Underwater Communication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Korean Cyber Capabilities: in Brief

North Korean Cyber Capabilities: In Brief Emma Chanlett-Avery Specialist in Asian Affairs Liana W. Rosen Specialist in International Crime and Narcotics John W. Rollins Specialist in Terrorism and National Security Catherine A. Theohary Specialist in National Security Policy, Cyber and Information Operations August 3, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44912 North Korean Cyber Capabilities: In Brief Overview As North Korea has accelerated its missile and nuclear programs in spite of international sanctions, Congress and the Trump Administration have elevated North Korea to a top U.S. foreign policy priority. Legislation such as the North Korea Sanctions and Policy Enhancement Act of 2016 (P.L. 114-122) and international sanctions imposed by the United Nations Security Council have focused on North Korea’s WMD and ballistic missile programs and human rights abuses. According to some experts, another threat is emerging from North Korea: an ambitious and well-resourced cyber program. North Korea’s cyberattacks have the potential not only to disrupt international commerce, but to direct resources to its clandestine weapons and delivery system programs, potentially enhancing its ability to evade international sanctions. As Congress addresses the multitude of threats emanating from North Korea, it may need to consider responses to the cyber aspect of North Korea’s repertoire. This would likely involve multiple committees, some of which operate in a classified setting. This report will provide a brief summary of what unclassified open-source reporting has revealed about the secretive program, introduce four case studies in which North Korean operators are suspected of having perpetrated malicious operations, and provide an overview of the international finance messaging service that these hackers may be exploiting. -

In This Issue: 11 Years All Optical Submarine Network Upgrades Of

66 n o v voice 2012 of the ISSn 1948-3031 Industry System Upgrades Edition In This Issue: 11 Years All Optical Submarine Network Upgrades of Upgrading Cables Systems? More Possibilities That You Originally Think Of! Excellence Reach, Reliability And Return On Investment: The 3R’s To Optimal Subsea Architecture Statistics Issue Issue Issue #64 Issue #3 #63 #2 Released Released Issue Released Released #65 Released 2 ISSN No. 1948-3031 PUBLISHER: Wayne Nielsen MANAGING EDITOR: Kevin G. Summers ovember in America is the month Forum brand which we will be rolling out we celebrate Thanksgiving. It during the course of the year, and which CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: Stewart Ash, is also the month SubTel Forum we believe will further enhance your James Barton, Bertrand Clesca, Dr Herve Fevrier, N Stephen Jarvis, Brian Lavallée, Pete LeHardy, celebrates our anniversary of existence, utility and enjoyment. We’re going to kick Vinay Rathore, Dr. Joerg Schwartz that now being 11 years going strong. it up a level or two, and think you will like the developments . And as always, it will Submarine Telecoms Forum magazine is When Ted and I established our little be done at no cost to our readers. published bimonthly by Submarine Telecoms magazine in 2001, our hope was to get Forum, Inc., and is an independent commercial enough interest to keep it going for a We will do so with two key founding publication, serving as a freely accessible forum for professionals in industries connected while. We had a list of contacts, an AOL principles always in mind, which annually with submarine optical fiber technologies and email address and a song in our heart; the I reaffirm to you, our readers: techniques. -

Never Agains IV February 2010

the Availability Digest www.availabilitydigest.com More Never Agains IV February 2010 It is once again time to reflect on the damage that IT systems can inflict on us mere humans. We have come a long way in ensuring the high availability of our data-processing systems. But as the following stories show, we still have a ways to go. During the last six months, hardware/software and network faults shared responsibility, each causing about one-third of the outages. The rest of the outages were caused by a variety of problems such as power failures, construction mishaps, and hacking. Rackspace Hit with Another Outage Techcrunch, June 20, 2009 – On June 20, Rackspace suffered yet another outage1 due to a power failure. The breaker on the primary utility feed powering one of its nine data centers tripped, causing data center’s generators to start up. However, a field excitation failure escalated to the point that the generators became overloaded. An attempt by Rackspace to fail over to its secondary utility feed failed because the transfer switch malfunctioned. When the data center’s batteries ran out, the data center went down. Failovers do fail. Have a contingency plan no matter the extent of your redundancy. NYSE Suffers Several Outages in Less Than a Month Reuters, July 2, 2009 – On Thursday morning, July 2, brokers on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange found that they could not route orders, causing the NYSE to halt trading in some stocks and to extend the trading day. During the previous month, a software glitch halted trading; and an order-matching problem affected timely order reconciliation. -

