Clinical Implications of Next-Generation Sequencing for Cancer Medicine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

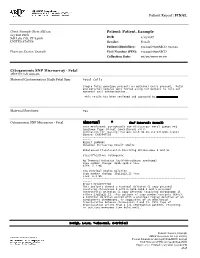

Cytogenomic SNP Microarray - Fetal ARUP Test Code 2002366 Maternal Contamination Study Fetal Spec Fetal Cells

Patient Report |FINAL Client: Example Client ABC123 Patient: Patient, Example 123 Test Drive Salt Lake City, UT 84108 DOB 2/13/1987 UNITED STATES Gender: Female Patient Identifiers: 01234567890ABCD, 012345 Physician: Doctor, Example Visit Number (FIN): 01234567890ABCD Collection Date: 00/00/0000 00:00 Cytogenomic SNP Microarray - Fetal ARUP test code 2002366 Maternal Contamination Study Fetal Spec Fetal Cells Single fetal genotype present; no maternal cells present. Fetal and maternal samples were tested using STR markers to rule out maternal cell contamination. This result has been reviewed and approved by Maternal Specimen Yes Cytogenomic SNP Microarray - Fetal Abnormal * (Ref Interval: Normal) Test Performed: Cytogenomic SNP Microarray- Fetal (ARRAY FE) Specimen Type: Direct (uncultured) villi Indication for Testing: Patient with 46,XX,t(4;13)(p16.3;q12) (Quest: EN935475D) ----------------------------------------------------------------- ----- RESULT SUMMARY Abnormal Microarray Result (Male) Unbalanced Translocation Involving Chromosomes 4 and 13 Classification: Pathogenic 4p Terminal Deletion (Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome) Copy number change: 4p16.3p16.2 loss Size: 5.1 Mb 13q Proximal Region Deletion Copy number change: 13q11q12.12 loss Size: 6.1 Mb ----------------------------------------------------------------- ----- RESULT DESCRIPTION This analysis showed a terminal deletion (1 copy present) involving chromosome 4 within 4p16.3p16.2 and a proximal interstitial deletion (1 copy present) involving chromosome 13 within 13q11q12.12. This -

Differential Gene Expression in the Skin of Xiphophorus

DIFFERENTIAL GENE EXPRESSION IN THE SKIN OF XIPHOPHORUS MACULATUS JP 163 B IN RESPONSE TO FULL SPECTRUM (10,000 K) FLUORESCENT LIGHT by Kaela Caballero, B.S. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science with a Major in Biochemistry August 2015 Committee Members: Ronald Walter, Chair Rachell Booth Steven Whitten COPYRIGHT by Kaela L. Caballero 2015 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgment. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Kaela L. Caballero, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. DEDICATION To my parents and family, who have always supported and encouraged me, my education and my coffee addiction. And to Max, my study buddy; where you have gone, there is no need for coffee fueled late nights. Rest in peace. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work could not have been accomplished without the support and mentorship that I have received throughout my life from family, teachers, mentors and friends. It is impossible to name everyone here, but I would like to use a few lines to thank those that have helped me achieve my goals. Thank you to Dr. -

