An Investigation of International Courts' Public Authority and Its

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cracked Colonial Foundations of a Neo-Colonial Constitution

1 THE CRACKED COLONIAL FOUNDATIONS OF A NEO-COLONIAL CONSTITUTION Klearchos A. Kyriakides This working paper is based on a presentation delivered at an academic event held on 18 November 2020, organised by the School of Law of UCLan Cyprus and entitled ‘60 years on from 1960: A Symposium to mark the 60th anniversary of the establishment of the Republic of Cyprus’. The contents of this working paper represent work in progress with a view to formal publication at a later date.1 A photograph of the Press and Information Office, Ministry of the Interior, Republic of Cyprus, as reproduced on the Official Twitter account of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Cyprus, 16 August 2018, https://twitter.com/cyprusmfa/status/1030018305426432000 ©️ Klearchos A. Kyriakides, Larnaca, 27 November 2020 1 This working paper reproduces or otherwise contains Crown Copyright materials and other public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0, details of which may be viewed on the website of the National Archives of the UK, Kew Gardens, Surrey, at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/opengovernment-licence/version/3/ This working paper also reproduces or otherwise contains British Parliamentary Copyright material and other Parliamentary information licensed under the Open Parliament Licence, details of which may be viewed on the website of the Parliament of the UK at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/ 2 Introduction This working paper has one aim. It is to advance a thesis which flows from a formidable body of evidence. At the moment when the Constitution of the Republic of Cyprus (‘the 1960 Constitution’) came into force in the English language at around midnight on 16 August 1960, it stood on British colonial foundations, which were cracked and, thus, defective. -

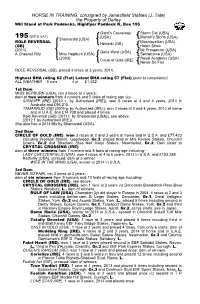

J. Tate) the Property of Darley Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock K, Box 195

HORSE IN TRAINING, consigned by Jamesfield Stables (J. Tate) the Property of Darley Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Highflyer Paddock K, Box 195 Giant's Causeway Storm Cat (USA) 195 (WITH VAT) (USA) Mariah's Storm (USA) Shamardal (USA) ROLE REVERSA L Machiavellian (USA) Helsinki (GB) (GB) Helen Street (2011) Mr Prospector (USA) Gone West (USA) A Chesnut Filly Miss Hepburn (USA) Secrettame (USA) (2003) Royal Academy (USA) Circle of Gold (IRE) Never So Fair ROLE REVERSAL (GB), placed 4 times at 3 years, 2014. Highest BHA rating 62 (Flat) Latest BHA rating 57 (Flat) (prior to compilation) ALL WEATHER 5 runs 4 pl £1,532 1st Dam MISS HEPBURN (USA), ran 3 times at 2 years; dam of two winners from 4 runners and 5 foals of racing age viz- SIGNOFF (IRE) (2010 c. by Authorized (IRE)), won 6 races at 3 and 4 years, 2014 in Australia and £96,215. TAMARRUD (GB) (2009 g. by Authorized (IRE)), won 2 races at 2 and 4 years, 2013 at home and in U.A.E. and £14,738 and placed 4 times. Role Reversal (GB) (2011 f. by Shamardal (USA)), see above. (2012 f. by Authorized (IRE)). She also has a 2013 filly by Shamardal (USA). 2nd Dam CIRCLE OF GOLD (IRE) , won 3 races at 2 and 3 years at home and in U.S.A. and £77,423 including Prestige Stakes, Goodwood, Gr.3 , placed third in Mrs Revere Stakes, Churchill Downs, Gr.2 and Shadwell Stud Nell Gwyn Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.3 ; Own sister to CRYSTAL CROSSING (IRE) ; dam of three winners from 7 runners and 8 foals of racing age including- LADY CHESTERFIELD (USA) , won 4 races at 4 to 6 years, 2013 in U.S.A. -

