Catherine Cartwright's Account of Labrador Inuit in England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BXAO Cat 1971.Pdf

SOUTHWESTERN AT OXFORD Britain in the Renaissance A Course of Studies in the Arts, Literature, History, and Philosophy of Great Britain. July 4 through August 15, 1971, University College, Oxford University. OFFICERS AND TUTORS President John Henry Davis, A.B., University of Kentucky; B.A. and M.A., Oxford University; Ph.D., University of Chicago. Dean Yerger Hunt Clifton, B.A., Duke University; M.A., University of Virginia; Ph.D., Trinity College, Dublin. Tutors George Marshall Apperson, Jr., B.S., Davidson College; B.D., Th.M., Th.D., Union Theological Seminary, Virginia. Mary Ross Burkhart, B.A., University of Virginia; M.A., University of Ten nessee. James William Jobes, B.A., St. John's College, Annapolis; Ph.D., University of Virginia. James Edgar Roper, B.A., Southwestern At Memphis; B.A. and M.A., Oxford University; M.A., Yale University. UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, OXFORD UNIVERSITY Master Redcliffe-Maud of Bristol, The Right Honorourable John Primatt Redcliffe, Baron, M.A. Dean John Leslie Mackie, M.A. Librarian Peter Charles Bayley, M.A. Chaplain David John Burgess, M.A. Domestic Bursar Vice Admiral Sir Peter William Gretton, M.A. University College is officially a Royal Foundation, and the Sovereign is its Visitor. Its right to this dignity, based on medieval claims that it was founded by King Alfred the Great, has twice been asserted, by King Richard II in 1380 and by the Court of King's Bench in 1726. In fact, the college owes its origin to William of Durham who died in 1249 and bequeathed 310 marks, the income from which was to be employed to maintain 10 or more needy Masters of Arts studying divinity. -

HISTORY of REVOLUTIONS and ERA of COLONIALISM (2014 Admission Onwards)

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION III SEMESTER B.A HISTORY: COMPLEMENTARY SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN: HIS3C03 HISTORY OF REVOLUTIONS AND ERA OF COLONIALISM (2014 Admission onwards) Multiple-Choice Questions and Answers Prepared by Dr.N.PADMANABHAN Associate Professor&Head P.G.Department of History C.A.S.College, Madayi P.O.Payangadi-RS-670358 Dt.Kannur-Kerala 0 1. The Glorious Revolution is the name given to a series of events that took place in the late 17th century in................... a) England b) France c) America d) Holland 2. Through the Restoration, ………………became the king of England. a) Charles II b) Robert Owen c)James I d)James II 3……………….., an avowed Catholic and believer of the Devine Right, like previous Stuart kings, came into throne in 1685. a) James II b) Robert Owen c) John Russell d) ) Charles II 4. In………………., a revolution without bloodshed took place against James II’s activities. a) 1688 b)1693 c)1694 d)1697 5.The main cause behind the Glorious revolution was ………………attempt to revive Catholicism in England. a) James II’s b) Robert Owens c) John Russell’s d) Charles II’s 6.In 1686, …………….founded the “Court of Ecclesiastical Commission” like previous ‘High Commission Court’ (cancelled in 1641) in order to punish the people, opposite to his religious doctrine. a) James II b)Sir Isaac Newton c) Elias Howe d) Thomas Edison 7.In 1687, …………….issued the first ‘Declaration of Indulgence’ suspending the penal laws against both Catholics and Dissenters. a) James II b)G.M. -

A Reappraisal Using a Composite Indicator of Patent Quality∗

Patterns of Innovation during the Industrial Revolution: a Reappraisal using a Composite Indicator of Patent Quality∗ Alessandro Nuvolari†a, Valentina Tartarib, and Matteo Trancheroc aScuola Superiore Sant'Anna, Pisa, Italy bCopenhagen Business School, Copenhagen, Denmark cHaas School of Business, UC Berkeley, USA August 5, 2019 Abstract We introduce a new bibliographic quality indicator for English patents granted in the period 1700-1850. The indicator is based on the visibility of each patent both in the contemporary legal and engineering literature and in modern authoritative works on the history of science and technology. The indicator permits to operationalize empirically the distinction between micro- and macroinventions. Our findings indicate that macroinventions did not exhibit any specific time clustering, while at the same time they were characterized by a labor-saving bias. These results suggest that Mokyr's and Allen's views of macroinventions, rather than conflicting, should be regarded as complementary. Keywords: Industrial Revolution; Patents; Macroinventions; Microinventions. JEL Code: N74, O31 ∗Acknowledgements: The authors want to thank Bart Verspagen, Tania Treibich, Abhishek Nagaraj, Sameer Srivas- tava, as well as participants to seminars at University C^oted'Azur, UNU-MERIT, Berkeley-Haas and to EMAEE 2019 at SPRU - University of Sussex for their helpful comments. We are indebted to Joel Mokyr, Ralf Meisenzahl, Morgane Louenan, Olivier Gergaud and Etienne Wasmer for sharing their data. The usual disclaimers apply. †Corresponding author: Alessandro Nuvolari, Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna, Pisa, Italy. Postal address: c/o Institute of Economics, Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna, Piazza Martiri 33, 56127, Pisa, Italy. E-mail: [email protected]. 1 1 Introduction Technical change has traditionally occupied a central place in the historiography of the Indus- trial Revolution. -

