Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Aspects About Supella Longipalpa (Blattaria: Blattellidae)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2016; 6(12): 1065–1075 1065 HOSTED BY Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/apjtb Review article http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apjtb.2016.08.017 New aspects about Supella longipalpa (Blattaria: Blattellidae) Hassan Nasirian* Department of Medical Entomology and Vector Control, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The brown-banded cockroach, Supella longipalpa (Blattaria: Blattellidae) (S. longipalpa), Received 16 Jun 2015 recently has infested the buildings and hospitals in wide areas of Iran, and this review was Received in revised form 3 Jul 2015, prepared to identify current knowledge and knowledge gaps about the brown-banded 2nd revised form 7 Jun, 3rd revised cockroach. Scientific reports and peer-reviewed papers concerning S. longipalpa and form 18 Jul 2016 relevant topics were collected and synthesized with the objective of learning more about Accepted 10 Aug 2016 health-related impacts and possible management of S. longipalpa in Iran. Like the Available online 15 Oct 2016 German cockroach, the brown-banded cockroach is a known vector for food-borne dis- eases and drug resistant bacteria, contaminated by infectious disease agents, involved in human intestinal parasites and is the intermediate host of Trichospirura leptostoma and Keywords: Moniliformis moniliformis. Because its habitat is widespread, distributed throughout Brown-banded cockroach different areas of homes and buildings, it is difficult to control. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Isolation

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Isolation, Determination of Absolute Stereochemistry, and Asymmetric Synthesis of Insect Methyl-Branched Hydrocarbons A Dissertation submitted in the partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chemistry by Jan Edgar Bello June 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Jocelyn G. Millar, Chairperson Dr. Thomas H. Morton Dr. Catharine Larsen Copyright by Jan Edgar Bello 2014 The Dissertation of Jan Edgar Bello is approved: ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the guidance, assistance, and support from both my academic and biological families. I would first and foremost like to thank my advisor Professor Jocelyn G. Millar, who has guided me through this rigorous process and has helped me become the chemical ecologist I am today. I would also like to thank my research group Dr. Steve McElfresh, Dr. Yunfan Zou, Dr. Rebeccah Waterworth, R. Max Collignon, Joshua Rodstein, Jackie Serrano, and Brian Hanley for all the suggestions, insect collecting, synthetic discussions, and experimental advise that have allowed me to complete this dissertation. I would like to send a huge thank you to my family who have always believed in me. To my mom and dad, thank you for your encouragement, for loving me, and for your support (both financial and emotional). To my siblings, Jonathan, Michelle, and John-C thank you for your encouragement and for praying for me, especially during the beginning of my PhD studies when things were overwhelming. I would also like to thank my friends, Ryan Neff, Lauren George, Jenifer N. -

A New Insect Trackway from the Upper Jurassic—Lower Cretaceous Eolian Sandstones of São Paulo State, Brazil: Implications for Reconstructing Desert Paleoecology

A new insect trackway from the Upper Jurassic—Lower Cretaceous eolian sandstones of São Paulo State, Brazil: implications for reconstructing desert paleoecology Bernardo de C.P. e M. Peixoto1,2, M. Gabriela Mángano3, Nicholas J. Minter4, Luciana Bueno dos Reis Fernandes1 and Marcelo Adorna Fernandes1,2 1 Laboratório de Paleoicnologia e Paleoecologia, Departamento de Ecologia e Biologia Evolutiva, Universidade Federal de São Carlos (UFSCar), São Carlos, São Paulo, Brazil 2 Programa de Pós Graduacão¸ em Ecologia e Recursos Naturais, Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde, Universidade Federal de São Carlos (UFSCar), São Carlos, São Paulo, Brazil 3 Department of Geological Sciences, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada 4 School of the Environment, Geography, and Geosciences, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, Hampshire, United Kingdom ABSTRACT The new ichnospecies Paleohelcura araraquarensis isp. nov. is described from the Upper Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous Botucatu Formation of Brazil. This formation records a gigantic eolian sand sea (erg), formed under an arid climate in the south-central part of Gondwana. This trackway is composed of two track rows, whose internal width is less than one-quarter of the external width, with alternating to staggered series, consisting of three elliptical tracks that can vary from slightly elongated to tapered or circular. The trackways were found in yellowish/reddish sandstone in a quarry in the Araraquara municipality, São Paulo State. Comparisons with neoichnological studies and morphological inferences indicate that the producer of Paleohelcura araraquarensis isp. nov. was most likely a pterygote insect, and so could have fulfilled one of the Submitted 6 November 2019 ecological roles that different species of this group are capable of performing in dune Accepted 10 March 2020 deserts. -

