Identification of Novel Fusion Transcripts in High Grade Serous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

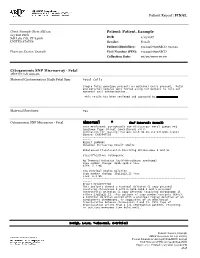

Cytogenomic SNP Microarray - Fetal ARUP Test Code 2002366 Maternal Contamination Study Fetal Spec Fetal Cells

Patient Report |FINAL Client: Example Client ABC123 Patient: Patient, Example 123 Test Drive Salt Lake City, UT 84108 DOB 2/13/1987 UNITED STATES Gender: Female Patient Identifiers: 01234567890ABCD, 012345 Physician: Doctor, Example Visit Number (FIN): 01234567890ABCD Collection Date: 00/00/0000 00:00 Cytogenomic SNP Microarray - Fetal ARUP test code 2002366 Maternal Contamination Study Fetal Spec Fetal Cells Single fetal genotype present; no maternal cells present. Fetal and maternal samples were tested using STR markers to rule out maternal cell contamination. This result has been reviewed and approved by Maternal Specimen Yes Cytogenomic SNP Microarray - Fetal Abnormal * (Ref Interval: Normal) Test Performed: Cytogenomic SNP Microarray- Fetal (ARRAY FE) Specimen Type: Direct (uncultured) villi Indication for Testing: Patient with 46,XX,t(4;13)(p16.3;q12) (Quest: EN935475D) ----------------------------------------------------------------- ----- RESULT SUMMARY Abnormal Microarray Result (Male) Unbalanced Translocation Involving Chromosomes 4 and 13 Classification: Pathogenic 4p Terminal Deletion (Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome) Copy number change: 4p16.3p16.2 loss Size: 5.1 Mb 13q Proximal Region Deletion Copy number change: 13q11q12.12 loss Size: 6.1 Mb ----------------------------------------------------------------- ----- RESULT DESCRIPTION This analysis showed a terminal deletion (1 copy present) involving chromosome 4 within 4p16.3p16.2 and a proximal interstitial deletion (1 copy present) involving chromosome 13 within 13q11q12.12. This -

A Genome-Wide Association Study of Bisphosphonate-Associated

Calcifed Tissue International (2019) 105:51–67 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-019-00546-9 ORIGINAL RESEARCH A Genome‑Wide Association Study of Bisphosphonate‑Associated Atypical Femoral Fracture Mohammad Kharazmi1 · Karl Michaëlsson1 · Jörg Schilcher2 · Niclas Eriksson3,4 · Håkan Melhus3 · Mia Wadelius3 · Pär Hallberg3 Received: 8 January 2019 / Accepted: 8 April 2019 / Published online: 20 April 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Atypical femoral fracture is a well-documented adverse reaction to bisphosphonates. It is strongly related to duration of bisphosphonate use, and the risk declines rapidly after drug withdrawal. The mechanism behind bisphosphonate-associated atypical femoral fracture is unclear, but a genetic predisposition has been suggested. With the aim to identify common genetic variants that could be used for preemptive genetic testing, we performed a genome-wide association study. Cases were recruited mainly through reports of adverse drug reactions sent to the Swedish Medical Products Agency on a nation- wide basis. We compared atypical femoral fracture cases (n = 51) with population-based controls (n = 4891), and to reduce the possibility of confounding by indication, we also compared with bisphosphonate-treated controls without a current diagnosis of cancer (n = 324). The total number of single-nucleotide polymorphisms after imputation was 7,585,874. A genome-wide signifcance threshold of p < 5 × 10−8 was used to correct for multiple testing. In addition, we performed candidate gene analyses for a panel of 29 genes previously implicated in atypical femoral fractures (signifcance threshold of p < 5.7 × 10−6). Compared with population controls, bisphosphonate-associated atypical femoral fracture was associated with four isolated, uncommon single-nucleotide polymorphisms. -

