Batteries for Electric Cars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Platinum Metals Review

PLATINUM METALS REVIEW A quarterly survey of research on the platinum metals and of developments in their application in industry VOL. 10 APRIL 1966 NO. 2 Contents Recent Advances in Industrial Platinum Resistance Thermometry 42 Petrochemicals by Platinum Reforming 47 Prevention of Corrosion in Paper Making Machines 48 Expansion in Platinum Production 52 Platinum-wound Furnaces in the Manufacture of Semiconductors 53 The Wetting of Platinum and its Alloys by Glass 54 Electrodeposition of Iridium 59 The Reaction between Hydrogen and Oxygen on Platinum 60 Catalysis of Olefin-to-Olefin Addition 65 Abstracts 66 New Patents 73 Communications should be addressed to The Editor, Platinum Metals Review Johnson, Matthey & Co Limited, Hatton Garden, London ECI Recent Advances in Industrial Platinum Resistance Thermometry By J. S. Johnston, B.s~.,A.R.C.S. Rosemount Engineering Company Limited, Bognor Regis The modern platinum resistance thermometer provides the most accurate and versatile method of industrial temperature measurement and control. This article gives details of a new design of platinum resistance thermo- meter element of small dimensions and good stability. It also describes a range of complete thermometers based on these elements together with a resistance-bridge system used for signal conditioning when the thermo- meters are used in data-logging or computer controlled systems. Two principal factors have contributed to a thermometer confers the advantages of better recent large increase in the use of platinum reproducibility and larger output signal resistance thermometers in industry. On the coupled with the ability to scale the output one hand new techniques of manufxture to fit the requirements of the instrumentation. -

Jcb Warranty Guide

JCB WARRANTY GUIDE ENGLISH - 9814/0930 - ISSUE 2 - OCT 2012 Copyright © 2004 JCB SERVICE. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any other means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without prior permission from JCB SERVICE. A4-11 - Printed In England Notes 0 9814/0930 0 Contents Page No. Warranty Guide 2012 1. Introduction ................................................................................................1 2. Warranty Philosophy .................................................................................3 3. Certificate of Warranty ...............................................................................5 4. Customers Obligations ..............................................................................9 5. Dealer’s Obligations ................................................................................ 11 6. JCB's Obligations ....................................................................................15 7. Non Warrantable Items ............................................................................23 8. Goodwill ...................................................................................................27 9. Extended Warranty ..................................................................................29 10. Warranty Parts Returns .........................................................................31 11. Warranty Review ....................................................................................35 -

Construction & Industrial Equipment

State Term Contract No. 22101000-15-1; Construction & Industrial Equipment Section 2.3.3 Revised: November 6, 2015 NOTE TO USERS: To fully use this document, you must maintain an active internet connection (high-speed recommended) and have the latest version of the Adobe Reader installed. If you need the free Adobe Reader, go to http://www.adobe.com/, click on the "Get Adobe Reader" icon, and follow the software's directions for installation and use. Printing this document will not automatically print any linked documents. To print any of the linked documents, you must individually open and print the linked documents. VIEWING NOTE: Due to the width and height of this document and the available screen space of your monitor, you may need to scroll across and up-and-down this document to view all available columns and rows. To scroll across this document, you can use the scroll bar in the bottom right of this window; to scroll up-and-down this document, you can use the scroll bar at the right of this window. KEY NOTE: For additional information related to this document, please see the Key toward the bottom of this document. INSTRUCTIONS: Please review the Contract, Contact Information for Instructions and Frequently Asked Questions on the DMS Website. Please click on the hyperlinks below for the MSRP pages or Contractor's information. *** IMPORTANT Please Note: *** Some models on the MSRP pages may not be eligible for purchase on this contract. Please refer to the group and specs. defined within the contract. If the Manufacturer or Brand says to contact the Contract Admin these MSRP pages are available upon request. -

