Levelling up Local Government in England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mark Cathcart, Planning Officer By

Rother District Council Town Hall London Road TN39 3JX Attn: Planning Committee Members cc: Mark Cathcart, Planning Officer By email only Your ref: RR/2019/1659/P Our ref: (MOO2/1)-MM/AP Email: 7 August 2020 FOR PLANNING COMMITTEE MEETING ON 13 AUGUST 2020 Re: PGL, Former Pestalozzi Site, Sedlescombe; Application No. RR/2019/1659/P Dear Planning Committee Members, We act for a group of 17 local residents opposed to the above application. There are multiple reasons why we consider that permission for this application should be refused. We have today sent a de- tailed legal letter to the Planning Officer setting out a number of these, which is enclosed (Appendix 1). We are writing here to set out a brief summary of these points, which we hope may assist your consideration of the application: The Fallback Position • The Officer’s Report (“OR”) significantly underestimates the additional floor area that the proposed development represents when compared with the existing permission. (para. 7.4.2) At a minimum, the increase would be 1,217 sqm (50% more than what is said in the OR, excluding the permanent concrete-based ‘tented area’, which would add approximately another 1,050 sqm). This is due to the fact that the OR fails to recognize that Swiss Hall would have to be demolished if the other accommodation onsite were constructed, as this was an integral part of the terms of the 2008 Permission.1 The extant permission has also been misrepresented as the new buildings were replacements and there was no increase to the footprint under those plans. -

LOCAL GOVERNMENT Reform in KĀPITI – What Do You Think? 1

LOCAL GOVERNMENT REFORM IN KĀPITI – WHAT DO YOU THINK? 1 LOCAL GOVERNMENT REFORM IN KĀPITI – WhaT DO YOU THINK? kapiticoast.govt.nz/reform 2 LOCAL GOVERNMENT REFORM IN KĀPITI – WHAT DO YOU THINK? WE WANT TO HEAR FROM AS MANY RESIDENTS AS POSSIBLE LOCAL GOVERNMENT REFORM IN KĀPITI – WHAT DO YOU THINK? 3 Introduction This discussion document has been released by the Kāpiti Coast District Council to help find out how residents want their district to be governed in the future. This document seeks to stimulate discussion and identify whether you want changes to how local government operates in Kāpiti and what you broadly want that change to look like. There are many ways that local government is affected in one way or another by the could be structured in the wider area. However services provided by local government, we in order to have a reasonably focussed debate have described the four options at a fairly high we have identified four options that represent level, without too much detail. We have also different degrees of change. Option 1 contains 2 consciously decided not to express either a sub-options. There is the opportunity for you to preferred option or any views on the advantages discuss other options if you choose. and disadvantages of each option – we are asking the public to do that for us at this stage. Our four options range from keeping the current councils in place but making formal It is not our role to tell other parts of the region arrangements to share services across councils how they should be governed. -

Appropriate Assessment Main Document

Appropriate Assessment of the Hastings Core Strategy Final March 2010 Prepared for Hastings Borough Council Hastings Borough Council Appropriate Assessment of the Hastings Core Strategy Revision Schedule Appropriate Assessment of the Hastings Core Strategy March 2010 Rev Date Details Prepared by Reviewed by Approved by 01 15/03/10 Draft for client Dr James Riley Dr Jo Hughes Dr Jo Hughes review Principal Ecologist Technical Director Technical Director (Ecology) (Ecology) Scott Wilson Scott House Alencon Link Basingstoke This document has been prepared in accordance with the scope of Scott Wilson's Hampshire appointment with its client and is subject to the terms of that appointment. It is addressed to and for the sole and confidential use and reliance of Scott Wilson's client. Scott Wilson RG21 7PP accepts no liability for any use of this document other than by its client and only for the purposes for which it was prepared and provided. No person other than the client may copy (in whole or in part) use or rely on the contents of this document, without the prior Tel: 01256 310200 written permission of the Company Secretary of Scott Wilson Ltd. Any advice, opinions, or recommendations within this document should be read and relied upon only in the context Fax: 01256 310201 of the document as a whole. The contents of this document do not provide legal or tax advice or opinion. © Scott Wilson Ltd 2008 Hastings Borough Council Appropriate Assessment of the Hastings Core Strategy Table of Contents 1 Introduction .........................................................................................1 1.1 Current legislation............................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Scope and objectives....................................................................................................... -

