(Insects, Blattodea) in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest Vitor Dias Tarli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Aspects About Supella Longipalpa (Blattaria: Blattellidae)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2016; 6(12): 1065–1075 1065 HOSTED BY Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/apjtb Review article http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apjtb.2016.08.017 New aspects about Supella longipalpa (Blattaria: Blattellidae) Hassan Nasirian* Department of Medical Entomology and Vector Control, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The brown-banded cockroach, Supella longipalpa (Blattaria: Blattellidae) (S. longipalpa), Received 16 Jun 2015 recently has infested the buildings and hospitals in wide areas of Iran, and this review was Received in revised form 3 Jul 2015, prepared to identify current knowledge and knowledge gaps about the brown-banded 2nd revised form 7 Jun, 3rd revised cockroach. Scientific reports and peer-reviewed papers concerning S. longipalpa and form 18 Jul 2016 relevant topics were collected and synthesized with the objective of learning more about Accepted 10 Aug 2016 health-related impacts and possible management of S. longipalpa in Iran. Like the Available online 15 Oct 2016 German cockroach, the brown-banded cockroach is a known vector for food-borne dis- eases and drug resistant bacteria, contaminated by infectious disease agents, involved in human intestinal parasites and is the intermediate host of Trichospirura leptostoma and Keywords: Moniliformis moniliformis. Because its habitat is widespread, distributed throughout Brown-banded cockroach different areas of homes and buildings, it is difficult to control. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Isolation

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Isolation, Determination of Absolute Stereochemistry, and Asymmetric Synthesis of Insect Methyl-Branched Hydrocarbons A Dissertation submitted in the partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chemistry by Jan Edgar Bello June 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jocelyn G. Millar, Chairperson Dr. Thomas H. Morton Dr. Catharine Larsen Copyright by Jan Edgar Bello 2014 The Dissertation of Jan Edgar Bello is approved: ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the guidance, assistance, and support from both my academic and biological families. I would first and foremost like to thank my advisor Professor Jocelyn G. Millar, who has guided me through this rigorous process and has helped me become the chemical ecologist I am today. I would also like to thank my research group Dr. Steve McElfresh, Dr. Yunfan Zou, Dr. Rebeccah Waterworth, R. Max Collignon, Joshua Rodstein, Jackie Serrano, and Brian Hanley for all the suggestions, insect collecting, synthetic discussions, and experimental advise that have allowed me to complete this dissertation. I would like to send a huge thank you to my family who have always believed in me. To my mom and dad, thank you for your encouragement, for loving me, and for your support (both financial and emotional). To my siblings, Jonathan, Michelle, and John-C thank you for your encouragement and for praying for me, especially during the beginning of my PhD studies when things were overwhelming. I would also like to thank my friends, Ryan Neff, Lauren George, Jenifer N. -

A New Insect Trackway from the Upper Jurassic—Lower Cretaceous Eolian Sandstones of São Paulo State, Brazil: Implications for Reconstructing Desert Paleoecology

A new insect trackway from the Upper Jurassic—Lower Cretaceous eolian sandstones of São Paulo State, Brazil: implications for reconstructing desert paleoecology Bernardo de C.P. e M. Peixoto1,2, M. Gabriela Mángano3, Nicholas J. Minter4, Luciana Bueno dos Reis Fernandes1 and Marcelo Adorna Fernandes1,2 1 Laboratório de Paleoicnologia e Paleoecologia, Departamento de Ecologia e Biologia Evolutiva, Universidade Federal de São Carlos (UFSCar), São Carlos, São Paulo, Brazil 2 Programa de Pós Graduacão¸ em Ecologia e Recursos Naturais, Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde, Universidade Federal de São Carlos (UFSCar), São Carlos, São Paulo, Brazil 3 Department of Geological Sciences, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada 4 School of the Environment, Geography, and Geosciences, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, Hampshire, United Kingdom ABSTRACT The new ichnospecies Paleohelcura araraquarensis isp. nov. is described from the Upper Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous Botucatu Formation of Brazil. This formation records a gigantic eolian sand sea (erg), formed under an arid climate in the south-central part of Gondwana. This trackway is composed of two track rows, whose internal width is less than one-quarter of the external width, with alternating to staggered series, consisting of three elliptical tracks that can vary from slightly elongated to tapered or circular. The trackways were found in yellowish/reddish sandstone in a quarry in the Araraquara municipality, São Paulo State. Comparisons with neoichnological studies and morphological inferences indicate that the producer of Paleohelcura araraquarensis isp. nov. was most likely a pterygote insect, and so could have fulfilled one of the Submitted 6 November 2019 ecological roles that different species of this group are capable of performing in dune Accepted 10 March 2020 deserts. -