Species-Specific Difference in Expression and Splice-Site Choice In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Mamm Genome (2010) 21:458–466 DOI 10.1007/s00335-010-9281-7 Species-specific difference in expression and splice-site choice in Inpp5b, an inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase paralogous to the enzyme deficient in Lowe Syndrome Susan P. Bothwell • Leslie W. Farber • Adam Hoagland • Robert L. Nussbaum Received: 11 June 2010 / Accepted: 31 August 2010 / Published online: 26 September 2010 Ó The Author(s) 2010. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract The oculocerebrorenal syndrome of Lowe Inpp5b/INPP5B are the most highly conserved paralogs to (OCRL; MIM #309000) is an X-linked human disorder Ocrl/OCRL in the respective genomes of both species and characterized by congenital cataracts, mental retardation, Inpp5b demonstrates functional overlap with Ocrl in mice and renal proximal tubular dysfunction caused by loss-of- in vivo. We used in silico sequence analysis, reverse-tran- function mutations in the OCRL gene that encodes Ocrl, a scription PCR, quantitative PCR, and transient transfection type II phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate (PtdIns4,5P2) assays of promoter function to define splice-site usage and 5-phosphatase. In contrast, mice with complete loss-of- the function of an internal promoter in mouse Inpp5b function of the highly homologous ortholog Ocrl have no versus human INPP5B. We found mouse Inpp5b and detectable renal, ophthalmological, or central nervous human INPP5B differ in their transcription, splicing, and system abnormalities. We inferred that the disparate phe- primary amino acid sequence. These observations form the notype between Ocrl-deficient humans and mice was likely foundation for analyzing the functional basis for the dif- due to differences in how the two species compensate for ference in how Inpp5b and INPP5B compensate for loss of loss of the Ocrl enzyme. -

Prioritization and Evaluation of Depression Candidate Genes by Combining Multidimensional Data Resources

Prioritization and Evaluation of Depression Candidate Genes by Combining Multidimensional Data Resources Chung-Feng Kao1, Yu-Sheng Fang2, Zhongming Zhao3, Po-Hsiu Kuo1,2,4* 1 Department of Public Health and Institute of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan, 2 Institute of Clinical Medicine, School of Medicine, National Cheng-Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, 3 Departments of Biomedical Informatics and Psychiatry, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee, United States of America, 4 Research Center for Genes, Environment and Human Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan Abstract Background: Large scale and individual genetic studies have suggested numerous susceptible genes for depression in the past decade without conclusive results. There is a strong need to review and integrate multi-dimensional data for follow up validation. The present study aimed to apply prioritization procedures to build-up an evidence-based candidate genes dataset for depression. Methods: Depression candidate genes were collected in human and animal studies across various data resources. Each gene was scored according to its magnitude of evidence related to depression and was multiplied by a source-specific weight to form a combined score measure. All genes were evaluated through a prioritization system to obtain an optimal weight matrix to rank their relative importance with depression using the combined scores. The resulting candidate gene list for depression (DEPgenes) was further evaluated by a genome-wide association (GWA) dataset and microarray gene expression in human tissues. Results: A total of 5,055 candidate genes (4,850 genes from human and 387 genes from animal studies with 182 being overlapped) were included from seven data sources. -

Influencers on Thyroid Cancer Onset: Molecular Genetic Basis

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review Influencers on Thyroid Cancer Onset: Molecular Genetic Basis Berta Luzón-Toro 1,2, Raquel María Fernández 1,2, Leticia Villalba-Benito 1,2, Ana Torroglosa 1,2, Guillermo Antiñolo 1,2 and Salud Borrego 1,2,* 1 Department of Maternofetal Medicine, Genetics and Reproduction, Institute of Biomedicine of Seville (IBIS), University Hospital Virgen del Rocío/CSIC/University of Seville, 41013 Seville, Spain; [email protected] (B.L.-T.); [email protected] (R.M.F.); [email protected] (L.V.-B.); [email protected] (A.T.); [email protected] (G.A.) 2 Centre for Biomedical Network Research on Rare Diseases (CIBERER), 41013 Seville, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-955-012641 Received: 3 September 2019; Accepted: 6 November 2019; Published: 8 November 2019 Abstract: Thyroid cancer, a cancerous tumor or growth located within the thyroid gland, is the most common endocrine cancer. It is one of the few cancers whereby incidence rates have increased in recent years. It occurs in all age groups, from children through to seniors. Most studies are focused on dissecting its genetic basis, since our current knowledge of the genetic background of the different forms of thyroid cancer is far from complete, which poses a challenge for diagnosis and prognosis of the disease. In this review, we describe prevailing advances and update our understanding of the molecular genetics of thyroid cancer, focusing on the main genes related with the pathology, including the different noncoding RNAs associated with the disease. -

