Pentecostal Experience and Hermeneutics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BC's Faith-Based Postsecondary Institutions

Made In B.C. – Volume II A History of Postsecondary Education in British Columbia B.C.’s Faith-Based Postsecondary Institutions Bob Cowin Douglas College April 2009 The little paper that keeps growing I had a great deal of fun in 2007 using some of my professional development time to assemble a short history of public postsecondary education in British Columbia. My colleagues’ interest in the topic was greater than I had anticipated, encouraging me to write a more comprehensive report than I had planned. Interest was such that I found myself leading a small session in the autumn of 2008 for the BC Council of Post Secondary Library Directors, a group that I enjoyed meeting. A few days after the session, the director from Trinity Western University, Ted Goshulak, sent me a couple of books about TWU. I was pleased to receive them because I already suspected that another faith-based institution, Regent College in Vancouver, was perhaps BC’s most remarkable postsecondary success. Would Trinity Western’s story be equally fascinating? The short answer was yes. Now I was hooked. I wanted to know the stories of the other faith-based institutions, how they developed and where they fit in the province’s current postsecondary landscape. In the ensuing months, I poked around as time permitted on websites, searched library databases and catalogues, spoke with people, and circulated drafts for review. A surprisingly rich set of historical information was available. I have drawn heavily on this documentation, summarizing it to focus on organizations rather than on people in leadership roles. -

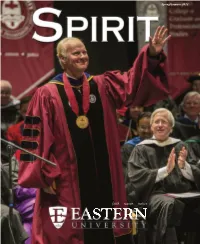

Faith Reason Justice SPIRIT

Spring/Summer 2014 faith reason justice SPIRIT The Magazine of EASTERN UNIVERSITY Spring/Summer 2014 Spirit is published by the Communications Office Eastern University 1300 Eagle Road St. Davids, PA 19087 610.341.5930 — Linda A. Olson ’96 M.Ed. Executive Director Patti Singleton Inside This Issue Art Director Staff Photographer Jason James THE INAUGURATION AND INSTALLATION Graphic Designer and Public Relations Assistant OF ROBERT G. DUFFETT......................................................1 Elyse Garner ’13 Writer/Social Media Coordinator ACADEMICS...................................................................................6 — FAITH AND PRACTICE..............................................................17 Article suggestions should be sent to: Linda A. Olson 610.341.5930 COMMUNITY NEWS..................................................................21 e-mail: [email protected] Alumni news should be sent to: 1.800.600.8057 ATHLETIC NEWS........................................................................25 www.alumni.eastern.edu ALUMNI NEWS MISSION STATEMENT Alumna of the Year ..............................................................................26 Spirit supports the mission of Eastern University to provide a Christian higher Young Alumnus of the Year..................................................................27 education for those who will make a difference in the world through careers and Class Notes ..........................................................................................28 personal -

Summit Pacific College Catalogue 2018-19

76626 Summit Pacific Cover.indd 1 2016-03-24 10:33 AM This page is intentionally blank. CONTENTS Address, Affiliation and Mission 1 Memberships and Accreditation 1-2 Location and Travel 2 A Word from the President 3 Academic Calendar 4 Faculty, Administrators, Staff 5-9 Academic Programs 11-37 Description of Courses 39-56 Admission 57 Cost 58-59 Academic Procedures 59-62 Memberships and Recognitions 63 Statement of Faith 63 Statement of Philosophy 63-64 Mission, Values and Outcomes 64 Assessment 64 Statistics 65 Logo, Crest and Colours 66 History of Summit 66-67 Campus Facilities 67-68 Student Life and Community 69 Spiritual Life 69 Student Services 69-71 College Standards and Regulations 71 Awards, Bursaries and Scholarships 71 Correspondence Directory 72 Contact Directory 72 This page is intentionally blank. 2018-2019 CATALOGUE Memberships and Accreditation Summit Pacific College is accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of the Association for Biblical Higher Education (ABHE) to grant certificates and degrees at the Associate and Baccalaureate levels. 35235 STRAITON ROAD ABBOTSFORD, B.C. V2S 7Z1 POSTAL ADDRESS: BOX 1700, ABBOTSFORD, B.C. V2S 7E7 PHONE: (604) 853-7491 TOLL FREE: 1-800-976-8388 FAX: (604) 853-8951 EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.summitpacific.ca ASSOCIATION FOR BIBLICAL HIGHER EDUCATION For admission and registration information call 1- 5850 TG Lee Blvd., Suite 130 Orlando, FL 32822 PHONE: (407) 207-0808 800-976-8388 FAX: (407) 207-0840 EMAIL: [email protected] URL: www.abhe.org AFFILIATED WITH TRINITY WESTERN UNIVERSITY 7600 Glover Road, Langley, B.C., Canada V2Y 1Y1 SPC MISSION STATEMENT Summit Pacific College exists to educate, equip and enrich Christians for Spirit-empowered ministry in the church and in the world. -