Availability Digest

the Availability Digest www.availabilitydigest.com Help! My Data Center is Down! Part 3: Internet Outages December 2011 Long gone are the days of the isolated data center. Back then, batch jobs were submitted to update databases and to generate reports. Back then, turn-around times were measured in hours or even days. In today’s competitive environment, IT services are online; and instant response times are expected. What good is a data center if no one can talk to it? Orders can’t be placed or tracked. Medical records can’t be accessed. Online banking comes to a halt. Today’s data centers must be connected. They depend upon the networks that allow users to access them online reliably and with fast response times. In the old days, a company had control over its communication network. It leased lines that it used exclusively for its purposes. If it lost communications, it had direct access to its communication carrier for rapid repair. For critical applications, companies installed redundant communication facilities so that they could continue in operation even in the presence of a communications failure on one of their lines. Not so true today. More and more, companies are relying on the public Internet to connect their users with company data centers. But how reliable is the Internet? In our previous articles in this series, we related horror stories of unimaginable power failures and storage failures that took down the best-designed data centers. In this article, we explore some notable Internet failures that rendered data centers useless even though they were otherwise fully operational. -

Potential Human Cost of Cyber Operations

ICRC EXPERT MEETING 14–16 NOVEMBER 2018 – GENEVA THE POTENTIAL HUMAN COST OF CYBER OPERATIONS REPORT ICRC EXPERT MEETING 14–16 NOVEMBER 2018 – GENEVA THE POTENTIAL HUMAN COST OF CYBER OPERATIONS Report prepared and edited by Laurent Gisel, senior legal adviser, and Lukasz Olejnik, scientific adviser on cyber, ICRC THE POTENTIAL HUMAN COST OF CYBER OPERATIONS Table of Contents Foreword............................................................................................................................................. 3 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................. 4 Executive summary ............................................................................................................................. 5 Introduction....................................................................................................................................... 10 Session 1: Cyber operations in practice .………………………………………………………………………….….11 A. Understanding cyber operations with the cyber kill chain model ...................................................... 11 B. Operational purpose ................................................................................................................. 11 C. Trusted systems and software supply chain attacks ...................................................................... 13 D. Cyber capabilities and exploits .................................................................................................. -

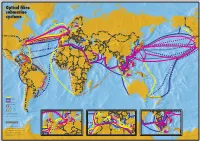

Optical Fibre Submarine Systems

Optical fibre submarine GREENLAND systems D N ALASKA A (USA) ICELAND L Umeå N Vestmannaeyjar BOTNIA I Vaasa F Faroes SWEDEN Rauma RUSSIA 6 x 622 Turku Hallstavik Whittier Valdez Karst 2 + 1 x 2.5 Gbit/s Norrtälje Kingisepp Seward Tallin NORWAY ESTONIA U N Lena I 2 x 560 LATVIA CANTAT-3 T point AC-1 E DENMARK CANADA D Westerland LITHUANIA Northstar 2 x 4 (WDM) x 2.5 Gbit/s TAT-14 K I N REP. OF IRELAND G BELORUSSIA TAT-10 2 + 1 x 560 D S D Norden/ N O LA Grossheide ER POLAND M TH NE GERMANY Gemini North 2 x 6 (WDM) x 2.5 Gbit/s BELGIUM CZECH Dieppe REP. Port UKRAINE Alberni NPC 3 + 1 x 420 St Brieuc SLOVAK REP. M O KAZAKHSTAN L FRANCE D Seattle AC-1 AUSTRIA A V TPC-5 2 x 5 Gbit/s HUNGARY I Tillamook PTAT-1 3 + 1 x 420 Gbit/s SWITZ. I A A Odessa DM) x 2.5 St Hilaire de Riez SLOVEN 2 x 6 (W MONGOLIA i South FLAG Atlantic-1 160 Gbit/s emin CROATIA ROMANIA Pacific G Y I U Novorossijsk City Pennant Point HERZEGOVINABOSNIA- G s T O 2.5 SochiGbit/s PC-1 Medway Harbour Gbit/ S x 5 L TAT-11 3 DxM 560) A Varna Shirley x 3 (W A V Nakhodka TAT-12 2 x 3 (WDM) x 5 Gbit/s 2 I GEORGIA Ishikati TAT-13 A BULGARIA UZBEKISTAN Rhode Island F L PC-1 L ALBANIA Poti A KYRGYZSTAN N Long Island G Y TAT-9 2 + 1 x 560 ARMENIA AZERBAIJAN New York MACEDONIA TURKMENISTAN NORTH Bandon TAT-8 2 x 280 Istanbul KOREA FLAG Atlantic-1 160 Gbit/s Azores SPAIN E R-J-K C 2 x 560 0 EE 6 R 5 G Dalian A CANUS-1 TAT-14 PORTUGAL TURKEY JIH CableProject Japan-US Manasquan Lisbon UNITED STATES 3x TAJIKISTAN Point Sesimbra PC-1 Arena Tuckerton Marmaris Yantaï SOUTH P TPC-4 2 x 560 A S -