Social Context Modulates Idiosyncrasy of Behaviour in the Gregarious Cockroach Blaberus Discoidalis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/028571; this version posted October 8, 2015. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Crall, Souffrant, Akandwanaho & Hescock, et al. 2015 – preprint version Social context modulates idiosyncrasy of behaviour in the gregarious cockroach Blaberus discoidalis James D. Crall1,2,*, André D. Souffrant1,*, Dominic Akandwanaho1,*, Sawyer D. Hescock1,*, Sarah E. Callan1,†, W. Melissa Coronado1,†, Maude W. Baldwin1, Benjamin L. de Bivort1,3,‡ 1 – Dept. of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA. 2 – Concord Field Station, Harvard University, Bedford, MA 01730, USA. 3 – Center for Brain Science, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA. * These authors contributed equally. † These authors contributed equally. ‡ Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Individuals are different, but they can work together to perform adaptive collective behaviours. Despite emerging evidence that individual variation strongly affects group performance, it is less clear to what extent individual variation is modulated by participation in collective behaviour. We examined light avoidance (negative phototaxis) in the gregarious cockroach Blaberus discoidalis, in both solitary and group contexts. Cockroaches in groups exhibit idiosyncratic light-avoidance performance that persists across days, with some individual cockroaches avoiding a light stimulus 75% of the time, and others avoiding the light just above chance (i.e. ~50% of the time). These individual differences are robust to group composition. Surprisingly, these differences do not persist when individuals are tested in isolation, but return when testing is once again done with groups. -

Assessing the Efficiency of Molecular Markers for the Species Identification of Gregarines Isolated from the Mealworm and Super Worm Midgut

Microorganisms 2018, 6, 119 1 of 20 Article Assessing the Efficiency of Molecular Markers for the Species Identification of Gregarines Isolated from the Mealworm and Super Worm Midgut Chiara Nocciolini 1, Claudio Cucini 2, Chiara Leo 2, Valeria Francardi 3, Elena Dreassi 4 and Antonio Carapelli 2,* 1 Polo d’Innovazione di Genomica Genetica e Biologia, 53100 Siena, Italy; [email protected] 2 Department of Life Sciences, University of Siena, 53100 Siena, Italy; [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (C.L.) 3 Consiglio per la ricerca in agricoltura e analisi dell’economia agraria – Centro di Difesa e Certificazione CREA-DC) Research Centre for Plant Protection and Certification, via di Lanciola 12/A, 50125 Firenze, Italy; [email protected] 4 Department of Biotechnology, Chemistry and Pharmacy, University of Siena, 53100 Siena, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-0577-234-410 Received: 28 September 2018; Accepted: 23 November 2018; Published: 27 November 2018 Abstract: Protozoa, of the taxon Gregarinasina, are a heterogeneous group of Apicomplexa that includes ~1600 species. They are parasites of a large variety of both marine and terrestrial invertebrates, mainly annelids, arthropods and mollusks. Unlike coccidians and heamosporidians, gregarines have not proven to have a negative effect on human welfare; thus, they have been poorly investigated. This study focuses on the molecular identification and phylogeny of the gregarine species found in the midgut of two insect species that are considered as an alternative source of animal proteins for the human diet: the mealworm Tenebrio molitor, and the super-worm Zophobas atratus (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). -