Appendix 3-3.Pdf

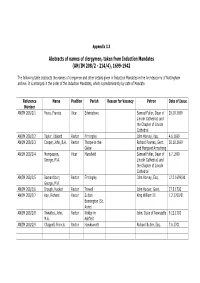

Appendix 3.3 Abstracts of names of clergymen, taken from Induction Mandates (AN/IM 208/2 - 214/4), 1699-1942 The following table abstracts the names of clergymen and other details given in Induction Mandates in the Archdeaconry of Nottingham archive. It is arranged in the order of the Induction Mandates, which is predominantly by date of Mandate. Reference Name Position Parish Reason for Vacancy Patron Date of Issue Number AN/IM 208/2/1 Peete, Francis Vicar Edwinstowe Samuel Fuller, Dean of 26.10.1699 Lincoln Cathedral, and the Chapter of Lincoln Cathedral AN/IM 208/2/2 Taylor, Edward Rector Finningley John Harvey, Esq. 4.6.1699 AN/IM 208/2/3 Cooper, John, B.A. Rector Thorpe-in-the- Richard Fownes, Gent. 30.10.1699 Glebe and Margaret Armstrong AN/IM 208/2/4 Mompesson, Vicar Mansfield Samuel Fuller, Dean of 6.7.1699 George, M.A. Lincoln Cathedral, and the Chapter of Lincoln Cathedral AN/IM 208/2/5 Barnardiston, Rector Finningley John Harvey, Esq. 12.2.1699/00 George, M.A. AN/IM 208/2/6 Brough, Hacker Rector Trowell John Hacker, Gent. 27.5.1700 AN/IM 208/2/7 Kay, Richard Rector Sutton King William III 7.2.1700/01 Bonnington (St. Anne) AN/IM 208/2/8 Thwaites, John, Rector Kirkby-in- John, Duke of Newcastle 9.12.1700 M.A. Ashfield AN/IM 208/2/9 Chappell, Francis Rector Hawksworth Richard Butler, Esq. 7.6.1701 Reference Name Position Parish Reason for Vacancy Patron Date of Issue Number AN/IM 208/2/10 Caiton, William, Vicar Flintham Death of Simon Richard Bentley, Master 15.6.1701 M.A. -

A Short History of the Church of Saint Mary the Virgin, Battle

A Short History of the Church of Saint Mary the Virgin, Battle After the foundation of Battle Abbey the town of Battle grew around it, at first servicing the abbey, finally obtaining its own momentum to grow even bigger. There was a need for markets, forges, tanneries, shoemakers, bakers, masons, farmers and every other trade. The spiritual needs of the population would at first have been provided by the abbey. At first the abbey would have shared its church with the people, but as Battle grew larger the increasing numbers of thronging the nave would have interfered with the abbey's religious purpose as a Benedictine monastery. So the abbey started building a chapel for the town sometime between 1102 and 1107. The monks, during the inter-abbacy of 1102-1107 or otherwise abbot Ralph immediately after his appointment in 1107 would have taken the active decision to provide the townsfolk with their own church building. The monks would have serviced the church at first but in 1115 a priest Humphridus, was appointed by the abbot to be their vicar. We even know where Humphridus lived, which was the 89th messuage belonging to the abbey estate, three properties to the east of St Mary's in the borough of Sandlake1 (on the north side of the present Upper Lake). The priest was expected to pay seven pence per year for this dwelling and also provide at least one day’s labour. From this point (1115) forwards, according to the Chronicle of Battle Abbey (CBA), the chaplain of St Mary's Church was a secular priest and not a monk. -