Genome-Wide Analysis of Host-Chromosome Binding Sites For

Lu et al. Virology Journal 2010, 7:262 http://www.virologyj.com/content/7/1/262 RESEARCH Open Access Genome-wide analysis of host-chromosome binding sites for Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 1 (EBNA1) Fang Lu1, Priyankara Wikramasinghe1, Julie Norseen1,2, Kevin Tsai1, Pu Wang1, Louise Showe1, Ramana V Davuluri1, Paul M Lieberman1* Abstract The Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) Nuclear Antigen 1 (EBNA1) protein is required for the establishment of EBV latent infection in proliferating B-lymphocytes. EBNA1 is a multifunctional DNA-binding protein that stimulates DNA replication at the viral origin of plasmid replication (OriP), regulates transcription of viral and cellular genes, and tethers the viral episome to the cellular chromosome. EBNA1 also provides a survival function to B-lymphocytes, potentially through its ability to alter cellular gene expression. To better understand these various functions of EBNA1, we performed a genome-wide analysis of the viral and cellular DNA sites associated with EBNA1 protein in a latently infected Burkitt lymphoma B-cell line. Chromatin-immunoprecipitation (ChIP) combined with massively parallel deep-sequencing (ChIP-Seq) was used to identify cellular sites bound by EBNA1. Sites identified by ChIP- Seq were validated by conventional real-time PCR, and ChIP-Seq provided quantitative, high-resolution detection of the known EBNA1 binding sites on the EBV genome at OriP and Qp. We identified at least one cluster of unusually high-affinity EBNA1 binding sites on chromosome 11, between the divergent FAM55 D and FAM55B genes. A con- sensus for all cellular EBNA1 binding sites is distinct from those derived from the known viral binding sites, sug- gesting that some of these sites are indirectly bound by EBNA1. -

Regular Article

Regular Article MYELOID NEOPLASIA Potent inhibition of DOT1L as treatment of MLL-fusion leukemia Scott R. Daigle, Edward J. Olhava, Carly A. Therkelsen, Aravind Basavapathruni, Lei Jin, P. Ann Boriack-Sjodin, Christina J. Allain, Christine R. Klaus, Alejandra Raimondi, Margaret Porter Scott, Nigel J. Waters, Richard Chesworth, Mikel P. Moyer, Robert A. Copeland, Victoria M. Richon, and Roy M. Pollock Epizyme, Inc., Cambridge, MA Key Points Rearrangements of the MLL gene define a genetically distinct subset of acute leukemias with poor prognosis. Current treatment options are of limited effectiveness; thus, there • EPZ-5676 is a potent DOT1L is a pressing need for new therapies for this disease. Genetic and small molecule inhibitor inhibitor that causes tumor studies have demonstrated that the histone methyltransferase DOT1L is required for regressions in a rat xenograft the development and maintenance of MLL-rearranged leukemia in model systems. Here model of MLL-rearranged we describe the characterization of EPZ-5676, a potent and selective aminonucleoside leukemia. inhibitor of DOT1L histone methyltransferase activity. The compound has an inhibition constant value of 80 pM, and demonstrates 37 000-fold selectivity over all other methyltransferases tested. In cellular studies, EPZ-5676 inhibited H3K79 methylation and MLL-fusion target gene expression and demonstrated potent cell killing that was selective for acute leukemia lines bearing MLL translocations. Continuous IV infusion of EPZ-5676 in a rat xenograft model of MLL-rearranged leukemia caused complete tumor regressions that were sustained well beyond the compound infusion period with no significant weight loss or signs of toxicity. EPZ-5676 is therefore a potential treatment of MLL-rearranged leukemia and is under clinical investigation. -