Grammar for Academic Writing

GRAMMAR FOR ACADEMIC WRITING Tony Lynch and Kenneth Anderson (revised & updated by Anthony Elloway) © 2013 English Language Teaching Centre University of Edinburgh GRAMMAR FOR ACADEMIC WRITING Contents Unit 1 PACKAGING INFORMATION 1 Punctuation 1 Grammatical construction of the sentence 2 Types of clause 3 Grammar: rules and resources 4 Ways of packaging information in sentences 5 Linking markers 6 Relative clauses 8 Paragraphing 9 Extended Writing Task (Task 1.13 or 1.14) 11 Study Notes on Unit 12 Unit 2 INFORMATION SEQUENCE: Describing 16 Ordering the information 16 Describing a system 20 Describing procedures 21 A general procedure 22 Describing causal relationships 22 Extended Writing Task (Task 2.7 or 2.8 or 2.9 or 2.11) 24 Study Notes on Unit 25 Unit 3 INDIRECTNESS: Making requests 27 Written requests 28 Would 30 The language of requests 33 Expressing a problem 34 Extended Writing Task (Task 3.11 or 3.12) 35 Study Notes on Unit 36 Unit 4 THE FUTURE: Predicting and proposing 40 Verb forms 40 Will and Going to in speech and writing 43 Verbs of intention 44 Non-verb forms 45 Extended Writing Task (Task 4.10 or 4.11) 46 Study Notes on Unit 47 ii GRAMMAR FOR ACADEMIC WRITING Unit 5 THE PAST: Reporting 49 Past versus Present 50 Past versus Present Perfect 51 Past versus Past Perfect 54 Reported speech 56 Extended Writing Task (Task 5.11 or 5.12) 59 Study Notes on Unit 60 Unit 6 BEING CONCISE: Using nouns and adverbs 64 Packaging ideas: clauses and noun phrases 65 Compressing noun phrases 68 ‘Summarising’ nouns 71 Extended Writing Task (Task 6.13) 73 Study Notes on Unit 74 Unit 7 SPECULATING: Conditionals and modals 77 Drawing conclusions 77 Modal verbs 78 Would 79 Alternative conditionals 80 Speculating about the past 81 Would have 83 Making recommendations 84 Extended Writing Task (Task 7.13) 86 Study Notes on Unit 87 iii GRAMMAR FOR ACADEMIC WRITING Introduction Grammar for Academic Writing provides a selective overview of the key areas of English grammar that you need to master, in order to express yourself correctly and appropriately in academic writing. -