The Power Loom Puzzle

4 The Power Loom Puzzle The Industrial Revolution was heralded by a flood of inventions and the accumulation of capital which, in new forms, constituted enormous power with which to produce wealth. Innovation was in the air. People were searching for new ways of producing goods at cheaper cost. The conveyor belt was born. Mass production based on the division of labour and the use of mechanical power could have raised the living standards of everybody. Sadly, for the workers, this was not to be: • . without the increase in productive power that is due to industrialization the rise in real wages could not possibly have occurred. The important question is why it was so long delayed. There is no doubt at all that it was delayed; whether there was a small rise, or an actual fall, in the general level of real wages in England between (say) 1780 and 1840 leaves that issue untouched It is the lag of wages behind industrialization which is the thing that has to be explained.' Explanations for this have been partial and none have taken into account the regressive effect of land monopoly. The Marxist critique has conditioned us to believe that capital and the motives of its owners constitute the problematic area. The acquisitive greed of the capitalists is held to be responsible for large- scale poverty and deprivation. From the outset the modern factory system has been blamed. Men had been severed from a tranquil, pastoral history and the machine was nominated as Enemy No. 1. Yet this was ironical, for the machine was as much a victim of the early years of industrial society as were the men. -

English Cotton Textile Production from John Kay (1733)

The Precocious Mechanization of a Global History: English Cotton Textile Production from John Kay (1733) to Richard Roberts (1822)* Patrick Karl O’Brien ‘Dining in a public room, Cartwright became deeply interested in a conversation which was started on the subject of the remarkable inventions of Arkwright and others, and that the consequent extension of manufactures in the neighbourhood and throughout the country. It was urged, however, by one gentleman that Arkwright’s cotton-spinning machinery was not an unmixed blessing, seeing that we should soon be making more yarn than our weaver could work up, with the result that it would have to be largely exported to the Continent, and might there be woven into cloth so cheaply as greatly to injure the English trade. At this point, Dr Cartwright ventured the remark that the only remedy for such evil would be to apply the power of machinery to the art of weaving as well as to that of spinning. The notion was set down as absurd; some Manchester gentlemen, who were presumed to have special knowledge of the subject, being more emphatic in its condemnation, contending that such a contrivance was impossible, on account of the variety and intricacy of the movements in weaving. Against this Cartwright instanced the automaton chess-player, a curiosity then attracting much attention, and argued that a skilful application of mechanism could surmount every difficulty. They were not convinced, but he was; and when he returned home he could think of nothing else. After much brooding, he bent all his energies to the task of constructing the model of a power-loom, working incessantly in his rough and awkward way for several months, but steadily improving step by step, until at last, in April 1785, he took out a patent for the first of all power-looms.’ Margaret Strickland, A Memoir of the Life, Writings and Inventions of Edmund Cartwright (ed. -

Lecture 8 the Industrial Revolution and the Transformation to The

GEOS 24705 ENST 24705 ENSC 21100 Lecture 8 The Industrial Revolution and the transformation to the modern energy system Copyright E. Moyer 2016 Most of U.S. energy use is lost as waste heat total e ~ 40% 70% through transportaon e ~ 21% heat engine turbines e ~ 24% Carnot-style “air engines” are in use • gas only • closed cycle • external combus/on Themes for today • The Industrial Revolu/on and the development of heat engines are related but not the same – industrializaon started before the heat engine – the heat engine ul/mately allowed greater industrializaon • Industrializaon produced profound social & economic upheaval • The upheaval was amplified by limitaons in energy technology Mills had been mechanized and centralized since Medieval times Grindstone, 1700s, U.S. Yates gristmill, North Carolina U.S. from Hamilton, “The Village Mill in Early New England” Mills had been mechanized and centralized since Medieval times Grindstone, 1700s, U.S. Rock Run gristmill, Maryland U.S. from Hamilton, “The Village Mill in Early New England” Textiles were still a home industry in the mid-1770s but extremely repetitive motions are well suited to mechanization Jersey Spinning Wheel. From: The Story of Source: unknown the Cotton Plant, Frederick Wilkinson, 1912, via Gutenberg.org over 6 spinnners to make thread for 1 weaver as looms improved in 1730s Spinning was mechanized to meet thread demand Spinning jenny, 1764 James Hargreaves power: human Spinning mule, 1779 Samuel Crompton Power: water “Water frame” 1769 fully automated by 1830 John Kay, Richard Arkwright power: horses, then water Mechanization of spinning benefits weavers... from Radcliffe on weaving, 1828... -