The Histone Methyltransferase DOT1L Prevents Antigen-Independent

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/826255; this version posted November 18, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. The histone methyltransferase DOT1L prevents antigen-independent differentiation and safeguards epigenetic identity of CD8+ T cells Eliza Mari Kwesi-Maliepaard1*, Muhammad Assad Aslam2,3*, Mir Farshid Alemdehy2*, Teun van den Brand4, Chelsea McLean1, Hanneke Vlaming1, Tibor van Welsem1, Tessy Korthout1, Cesare Lancini1, Sjoerd Hendriks1, Tomasz Ahrends5, Dieke van Dinther6, Joke M.M. den Haan6, Jannie Borst5, Elzo de Wit4, Fred van Leeuwen1,7,#, and Heinz Jacobs2,# 1Division of Gene Regulation, Netherlands Cancer Institute, 1066CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2Division of Tumor Biology & Immunology, Netherlands Cancer Institute, 1066CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands 3Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, Bahauddin Zakariya University, 60800 Multan, Pakistan 4Division of Gene Regulation, Netherlands Cancer Institute, 1066CX Amsterdam, and Oncode Institute, The Netherlands 5Division of Tumor Biology & Immunology, Netherlands Cancer Institute, 1066CX Amsterdam, and Oncode Institute, The Netherlands 6Department of Molecular Cell Biology and Immunology, Amsterdam UMC, Location VUmc, 1081HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands 7Department of Medical Biology, Amsterdam UMC, location AMC, UvA, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands * These authors contributed equally to this work. # Equal contribution and corresponding authors [email protected]; [email protected] Lead contact: Fred van Leeuwen 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/826255; this version posted November 18, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Building Bonds Between NHGRI and NICHD • NICHD Has Four ABMGG Boarded Clinical Geneticists • Drs

Building Bonds Between NHGRI NICHD Diana W. Bianchi, M.D. Director, NICHD November 8, 2017 A Vision for NICHD’s Future What’s In a Name? NICHD 18% Other Institutes 82% Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development History of Our Mission ". We will look to the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development for a concentrated attack on the unsolved health problems of children and of mother-infant relationships. This legislation will encourage imaginative research into the complex processes of human development from conception to old age. For the first time, we will have an institute to promote studies directed at the entire life process rather than toward specific diseases or illnesses." —John F. Kennedy, October 17, 1962 My Vision for NICHD-I • Define “our brand” (what is our focus?) • Communicate the message • Listen to the Voice of the Patient • Integrate obstetrics and pediatrics research at NICHD; take the long view (DoHaD) • Advocate for personalized medicine in pediatrics, obstetrics and rehabilitative medicine My Vision for NICHD-II • Stress the importance of data science and sharing to leverage our investments • Analyze best way to identify trainees most likely to succeed • Catalyze innovation • Emphasize the “A” (for “Advice”) in the Advisory Council • Build bridges between other NIH Institutes – especially with NHGRI Ensure Representation of NICHD Populations in Trans-NIH Initiatives • Pregnant women can be enrolled in Phase I • Adults with intellectual disabilities can be enrolled once consent issues have been clarified • Children to be enrolled in Phase II Building Bonds Melissa Parisi MD PhD Medical Genetics Branch: Prenatal Genomics and Therapy Section • New Lab at NHGRI • Focus on Prenatal Treatment of Down syndrome • Incidental Findings Following Prenatal DNA Screening Building Bonds Between NHGRI and NICHD • NICHD has four ABMGG boarded clinical geneticists • Drs. -

List of Genes Associated with Sudden Cardiac Death (Scdgseta) Gene

List of genes associated with sudden cardiac death (SCDgseta) mRNA expression in normal human heart Entrez_I Gene symbol Gene name Uniprot ID Uniprot name fromb D GTEx BioGPS SAGE c d e ATP-binding cassette subfamily B ABCB1 P08183 MDR1_HUMAN 5243 √ √ member 1 ATP-binding cassette subfamily C ABCC9 O60706 ABCC9_HUMAN 10060 √ √ member 9 ACE Angiotensin I–converting enzyme P12821 ACE_HUMAN 1636 √ √ ACE2 Angiotensin I–converting enzyme 2 Q9BYF1 ACE2_HUMAN 59272 √ √ Acetylcholinesterase (Cartwright ACHE P22303 ACES_HUMAN 43 √ √ blood group) ACTC1 Actin, alpha, cardiac muscle 1 P68032 ACTC_HUMAN 70 √ √ ACTN2 Actinin alpha 2 P35609 ACTN2_HUMAN 88 √ √ √ ACTN4 Actinin alpha 4 O43707 ACTN4_HUMAN 81 √ √ √ ADRA2B Adrenoceptor alpha 2B P18089 ADA2B_HUMAN 151 √ √ AGT Angiotensinogen P01019 ANGT_HUMAN 183 √ √ √ AGTR1 Angiotensin II receptor type 1 P30556 AGTR1_HUMAN 185 √ √ AGTR2 Angiotensin II receptor type 2 P50052 AGTR2_HUMAN 186 √ √ AKAP9 A-kinase anchoring protein 9 Q99996 AKAP9_HUMAN 10142 √ √ √ ANK2/ANKB/ANKYRI Ankyrin 2 Q01484 ANK2_HUMAN 287 √ √ √ N B ANKRD1 Ankyrin repeat domain 1 Q15327 ANKR1_HUMAN 27063 √ √ √ ANKRD9 Ankyrin repeat domain 9 Q96BM1 ANKR9_HUMAN 122416 √ √ ARHGAP24 Rho GTPase–activating protein 24 Q8N264 RHG24_HUMAN 83478 √ √ ATPase Na+/K+–transporting ATP1B1 P05026 AT1B1_HUMAN 481 √ √ √ subunit beta 1 ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic ATP2A2 P16615 AT2A2_HUMAN 488 √ √ √ reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 AZIN1 Antizyme inhibitor 1 O14977 AZIN1_HUMAN 51582 √ √ √ UDP-GlcNAc: betaGal B3GNT7 beta-1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransfe Q8NFL0 -