SCHOOL of GRADUATE STUDIES “Developing Christian Leaders for Church and Society”

76626 Summit Pacific Cover.indd 1 2016-03-24 10:33 AM SUMMIT PACIFIC COLLEGE SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES “Developing Christian Leaders for Church and Society” CATALOGUE AND HANDBOOK Fall 2017 1 2 CATALOGUE AND HANDBOOK Fall 2017 3 4 CONTENTS Address, Affiliation, Memberships and Accreditation 6 A Word from the President 8 A Word from the Dean 9 Mission, Board of Governors and History 10 Teaching and Support Staff 11 Campus Facilities 14 Student Life & Community and Spiritual Life 15 Graduate Program Outline and Degree Completion 16 Academic Calendar 2016-2017 16 Student Card and Keeping Connected 17 Admission and Financial Information 18 Academic Information 20 Aim of the study program 20 Mode of Study 20 Course Descriptions 22 General Objectives and Work Load 24 General Grading Rubric 26 Study Support 27 Written Assignments/Research Papers 28 Late Submission 29 From Audit to Credit and Dropping the Class 29 Re-Sits 29 Student Feedback 29 Academic Integrity 29 Academic Progress 31 Equity of Access 31 Detailed Grading Criteria for Essays/Theses 32 Appendix #1: Footnotes & Bibliography 34 Appendix #2: Cover Page 36 Appendix #3: Table of Contents 37 5 SUMMIT PACIFIC COLLEGE 35235 STRAITON ROAD ABBOTSFORD, B.C. POSTAL ADDRESS: BOX 1700, ABBOTSFORD, B.C. V2S 7E7 General Inquires: (604) 853-7491 Toll-Free: 1-800-976-8388 Fax: (604) 853-8951 Dean of Graduate Studies: (604) 851-7217 Graduate Studies Email: [email protected] Website: www.summitpacific.ca AFFILIATED WITH TRINITY WESTERN UNIVERSITY 7600 Glover Road, Langley, B.C., Canada V2Y 1Y1 Memberships and Accreditation Summit Pacific College is accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of the Association for Biblical Higher Education (ABHE) to grant degrees at the Associate and Bachelors levels. -

A Dialogical Approach to Pentecostal Pneumatology by Allison S

A Dialogical Approach to Pentecostal Pneumatology by Allison S. MacGregor Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Theology) Acadia University Fall Convocation 2011 © by Allison S. MacGregor, 2011 This thesis by ALLISON S. MACGREGOR was defended successfully in an oral examination on DATE OF DEFENCE. The examining committee for the thesis was: ________________________ Dr. Bruce Fawcett, Chair ________________________ Dr. Van Johnson ________________________ Dr. Robert Wilson ________________________ Dr. William Brackney, Supervisor ________________________ Dr. Craig Evans, Director of MA program, Acadia Divinity College ________________________ Dr. Harry Gardner, President, Acadia Divinity College This thesis is accepted in its present form by the Division of Research and Graduate Studies as satisfying the thesis requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Theology). …………………………………………. ii I, ALLISON S. MACGREGOR, grant permission to the University Librarian at Acadia University to reproduce, loan or distribute copies of my thesis in microform, paper or electronic formats on a non-profit basis. I, however, retain the copyright in my thesis. ______________________________ Author ______________________________ Supervisor ______________________________ Date iii To My Children Gifts from the Lord iv CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................ vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................... -