Pdf 696.18 K

Egypt. Acad. J. Biolog. Sci., 13(3):1-13 (2020) Egyptian Academic Journal of Biological Sciences A. Entomology ISSN 1687- 8809 http://eajbsa.journals.ekb.eg/ The Mymaridae of Egypt (Chalcidoidea: Hymenoptera) Al-Azab, S. A. Plant Protection Research Institute, ARC, Egypt. Email: [email protected] ______________________________________________________________ ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History Diagnostic characters of the family Mymaridae, together with diagnosis Received:15/5/2020 and keys to the Egyptian genera of the family-based upon the external Accepted:2/7/2020 morphological characters of the adult female and male are presented with ---------------------- illustrations to facilitate their recognition. Synonyms, taxonomic notes, hosts, Keywords: and habitat of the genera together with their representative species in Egypt Hymenoptera, are also provided to give general picture and high light on the occurrence, Chalcidoidea, diversity, and distribution of the mymarids in Egypt. The study based on the Mymaridae, materials kept in the main reference insect collections in Egypt, and the Taxonomy, available literature. Egypt. INTRODUCTION The Mymaridae (fairy wasps) are a family of chalcid wasps found in temperate and tropical regions throughout the world. It includes the most primitive members of the chalcid wasp and contains around 100 genera with about 1400 species (Noyes, 2005). Fairyflies are very tiny insects and include the world's smallest known insects. They generally range from 0.5 to 1.0 mm long. Adult mymarids are rather fragile, the body generally being slender and the wings narrow with an elongate marginal fringe. Their delicate bodies and their hair-fringed wings have earned them their common name. Very little is known of the life histories of fairyflies, as only a few species have been observed extensively. -

Effects of House and Landscape Characteristics on the Abundance and Diversity of Perimeter Pests Principal Investigators: Arthur G

Project Final Report presented to: The Pest Management Foundation Board of Trustees Project Title: Effects of house and landscape characteristics on the abundance and diversity of perimeter pests Principal Investigators: Arthur G. Appel and Xing Ping Hu, Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, Auburn University Date: June 17, 2019 Executive Summary: The overall goal of this project was to expand and refine our statistical model that estimates Smokybrown cockroach abundance from house and landscape characteristics to include additional species of cockroaches, several species of ants as well as subterranean termites. The model will correlate pest abundance and diversity with house and landscape characteristics. These results could ultimately be used to better treat and prevent perimeter pest infestations. Since the beginning of the period of performance (August 1, 2017), we have hired two new Master’s students, Patrick Thompson and Gökhan Benk, to assist with the project. Both students will obtain degrees in entomology with a specialization in urban entomology with anticipated graduation dates of summer-fall 2019. We have developed and tested several traps designs for rapidly collecting sweet and protein feeding ants, purchased and modified traps for use during a year of trapping, and have identified species of ants, cockroaches, and termites found around homes in Auburn Alabama. House and landscape characteristics have been measured at 62 single-family homes or independent duplexes. These homes range in age from 7 to 61 years and include the most common different types of siding (brick, metal, stone, vinyl, wood), different numbers/types of yard objects (none to >15, including outbuildings, retaining walls, large ornamental rocks, old trees, compost piles, etc.), and different colors. -

Harmful Non-Indigenous Species in the United States

Harmful Non-Indigenous Species in the United States September 1993 OTA-F-565 NTIS order #PB94-107679 GPO stock #052-003-01347-9 Recommended Citation: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, Harmful Non-Indigenous Species in the United States, OTA-F-565 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, September 1993). For Sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office ii Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop, SSOP. Washington, DC 20402-9328 ISBN O-1 6-042075-X Foreword on-indigenous species (NIS)-----those species found beyond their natural ranges—are part and parcel of the U.S. landscape. Many are highly beneficial. Almost all U.S. crops and domesticated animals, many sport fish and aquiculture species, numerous horticultural plants, and most biologicalN control organisms have origins outside the country. A large number of NIS, however, cause significant economic, environmental, and health damage. These harmful species are the focus of this study. The total number of harmful NIS and their cumulative impacts are creating a growing burden for the country. We cannot completely stop the tide of new harmful introductions. Perfect screening, detection, and control are technically impossible and will remain so for the foreseeable future. Nevertheless, the Federal and State policies designed to protect us from the worst species are not safeguarding our national interests in important areas. These conclusions have a number of policy implications. First, the Nation has no real national policy on harmful introductions; the current system is piecemeal, lacking adequate rigor and comprehensiveness. Second, many Federal and State statutes, regulations, and programs are not keeping pace with new and spreading non-indigenous pests. -

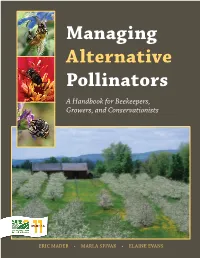

Managing Alternative Pollinators a Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists

Managing Alternative Pollinators A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists ERIC MADER • MARLA SPIVAK • ELAINE EVANS Fair Use of this PDF file of Managing Alternative Pollinators: A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists, SARE Handbook 11, NRAES-186 By Eric Mader, Marla Spivak, and Elaine Evans Co-published by SARE and NRAES, February 2010 You can print copies of the PDF pages for personal use. If a complete copy is needed, we encourage you to purchase a copy as described below. Pages can be printed and copied for educational use. The book, authors, SARE, and NRAES should be acknowledged. Here is a sample acknowledgement: ----From Managing Alternative Pollinators: A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists, SARE Handbook 11, by Eric Mader, Marla Spivak, and Elaine Evans, and co- published by SARE and NRAES.---- No use of the PDF should diminish the marketability of the printed version. If you have questions about fair use of this PDF, contact NRAES. Purchasing the Book You can purchase printed copies on NRAES secure web site, www.nraes.org, or by calling (607) 255-7654. The book can also be purchased from SARE, visit www.sare.org. The list price is $23.50 plus shipping and handling. Quantity discounts are available. SARE and NRAES discount schedules differ. NRAES PO Box 4557 Ithaca, NY 14852-4557 Phone: (607) 255-7654 Fax: (607) 254-8770 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nraes.org SARE 1122 Patapsco Building University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742-6715 (301) 405-8020 (301) 405-7711 – Fax www.sare.org More information on SARE and NRAES is included at the end of this PDF. -

Cockroach Marion Copeland

Cockroach Marion Copeland Animal series Cockroach Animal Series editor: Jonathan Burt Already published Crow Boria Sax Tortoise Peter Young Ant Charlotte Sleigh Forthcoming Wolf Falcon Garry Marvin Helen Macdonald Bear Parrot Robert E. Bieder Paul Carter Horse Whale Sarah Wintle Joseph Roman Spider Rat Leslie Dick Jonathan Burt Dog Hare Susan McHugh Simon Carnell Snake Bee Drake Stutesman Claire Preston Oyster Rebecca Stott Cockroach Marion Copeland reaktion books Published by reaktion books ltd 79 Farringdon Road London ec1m 3ju, uk www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2003 Copyright © Marion Copeland All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Printed and bound in Hong Kong British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Copeland, Marion Cockroach. – (Animal) 1. Cockroaches 2. Animals and civilization I. Title 595.7’28 isbn 1 86189 192 x Contents Introduction 7 1 A Living Fossil 15 2 What’s in a Name? 44 3 Fellow Traveller 60 4 In the Mind of Man: Myth, Folklore and the Arts 79 5 Tales from the Underside 107 6 Robo-roach 130 7 The Golden Cockroach 148 Timeline 170 Appendix: ‘La Cucaracha’ 172 References 174 Bibliography 186 Associations 189 Websites 190 Acknowledgements 191 Photo Acknowledgements 193 Index 196 Two types of cockroach, from the first major work of American natural history, published in 1747. Introduction The cockroach could not have scuttled along, almost unchanged, for over three hundred million years – some two hundred and ninety-nine million before man evolved – unless it was doing something right. -

Download 1 File

PROC. ENTOMOL. SOC. WASH. 83(4). 1981. pp. 592-595 THE FOREST COCKROACH, ECTOBIUS SYLVESTRIS (PODA), A EUROPEAN SPECIES NEWLY DISCOVERED IN NORTH AMERICA (DICTYOPTERA: BLATTODEA: ECTOBIIDAE) E. Richard Hoebeke and David A. Nickle (ERH) Department of Entomology, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853; (DAN) Systematic Entomology Laboratory, IIBIII, Agric. Res., Sci. and Educ. Admin., USDA, Vc National Museum of Natural History, Wash- ington, D.C. 20560. Abstract. —Ectohius sylvestris (Poda) was collected in 1980 in New York State, the first record of this European species for North America. This is the second European member of the genus Ectohius potentially to become established in North America. Ectohius syh'estris is described briefly, and its dorsal habitus and external male characters are illustrated. Heifer's key to the cockroach species occurring in North America is modified to include E. sylvestris. A European cockroach, Ectohius sylvestris (Poda), was detected in North America in June 1980 with the collection of a single male specimen in a home at Geneva, New York'. One of us (ERH) received this specimen for identification: it did not agree with any of the native North American species, but it did key readily to E. sylvestris in the European literature (Chopard, 1951; Princis, 1965; Harz and Kaltenbach, 1976). This specimen was sent to DAN for confirmation. In this paper, we discuss recognition features, known distribution, biol- ogy, and habits of E. sylvestris. Only one other species of the genus Ec- tohius, E. pallidus (Olivier), has been reported in the United States (Flint, 1951; cited as lividus (Fabricius)). Distinctive characters of E. -