A Blue BRICS, Maritime Security, and the South Atlantic François Vreÿ

Contexto Internacional vol. 39(2) May/Aug 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8529.2017390200008 A Blue BRICS, Maritime Security, and the South Atlantic François Vreÿ François Vreÿ* Abstract: Analysts frequently label the BRICS grouping of states (Brazil, India, Russia, China, and South Africa) as primarily an economic club emphasising economic performances as primary ob- jectives. Co-operation of international groupings are rarely, if ever, set within the context of their access to maritime interests, security, and benefits. A second void stems from the lack of emphasis upon the economic benefits of secured maritime domains. In this vein, a common, but neglected aspect of the BRICS grouping’s power and future influence resides in their maritime domains, the value of which ultimately depends upon the responsible governance and use of ocean territories. The maritime interests of BRICS countries only become meaningful if reinforced by maritime se- curity governance and co-operation in the respective oceans. Presently China and India seem to dominate the maritime stage of BRICS, but the South Atlantic is an often overlooked space. For BRICS the value of the South Atlantic stems from how it secures and unlocks the potential of this maritime space through co-operative ventures between Brazil, South Africa as a late BRICS partner, and West African littoral states in particular. Unfortunately, BRICS holds its own maritime tensions, as member countries also pursue competing interests at sea. Keywords: Africa; Brazil; BRICS; Maritime Security; South Atlantic; South Africa. Introduction Contemporary maritime thought prioritises matters that underpin the use of the oceans in more constructive ways, underlines the importance of co-operation, and manages the oceans in a way that promotes sustainability (Petrachenko 2012: 74). -

Broadband Infrastructure in the ASEAN-9 Region

BroadbandBroadband InfrastructureInfrastructure inin thethe ASEANASEAN‐‐99 RegionRegion Markets,Markets, Infrastructure,Infrastructure, MissingMissing Links,Links, andand PolicyPolicy OptionsOptions forfor EnhancingEnhancing CrossCross‐‐BorderBorder ConnectivityConnectivity Michael Ruddy Director of International Research Terabit Consulting www.terabitconsulting.com PartPart 1:1: BackgroundBackground andand MethodologyMethodology www.terabitconsulting.com ProjectProject ScopeScope Between late‐2012 and mid‐2013, Terabit Consulting performed a detailed analysis of broadband infrastructure and markets in the 9 largest member countries of ASEAN: – Cambodia – Indonesia – Lao PDR – Malaysia – Myanmar – Philippines – Singapore – Thailand – Vietnam www.terabitconsulting.com ScopeScope (cont(cont’’d.)d.) • The data and analysis for each country included: Telecommunications market overview and analysis of competitiveness Regulation and government intervention Fixed‐line telephony market Mobile telephony market Internet and broadband market Consumer broadband pricing Evaluation of domestic network connectivity International Internet bandwidth International capacity pricing Historical and forecasted total international bandwidth Evaluation of international network connectivity including terrestrial fiber, undersea fiber, and satellite Evaluation of trans‐border network development and identification of missing links www.terabitconsulting.com SourcesSources ofof DataData • Terabit Consulting has completed dozens of demand studies for -

NETWORK I2i LIMITED

NETWORK i2i LIMITED AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED MARCH 31, 2020 NETWORK i2i LIMITED Contents Page No. 1. Corporate Information 3 2. Commentary of the Directors 4 3. Certificate from the secretary 5 4. Independent Auditor’s Report 7-8 5. Financial Statements - Statement of Comprehensive Income 9 - Statement of Financial Position 10 - Statement of Changes in Equity 11 - Statement of Cash Flows 12 - Notes to Financial Statements 13-54 NETWORK i2i LIMITED CORPORATE INFORMATION Date of Appointment DIRECTORS Bashirali Abdulla Currimjee February 09, 2001 Jantina Catharina Van De Vreede May 22, 2013 Naushad Ally Sohoboo September 06, 2013 Ajay Chitkara August 24, 2015 Rajvardhan Singh Bhullar April 18, 2016 Pravin Surana January 01, 2020 ADMINISTRATOR IQ EQ Corporate Services Mauritius Ltd. AND SECRETARY 33 Edith Cavell Street Port Louis, 11324 Mauritius REGISTERED OFFICE C/o IQ EQ Corporate Services Mauritius Ltd. 33 Edith Cavell Street Port Louis, 11324 Mauritius BANKERS Standard Chartered Bank (Mauritius) Limited 19 Bank Street, 6th floor, Standard Chartered Tower, Cybercity, Ebene, Mauritius – 72201 BNP Paribas, The Netherlands Herengracht, 595 1017, CE Amsterdam AUDITOR Deloitte 7th -8th Floor, Standard Chartered Tower, 19-21 Bank Street, Cybercity, Ebene, 72201, Mauritius 3 NETWORK i2i LIMITED COMMENTARY OF THE DIRECTORS The Directors present their commentary, together with the audited financial statements of Network i2i Limited (the ‘Company ’) for the year ended Mar ch 31, 20 20 . PRINCIPAL ACTIVITY The principal activity of the Company is the operation and provision of telecommunication facilities and services utilising a network of submarine cable systems and associated terrestrial capacity. The network consists of a 3,200 kilometer cable link between Singapore and India. -