MARTIN WILLIAM MITTELSTADT PUBLICATIONS Updated May 2021

MARTIN WILLIAM MITTELSTADT PUBLICATIONS Updated May 2021 Professor of New Testament @ Evangel University (2000- ) Email: [email protected] Faculty Page: https://www.evangel.edu/faculty/martin-mittelstadt/ Academia.edu: https://evangel.academia.edu/MartinMittelstadt Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/author/mittelstadtm BOOKS/MONOGRAPHS • CANADIAN PENTECOSTAL READER: THE FIRST GENERATION OF PENTECOSTAL VOICES IN CANADA (1907-1925). Co-edited with Caleb Howard Courtney. Cleveland, TN: CPT Press, 2021. • MENNOCOSTALS: MENNONITE AND PENTECOSTAL STORIES OF CONVERGENCE. Co-edited with Brian K. Pipkin. Pentecostals, Peace-Making and Social Justice Series. Eugene, OR: Pickwick (Wipf & Stock), 2020. • READING SCRIPTURE IN THE PENTECOSTAL TRADITION: A RECEPTION HISTORY. Co-edited with Rick Wadholm and Daniel Isgrigg. Cleveland, TN: CPT Press, 2021. • WHAT’S SO LIBERAL ABOUT THE LIBERAL ARTS? ESSAYS IN HONOR OF JAMES AND TWILA EDWARDS: EXEMPLARS OF AN INTEGRATIVE, MULTI- DISCIPLINARY APPROACH TO LIBERAL ARTS EDUCATION. Co-Edited with Paul W. Lewis. Frameworks: Interdisciplinary Studies for Faith and Learning 1. Eugene, OR: Pickwick (Wipf & Stock), 2016. • THE THEOLOGY OF AMOS YONG AND THE NEW FACE OF PENTECOSTAL SCHOLARSHIP: PASSION FOR THE SPIRIT. Co-edited with Wolfgang Vondey. Global Pentecostal and Charismatic Studies Series 14. Leiden: Brill, 2013. Page 2 of 21 • READING LUKE-ACTS IN THE PENTECOSTAL TRADITION. Cleveland, TN: CPT Press, 2010. - Received "Book of the Year" Award from the Foundation for Pentecostal Scholarship (http://www.tffps.org) in 2011. - Translated into Chinese by Robert Chi Kong Yeung. • FORGIVENESS, RECONCILIATION, AND RESTORATION: MULTIDISCIPLINARY STUDIES FROM A PENTECOSTAL PERSPECTIVE. Co-edited with Geoffrey Sutton. Pentecostals, Peacemaking and Social Justice Series 3. Eugene, OR: Pickwick (Wipf & Stock), 2010. -

HOM/TH6/702 – the Holy Spirit & The

HOM/TH6/702 – The Holy Spirit & the Renewal of the Church Jason Byassee Spring 2020 Description: The descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, transforming bewildered disciples into apostles, is the birth of the church. Yet the doctrine of the Spirit has often been neglected in western theology. The rise of Pentecostalism has rejected this rejection, so that now it is difficult to do theology without sustained attention to pneumatology. And yet even in this Pentecostal revival of attention to the Spirit, actual churches are often neglected. The living, breathing, temple of the Holy Spirit is almost a distraction in constructing doctrine. Let’s change that, shall we?! This course will attend to the history of the dogma of the Spirit in the ancient church, examining Basil, Gregory Nazianzen, and Augustine. We will then turn to renewed 20th and 21st century attention to the Spirit in dogmatic theology. We will read Amos Yong together on the rise of Pentecostalism. Then we will attend to local churches in Vancouver and see what is to be learned about the Spirit by talking to our neighbours, perhaps especially those most challenging to our presuppositions. The course is part dogmatics, part journalism, part reimagining our own ministries and theologies in light of the Spirit who confuses language, teaches speech, melts division into love, and prays that the kingdom would come soon. Competencies 1-to articulate the stakes and the decisions of the ancient church on the doctrine of the Holy Spirit 2-to narrate well the 20th and 21st century revival of the Spirit in doctrine and practice, especially Pentecostalism’s role in that revival 3-to attend to living, breathing churches in our midst now 4-to articulate and defend a pneumatology for the sake of one’s own doctrine and practice Assignments 1-Present in class on some key pneumatological passage in the bible and how this became part of the patristic pneumatology of the ancient church. -