Comparative Reproductive Biology of Two Florida Pawpaws Asimina Reticulata Chapman and Asimina Tetramera Small Anne Cheney Cox Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-5-1998 Comparative reproductive biology of two Florida pawpaws asimina reticulata chapman and asimina tetramera small Anne Cheney Cox Florida International University DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14061532 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Cox, Anne Cheney, "Comparative reproductive biology of two Florida pawpaws asimina reticulata chapman and asimina tetramera small" (1998). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2656. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/2656 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida COMPARATIVE REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY OF TWO FLORIDA PAWPAWS ASIMINA RETICULATA CHAPMAN AND ASIMINA TETRAMERA SMALL A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in BIOLOGY by Anne Cheney Cox To: A rthur W. H arriott College of Arts and Sciences This dissertation, written by Anne Cheney Cox, and entitled Comparative Reproductive Biology of Two Florida Pawpaws, Asimina reticulata Chapman and Asimina tetramera Small, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgement. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. Jorsre E. Pena Steven F. Oberbauer Bradley C. Bennett Daniel F. Austin Suzanne Koptur, Major Professor Date of Defense: November 5, 1998 The dissertation of Anne Cheney Cox is approved. -

Scrub Oak Preserve Animal Checklist Volusia County, Florida

Scrub Oak Preserve Animal Checklist Volusia County, Florida Accipitridae Cervidae Cooper's Hawk Accipiter cooperii White-tailed Deer Odocoileus virginianus Red-tailed Hawk Buteo jamaicensis Red-shouldered Hawk Buteo lineatus Charadriidae Bald Eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Acrididae Corvidae American Bird Grasshopper Schistocerca americana Scrub Jay Aphelocoma coerulescens American Crow Corvus brachyrhynchos Agelenidae Fish Crow Corvus ossifragus Grass Spider Agelenopsis sp. Blue Jay Cyanocitta cristata Anatidae Dactyloidae Wood Duck Aix sponsa Cuban Brown Anole Anolis sagrei Blattidae Elateridae Florida woods cockroach Eurycotis floridana Eyed Click Beetle Alaus oculatus Bombycillidae Emberizidae Cedar Waxwing Bombycilla cedrorum Eastern Towhee Pipilo erythrophthalmus Cardinalidae Eumenidae Northern Cardinal Cardinalis cardinalis Paper wasp Polistes sp. Cathartidae Formicidae Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura Carpenter ants Camponotus sp. Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Fire Ant Solenopsis invicta Certhiidae Fringillidae Blue-gray Gnatcatcher Polioptila caerulea American Goldfinch Carduelis tristis Geomyidae Phalacrocoracidae Southeastern Pocket Gopher Geomys pinetis Double-crested Cormorant Phalacrocorax auritus Gruidae Picidae Sandhill Crane Grus canadensis Northern Flicker Colaptes auratus Pileated Woodpecker Dryocopus pileatus Hesperiidae Red-bellied Woodpecker Melanerpes carolinus Duskywing Erynnis sp. Downy Woodpecker Picoides pubescens Hirundinidae Polychrotidae Tree Swallow Tachycineta bicolor Green Anole -

The American Cockroach, Periplaneta Americana Linnaeus, As a Disseminator of Some Salmonella Bacteria

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1943 The American cockroach, Periplaneta americana Linnaeus, as a disseminator of some Salmonella bacteria. Arnold Erwin Fischman University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Fischman, Arnold Erwin, "The American cockroach, Periplaneta americana Linnaeus, as a disseminator of some Salmonella bacteria." (1943). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 5573. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/5573 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 3120bfc. 0230 2b3D b '! HE AMERICAN COCKROACH, ITiRIPEANETA AMERICANA LINNAEUS AS A DISSEMINATOR OF SOME SAl_.MONEL.LA BACTERIA — 111 F1SCHMAN - 1843 MORR LD 3234 ! M267 11943 F529 THK A&SBiCAjf cockroach, mSSSABk NKEJBUk ummxjs AS A PISSE’CHATOR CHP SO* RkUKMSUL BACTERIA Arnold Erwin Plachaan Thesis subaittetf in partial fulfill wont of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Riiloeophy Shseaohuaetta State College May, 1943 TABLE OP COSmtrs Jhge X. INTKGfUCTIGN .... 1 1. Origin, I-iatribution and Abundance of the Cockroach 1 2. Importance of the Cockroach •••••••••••••• 2 II. RETIES OP LITERATURE .. 6 1. Morphology of the Cockroach •••••••••••••• 7 2. Pevelopment of the Cockroach •••••••••••.. 7 3* Biology of the American Cockroach, Perl- nlcrmt* aaarloana Linnaeus •••••••••••• 8 4* Control .. 10 5. Bacteria and the Cockroach .. 12 6. Virus and the Cockroach 25 7. FUngi and the Cockroach ••»•••••••••••.••• 25 8.