No Internet? February 2008

the Availability Digest What? No Internet? February 2008 On Wednesday, January 30, 2008, North Africa, the Middle East, and India experienced a massive Internet outage that was destined to last for several days or even weeks.1 How did this happen? How did companies cope? Could it happen in other areas such as Europe or the United States? The Failure The bulk of data traffic from North Africa, from the Middle Eastern countries, and from India and Pakistan is routed through North Africa. There, it is carried by a set of three submarine cables that lie under the Mediterranean Sea. The cables link Alexandria, Egypt, with Palermo, Italy, where the traffic then moves on to Europe, the UK, and the Eastern United States. On January 30, 2008, two of these three cables were severed. It is not yet known why, but the predominant theory is that the cables were severed by the anchor of a huge freighter. Heavy storms had hit the area the previous day and forced Egyptian authorities to close the northern entrance to the Suez Canal at Alexandria. As a result, ships had to anchor offshore in the Mediterranean Sea, dropping their anchors to ride out the storm. It is suspected that one of the freighters dropped its anchor on top of the cables. Reportedly, the two severed cables were a kilometer apart. The storm may have dragged the freighter’s anchor across the sea bed, thus taking out both cables. The result of this catastrophe was that 75% of channel capacity was lost from the Mideast to Europe and beyond. -

Bharti and Reliance Jio Announce Agreement for International Data Connectivity’ Being Issued by the Company

April 23, 2013 The BSE Limited Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers, Dalal Street, Mumbai-400001 National Stock Exchange of India Limited Exchange Plaza C-1, Block G, Bandra Kurla Complex, Bandra (E), Mumbai-400051 Ref: Bharti Airtel Limited (532454 / BHARTIARTL) Sub: Press Release Dear Sir / Madam, We are enclosing herewith a press release titled ‘Bharti and Reliance Jio announce agreement for international data connectivity’ being issued by the Company. Kindly take the same on record. Thanking you, Sincerely Yours, For Bharti Airtel Limited Sd/- Rajendra Chopra Dy. Company Secretary Encl: As above Bharti Airtel Limited (A Bharti enterprise) Regd. & Corporate Office: Bharti Crescent, 1, Nelson Mandela Road, Vasant Kunj, Phase II, New Delhi 110 070 T.: +91-11-4166 6100, F: +91-11-4166 6137 Bharti and Reliance Jio announce agreement for international data connectivity • Reliance Jio to utilise dedicated fiber pair on Bharti’s i2i submarine cable that connects India and Singapore • State-of-the-art i2i cable system will provide Reliance Jio direct access and ultra fast connectivity to major hubs across Asia Pacific New Delhi, April 23, 2013 – Bharti Airtel Limited (“Bharti”), a leading global telecom services provider with operation s in 20 countries across Asia and Africa, and Reliance Jio Infocomm Limited (“Reliance Jio”) today announced that they have signed an Indefeasible Right to Use (IRU) Agreement, under which Bharti will provide Reliance Jio data capacity on its i2i submarine cable. i2i connects India to Singapore and is wholly owned by B harti. The state -of-the-art cable consists of eight fiber pairs using DWDM (Dense Wavelength Division Multiplexing) , capable of supporting multiple terabits of capacity per fiber pair.