September 2020

TB Saracen UK Alpha Fund September 2020 Fund Overview FOR PROFESSIONAL INVESTORS ONLY • Objective: to achieve a higher rate of return than the MSCI UK All Cap Index by investing in a portfolio of primarily UK equity securities with the potential for long Retail investors should consult their term growth. financial advisers • The portfolio has a bias towards small and medium sized companies and a high active share compared to the benchmark. FUND DETAILS th (as at 30 September 2020) • The fund has significant capacity and liquidity at a competitive annual charge. • The Fund has, since launch in March 1999, outperformed its benchmark in 17 out Fund size: £10.3m of 21 years and in 8 out of the last 10 calendar years. Launch date: 05/03/99 • A concentrated portfolio of 25-35 holdings, with a focus on capital growth, backed by the Saracen research process. No. of holdings: 33 Active share: 93% Source: Bloomberg Performance Chart* TB Saracen UK Alpha Fund B Acc Denomination: GBP 5 Year Performance (%) MSCI UK All Cap Index (TR) Valuation point: 12 noon 170 160 Fund prices: A Accumulation: 395.73p 150 B Accumulation: 651.65p 140 Policy is not to charge a dilution levy except in exceptional circumstances. 130 120 ACD: 110 T. Bailey Fund Services Limited 100 90 80 Scott McKenzie David Clark Fund Manager Fund Manager 09/15 03/16 09/16 03/17 09/17 03/18 09/18 03/19 09/19 03/20 09/20 *Source: Bloomberg, as at 30th September 2020 Total Return, Bid to Bid, GBP terms. -

JCB Backhoe Loader Application

BACKHOE LOADER A Product of Hard Work All the attachments you need ATTACHMENT bucket Loader shovels quickhitch Rehandling crane hook Snow blade Waste skip* 6-in-1 shovel Dozer blade* Concrete skip Road sweeper Side-tip shovel Fork-mounted INDUSTRY Industrial forks High-tip shovel* When you buy a JCB backhoe loader, you buy the very General purpose best there is, as more than 65 years of continuous Building 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 product leadership testify. Now, in this special brochure, we show you a whole Highways 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 range of thought-provoking equipment ideas, designed to help you achieve even higher productivity, and the most Local Authorities 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 profitable return on your investment. Most of the attachments are equally suitable for earlier, as well as Gas 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 new, JCB machines. Your local JCB Distributor will be pleased to supply full details. Electricity & Telecom 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Use this quick-reference chart to find attachments of particular interest to you. Water 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Agriculture 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Land Drainage 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Forestry 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Railways 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Page 6 6 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 – – * Not all attachments are supplied and supported by JCB. -

Yright LASER Copyright LA Copyright LASER Copyright

Copyright Copyright LASER Copyright LASER Copyright LASER Copyright Copyright LASER Copyright Copyright LASER LASER Copyright Copyright LASER LASER Copyright Copyright LASER Incorrect or out of phase engine timing LASER Incorrect or out of phase engine timing can result in damage to the valves. can result in damage to the valves. Copyright The Tool Connection cannot be held Copyright The Tool Connection cannot be held Copyrightresponsible for any damage caused by responsible for any damageLASER caused by using these tools in anyway. LASER using these tools in anyway. Copyright Safety Precautions – Please read Copyright Safety Precautions – Please read Copyright LASER • Disconnect the battery earth leads (check PartLASER No. 1868 • Disconnect the battery earth leads (check Part No. 1868 LASER radio code is available) radio code is available) Copyright • Remove spark or glow plugs to make the Copyright• Remove spark or glow plugs to make the engine turn easierCopyright Diesel engine turn easier LASER Diesel • Do not use cleaning fluids on belts, sprockets LASER • Do not use cleaning fluids on belts, sprockets LASERor rollers Timing Kit or rollers Timing KitCopyright • Always make a note of the route of the Copyright• Always make a note of the route of the auxiliary drive belt before removalCopyright For Audi | Seat auxiliary drive belt before removal LASERFor Audi | Seat • Turn the engine in the normal direction LASER • Turn the engine in the normal direction LASER(clockwise unless stated otherwise) Volvo | Volkswagen (clockwise unless -