In the Cockroach, Blaberus Discoidalis

J Comp Physiol A (1998) 182: 23±33 Ó Springer-Verlag 1998 ORIGINAL PAPER J. T. Watson á R. E. Ritzmann Leg kinematics and muscle activity during treadmill running in the cockroach, Blaberus discoidalis : II. Fast running Accepted: 24 May 1997 Abstract We have combined kinematic and electromy- ogram (EMG) analysis of running Blaberus discoidalis to Introduction examine how middle and hind leg kinematics vary with Arthropod neuromuscular systems provide useful mod- running speed and how the fast depressor coxa (Df) and els in which to study problems involving control of lo- fast extensor tibia (FETi) motor neurons aect kine- comotion. The legs of various arthropods are matic parameters. In the range 2.5±10 Hz, B. discoidalis characterized by a pattern of few motor neurons sup- increases step frequency by altering the joint velocity plying each muscle, with each motor neuron having and by reducing the time required for the transition from markedly diverse properties. In all insects studied so far, ¯exion to extension. For both Df and FETi the timing of femoral depressor and tibial extensor muscles that are recruitment coincides with the maximal frequency seen used during stance are innervated by at most three axons for the respective slow motor neurons. Df is ®rst re- (Pearson and Iles 1971; Burrows and Hoyle 1972; Wil- cruited at the beginning of coxa-femur (CF) extension. son 1979). The triply innervated muscles receive a single FETi is recruited in the latter half of femur-tibia (FT) slow excitatory axon, a single fast excitatory axon, and a extension during stance. Single muscle potentials pro- common inhibitory axon shared with an undetermined duced by these fast motor neurons do not have pro- number of other muscles. -

Behavioral Ecology Symposium '94: Thomas 39 INVERTEBRATE PETS

Behavioral Ecology Symposium ’94: Thomas 39 INVERTEBRATE PETS AND THE FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE AND CONSUMER SERVICES MICHAEL C. THOMAS Division of Plant Industry, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services P.O. Box 147100, Gainesville, FL 32614-7100 ABSTRACT The Division of Plant Industry (DPI) of the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services now regulates importation into Florida of all arthropods except Crustacea, no longer just those of actual or potential agricultural importance. The op- erating law is Chapter 581.083 of the Florida Statutes, and the operating procedure is Title 5B-57.004 of the Florida Administrative Code. The current law was proposed because of importation by the pet trade of species that did not already occur in Florida and were potentially harmful to the environment. The Division requires specimens (for confirmation of identification) to accompany applications for permits. Key Words: Exotic species, introduction, Florida, permits, insects RESUMEN La División de la Industria de los Vegetales (DPI) del Departamento de Agricul- tura y Servicios al Consumidor de la Florida, ahora regula la importación a la Florida de todos los artrópodos (excepto crustáceos) y no únicamente de aquellos con impor- tancia real o potencial para la agricultura. La ley es el Capítulo 581.083 de los Esta- tutos de la Florida, y el procedimiento operativo es el Título 5B-57.004 del Código Administrativo de la Florida. La ley actual fué propuesta debido a la importación por los comerciantes de mascotas de especies que no existen naturalmente en Florida y que potentialmente pueden ser dañinas al medioambiente. La División requiere que las solicitudes de permisos sean acompañnadas por especímenes (para confirmar la identificación). -