Nº Ref Uniprot Proteína Péptidos Identificados Por MS/MS 1 P01024

Document downloaded from http://www.elsevier.es, day 26/09/2021. This copy is for personal use. Any transmission of this document by any media or format is strictly prohibited. Nº Ref Uniprot Proteína Péptidos identificados 1 P01024 CO3_HUMAN Complement C3 OS=Homo sapiens GN=C3 PE=1 SV=2 por 162MS/MS 2 P02751 FINC_HUMAN Fibronectin OS=Homo sapiens GN=FN1 PE=1 SV=4 131 3 P01023 A2MG_HUMAN Alpha-2-macroglobulin OS=Homo sapiens GN=A2M PE=1 SV=3 128 4 P0C0L4 CO4A_HUMAN Complement C4-A OS=Homo sapiens GN=C4A PE=1 SV=1 95 5 P04275 VWF_HUMAN von Willebrand factor OS=Homo sapiens GN=VWF PE=1 SV=4 81 6 P02675 FIBB_HUMAN Fibrinogen beta chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=FGB PE=1 SV=2 78 7 P01031 CO5_HUMAN Complement C5 OS=Homo sapiens GN=C5 PE=1 SV=4 66 8 P02768 ALBU_HUMAN Serum albumin OS=Homo sapiens GN=ALB PE=1 SV=2 66 9 P00450 CERU_HUMAN Ceruloplasmin OS=Homo sapiens GN=CP PE=1 SV=1 64 10 P02671 FIBA_HUMAN Fibrinogen alpha chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=FGA PE=1 SV=2 58 11 P08603 CFAH_HUMAN Complement factor H OS=Homo sapiens GN=CFH PE=1 SV=4 56 12 P02787 TRFE_HUMAN Serotransferrin OS=Homo sapiens GN=TF PE=1 SV=3 54 13 P00747 PLMN_HUMAN Plasminogen OS=Homo sapiens GN=PLG PE=1 SV=2 48 14 P02679 FIBG_HUMAN Fibrinogen gamma chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=FGG PE=1 SV=3 47 15 P01871 IGHM_HUMAN Ig mu chain C region OS=Homo sapiens GN=IGHM PE=1 SV=3 41 16 P04003 C4BPA_HUMAN C4b-binding protein alpha chain OS=Homo sapiens GN=C4BPA PE=1 SV=2 37 17 Q9Y6R7 FCGBP_HUMAN IgGFc-binding protein OS=Homo sapiens GN=FCGBP PE=1 SV=3 30 18 O43866 CD5L_HUMAN CD5 antigen-like OS=Homo -

Sequencing Technology and Applica�Ons

Next Genera�on Sequencing technology and applica�ons Leonardo A. Meza-‐Zepeda, Ph.D. Genomics Core Facility Helse Sør-‐Øst/University of Oslo oslo.genomics.no Topics 7 Introduc�on 7 Technologies 7 Applica�ons oslo.genomics.no 1 Human Genome Project 3 billion bases Cost approx. 3 Billion Dollars Public HGP Celera Genomics 1990-‐2003 oslo.genomics.no Development of Sequencing Technologies Massively parallel sequencing Human Genome Project Stra�on MR et al, Nature 2009 oslo.genomics.no 2 Development of Sequencing Technologies last 10 years ER Mardis. Nature 470, 198-203 (2011) oslo.genomics.no Cost per Megabase oslo.genomics.no 3 Costs for a Human Genome Capillary Sequencing Next Genera�on Sequencing Applied Biosytems 3730xl HiSeq 2500 (2004) (Today) U$ 15,000,000 U$ 6,000 The Norwegian oslo.genomics.no Radium Hospital Sequencing Costs per Genome Costs Genomes $100M Venter 1M $10M 100k Watson $1M 10k African, Asian, Cancer pair $100k 169 in Genbank 1,000 Individual Genome Cost per Human Genome Human per Cost $10k Sequencing 100 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 Time oslo.genomics.no 4 Sequencing Technologies 7 Solexa (Illumina) 7 Sequencing by synthesis 7 454 (Roche) 7 Pyrosequencing 7 SOLiD (Life Technologies) 7 Sequencing by liga�on 7 Non op�cal 7 Ion Torrent/ Ion Proton 7 Single molecule sequencing 7 Helicos, Pacific Biosciences, Nanopores Oxford oslo.genomics.no Common a�ributes of commercial sequencers 7 Random fragmenta�on of DNA 7 Liga�on of adapter, crea�on of a library (genome/transcriptome) 7 Library amplifica�on on a solid surface 7 Direct sequencing for single molecule pla�orms 7 Direct step by step detec�on of nucleo�de incorpora�on 7 Shorter read length thank tradi�onal sequencers 7 Digital read type, enables direct quan�ta�ve comparisons 7 Possible to read both ends of a DNA fragment 7 Single read or Paired-‐end reads oslo.genomics.no 5 Single and Paired Ends Libraries Single Read Single Read Library (Up to 100bp) i.e. -