Presentation to Analysts / Investors Johnson Matthey in China

Presentation to Analysts / Investors Johnson Matthey in China London Stock Exchange 27th / 28th January 2010 Cautionary Statement This presentation contains forward looking statements that are subject to risk factors associated with, amongst other things, the economic and business circumstances occurring from time to time in the countries and sectors in which Johnson Matthey operates. It is believed that the expectations reflected in these statements are reasonable but they may be affected by a wide range of variables which could cause actual results to differ materially from those currently anticipated. Overview and Trading Update Neil Carson Chief Executive JM Executive Board • Neil Carson - Chief Executive • Robert MacLeod - Group Finance Director • Larry Pentz - Executive Director, Environmental Technologies • Bill Sandford - Executive Director, Precious Metal Products 4 Other Senior Management • John Walker Division Director, Emission Control Technologies • Neil Whitley Division Director, Process Technologies • Nick Garner Division Director, Fine Chemicals • Geoff Otterman Division Director, Catalysts, Chemicals and Refining • Linky Lai General Manager, Emission Control Technologies, China • Henry Liu Commercial Director, Emission Control Technologies, China • Peng Zhang Sales Director, Power Plant Industries, China • Wolfgang Schuettenhelm Director, Worldwide Power Plant Industries • Andrew Wright Managing Director, Syngas and Gas to Products • David Tomlinson President, Davy Process Technology • Vikram Singh Country Head (AMOG) -

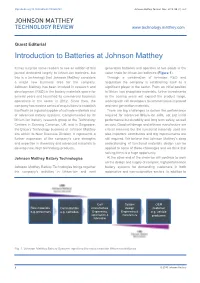

Introduction to Batteries at Johnson Matthey

http://dx.doi.org/10.1595/205651315X686723 Johnson Matthey Technol. Rev., 2015, 59, (1), 2–3 JOHNSON MATTHEY TECHNOLOGY REVIEW www.technology.matthey.com Guest Editorial Introduction to Batteries at Johnson Matthey It may surprise some readers to see an edition of this generation batteries and operates at two points in the journal dedicated largely to lithium-ion batteries, but value chain for lithium-ion batteries (Figure 1). this is a technology that Johnson Matthey considers Through a combination of in-house R&D and a major new business area for the company. acquisition the company is establishing itself as a Johnson Matthey has been involved in research and signifi cant player in the sector. From an initial position development (R&D) in the battery materials space for in lithium iron phosphate materials, further investments several years and launched its commercial business in the coming years will expand the product range, operations in the sector in 2012. Since then, the working with cell developers to commercialise improved company has made a series of acquisitions to establish and next generation materials. itself both as a global supplier of cathode materials and There are big challenges to deliver the performance of advanced battery systems. Complemented by its required for advanced lithium-ion cells, not just initial lithium-ion battery research group at the Technology performance but durability and long term safety, as well Centres in Sonning Common, UK, and in Singapore, as cost. Good cell design and effi cient manufacture are the Battery Technology business of Johnson Matthey critical elements but the functional materials used are sits within its New Business Division. -

Paperwork Included: Service History and Registration Book

Scammell 20 MU GDC Tractor Unit, NAX272 + | Paperwork Included: Service History and Registration Book 14500 O & K RH6 Excavator + | Paperwork Included: Service History, Operators Manual and Registration Book 11500 Caterpillar D6 B Bulldozer + | Paperwork Included: Service History, Service Manual, Spares Catalogue and Delivery 8900 Note Ruston Bucyrus 22 RB Dragline, YW0729J + Ruston & Hornsby 6YDA Air Cooled Engine, Bucket | Paperwork 8800 Included: Service History, Operators Manual, Spares Catalogue and Registration Book International 175 Series C Traxcavator + Rubery Owen 4 in 1 Bucket | Supplied By Savilles Of Cardiff - Paperwork 7900 Included: Service History, Operators Manual and Spares Catalogue Hy-Mac 370 Backhoe Loader, GHW662N + | Paperwork Included: Service History, Operators Manual, Spares 6300 Catalogue and Registration Book Hy-Mac HM 590 C Excavator, PWO489M + | Paperwork Included: Service History, Operators Manual, Spares 5500 Catalogue and Registration Book Ruston Bucyrus RB 19 Dragline + Bucket | Paperwork Included: Service History, Operators Manual, Spares Catalogue 5500 and Registration Book Ruston Bucyrus 10 RB Dragline Excavator, UAX355 + Bucket | Paperwork Included: Service History, Operators 4800 Manual, Spares Catalogue and Registration Book Caterpillar 951 Traxcavator And 5 Tine Ripper, KAX526D + | Paperwork Included: Service History, Operators Manual, 4100 Registration Book and Supplier Delivery Report Stating Supplied By Bowmaker Plant Cardiff International Hough H 30 B Payloader Loading Shovel + Ripper, PWO218F -