List of Recognized Institutions Updated: January 2017

Knowledge First Financial ‐ List of Recognized Institutions Updated: January 2017 To search this list of recognized institutions use <CTRL> F and type in some, or all, of the school name. Or click on the letter to navigate down this list: ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 1ST NATIONS TECH INST-LOYALIST COLL Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory ON Canada 5TH WHEEL TRAINING INSTITUTE, NEW LISKEARD NEW LISKEARD ON Canada A1 GLOBAL COLLEGE OF HEALTH BUSINESS AND TECHNOLOG MISSISSAUGA ON Canada AALBORG UNIVERSITETSCENTER Aalborg Foreign Prov Denmark AARHUS UNIV. Aarhus C Foreign Prov Denmark AB SHETTY MEMORIAL INSTITUTE OF DENTAL SCIENCE KARNATAKA Foreign Prov India ABERYSTWYTH UNIVERSITY Aberystwyth Unknown Unknown ABILENE CHRISTIAN UNIV. Abilene Texas United States ABMT COLLEGE OF CANADA BRAMPTON ON Canada ABRAHAM BALDWIN AGRICULTURAL COLLEGE Tifton Georgia United States ABS Machining Inc. Mississauga ON Canada ACADEMIE CENTENNALE, CEGEP MONTRÉAL QC Canada ACADEMIE CHARPENTIER PARIS Paris Foreign Prov France ACADEMIE CONCEPT COIFFURE BEAUTE Repentigny QC Canada ACADEMIE D'AMIENS Amiens Foreign Prov France ACADEMIE DE COIFFURE RENEE DUVAL Longueuil QC Canada ACADEMIE DE ENTREPRENEURSHIP QUEBECOIS St Hubert QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASS. ET D ORTOTHERAPIE Gatineau (Hull Sector) QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASSAGE ET D ORTHOTHERAPIE GATINEAU QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASSAGE SCIENTIFIQUE DRUMMONDVILLE Drummondville QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASSAGE SCIENTIFIQUE LANAUDIERE Terrebonne QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASSAGE SCIENTIFIQUE QUEBEC Quebec QC Canada ACADEMIE DE SECURITE PROFESSIONNELLE INC LONGUEUIL QC Canada Knowledge First Financial ‐ List of Recognized Institutions Updated: January 2017 To search this list of recognized institutions use <CTRL> F and type in some, or all, of the school name. Or click on the letter to navigate down this list: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z ACADEMIE DECTRO INTERNATIONALE Quebec QC Canada Académie des Arts et du Design MONTRÉAL QC Canada ACADEMIE DES POMPIERS MIRABEL QC Canada Académie Énergie Santé Ste-Thérèse QC Canada Académie G.S.I. -

Global University Undergraduate School of Bible and Theology Catalog

2018 GLOBAL UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE SCHOOL OF BIBLE AND THEOLOGY CATALOG 1211 South Glenstone Avenue • Springfield, Missouri 65804-0315 USA Telephone: 800.443.1083 • 417.862.9533 • Fax 417.862.0863 E-mail: [email protected] • Internet: www.globaluniversity.edu © 2018 Global University All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS A Letter from the President ........................................ 4 Student Advisement ....................................................23 A Letter from the Provost ............................................ 5 Student Number and Student Card ...............................23 Academic Good Standing .............................................24 General Information ................................................... 6 Foreword ...................................................................... 6 Credit System ..............................................................24 History ......................................................................... 6 Transfer of Global University Credit ...............................25 Mission of Global University .......................................... 6 Global University Transcripts ........................................25 Doctrinal Statement ...................................................... 6 Capstone Requirements ...............................................25 Notice of Non-Discriminatory Policy ................................7 Graduation Requirements ........................................... 26 Global University International Headquarters -

"Pilgrimage Into Pentecost: the Pneumatological Legacy of Howard

Oral Roberts University Digital Showcase College of Science and Engineering Faculty College of Science and Engineering Research and Scholarship 3-2008 "Pilgrimage Into Pentecost: The neumP atological Legacy of Howard M. Ervin" Daniel D. Isgrigg Oral Roberts University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalshowcase.oru.edu/cose_pub Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Catholic Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the New Religious Movements Commons Recommended Citation Daniel D. Isgrigg, "Pilgrimage Into Pentecost: The neP umatological Legacy of Howard M. Ervin." A paper presented at the 37th Annual Meeting of the Society for Pentecostal Studies (Durham, NC: Mar 13-15, 2008). This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Science and Engineering at Digital Showcase. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Science and Engineering Faculty Research and Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Showcase. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Pilgrimage Into Pentecost: The Pneumatological Legacy of Howard M. Ervin” 1 Ecumenical Studies Group Daniel D. Isgrigg Christian Chapel (Tulsa, OK) Presented at the 37th Annual Meeting of the Society for Pentecostal Studies Introduction Howard M. Ervin, a Baptist and Pentecostal scholar, paved the way for other scholars to defend the Pentecostal faith in the academic world. During the last half of the twentieth century, charismatics, evangelicals and Pentecostals scholars have debated the nature and function of Spirit baptism. Early in the debate, Howard Ervin offered a view of Spirit baptism that centered on Luke’s unique pneumatology in Luke-Acts and meaning of the term “filled with the Spirit.” Ervin’s work, These Are Not Drunken as Ye Suppose (1968), was one of the first books to enter the scholarly debate from the Pentecostal position. -

