesiasticus, War Graves, and the Secularization of British Values It Is

Ecclesiasticus, War Graves, and the secularization of British Values Item Type Article Authors Vincent, Alana M. Citation Vincent, A. (2018). Ecclesiasticus, War Graves, and the secularization of British Values. Journal of the Bible and its Reception, 4(2). DOI 10.1515/jbr-2017-0014 Publisher De Gruyter Journal Journal of the Bible and its Reception Download date 30/09/2021 14:30:42 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/620672 Ecclesiasticus, War Graves, and the secularization of British Values It is curiously difficult to articulate exactly what alterations in memorial practices occurred as a result of the First World War. Battlefield burials have a long established, though not uncontroversial, history, as does the practice of the state assuming familial guardianship over the remains of deceased soldiers;1 the first village memorials to soldiers who never returned from fighting overseas appear in Scotland after the Crimean war;2 the first modern use of lists of names in a memorial dates to the French Revolution.3 We see an increase in memorial practices that were previously rare, but very little wholesale invention.4 1 See discussion in Alana Vincent, Making Memory: Jewish and Christian Explorations in Monument, Narrative, and Liturgy (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2013), especially ch. 2, 32–44. 2 Monument located near Balmaclellan Parish Church. See “Balmaclellan Crimean War,” Imperial War Museums, accessed 27 July 2017, http://www.iwm.org.uk/memorials/item/memorial/44345 3 See Joseph Clark, Commemorating the Dead in Revolutionary France: Revolution and Remembrance, 1789-1799 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007). -

ANNOUNCEMENTS by the MAYOR 1. on 5Th July 2012, I Was Delighted

ANNOUNCEMENTS BY THE MAYOR th 1. On 5 July 2012, I was delighted to attend Ealing Hammersmith & West London College, LLDD Awards Ceremony, Colet Gardens, W14 th 2. On 5 July, I attended the Standing Together event, Small Hall, HTH, W6 th 3. On 5 July, I was delighted to host and present with Cllr Greg Smith, HM The Queen’s (1952-2012) Diamond Jubilee Medals to members of staff from Parks Constabulary H&F, Mayor’s Parlour, HTH W6 th 4. On 5 July, accompanied by my consort, I attended The Regimental Cocktail Party, The Guards Museum, Wellington Barracks, Birdcage Walk SW1 th 5. On 6 July, I attended the Kumon Education Award Ceremony, W12 th 6. On 6 July, I attended the Mayor of Ealing’s Charity event, Ealing Town Hall, W5 th 7. On 7 July, accompanied by Cllr Frances Stainton, Deputy Mayor, I attended and officially opened ‘Fair on the Green’, Parsons Green, SW6 th 8. On 7 July, I attended All Saints School event, Bishops Park, SW6 th 9. On 7 July, I attended the National Childbirth Trust and Putney Branch Charity Fun Walk, FFC, SW6 th 10. On 7 July, I attended Addison Primary School event, W14 th 11. On 8 July, I attended the ‘Paggs Cup’ Football Tournament, South Park, SW6 th st 12. On 9 July, I attended the 21 Fulham Brownies charity cake sale in aid of Dementia UK, St Dionis Church Hall, St Dionis Road, SW6 th 13. On 9 July, I attended and spoke at the Business Awards, Basra Restaurant, W6 th 14. -