The Genetic Program of Pancreatic Beta-Cell Replication in Vivo

Page 1 of 65 Diabetes The genetic program of pancreatic beta-cell replication in vivo Agnes Klochendler1, Inbal Caspi2, Noa Corem1, Maya Moran3, Oriel Friedlich1, Sharona Elgavish4, Yuval Nevo4, Aharon Helman1, Benjamin Glaser5, Amir Eden3, Shalev Itzkovitz2, Yuval Dor1,* 1Department of Developmental Biology and Cancer Research, The Institute for Medical Research Israel-Canada, The Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School, Jerusalem 91120, Israel 2Department of Molecular Cell Biology, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel. 3Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, The Silberman Institute of Life Sciences, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem 91904, Israel 4Info-CORE, Bioinformatics Unit of the I-CORE Computation Center, The Hebrew University and Hadassah, The Institute for Medical Research Israel- Canada, The Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School, Jerusalem 91120, Israel 5Endocrinology and Metabolism Service, Department of Internal Medicine, Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center, Jerusalem 91120, Israel *Correspondence: [email protected] Running title: The genetic program of pancreatic β-cell replication 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online March 18, 2016 Diabetes Page 2 of 65 Abstract The molecular program underlying infrequent replication of pancreatic beta- cells remains largely inaccessible. Using transgenic mice expressing GFP in cycling cells we sorted live, replicating beta-cells and determined their transcriptome. Replicating beta-cells upregulate hundreds of proliferation- related genes, along with many novel putative cell cycle components. Strikingly, genes involved in beta-cell functions, namely glucose sensing and insulin secretion were repressed. Further studies using single molecule RNA in situ hybridization revealed that in fact, replicating beta-cells double the amount of RNA for most genes, but this upregulation excludes genes involved in beta-cell function. -

Supplementary Table S1. List of Differentially Expressed

Supplementary table S1. List of differentially expressed transcripts (FDR adjusted p‐value < 0.05 and −1.4 ≤ FC ≥1.4). 1 ID Symbol Entrez Gene Name Adj. p‐Value Log2 FC 214895_s_at ADAM10 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 3,11E‐05 −1,400 205997_at ADAM28 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 6,57E‐05 −1,400 220606_s_at ADPRM ADP‐ribose/CDP‐alcohol diphosphatase, manganese dependent 6,50E‐06 −1,430 217410_at AGRN agrin 2,34E‐10 1,420 212980_at AHSA2P activator of HSP90 ATPase homolog 2, pseudogene 6,44E‐06 −1,920 219672_at AHSP alpha hemoglobin stabilizing protein 7,27E‐05 2,330 aminoacyl tRNA synthetase complex interacting multifunctional 202541_at AIMP1 4,91E‐06 −1,830 protein 1 210269_s_at AKAP17A A‐kinase anchoring protein 17A 2,64E‐10 −1,560 211560_s_at ALAS2 5ʹ‐aminolevulinate synthase 2 4,28E‐06 3,560 212224_at ALDH1A1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member A1 8,93E‐04 −1,400 205583_s_at ALG13 ALG13 UDP‐N‐acetylglucosaminyltransferase subunit 9,50E‐07 −1,430 207206_s_at ALOX12 arachidonate 12‐lipoxygenase, 12S type 4,76E‐05 1,630 AMY1C (includes 208498_s_at amylase alpha 1C 3,83E‐05 −1,700 others) 201043_s_at ANP32A acidic nuclear phosphoprotein 32 family member A 5,61E‐09 −1,760 202888_s_at ANPEP alanyl aminopeptidase, membrane 7,40E‐04 −1,600 221013_s_at APOL2 apolipoprotein L2 6,57E‐11 1,600 219094_at ARMC8 armadillo repeat containing 8 3,47E‐08 −1,710 207798_s_at ATXN2L ataxin 2 like 2,16E‐07 −1,410 215990_s_at BCL6 BCL6 transcription repressor 1,74E‐07 −1,700 200776_s_at BZW1 basic leucine zipper and W2 domains 1 1,09E‐06 −1,570 222309_at -