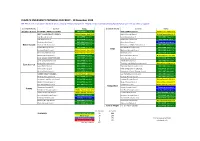

Progress Summary

CLIMATE EMERGENCY PROGRESS CHECKLIST - 10 December 2019 NB. This is work in progress! We have almost certainly missed some actions. Please contact [email protected] with any news or updates. County/Authority Council Status County/Authority Council Status Brighton & Hove BRIGHTON & HOVE CITY COUNCIL DECLARED Dec 2018 KENT COUNTY COUNCIL Motion Passed May 2019 WEST SUSSEX COUNTY COUNCIL Motion Passed - April 2019 Ashford Borough Council Motion Passed July 2019 Adur Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Canterbury City Council DECLARED July 2019 Arun District Council DECLARED Nov 2019 Dartford Borough Council DECLARED Oct 2019 Chichester City Council DECLARED June 2019 Dover District Council Campaign in progress West Sussex Chichester District Council DECLARED July 2019 Folkestone and Hythe District Council DECLARED July 2019 Crawley Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Gravesham Borough Council DECLARED June 2019 Kent Horsham District Council Motion Passed - June 2019 Maidstone Borough Council DECLARED April 2019 Mid Sussex District Council Motion Passed - June 2019 Medway Council DECLARED April 2019 Worthing Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Sevenoaks District Council Motion Passed - Nov 2019 EAST SUSSEX COUNTY COUNCIL DECLARED Oct 2019 Swale Borough Council DECLARED June 2019 Eastbourne Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Thanet District Council DECLARED July 2019 Hastings Borough Council DECLARED Dec 2018 Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council Motion Passed July 2019 East Sussex Lewes District Council DECLARED July 2019 Tunbridge -

Brief-To-Advise-Frome-Town-Council-In-The-Run-Up-To-And-Establishment-Of-Unitary-Authority.Pdf

Unitary Adviser Brief Frame Town Council Brief to advise Frame Town Council in the run up to and establishment of unitary authority(ies) in Somerset 1. Scope Frame Town Council is recognised locally, nationally and internationally as a forward thinking and innovative Council. We are renowned for exploring how to expand the remit of town councils. Somerset is about to embark on local government reorganisation. The county council and the district councils will be replaced with one or two unitary councils in April 2023. FTC sees this as an opportunity to change the way local government in Somerset works towards a more community led approach where decisions are made at the appropriate level and with the appropriate engagement. Influencing how the new unitary is established and developed is a key project for the Council. We want to appoint an experienced advisor or small consultancy to work with FTC Cllrs and staff and other relevant organisations in and beyond Fro me. This work is likely to last at least until September or October 2021 and we anticipate 2 to 3 working days per week. We will be interested in someone who understands local government, has worked at a senior level in relevant organisations, who understands large scale change programmes and ideally also has recent experience of local government reorganisation. The ability to build excellent working relationships at all levels of local government and business will be essential. With other Somerset based parish sector organisations, FTC commissioned a report (here) last year which explores the possibilities of reorganisation. Its seven recommendations have been accepted by both proposals presented to the Government: One Somerset (here) promoted by the County Council, and Stronger Somerset (here) promoted by the four district Councils. -

Kent Housing Group's Housing, Health and Social Sub Group Meeting

Kent Housing Group’s Housing, Health and Social Sub Group Meeting Monday 9 March 2020 Held at Council Chamber, Ashford Borough Council, Civic Centre, Tannery Lane, Ashford TN23 1PL Attendance: Hayley Brooks Sevenoaks District Council Brian Horton South East Local Enterprise Partnership (SELEP) Ashley Jackson Thanet District Council Anne Tidmarsh KCC Linda Smith Public Health Jane Miller KCC Mark James Ashford Borough Council Mark Foster Kent, Surrey, Sussex Community Rehabilitation Company Hazel Skinner Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council Marie Royle CCC Duncan Wilson West Kent Housing Association Niki Melville Town and Country Housing Rebecca Smith Kent Housing Group Sarah Tickner Kent Housing Group Nigel Bucklow Maidstone Borough Council Apologies: John Littlemore, Maidstone Borough Council Sarah Martin, KCHFT, Linda Hibbs, Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council Jane Lang, Tunbridge Wells Borough Council Helen Charles, Town and Country Chair: Hayley Brooks Points of note and actions agreed: 1. Welcome and introduction 2. Minutes and Matters Arising 2.1 Brian Horton is a member of sub group representing SELEP and this correction ST shall be reflected in the notes. 2.2 Actions from the last meeting are picked up within this meeting’s agenda. 1 3. Update on the Sub Group Action Plan Sarah shared updates on work delivered over the past eight weeks and since our last meeting. Points of note / Call to Action from Members: 3.1 Links have been made with the Private Sector Housing Sub Group and we are in progress to align actions within our action plans because many of our health themes also align with their client group. -