Ascot Racecourse & World Horse Racing International Challengers

Ascot Racecourse & World Horse Racing International Challengers Press Event Newmarket, Thursday, June 13, 2019 BACKGROUND INFORMATION FOR ROYAL ASCOT 2019 Deirdre (JPN) 5 b m Harbinger (GB) - Reizend (JPN) (Special Week (JPN)) Born: April 4, 2014 Breeder: Northern Farm Owner: Toji Morita Trainer: Mitsuru Hashida Jockey: Yutaka Take Form: 3/64110/63112-646 *Aimed at the £750,000 G1 Prince Of Wales’s Stakes over 10 furlongs on June 19 – her trainer’s first runner in Britain. *The mare’s career highlight came when landing the G1 Shuka Sho over 10 furlongs at Kyoto in October, 2017. *She has also won two G3s and a G2 in Japan. *Has competed outside of Japan on four occasions, with the pick of those efforts coming when third to Benbatl in the 2018 G1 Dubai Turf (1m 1f) at Meydan, UAE, and a fast-finishing second when beaten a length by Glorious Forever in the G1 Longines Hong Kong Cup (1m 2f) at Sha Tin, Hong Kong, in December. *Fourth behind compatriot Almond Eye in this year’s G1 Dubai Turf in March. *Finished a staying-on sixth of 13 on her latest start in the G1 FWD QEII Cup (1m 2f) at Sha Tin on April 28 when coming from the rear and meeting trouble in running. Yutaka Take rode her for the first time. Race record: Starts: 23; Wins: 7; 2nd: 3; 3rd: 4; Win & Place Prize Money: £2,875,083 Toji Morita Born: December 23, 1932. Ownership history: The business owner has been registered as racehorse owner over 40 years since 1978 by the JRA (Japan Racing Association). -

Race 1 1 1 2 2 3 2 4 3 5 3 6 4 7 4 8 5 9 5 10

NAKAYAMA SUNDAY,OCTOBER 4TH Post Time 10:05 1 ! Race Dirt 1200m TWO−YEAR−OLDS Course Record:6Dec.09 1:10.2 DES,WEIGHT FOR AGE,MAIDEN Value of race: 9,680,000 Yen 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th Added Money(Yen) 5,100,000 2,000,000 1,300,000 770,000 510,000 Stakes Money(Yen) 0 0 0 Ow. Tomoyuki Nakamura 770,000 S 20002 Life40004M 20002 1 1 B 55.0 Yuichiro Nishida(0.8%,1−2−4−121,133rd) Turf40004 I 00000 Maradona(JPN) Dirt00000L 00000 .Pelusa(0.05) .Kane Hekili C2,ch. Takaki Iwato(4.9%,11−20−10−183,113rd) Course00000E 00000 Wht. /Maradona Spin /Bambina Coco 23Feb.18 Bamboo Stud Wet 00000 2Aug.20 NIIGATA MDN T1200Fi 11 13 1:11.8 18th/18 Yuichiro Nishida 54.0 468' Nishino Adjust 1:10.1 <3/4> Tosen Gaia <1/2> Meiner Amistad 19Jul.20 FUKUSHIMA MDN T1200Fi 7 6 1:11.3 4th/11 Yuichiro Nishida 54.0 468% Seiun Deimos 1:10.2 <2 1/2> Longing Birth <4> High Priestess 5Jul.20 FUKUSHIMA MDN T1800Yi 45310 1:54.0 11th/11 Yukito Ishikawa 54.0 466' Cosmo Ashura 1:50.2 <NK> Magical Stage <NK> Seiun Gold 20Jun.20 TOKYO NWC T1400Go 4 4 1:24.9 7th/16 Yukito Ishikawa 54.0 466* Cool Cat 1:23.4 <2> Songline <1 1/4> Bisboccia Ow. Toshio Isobe 0 S 20002 Life20002M 00000 1 2 53.0 Akira Sugawara(4.5%,18−25−31−324,48th) Turf00000 I 00000 Isoei Hikari(JPN) Dirt20002L 00000 .A Shin Hikari(0.54) .South Vigorous C2,b. -

Maxplanckresearch 1/2019

B56133 The Science Magazine of the Max Planck Society 1.2019 Europe ECONOMIC SOCIOLOGY TSUNAMI RESEARCH CHEMISTRY MOBILITY The power of Atoms make Material mix from Buses on expectations waves the food processor demand Daniel Hincapié, Research Engineer at Fraunhofer Institute, Munich “Germany, Austria and Switzerland are known for their outstanding research opportunities. And academics.com is my go-to portal for job postings.” Jobs for bight minds academics.com is the No. 1 job listings site for science and research in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Visit academics.com and discover a rich variety of attractive positions at universities and other organisations, plus comprehensive career advice. Register now and bene t from our free job o ers and services at: www.academics.com ON LOCATION Treasuries of knowledge Scholars immersed in contemplative silence and surrounded by books – for centuries, they were the personification of learning. But can libraries still function as central “research locations” when the digital age has seen most sources made available online? Researchers worldwide would answer this question with a clear “yes.” The printed book is still the preferred publication medium in many areas of knowledge, while libraries can be seen as well-equipped labs without which no research would be possible. It therefore comes as no surprise that guest scientists often have to plan their stays at the Max Planck Institutes according to the capacities available for library use. However, the quality of a library is not judged solely by its collections, as valuable as these may be. It is the accessibility of the knowledge that matters. -