Initiation of Antiviral B Cell Immunity Relies on Innate Signals from Spatially Positioned NKT Cells

Initiation of Antiviral B Cell Immunity Relies on Innate Signals from Spatially Positioned NKT Cells The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Gaya, Mauro et al. “Initiation of Antiviral B Cell Immunity Relies on Innate Signals from Spatially Positioned NKT Cells.” Cell 172, 3 (January 2018): 517–533 © 2017 The Author(s) As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.036 Publisher Elsevier Version Final published version Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/113555 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Article Initiation of Antiviral B Cell Immunity Relies on Innate Signals from Spatially Positioned NKT Cells Graphical Abstract Authors Mauro Gaya, Patricia Barral, Marianne Burbage, ..., Andreas Bruckbauer, Jessica Strid, Facundo D. Batista Correspondence [email protected] (M.G.), [email protected] (F.D.B.) In Brief NKT cells are required for the initial formation of germinal centers and production of effective neutralizing antibody responses against viruses. Highlights d NKT cells promote B cell immunity upon viral infection d NKT cells are primed by lymph-node-resident macrophages d NKT cells produce early IL-4 wave at the follicular borders d Early IL-4 wave is required for efficient seeding of germinal centers Gaya et al., 2018, Cell 172, 517–533 January 25, 2018 ª 2017 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.036 Article Initiation of Antiviral B Cell Immunity Relies on Innate Signals from Spatially Positioned NKT Cells Mauro Gaya,1,2,* Patricia Barral,2,3 Marianne Burbage,2 Shweta Aggarwal,2 Beatriz Montaner,2 Andrew Warren Navia,1,4,5 Malika Aid,6 Carlson Tsui,2 Paula Maldonado,2 Usha Nair,1 Khader Ghneim,7 Padraic G. -

Discovery of Rare Variants Associated with Blood Pressure Regulation Through Meta- 2 Analysis of 1.3 Million Individuals 3 4 Praveen Surendran1,2,3,4,266, Elena V

1 Discovery of rare variants associated with blood pressure regulation through meta- 2 analysis of 1.3 million individuals 3 4 Praveen Surendran1,2,3,4,266, Elena V. Feofanova5,266, Najim Lahrouchi6,7,8,266, Ioanna Ntalla9,266, Savita 5 Karthikeyan1,266, James Cook10, Lingyan Chen1, Borbala Mifsud9,11, Chen Yao12,13, Aldi T. Kraja14, James 6 H. Cartwright9, Jacklyn N. Hellwege15, Ayush Giri15,16, Vinicius Tragante17,18, Gudmar Thorleifsson18, 7 Dajiang J. Liu19, Bram P. Prins1, Isobel D. Stewart20, Claudia P. Cabrera9,21, James M. Eales22, Artur 8 Akbarov22, Paul L. Auer23, Lawrence F. Bielak24, Joshua C. Bis25, Vickie S. Braithwaite20,26,27, Jennifer A. 9 Brody25, E. Warwick Daw14, Helen R. Warren9,21, Fotios Drenos28,29, Sune Fallgaard Nielsen30, Jessica D. 10 Faul31, Eric B. Fauman32, Cristiano Fava33,34, Teresa Ferreira35, Christopher N. Foley1,36, Nora 11 Franceschini37, He Gao38,39, Olga Giannakopoulou9,40, Franco Giulianini41, Daniel F. Gudbjartsson18,42, 12 Xiuqing Guo43, Sarah E. Harris44,45, Aki S. Havulinna45,46, Anna Helgadottir18, Jennifer E. Huffman47, Shih- 13 Jen Hwang48,49, Stavroula Kanoni9,50, Jukka Kontto46, Martin G. Larson51,52, Ruifang Li-Gao53, Jaana 14 Lindström46, Luca A. Lotta20, Yingchang Lu54,55, Jian’an Luan20, Anubha Mahajan56,57, Giovanni Malerba58, 15 Nicholas G. D. Masca59,60, Hao Mei61, Cristina Menni62, Dennis O. Mook-Kanamori53,63, David Mosen- 16 Ansorena38, Martina Müller-Nurasyid64,65,66, Guillaume Paré67, Dirk S. Paul1,2,68, Markus Perola46,69, Alaitz 17 Poveda70, Rainer Rauramaa71,72, Melissa Richard73, Tom G. Richardson74, Nuno Sepúlveda75,76, Xueling 18 Sim77,78, Albert V. Smith79,80,81, Jennifer A. -