Batteries and Storage Charging the Green Transition: Green Transition Scoreboard® 2015 Fall Update

Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Batteries and Storage in a Systems Approach to Energy ................................................... 2 State of Technology 2015 ............................................................................................... 3 Emerging Opportunities .................................................................................................. 4 Reforming of the Financial System ................................................................................. 5 Changing Roles of Electric Utilities and Grids ................................................................ 6 New Materials Search ..................................................................................................... 7 Exploring the Numbers........................................................................................................ 8 Notes ................................................................................................................................. 11 Batteries and Storage Charging the Green Transition: Green Transition Scoreboard® 2015 Fall Update Authors: Hazel Henderson, Rosalinda Sanquiche, Timothy Jack Nash Reference suggestion: Henderson, H., Sanquiche, R. and Nash, T. “Batteries and Storage Charging the Green Transition: Green Transition Scoreboard® 2015 Fall Update”, Ethical Markets Media, September 2015. © 2015 Ethical Markets Media, LLC This update does not contain -

AROUND the INDUSTRY Currently Under Construction in the Tahoe-Reno Industrial Center (TRIC) in Nevada

Volume 51 Number 11 ISSN: 001-8627 November 2015 in Shanghai and Palo Alto. And as a further measure to advance Li-ion battery research, Bosch has established the Lithium Energy and Power GmbH & Co. KG joint venture with GS Yuasa and the Mitsubishi Corp. “The more lithium ions you have in a battery, the more electrons – and thus the more energy – you can store in the same space,” explains Ochs. Aqua Metals Closes $10 Million for Recycling Center Aqua Metals Inc., which is commercializing a non- polluting electrochemical lead recycling technology called AquaRefining™, has a $10 million loan from Green Bank in conjunction with a 90% loan guarantee from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Rural In the Bosch center for research and advanced engineering, Dr Development Agency. The loan will provide non-dilutive Throsten Ochs works on the batteries of the future. See story below. capital to finance the growth of Aqua Metals and enhance the development of the company’s first AquaRefinery AROUND THE INDUSTRY currently under construction in the Tahoe-Reno Industrial Center (TRIC) in Nevada. The company intends to apply Bosch’s Renningen Research Campus Inauguration the proceeds to expand its lead recycling capacity. Dr. Thorsten Ochs, head of battery technology R&D “Our credit enhancement tool is designed to lend the at the newly inaugurated Bosch research campus in support needed to bring advanced technology businesses Renningen, explains what will be necessary for progress in into America’s rural areas, creating jobs and progress,” battery technology: “To achieve widespread acceptance of says Sarah Adler, Nevada State Director of USDA Rural electromobility, mid-sized vehicles need to have 50kWhrs Development. -

Safety Recall Code: 69Q9 REVISION

Safety Recall Code: 69Q9 REVISION Subject TAKATA SDI Driver Frontal Airbag Inflator Release Date August 31, 2018 Revision Summary • Added repair availability for vehicles with Criteria T3 • When replacing the airbag assembly for vehicles with Criteria T3, the airbag control module will be coded and parameterized. Instructions specific to this process have been added to work procedure. Affected Vehicles U.S.A. & CANADA: Certain 2007-2014 MY Volkswagen vehicles equipped with a Takata SDI driver frontal airbag Check Campaigns/Actions screen in Elsa on the day of repair to verify that a VIN qualifies for repair under this action. Elsa is the only valid campaign inquiry & verification source. Campaign status must show “open.” If Elsa shows other open action(s), inform your customer so that the work can also be completed at the same time the vehicle is in the workshop for this campaign. Problem Description The driver airbag may explode in a crash with airbag deployment. Sharp metal fragments can hit people and cause serious injury or death. Corrective Action Replace the driver frontal airbag inflator with a newly manufactured version. This repair is the final remedy. Parts Information Parts will be allocated weekly. Please email [email protected] with Vin if you do not have the proper part(s) in stock. Criteria T2 Code On June 29, 2018, criteria T2 vehicles were listed on the Inventory Vehicle Open Campaign Visibility Action report under My Dealership Reports (found on www.vwhub.com & OMD Web). A list was not posted for dealers who did not have any affected vehicles. On June 29, 2018, this campaign code showed open on criteria T2 vehicles in Elsa.