ZACHARY D. KAUFMAN, J.D., Ph.D. – C.V

ZACHARY D. KAUFMAN, J.D., PH.D. (203) 809-8500 • ZACHARY . KAUFMAN @ AYA . YALE. EDU • WEBSITE • SSRN ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS SCHOOL OF LAW (Jan. – May 2022) Visiting Associate Professor of Law UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON LAW CENTER (July 2019 – present) Associate Professor of Law and Political Science (July 2019 – present) Co-Director, Criminal Justice Institute (Aug. 2021 – present) Affiliated Faculty Member: • University of Houston Law Center – Initiative on Global Law and Policy for the Americas • University of Houston Department of Political Science • University of Houston Hobby School of Public Affairs • University of Houston Elizabeth D. Rockwell Center on Ethics and Leadership STANFORD LAW SCHOOL (Sept. 2017 – June 2019) Lecturer in Law and Fellow EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD – D.Phil. (Ph.D.), 2012; M.Phil., 2004 – International Relations • Marshall Scholar • Doctoral Dissertation: From Nuremberg to The Hague: United States Policy on Transitional Justice o Passed “Without Revisions”: highest possible evaluation awarded o Examiners: Professors William Schabas and Yuen Foong Khong o Supervisors: Professors Jennifer Welsh (primary) and Henry Shue (secondary) o Adaptation published (under revised title) by Oxford University Press • Master’s Thesis: Explaining the United States Policy to Prosecute Rwandan Génocidaires YALE LAW SCHOOL – J.D., 2009 • Editor-in-Chief, Yale Law & Policy Review • Managing Editor, Yale Human Rights & Development Law Journal • Articles Editor, Yale Journal of International Law -

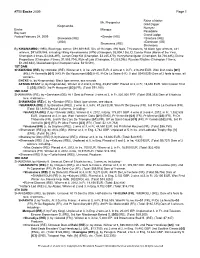

750 Encke 2009 Page 1

#750 Encke 2009 Page 1 Raise a Native Mr. Prospector Gold Digger Kingmambo Nureyev Encke Miesque Pasadoble Bay Colt Grand Lodge Foaled February 24, 2009 =Sinndar (IRE) Shawanda (IRE) =Sinntara (IRE) (2002) =Darshaan (GB) Shamawna (IRE) Shamsana By KINGMAMBO (1990), Black type winner, $91,608,945. Sire of 16 crops. 892 foals, 718 starters, 84 black type winners, 441 winners, $91,608,945, including =King Kamehameha (JPN) (Champion, $3,904,136), El Condor Pasa (Horse of the Year, Champion 3 times, $3,468,397), Lemon Drop Kid (Champion, $3,245,370), Henrythenavigator (Champion, $2,746,485), Divine Proportions (Champion 3 times, $1,553,704), Rule of Law (Champion, $1,323,096), Russian Rhythm (Champion 3 times, $1,260,634), Walzerkoenigin (Champion twice, $410,591). 1ST DAM SHAWANDA (IRE), by =Sinndar (IRE). Winner at 3, in Ire, 225,200 EUR. 4 wins at 3, in Fr, 216,450 EUR. Won Irish Oaks [G1] (IRE), Pr Vermeille [G1] (FR), Pr De Royaumont [G3] (FR), Pr De La Seine (FR). (Total: $540,029) Dam of 2 foals to race, all winners-- ENCKE (c, by Kingmambo). Black type winner, see records. GENIUS BEAST (c, by Kingmambo). Winner at 2 and 3, in Eng, 43,857 GBP. Placed at 3, in Fr, 13,650 EUR. Won Classic Trial S. [G3] (ENG). 3rd Pr Hocquart [G2] (FR). (Total: $91,160) 2ND DAM SHAMAWNA (IRE), by =Darshaan (GB). At 1 Sent to France. 2 wins at 3, in Fr, 220,000 FRF. (Total: $39,393) Dam of 6 foals to race, 4 winners-- SHAWANDA (IRE) (f, by =Sinndar (IRE)). -