False Death's Head Cockroaches Latin Name:Blaberus Discoidalis

Husbandry Data Sheet Common Name: False Death's Head Cockroaches Latin Name:Blaberus discoidalis Family:Blaberidae Order:Dictyoptera Class:Insecta Phylum:Arthropoda Natural History:The False Death's Head Cockroach (Blaberus discoidalis) is found throughout the northern part of South America. In the wild this species can be found in caves, holes in trees and under bark. During mating behaviour the males ‘pump’ their wings, raising them up and down to attract the attention of the female. This cockroach, like many others, produces a distinctive smell when attacked. Permits Required:Yes Life Stage:All Ease of Care:Easy Housing: Temp:75-85 degrees F Humidity:60%-80% Substrate:50:50 mixture of sand and compost. # of Animals per Exhibit:200 Choose One:Colony Compatible Species:N/A Enclosure Description: 10 gallon aquarium. Lighting/Photoperiod: Flourescent lighting on a 12 hour period. Furniture/Props:4" plastic coated hardware cloth climbing structure and plastic tubes. Escape Concerns:Although this species is not noted as being a climber, a screen cover is securely fastened to the tank. Other Concerns/Precautions: Husbandry Diet/Frequency of Feeding:Mixed vegetables and Mazuri primate biscuits Water Source/FrequencyMoisture from food as well as a 4" petri dish with rocks. Care: Daily Enrichment:Cork bark to hide under and wire tubes for climbing structres. Medical/Health Concerns:If the soil becomes too moist mites can become a challenge. Treatment:Substrate change or drying out the sunstrate help keep the mites under control. Keeper Safety: N/A Other Concerns/Precautions:All old food and substrate is placed in a freezer for one week prior to being discarded to destroy any nymphs missed in cleaning. -

Mechanosensation and Adaptive Motor Control in Insects

Current Biology Review Mechanosensation and Adaptive Motor Control in Insects John C. Tuthill1 and Rachel I. Wilson2 1Department of Physiology and Biophysics, University of Washington, 1705 NE Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA 2Department of Neurobiology, Harvard Medical School, 220 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA Correspondence: [email protected] (J.C.T.), [email protected] (R.I.W.) http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2016.06.070 The ability of animals to flexibly navigate through complex environments depends on the integration of sen- sory information with motor commands. The sensory modality most tightly linked to motor control is mecha- nosensation. Adaptive motor control depends critically on an animal’s ability to respond to mechanical forces generated both within and outside the body. The compact neural circuits of insects provide appealing sys- tems to investigate how mechanical cues guide locomotion in rugged environments. Here, we review our cur- rent understanding of mechanosensation in insects and its role in adaptive motor control. We first examine the detection and encoding of mechanical forces by primary mechanoreceptor neurons. We then discuss how central circuits integrate and transform mechanosensory information to guide locomotion. Because most studies in this field have been performed in locusts, cockroaches, crickets, and stick insects, the exam- ples we cite here are drawn mainly from these ‘big insects’. However, we also pay particular attention to the tiny fruit fly, Drosophila, where new tools are creating new opportunities, particularly for understanding cen- tral circuits. Our aim is to show how studies of big insects have yielded fundamental insights relevant to mechanosensation in all animals, and also to point out how the Drosophila toolkit can contribute to future progress in understanding mechanosensory processing. -

Characterization of Obstacle Negotiation Behaviors in the Cockroach, Blaberus Discoidalis

1463 The Journal of Experimental Biology 212, 1463-1476 Published by The Company of Biologists 2009 doi:10.1242/jeb.028381 Characterization of obstacle negotiation behaviors in the cockroach, Blaberus discoidalis C. M. Harley*, B. A. English and R. E. Ritzmann Department of Biology, Case Western Reserve University, 10900 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 4 March 2009 SUMMARY Within natural environments, animals must be able to respond to a wide range of obstacles in their path. Such responses require sensory information to facilitate appropriate and effective motor behaviors. The objective of this study was to characterize sensors involved in the complex control of obstacle negotiation behaviors in the cockroach Blaberus discoidalis. Previous studies suggest that antennae are involved in obstacle detection and negotiation behaviors. During climbing attempts, cockroaches swing their front leg that then either successfully reaches the top of the block or misses. The success of these climbing attempts was dependent on their distance from the obstacle. Cockroaches with shortened antennae were closer to the obstacle prior to climbing than controls, suggesting that distance was related to antennal length. Removing the antennal flagellum resulted in delays in obstacle detection and changes in climbing strategy from targeted limb movements to less directed attempts. A more complex scenario – a shelf that the cockroach could either climb over or tunnel under – allowed us to further examine the role of sensory involvement in path selection. Ultimately, antennae contacting the top of the shelf led to climbing whereas contact on the underside led to tunneling However, in the light, cockroaches were biased toward tunnelling; a bias which was absent in the dark. -