Vol. 44 No. 2 Page 36 LONDON BOROUGH of LEWISHAM

Vol. 44 No. 2 Page 36 LONDON BOROUGH OF LEWISHAM MEETING OF THE COUNCIL 26 MAY 20 10 Minutes of the Annual General Meeting of the Council of the London Borough of Lewisham held in the Council Chamber, Lewisham Town Hall, Catford, SE6 4RU on WEDNESDAY, 26 MAY 20 10 at 7 .30 p.m. Present Chair of Council (Councillor Anderson ) The Mayor (Sir Steve Bullock) COUNCILLORS ADDISON, J.A. FEAKES, A. MASLIN, P. AFFIKU, A. FITZSIMMONS, P. MILLBANK, J. ALLISON, C. FLETCHER, J. MORRISON, P. AMRANI, S. FOLORUNSO, J. MULDOON, J. BECK, P. FOREMAN, P. NISBET, M. BELL, P. FOXCROFT, V. ONUEGBU, C. BEST, C. GIBSON, H. OWOLABI -OLUYOLE, S. BONAVIA, K. GRIESENBECK, S. PADMORE, S. BOWEN, J. HALL, A. PASCHOUD, J. BRITTON, D. HARRIS, M. PATTISSON, P. BROOKS, D. IBITSON, A. PEAKE, P. CLARKE , S. JEFFREY, S. SHAND, T. CLUTTEN, J. JOHNSON, D. SMITH, A. CURRAN, L. KLIER, H. STAMIROWSKI, E. DABY, J. LONG, M. STOCKBRIDGE, R. DAVIS, V. MAINES, C. TILL, A. DE RYK, A. MALLORY, J. WISE, S. EGAN, D. Apologies Apologies for absence were received from Councillor Whittle. 37 1. Election of Chair of Council RESOLVED that Councillor Madeliene Long be elected Chair of Council for the municipal year 20 10/ 11 . Councillor Long in the Chair 2. Appointment of Vice -Chair of Council RESOLVED that Councillor Michael Harris be elected as Vice -Chair of Council for the municipal year 20 10 /11 . 3. Election of Mayor RESOLVED that the report concerning the election of Sir Steve Bullock as Mayor be noted. 4. Election of Councillors RESOL VED that the report detailing the election of 54 Councillors be noted. -

City Villages: More Homes, Better Communities, IPPR

CITY VILLAGES MORE HOMES, BETTER COMMUNITIES March 2015 © IPPR 2015 Edited by Andrew Adonis and Bill Davies Institute for Public Policy Research ABOUT IPPR IPPR, the Institute for Public Policy Research, is the UK’s leading progressive thinktank. We are an independent charitable organisation with more than 40 staff members, paid interns and visiting fellows. Our main office is in London, with IPPR North, IPPR’s dedicated thinktank for the North of England, operating out of offices in Newcastle and Manchester. The purpose of our work is to conduct and publish the results of research into and promote public education in the economic, social and political sciences, and in science and technology, including the effect of moral, social, political and scientific factors on public policy and on the living standards of all sections of the community. IPPR 4th Floor 14 Buckingham Street London WC2N 6DF T: +44 (0)20 7470 6100 E: [email protected] www.ippr.org Registered charity no. 800065 This book was first published in March 2015. © 2015 The contents and opinions expressed in this collection are those of the authors only. CITY VILLAGES More homes, better communities Edited by Andrew Adonis and Bill Davies March 2015 ABOUT THE EDITORS Andrew Adonis is chair of trustees of IPPR and a former Labour cabinet minister. Bill Davies is a research fellow at IPPR North. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The editors would like to thank Peabody for generously supporting the project, with particular thanks to Stephen Howlett, who is also a contributor. The editors would also like to thank the Oak Foundation for their generous and long-standing support for IPPR’s programme of housing work. -

Surrey Landscape Character Assessment Figures 1-9-2015

KEY km north 0 1 2 3 4 5 Surrey District and Borough boundaries Natural England National Character Areas: Hampshire Downs (Area 130) High Weald (Area 122) Inner London (Area 112) Low Weald (Area 121) Spelthorne North Downs (Area 119) North Kent Plain (Area 113) Northern Thames Basin (Area 111) Thames Basin Heaths (Area 129) Runnymede Thames Basin Lowlands (Area 114) Thames Valley (Area 115) Wealden Greensand (Area 120) Elmbridge © Na tu ral Englan d copy righ t 201 4 Surrey Heath Epsom and Ewell Woking Reigate and Banstead Guildford Tandridge Mole Valley Waverley CLIENT: Surrey County Council & Surrey Hills AONB Board PROJECT: Surrey Landscape Character Assessm ent TITLE: Natural England National Character Areas SCALE: DATE: 1:160,000 at A3 September 2014 595.1 / 50 1 Figure 1 Based on Ordnance Survey mapping with permission of Her Majesty's Stationery Office Licence no. AR187372 © hankinson duckett associates The Stables, Howbery Park, Benson Lane, Wallingford, OX10 8B A t 01491 838175 e [email protected] w www.hda-enviro.co.uk Landscape Architecture Masterplanning Ecology KEY km north 0 1 2 3 4 5 Surrey District and Borough boundaries Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB): Surrey Hills AONB High Weald AONB Kent Downs AONB National Park: Spelthorne South Downs National Park Runnymede Elmbridge Surrey Heath Epsom and Ewell Woking Reigate and Banstead Guildford Tandridge Mole Valley Waverley CLIENT: Surrey County Council & Surrey Hills AONB Board PROJECT: Surrey Landscape Character Assessm ent TITLE: Surrey Districts & Boroughs, AONBs & National Park SCALE: DATE: 1:160,000 at A3 September 2014 595.1 / 50 2 Figure 2 Based on Ordnance Survey mapping with permission of Her Majesty's Stationery Office Licence no. -