John T. Adams

John T. Adams John T. Adams, 84, of Cross Plains TX, passed away Tuesday 5/3/11 at home with his wife and sister with him. He was born in Midland, TX on 4/6/27 to John Elkins Adams and Elna Enyart Adams. They moved to Colorado City shortly after his birth, where he spent his childhood and teen years, graduating from Colorado High School in 1944. Johnny, as he was known to family and friends, eagerly joined the Navy immediately upon graduation, and served in the Pacific theater, mainly on the island of Guam. At the war’s end, he returned to Colorado City, and worked for the Post Office, and shortly thereafter became engaged to his lifelong love, Bettye Sue Vaught. They were married on 12/24/47, and embarked on a remarkable 63 year journey together. He went to work for Shell Pipe Line Corp. as a pipeliner in 1950, in Wink, TX. He and Bettye Sue drove into town in a brand new Ford Crestliner that remains in the family to this day. Their career with Shell took them to several locales, in West Texas and South Louisiana, offering the opportunity to experience varied cultures and lifestyles. He retired from Shell in 1984, as District Superintendant, in Midland, TX. In 1953, after the birth of their first son, Tommy, they purchased acreage in Callahan Co., near Cross Plains, TX. In partnership with his sister Elizabeth and her husband Pat Shield. They farmed, ran cows on the place, and fell in love with the area, their neighbors, and people of Cross Plains. -

Heraldic Terms

HERALDIC TERMS The following terms, and their definitions, are used in heraldry. Some terms and practices were used in period real-world heraldry only. Some terms and practices are used in modern real-world heraldry only. Other terms and practices are used in SCA heraldry only. Most are used in both real-world and SCA heraldry. All are presented here as an aid to heraldic research and education. A LA CUISSE, A LA QUISE - at the thigh ABAISED, ABAISSÉ, ABASED - a charge or element depicted lower than its normal position ABATEMENTS - marks of disgrace placed on the shield of an offender of the law. There are extreme few records of such being employed, and then only noted in rolls. (As who would display their device if it had an abatement on it?) ABISME - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ABOUTÉ - end to end ABOVE - an ambiguous term which should be avoided in blazon. Generally, two charges one of which is above the other on the field can be blazoned better as "in pale an X and a Y" or "an A and in chief a B". See atop, ensigned. ABYSS - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ACCOLLÉ - (1) two shields side-by-side, sometimes united by their bottom tips overlapping or being connected to each other by their sides; (2) an animal with a crown, collar or other item around its neck; (3) keys, weapons or other implements placed saltirewise behind the shield in a heraldic display. -

Guidebook: American Revolution

Guidebook: American Revolution UPPER HUDSON Bennington Battlefield State Historic Site http://nysparks.state.ny.us/sites/info.asp?siteId=3 5181 Route 67 Hoosick Falls, NY 12090 Hours: May-Labor Day, daily 10 AM-7 PM Labor Day-Veterans Day weekends only, 10 AM-7 PM Memorial Day- Columbus Day, 1-4 p.m on Wednesday, Friday and Saturday Phone: (518) 279-1155 (Special Collections of Bailey/Howe Library at Uni Historical Description: Bennington Battlefield State Historic Site is the location of a Revolutionary War battle between the British forces of Colonel Friedrich Baum and Lieutenant Colonel Henrick von Breymann—800 Brunswickers, Canadians, Tories, British regulars, and Native Americans--against American militiamen from Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire under Brigadier General John Stark (1,500 men) and Colonel Seth Warner (330 men). This battle was fought on August 16, 1777, in a British effort to capture American storehouses in Bennington to restock their depleting provisions. Baum had entrenched his men at the bridge across the Walloomsac River, Dragoon Redoubt, and Tory Fort, which Stark successfully attacked. Colonel Warner's Vermont militia arrived in time to assist Stark's reconstituted force in repelling Breymann's relief column of some 600 men. The British forces had underestimated the strength of their enemy and failed to get the supplies they had sought, weakening General John Burgoyne's army at Saratoga. Baum and over 200 men died and 700 men surrendered. The Americans lost 30 killed and forty wounded The Site: Hessian Hill offers picturesque views and interpretative signs about the battle. Directions: Take Route 7 east to Route 22, then take Route 22 north to Route 67. -