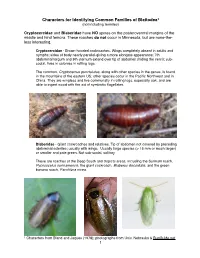

Characters for Identifying Common Families of Blattodea1 (Not Including Termites)

Characters for Identifying Common Families of Blattodea1 (not including termites) Cryptocercidae and Blaberidae have NO spines on the posteroventral margins of the middle and hind femora. These roaches do not occur in Minnesota, but are none-the- less interesting. Cryptocercidae - Brown-hooded cockroaches. Wings completely absent in adults and nymphs; sides of body nearly parallel-giving a more elongate appearance; 7th abdominal tergum and 6th sternum extend over tip of abdomen (hiding the cerci); sub- social, lives in colonies in rotting logs. The common, Cryptocercus punctulatus, along with other species in the genus, is found in the mountains of the eastern US; other species occur in the Pacific Northwest and in China. They are wingless and live communally in rotting logs, especially oak, and are able to ingest wood with the aid of symbiotic flagellates. Blaberidae - Giant cockroaches and relatives. Tip of abdomen not covered by preceding abdominal sclerites; usually with wings. Usually large species (> 15 mm or much larger) or smaller and pale green. Not sub-social, solitary These are roaches of the Deep South and tropical areas, including the Surinam roach, Pycnoscelus surinamensis, the giant cockroach, Blaberus discoidalis, and the green banana roach, Panchlora nivea. 1 Characters from Bland and Jaques (1978); photographs from Univ. Nebraska & BugGuide.net !1 Ectobiidae (=Blattellidae)2 and Blattidae have numerous spines on the posteroventral margins of the middle and hind femora. These roaches do occur in Minnesota. Ectobiidae (=Blattellidae) (in part) - Parcoblatta. Front femur with row of stout spines on posteroventral margin and with shorter and more slender spines basally (in other words, the spines are in 2 distinct size groups). -

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 122, NUMBER 12 THE REPRODUCTION OF COCKROACHES (With 12 Plates) BY LOUIS M. ROTH AND EDWIN R. WILLIS Pioneering Research Laboratories U. S. Army Quartermaster Corps Philadelphia, Pa. (Publication 4148) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION JUNE 9, 1954 SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 122, NUMBER 12 THE REPRODUCTION OF COCKROACHES (With 12 Plates) BY LOUIS M. ROTH AND EDWIN R. WILLIS Pioneering Research Laboratories U. S. Army Quartermaster Corps Philadelphia, Pa. (Publication 4148) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION JUNE 9, 1954 BALTIMORE, MD., U. 0. A. THE REPRODUCTION OF COCKROACHES 1 By LOUIS M. ROTH and EDWIN R. WILLIS Pioneering Research Laboratories U. S. Army Quartermaster Corps Philadelphia, Pa. (With 12 Plates) INTRODUCTION Cockroaches are important for several reasons. As pests, many are omnivorous, feeding on and defiling our foodstuffs, books, and other possessions. What is perhaps less well known is their relation to the spreading of disease. Several species of cockroaches closely associated with man have been shown to be capable of carrying and transmitting various microorganisms (Cao, 1898; Morrell, 191 1 ; Herms and Nel- a resurgence of inter- son, 191 3 ; and others). Recently there has been est in this subject, and some workers have definitely implicated cock- roaches in outbreaks of gastroenteritis. Antonelli (1930) recovered typhoid bacilli from the feet and bodies of Blatta orientalis Linnaeus which he found in open latrines during two small outbreaks of typhoid fever. Mackerras and Mackerras (1948), studying gastroenteritis in children in a Brisbane hospital, isolated two strains of Salmonella from Periplaneta americana (Lin- naeus) and Nauphoeta cinerea (Olivier) that were caught in the hos- pital wards.