El Futuro De La Unión Europea. Retos Y Desafíos

El futuro de la Unión Europea. Retos y desafíos 08.Jul - 10.Jul Cod. D06-19 Edition 2019 Activity type Course Date 08.Jul - 10.Jul Location Miramar Palace Languages Spanish Academic Validity 30 hours MANAGEMENT Juan Ignacio Ugartemendia Eceizabarrena, UPV/EHU Daniel Sarmiento Ramírez-Escudero, Universidad Complutense de Madrid Organising Committee 1 Description El Curso tiene por objeto profundizar en el estudio del futuro de la Unión Europea, ahora que ha transcurrido el primer cuarto de siglo desde la entrada en vigor, allá por noviembre de 1993, del Tratado que la fundaba, así como la primera década de aplicación de su Carta de Derechos Fundamentales. Para ello se tomará en consideración la perspectiva de algunos de los principales retos y desafíos que han surgido en el seno de la misma y a los que debe hacer frente. Participará profesorado de diversas universidades e institutos nacionales y extranjeros, así como miembros de varias instituciones europeas (Tribunal de Justicia, Consejo de la Unión, o Banco Central Europeo). Uno de los bloques temáticos a tratar es el referido a los desafíos que pueden presentarse en el ámbito institucional de la Unión Europea, recién celebradas las elecciones al Parlamento Europeo de mayo de 2019, ante la elección de una nueva Comisión Europea, y debiendo tener en cuenta los eventuales cambios que vendrán derivados del Brexit. Otro de los temas que se abordará en profundidad es el concerniente a algunos de los principales desafíos en materia de Unión Económica y Monetaria. La lucha por el Estado de Derecho en la Unión Europea será también un campo a explorar, examinando los problemas generados, por ejemplo, en relación a los ataques que ha sufrido la independencia judicial en algunos países de la Unión, o estudiando el papel del Estado de Derecho en los Tratados de la Unión. -

FIVE DIAMONDS Barn 2 Hip No. 1

Consigned by Three Chimneys Sales, Agent Barn Hip No. 2 FIVE DIAMONDS 1 Dark Bay or Brown Mare; foaled 2006 Seattle Slew A.P. Indy............................ Weekend Surprise Flatter................................ Mr. Prospector Praise................................ Wild Applause FIVE DIAMONDS Cyane Smarten ............................ Smartaire Smart Jane........................ (1993) *Vaguely Noble Synclinal........................... Hippodamia By FLATTER (1999). Black-type-placed winner of $148,815, 3rd Washington Park H. [G2] (AP, $44,000). Sire of 4 crops of racing age, 243 foals, 178 starters, 11 black-type winners, 130 winners of 382 races and earning $8,482,994, including Tar Heel Mom ($472,192, Distaff H. [G2] (AQU, $90,000), etc.), Apart ($469,878, Super Derby [G2] (LAD, $300,000), etc.), Mad Flatter ($231,488, Spend a Buck H. [G3] (CRC, $59,520), etc.), Single Solution [G3] (4 wins, $185,039), Jack o' Lantern [G3] ($83,240). 1st dam SMART JANE, by Smarten. 3 wins at 3 and 4, $61,656. Dam of 7 registered foals, 7 of racing age, 7 to race, 5 winners, including-- FIVE DIAMONDS (f. by Flatter). Black-type winner, see record. Smart Tori (f. by Tenpins). 5 wins at 2 and 3, 2010, $109,321, 3rd Tri-State Futurity-R (CT, $7,159). 2nd dam SYNCLINAL, by *Vaguely Noble. Unraced. Half-sister to GLOBE, HOYA, Foamflower, Balance. Dam of 6 foals to race, 5 winners, including-- Taroz. Winner at 3 and 4, $26,640. Sent to Argentina. Dam of 2 winners, incl.-- TAP (f. by Mari's Book). 10 wins, 2 to 6, 172,990 pesos, in Argentina, Ocurrencia [G2], Venezuela [G2], Condesa [G3], General Lavalle [G3], Guillermo Paats [G3], Mexico [G3], General Francisco B. -

77-803 ) John Barchi, )