Local Government Collaboration in Surrey

WAVERLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL COUNCIL 23 FEBRUARY 2021 Title: Local Government Collaboration in Surrey Portfolio Holder: Cllr J Ward, Leader Senior Officer: T Horwood, Chief Executive Key decision: No Access: Public 1. Purpose and summary 1.1 The purpose of this report is to update the Council on progress on local government collaboration since the Council and Executive discussions of 22 July and 8 September 2020 respectively, and to allow Council to debate opportunities for future collaboration among local authorities in the light of the KPMG report, and this report. 2. Recommendation The Executive has: 1. Noted the KPMG report on future opportunities for local government in Surrey; 2. Endorsed the development of an initial options appraisal for collaboration with Guildford Borough Council; and 3. Allocated the remaining £15,000 budget previously approved for “a unitary council proposal” to “exploring collaboration opportunities with other councils”. The Executive recommend to the Council that it debate opportunities for future collaboration among local authorities in the light of the KPMG report and this report. 3. Reason for the recommendation 3.1 This report updates councillors and the public on the progress made in the discussions on local government reorganisation and collaboration in Surrey. 3.2 At Executive meetings in 2020, £30,000 was allocated “to support preparatory work for a unitary council proposal”. It is now recommended to allocate the remaining £15,000 to support the development of proposals for council collaboration, to be reported back to the Executive in due course. 4. Background context 4.1 A detailed update was provided to the Executive at its meeting on 8 September 2020,1 and is summarised as follows. -

Lewisham Climate Emergency Strategic Action Plan 2020-2030

Lewisham Climate Emergency Strategic Action Plan 2020-2030 1 Joint Foreword by the Mayor of Lewisham, Damien Egan, Cabinet Lead, Sophie McGeevor, and the Young Mayor, Femi Komolafe Society faces a climate and ecological crisis that is the legacy of a generation of inaction. The declaration of a Climate Emergency by Lewisham Council, and hundreds of other organisations up and down the country, is the first step in answer to the call for a new response to this crisis. The difference in the impetus for change is that this call for action has come from citizens, and particularly from young people, internationally, but also here in the borough. Collectively we have an obligation to future generations. We also have a duty to protect the most vulnerable members of our society. Globally, and locally, the oldest, youngest, the least well off and those with health conditions will bear the brunt of a changing climate. As a society our way of living needs to be based around a new contract. A contract that ensures government, business, media, communities and individuals are accountable for their actions and choices, and that we find the way to balance the demands of today against the needs of the future. Meeting this challenge will fundamentally change how we live, but if it is to be successful, this change will not be about giving things up: instead it will be a way to enrich our lives. Taking strong action on energy, carbon and our environment means our air will be cleaner, our homes warmer, we will feel healthier, and we will live in places designed for people with green spaces teeming with life. -

Rother Valley Railway Economic Impacts Report

Report September 2018 Rother Valley Railway Economic Impacts Report Rother Valley Railway Limited Our ref: 22707603 Report September 2018 Rother Valley Railway Economic Impacts Report Prepared by: Prepared for: Steer Rother Valley Railway Limited 28-32 Upper Ground London SE1 9PD +44 20 7910 5000 www.steergroup.com Our ref: 22707603 Steer has prepared this material for Rother Valley Railway Limited. This material may only be used within the context and scope for which Steer has prepared it and may not be relied upon in part or whole by any third party or be used for any other purpose. Any person choosing to use any part of this material without the express and written permission of Steer shall be deemed to confirm their agreement to indemnify Steer for all loss or damage resulting therefrom. Steer has prepared this material using professional practices and procedures using information available to it at the time and as such any new information could alter the validity of the results and conclusions made. Rother Valley Railway Economic Impacts Report | Report Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. i The Rother Valley Railway ‘Missing Link’ ............................................................................ i Local Economic Context ......................................................................................................ii Transport Impacts – Operational Stage.............................................................................