Remembrance Weekend 11-12/11/2016

Remembmbrance Days Deutscher Soldatenfriedhof Langemark vrijdag 11 & zaterdag 12 november 2016 Remembrance Days 2016 Vrijdag 11 & zaterdag 12 november 2016 Voor het elfde jaar op rij kunnen wij in Ieper de plechtigheden bijwonen naar aanleiding van de herdenking van de Wapenstilstand. Dankzij het stadsbestuur van Ieper en dankzij het bestuur van de Last Post Association kunnen wij ook dit jaar de speciale Last Post plechtigheid op 11 november om 11 uur onder de Menenpoort bijwonen. Naast het traditionele programma dat afgesloten wordt met het concert The Great War Remembered in de Sint-Maarten kathedraal worden dit jaar twee extra activiteiten aan het programma toegevoegd. In de namiddag volgen we een workshop in de Ieperse kazematten van Coming World Remember Me. Dit project wordt uitgevoerd in opdracht van de provincie West-Vlaanderen en maakt deel uit van het grootschalige herinneringsproject GoneWest/Reflections on the Great War. Tijdens de periode 2014-2018 nemen duizenden mensen uit Vlaanderen maar ook uit de rest van de wereld, deel aan de making of door 600.000 beeldjes uit klei te boetseren. Daarbij staat elk beeldje voor één van de 600.000 slachtoffers die in België het leven lieten tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog. Bij elk beeldje hoort een dogtag, een identificatieplaatje voor frontsoldaten. Op deze dog tag staat een slachtoffernaam uit de digitale ‘Namenlijst’ die door het In Flanders Fields Museum in Ieper wordt samengesteld. Ook de naam van de maker komt op de dog tag. Zo verenigen verschillende nationaliteiten en generaties zich in de herdenking. In het voorjaar van 2018 zal de installatie geïmplementeerd worden op één van de meest bevochten plekken van de Eerste Wereldoorlog: het niemandsland van de frontzone rond Ieper. -

Walker Percy, Looking for the Right Happened in the Trevon Martin Hate Crime

2013 Presented By The Pirate’s Alley Faulkner Society Photograph by Joséphine Sacabo Faith & The Search for Meaning As Inspiration for The Arts Published December 1, 2013, New Orleans, LA Guarantors Bertie Deming Smith & The Deming Foundation, Cathy Pierson & Charles Heiner Theodosia Nolan, Tia & James Roddy & Peter Tattersall Judith “Jude” Swenson In Memory of James Swenson Randy Fertel and the Ruth U. Fertel Foundation Joseph DeSalvo, Jr., Rosemary James & Faulkner House, Inc. Frank G. DeSalvo, Attorney The J.J. and Dr. Donald Dooley Fund: Samuel L. Steel, III, Administrator Pam Friedler Joséphine Sacabo & Dalt Wonk Louisiana Division of the Arts, Department of Culture, Recreation & Tourism The State Library of Louisiana & The Louisiana Festival of the Book The Louisiana State Museum Hotel Monteleone & The Monteleone Family: Anne Burr, Greer & David Monteleone, Denise Monteleone, Ruthie Monteleone Anne & Ron Pincus Diane Manning, Floyd McLamb, Courtenay McDowell & Richard Gregory Hartwig & Nancy Moss In Memory of Betty Moss, New Orleans Hispanic Heritage Foundation David Speights in Memory of Marti Speights Mary Freeman Wisdom Foundation, Joyce & Steve Wood Zemurray Foundation Good Friends Jennifer E. Adams; Barbara Arras; Barbara & Edwin Beckman; Deena Bedigian; John & Marcia Biguenet; C.J. Blanda; Roy Blount, Jr. & Joan Griswold; Angie Bowlin; Birchey Butler; Charles Butt; Hortensia Calvo; Batou & Patricia Chandler Cherie Chooljian; Jackie Clarkson; Ned Condini; Mary Len Costa; Moira Crone & Rodger Kamenetz; Jerri Cullinan & Juli Miller Hart; W. Brent Day; Susan de la Houssaye; Stephanie, Robin, & Joan Durant; Louis Edwards; James Farwell & Gay Lebreton;Madeline Fischer; Christopher Franzen, Patty Friedmann; Jon Geggenheimer; David & Sandra Groome; Douglas & Elaine Grundmeyer; Christine Guillory; Janet & Steve Haedicke; Michael Harold & Quinn Peeper; Ken Harper & David Evard; W.