ORIGINAL In the Supreme Court of tfje Utiiteb States WILLIAM Go BARRYs AS CHAIRMAN OP ) THE NEW YORK STATE RACING AND ) WAGERING BOARD, ET AL,, ) ) APPELLANTS, ) ) V, ) No. 77-803 ) JOHN BARCHI, ) APPELLEE„ <X> -rt0 c5 t/> rn to I> rn ^ ;/>— o0 <— "O —.ezrn tj-'1 4> of my) O Washington, Da C, November 7, 1978 Pages 1 thru 48 Duplication or copying of this transcript by photographic, electrostatic or other facsimile means is prohibited under the order form agreement. ^Jloouer Ideportint^ do., d)nc. i! /^ejjorfero WuJ. teflon, 7). d. 546-6666 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE 'UNITED STATES *<r WILLIAM Go BARRY, AS CHAIRMAN OF: THE NEW YORK STATE RACING AND : WAGERING BOARD, ET AL„, : a Appellants, : V o No» 77-303 JOHN BARCHI, Appellee» : ------ x Washington, D„ C„ Tuesday, November 7s 1973 The above-entitled matter came on for argument at 11:53 o'clock, a0mo BEFORE: WARREN Bo BURGER, Chief Justice of the United States WILLIAM BRENNAN, Associate Justice POTTER STEWART, Associate Justice BYRON Ro ’WHITE, Associate Justice THURGOQD MARSHALL, Associate Justice HARRY A 0 BLACKMUN, Associate Justice LEWIS Fo POWELL, JR,, Associate Justice WILLIAM Ho REHNQUIST, Associate Justice JOHN PAUL STEVENS, Associate Justice APPEARANCES : ROBERT So HAMMER, ESQ,, Assistant Attorney General, State of New York, Two World Trade Center, New York, New York 10047* on behalf of the Appellants, JOSEPH A0 FARALDO, ESQ„, 125-10 Queens Boulevard, Kew Gardens, New York 11415, on behalf of the Appellee 2 CONTENT^ ORAL ARGUMENT OP: PAGE Robert Hammer* Esq„* on behalf of the Appellants 3 In rebuttal 45 Joseph A „ Faraldo, Esq.* on behalf of the Appellees 23 3 MRo CHIEF JUSTICE BURGER: We will hear arguments next in 77-803» Barry against Barchi. -

By Mr Armin Von BOGDANDY (Director, Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, Heidelberg and Mr Jochen Von BERNSTORFF, Germany)

Strasbourg, 5 May 2010 CDL-UD(2010)010 Engl. Only EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) in co-operation with THE FACULTY OF LAW AND THE CLUSTER OF EXCELLENCE “FORMATION OF NORMATIVE ORDERS” OF GOETHE UNIVERSITY, FRANKFURT AM MAIN, GERMANY and with THE CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE IN FOUNDATIONS OF EUROPEAN LAW AND POLITY RESEARCH HELSINKI UNIVERSITY, FINLAND UNIDEM SEMINAR “DEFINITION AND DEVELOPMENT OF HUMAN RIGHTS AND POPULAR SOVEREIGNTY IN EUROPE” Frankfurt am Main, Germany 15 – 16 May 2009 “THE EU FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS AGENCY WITHIN THE EUROPEAN AND INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS ARCHITECTURE: THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND SOME UNSETTLED ISSUES IN A NEW FIELD OF ADMINISTRATIVE LAW” by Mr Armin von BOGDANDY (Director, Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, Heidelberg and Mr Jochen von BERNSTORFF, Germany) This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL-UD(2010)010 - 2 - A. Introduction Establishing the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (hereinafter the "Agency"), which commenced its work on 1 March 2007,1 was another step in the expansion of an EU policy on fundamental rights.2 Pursuant to the – not accidentally contorted – language of Art. 2 of the Regulation establishing the Agency (hereinafter the "Regulation") its objective is "to provide the relevant institutions, bodies, offices and agencies of the Community and its Member States when implementing Community law with assistance and expertise relating to fundamental rights in order to support them when they take measures or formulate courses of action within their respective spheres of competence to fully respect fundamental rights”. -

Pasts, Presents, and a Possible Future.1 Martin Krygier the Rule of Law Is

Paper for seminar co-sponsored by Center for Study of Law & Society, and Kadish Center for Morality, Law & Public Affairs, University of California Berkeley, 2 March 2016. The Rule of Law: Pasts, Presents, and a possible Future.1 Martin Krygier The rule of law is today so totally on every aid donor’s agenda that it has become an unavoidable cliché of international organisations of every kind. More generally, praise for it has infiltrated contemporary political moralising virtually unopposed. It might not do much to quicken the pulse, but it is prescribed for a vast array of other problems. This is a relatively recent occurrence (Krygier 2014), which one would not have predicted as recently as the 1980s – I know; I didn’t. If I’d known the stocks of rule of law would soar as they have, I would have printed money, instead of mere words, to invest in it. But I had no inkling I was talking up a goldmine. This has changed so dramatically, that in virtually every introduction to the subject, the rule of law logo-cliché has come to be joined by three supplementary clichés, meta-clichés as it were, ritual observations about cliché no.1. The first is evidenced in the preceding paragraph: everyone who writes about the rule of law begins by noting its unprecedented voguishness. Second is the observation that, along with popularity has gone promiscuity. It has a huge array of suitors around the world, and it seems happy to hitch up with them all. That has in turn resulted in a third predictable adornment of every contemporary article on the subject: the rule of law now means so many different things to so many different people, it is so ‘essentially contested’ (see Waldron 2002) and likely to remain so, that it is hard to say just what this rhetorical balloon is full of, or indeed where it might float next.