Summit Pacific College Distance Education Catalogue

DISTANCE EDUCATION CATALOGUE 2021 - 2022 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMIT PACIFIC COLLEGE 2 MEMBERSHIPS AND ACCREDITATION 2 ADMINISTRATORS AND FACULTY 4 DISTANCE EDUCATION DIRECTOR 6 CONTACT INFORMATION 6 DISTANCE EDUCATION UPDATE 2021-22 7 ONLINE COURSE DELIVERY 2021-22 7 PROGRAMS OF STUDY 8 QUICK FACTS 9 ROMER CERTIFICATE 10 CAMPUS MISSIONARY IN TRAINING (CMIT) 11 CHILD AND FAMILY MINISTRY CERTIFICATE 12 YOUTH MINISTRY CERTIFICATE 13 YOUTH MINISTRY ROMER CERTIFICATE 14 CHURCH MINISTRIES CERTIFICATE 15 PASTORAL MINISTRIES DIPLOMA 16 BACHELOR OF THEOLOGY DEGREE (B.Th.) 18 DISTANCE EDUCATION OPTIONS FOR CHURCHES 20 COURSE DESCRIPTIONS 21 FINANCIAL INFORMATION 29 TUITION AND RELATED FEES 29 SHIPPING AND HANDLING 31 INCOME TAX RECEIPTS 31 PROGRAM SUMMARY FOR BUDGETING 31 ACADEMIC INFORMATION 32 ADMISSION REQUIREMENTS 32 CASUAL (PART-TIME) STUDIES 33 IS DISTANCE EDUCATION FOR YOU? 34 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS 35 APPLICATIONS 36 TRANSFER 37 EXAMS 38 ASSIGNMENTS 39 SUMMIT STYLE GUIDE 39 STUDENT ASSIGNMENT ASSESSMENT RUBRIC 39 GRADING SYSTEM INFORMATION 40 COURSE INTEGRITY AND ASSESSMENT 40 REFERENCE AND STUDY SUPPLIES 41 STUDENT MINISTRY 42 FULFILLING PAOC CREDENTIAL REQUIREMENTS 43 POLICY TO RESOLVE STUDENT DISPUTES 45 DISMISSAL POLICY AND PROCEDURES 45 GENERAL INFORMATION 46 STATEMENT OF PHILOSOPHY 46 A BRIEF HISTORY OF SUMMIT PACIFIC COLLEGE DISTANCE EDUCATION 52 STATEMENT OF FAITH 53 INDEX 54 Summit Pacific College is accredited by the Association for Biblical Higher Education Commission on Accreditation to grant certificates and theological degrees at the Associate, Baccalaureate, and Master’s levels. Any queries about Summit's status may be directed to: Association of Biblical Higher Education 5850 TG Lee Blvd., Suite 130, Orlando, FL 32822 PHONE: 407-207-0808 FAX: 407-207-0840 EMAIL: [email protected] Web: www.abhe.org Summit Pacific College is a member of the Council for Higher Education Accreditation. -

THE ROLE of EXPERIENCE in the INTERPRETATION of MIRACLE NARRATIVES in LUCAN LITERATURE Biblical Studies Robert R

Robert R. Wadholm, “Interpretation of Miracle Narratives” THE ROLE OF EXPERIENCE IN THE INTERPRETATION OF MIRACLE NARRATIVES IN LUCAN LITERATURE Biblical Studies Robert R. Wadholm, Trinity Theological Seminary Presented at the 36th Annual Meeting of the Society for Pentecostal Studies Various rationalists of the past and present have viewed biblical and modern-day miracles as propaganda, superstition, and foolish contrivances of a premodern worldview.1 The Gospels and Acts have been considered historically unreliable because of their numerous accounts of miracles.2 A number of conservative evangelical theologians and scholars have similarly voiced their disbelief in modern miracles, signs, and wonders.3 However, a growing number of evangelicals are becoming aware of the importance of modern miraculous experiences in evangelism.4 An increasing openness to modern experiences of miracles has led to a reassessment of the role of experience in interpreting the Bible. A holistic hermeneutic is being developed that more fully appreciates the role of experience in the interpretive process. Traditional Christianity has often emphasized the importance of salvific experience in hermeneutics, while ignoring or denying the role of miraculous experiences. The experiential miracle narratives of Luke-Acts have become a sort of key to assessing the role of experience in biblical interpretation. Developing a Holistic Hermeneutic Advocates of modern miracles have developed a holistic hermeneutic which articulates a four-principle method of biblical interpretation: presuppositions, context (exegesis and explication), organization (biblical and systematic theological analysis), and application.5 When interpreting the miracle narratives of Luke-Acts, each of these four principles requires some sort of dialogue with experiences (both modern and ancient).