High Expression of Human Augmincomplex Submit 3 Indicates Poor Prognosis and Associates with Tumor Progression in Hepatocellular

Journal of Cancer 2019, Vol. 10 1434 Ivyspring International Publisher Journal of Cancer 2019; 10(6): 1434-1443. doi: 10.7150/jca.28317 Research Paper High Expression of Human AugminComplex Submit 3 Indicates Poor Prognosis and Associates with Tumor Progression in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Xuanyu Zhang1,2*, Runzhou Zhuang1,2*, Qianwei Ye1,2, Jianyong Zhuo1,2, Kangchen Chen1,2, Di Lu1,2, Xuyong Wei1,2, Haiyang Xie1,2, Xiao Xu1,2, Shusen Zheng1,2 1. Division of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, Department of Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou 310003,China 2. NHFPC Key Laboratory of Combined Multi-organ Transplantation, Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou 310003, China *Xuanyu Zhang and Runzhou Zhang contributed equally to this work. Corresponding authors: Xu Xiao, MD, PhD. Tel: +86-571-87236567; Fax: +86-571-87236567; E-mail: [email protected] and Shusen Zheng, MD, PhD. Tel: +86-571-87236567; Fax: +86-571-87236567; E-mail: [email protected] © Ivyspring International Publisher. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). See http://ivyspring.com/terms for full terms and conditions. Received: 2018.07.05; Accepted: 2019.01.28; Published: 2019.02.23 Abstract The function of human augmin complex unit 3(Haus3), a component of the HAU augmin-like complex, in various cancers is not clear. This study aims to elucidate the clinical significance and the role of Haus3 in tumor progression of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). We analyzed the expression of Haus3 in 50 HCC patients from The Cancer Genome Atlas and 137 HCC patients in our hospital. -

Mutational Evolution in a Lobular Breast Tumour Profiled at Single Nucleotide Resolution

Vol 461 | 8 October 2009 | doi:10.1038/nature08489 LETTERS Mutational evolution in a lobular breast tumour profiled at single nucleotide resolution Sohrab P. Shah1,2*, Ryan D. Morin3*, Jaswinder Khattra1, Leah Prentice1, Trevor Pugh3, Angela Burleigh1, Allen Delaney3, Karen Gelmon4, Ryan Guliany1, Janine Senz2, Christian Steidl2,5, Robert A. Holt3, Steven Jones3, Mark Sun1, Gillian Leung1, Richard Moore3, Tesa Severson3, Greg A. Taylor3, Andrew E. Teschendorff6, Kane Tse1, Gulisa Turashvili1, Richard Varhol3, Rene´ L. Warren3, Peter Watson7, Yongjun Zhao3, Carlos Caldas6, David Huntsman2,5, Martin Hirst3, Marco A. Marra3 & Samuel Aparicio1,2,5 Recent advances in next generation sequencing1–4 have made it coding indels and predicted inversions (coding or non-coding; possible to precisely characterize all somatic coding mutations that Supplementary Methods); however, all of the events that were vali- occur during the development and progression of individual can- dated by Sanger re-sequencing were also present in the germ line cers. Here we used these approaches to sequence the genomes (.43- (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). None of the 12 predicted gene fold coverage) and transcriptomes of an oestrogen-receptor-a- fusions revalidated. We also computed the segmental copy number positive metastatic lobular breast cancer at depth. We found 32 (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table 5a) from aligned somatic non-synonymous coding mutations present in the meta- reads, and revalidated high level amplicons by fluorescence in situ stasis, and measured the frequency of these somatic mutations in hybridization (FISH) (Supplementary Table 5b), revealing the pres- DNA from the primary tumour of the same patient, which arose ence of a new low-level amplicon in the INSR locus (Supplementary 9 years earlier. -