Evidence for Differential Alternative Splicing in Blood of Young Boys With

Stamova et al. Molecular Autism 2013, 4:30 http://www.molecularautism.com/content/4/1/30 RESEARCH Open Access Evidence for differential alternative splicing in blood of young boys with autism spectrum disorders Boryana S Stamova1,2,5*, Yingfang Tian1,2,4, Christine W Nordahl1,3, Mark D Shen1,3, Sally Rogers1,3, David G Amaral1,3 and Frank R Sharp1,2 Abstract Background: Since RNA expression differences have been reported in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) for blood and brain, and differential alternative splicing (DAS) has been reported in ASD brains, we determined if there was DAS in blood mRNA of ASD subjects compared to typically developing (TD) controls, as well as in ASD subgroups related to cerebral volume. Methods: RNA from blood was processed on whole genome exon arrays for 2-4–year-old ASD and TD boys. An ANCOVA with age and batch as covariates was used to predict DAS for ALL ASD (n=30), ASD with normal total cerebral volumes (NTCV), and ASD with large total cerebral volumes (LTCV) compared to TD controls (n=20). Results: A total of 53 genes were predicted to have DAS for ALL ASD versus TD, 169 genes for ASD_NTCV versus TD, 1 gene for ASD_LTCV versus TD, and 27 genes for ASD_LTCV versus ASD_NTCV. These differences were significant at P <0.05 after false discovery rate corrections for multiple comparisons (FDR <5% false positives). A number of the genes predicted to have DAS in ASD are known to regulate DAS (SFPQ, SRPK1, SRSF11, SRSF2IP, FUS, LSM14A). In addition, a number of genes with predicted DAS are involved in pathways implicated in previous ASD studies, such as ROS monocyte/macrophage, Natural Killer Cell, mTOR, and NGF signaling. -

Full-Length Cdna, Expression Pattern and Association Analysis of the Porcine FHL3 Gene

1473 Asian-Aust. J. Anim. Sci. Vol. 20, No. 10 : 1473 - 1477 October 2007 www.ajas.info Full-length cDNA, Expression Pattern and Association Analysis of the Porcine FHL3 Gene Bo Zuo*, YuanZhu Xiong, Hua Yang and Jun Wang Key Laboratory of Swine Genetics and Breeding, Ministry of Agriculture & Key Lab of Agricultural Animal Genetics, Breeding and Reproduction, Ministry of Education, College of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, 430070, P. R. China ABSTRACT : Four-and-a-half LIM-only protein 3 (FHL3) is a member of the LIM protein superfamily and can participate in mediating protein-protein interaction by binding one another through their LIM domains. In this study, the 5'- and 3'- cDNA ends were characterized by RACE (Rapid Amplification of the cDNA Ends) methodology in combination with in silica cloning based on the partial cDNA sequence obtained. Bioinformatics analysis showed FHL3 protein contained four LIM domains and four LIM zinc-binding domains. In silica mapping assigned this gene to the gene cluster MTF1-INPP5B-SF3A3-FHL3-CGI-94 on pig chromosome 6 where several QTL affecting intramuscular fat and eye muscle area had previously been identified. Transcription of the FHL3 gene was detected in spleen, liver, kidney, small intestine, skeletal muscle, fat and stomach, with the greatest expression in skeletal muscle. The A/G polymorphism in exon II was significantly associated with birth weight, average daily gain before weaning, drip loss rate, water holding capacity and intramuscular fat in a Landrace-derived pig population. Together, the present study provided the useful information for further studies to determine the roles of FHL3 gene in the regulation of skeletal muscle cell growth and differentiation in pigs.