Identification of Novel Fusion Transcripts in High Grade Serous

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Identification of Novel Fusion Transcripts in High Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer Andreea Newtson 1,* , Henry Reyes 2, Eric J. Devor 3,4 , Michael J. Goodheart 1,3 and Jesus Gonzalez Bosquet 1,3 1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA; [email protected] (M.J.G.); [email protected] (J.G.B.) 2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14260, USA; [email protected] 3 Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-319-356-2015 Abstract: Fusion genes are structural chromosomal rearrangements resulting in the exchange of DNA sequences between genes. This results in the formation of a new combined gene. They have been implicated in carcinogenesis in a number of different cancers, though they have been understudied in high grade serous ovarian cancer. This study used high throughput tools to compare the transcrip- tome of high grade serous ovarian cancer and normal fallopian tubes in the interest of identifying unique fusion transcripts within each group. Indeed, we found that there were significantly more fusion transcripts in the cancer samples relative to the normal fallopian tubes. Following this, the Citation: Newtson, A.; Reyes, H.; role of fusion transcripts in chemo-response and overall survival was investigated. This led to the Devor, E.J.; Goodheart, M.J.; Bosquet, identification of fusion transcripts significantly associated with overall survival. -

Howson Edver 1599154836 1

Discovery of rare variants associated with blood pressure regulation through meta-analysis of 1.3 million individuals Praveen Surendran1,2,3,4,266, Elena V. Feofanova5,266, Najim Lahrouchi6,7,8,266, Ioanna Ntalla9,266, Savita Karthikeyan1,266, James Cook10, Lingyan Chen1, Borbala Mifsud9,11, Chen Yao12,13, Aldi T. Kraja14, James H. Cartwright9, Jacklyn N. Hellwege15, Ayush Giri15,16, Vinicius Tragante17,18, Gudmar Thorleifsson18, Dajiang J. Liu19, Bram P. Prins1, Isobel D. Stewart20, Claudia P. Cabrera9,21, James M. Eales22, Artur Akbarov22, Paul L. Auer23, Lawrence F. Bielak24, Joshua C. Bis25, Vickie S. Braithwaite20,26,27, Jennifer A. Brody25, E. Warwick Daw14, Helen R. Warren9,21, Fotios Drenos28,29, Sune Fallgaard Nielsen30, Jessica D. Faul31, Eric B. Fauman32, Cristiano Fava33,34, Teresa Ferreira35, Christopher N. Foley1,36, Nora Franceschini37, He Gao38,39, Olga Giannakopoulou9,40, Franco Giulianini41, Daniel F. Gudbjartsson18,42, Xiuqing Guo43, Sarah E. Harris44,45, Aki S. Havulinna45,46, Anna Helgadottir18, Jennifer E. Huffman47, Shih-Jen Hwang48,49, Stavroula Kanoni9,50, Jukka Kontto46, Martin G. Larson51,52, Ruifang Li-Gao53, Jaana Lindström46, Luca A. Lotta20, Yingchang Lu54,55, Jian’an Luan20, Anubha Mahajan56,57, Giovanni Malerba58, Nicholas G. D. Masca59,60, Hao Mei61, Cristina Menni62, Dennis O. Mook-Kanamori53,63, David Mosen-Ansorena38, Martina Müller-Nurasyid64,65,66, Guillaume Paré67, Dirk S. Paul1,2,68, Markus Perola46,69, Alaitz Poveda70, Rainer Rauramaa71,72, Melissa Richard73, Tom G. Richardson74, Nuno Sepúlveda75,76, Xueling Sim77,78, Albert V. Smith79,80,81, Jennifer A. Smith24,31, James R. Staley1,74, Alena Stanáková82, Patrick Sulem18, Sébastien Thériault83,84, Unnur Thorsteinsdottir18,80, Stella Trompet85,86, Tibor V.