Mc:Pr30 the Papers of Martin Joseph Routh (D. 1771–5; F

MC:PR30 THE PAPERS OF MARTIN JOSEPH ROUTH (D. 1771–5; F. 1775–91; P. 1791–1854) Catalogued by Robin Darwall-Smith December 2015 Magdalen College Oxford MAGDALEN COLLEGE OXFORD i MC:PR30 PAPERS OF MARTIN ROUTH (D. 1771–5; F. 1775–91; P. 1791–1854) CONTENTS Introduction ii 1 - The life and career of Martin Routh ii 2 - Select bibliography of the works of Martin Routh iii 3 - The history of the present collection iii 4 - Bibliography of works about Martin Routh iv MC:PR30/1: Routh papers collected by John Bloxam 1 MC:PR30/1/C1: Letters concerning Routh’s family and personal life 1 MC:PR30/1/C2: Letters from members of Magdalen College 22 MC:PR30/1/C3: Letters concerning particular individuals or groups of people 130 MC:PR30/1/C4: Letters from miscellaneous correspondents 203 MC:PR30/1/MS1: Material concerning Richard Chandler’s life of William Waynflete 289 MC:PR30/1/MS2: Material concerning Routh’s research 295 MC:PR30/1/MS3: Material concerning Routh’s activities as President 299 MC:PR30/1/MS4: Inscriptions composed by Routh 303 MC:PR30/2: Documents from and concerning Routh’s Library 309 MC:PR30/2/MS1: MS Books from the Routh Library 309 MC:PR30/2/MS2: Catalogues of the Routh Library 312 MC:PR30/3: Documents relating to Routh’s scholarly research 312 MC:PR30/3/MS1: Documents relating to Reliquiae Sacrae 312 MC:PR30/3/MS2: Documents relating to Gilbert Burnet’s memoirs 313 MC:PR30/4: Routh Papers found in Magdalen after Bloxam 313 MC:PR30/4/C1: Letters, mainly concerning Routh’s family 314 MC:PR30/4/C2: Letters on Routh’s dealings with College Visitors 318 MC:PR30/4/C3: Miscellaneous correspondence 322 MC:PR30/4/MS1: Papers on South Petherwyn (now Petherwin) 324 MC:PR30/4/MS2: Miscellaneous Papers 326 MC:PR30/4/N1: Printed Miscellanea 328 MC:PR30/4/P1: Daguerreotype 328 MAGDALEN COLLEGE OXFORD ii MC:PR30 PAPERS OF MARTIN ROUTH (D. -

The Hand-Loom Weaver and the Power Loom: a Schumpeterian Perspective

The Hand-Loom Weaver and the Power Loom: A Schumpeterian Perspective Robert C. Allen Working Paper # 0004 May 2017 Division of Social Science Working Paper Series New York University Abu Dhabi, Saadiyat Island P.O Box 129188, Abu Dhabi, UAE https://nyuad.nyu.edu/en/academics/divisions/social-science.html The Hand-Loom Weaver and the Power Loom: A Schumpeterian Perspective REVISED by Robert C. Allen Global Distinguished Professor of Economic History Faculty of Social Science New York University Abu Dhabi P.O. Box 129188 Abu Dhabi United Arab Emirates Senior Research Fellow Oxford University Nuffield College New Road Oxford OX1 1NH United Kingdom [email protected] The empirics of this paper rest on John Lyon’s Ph.D. dissertation The Lancashire Cotton Industry and the Introduction of this Powerloom, 1815-1850. This is an impressively well informed and thorough reconstruction of the technology and economics of the industry. This paper could not have been written without it. John Lyons sadly died in 2011. I dedicate the paper to him. This is a revised version of a discussion paper originally issued as Oxford University, Working Papers in Economic and Social History, Number 142, 2016 2017 Abstract Robert C. Allen The Hand Loom Weaver and the Power Loom: A Schumpeterian Perspective , Schumpeter’s ‘perennial gale of creative destruction’ blew strongly through Britain during the Industrial Revolution, as the factory mode of production displaced the cottage mode in many industries. A famous example is the shift from hand loom weaving to the use of power looms in mills. As the use of power looms expanded, the price of cloth fell, and the ‘golden age of the hand loom weaver’ gave way to poverty and unemployment. -

Appendix 1: Inventions and Innovations - Britain C

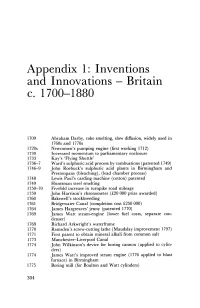

Appendix 1: Inventions and Innovations - Britain c. 1700-1880 1709 Abraham Darby, coke smelting, slow diffusion, widely used in 1760s and 1770s 1720s Newcomen's pumping engine (first working 1712) 1730 Increased momentum to parliamentary enclosure 1733 Kay's 'Flying Shuttle' 1736--7 Ward's sulphuric acid process by combustions (patented 1749) 1746--9 John Roebuck's sulphuric acid plants in Birmingham and Prestonpans (bleaching), (lead chamber process) 1748 Lewis Paul's carding machine (cotton) patented 1749 Huntsman steel smelting 1750--70 Fivefold increase in turnpike road mileage 1759 John Harrison's chronometer (£20000 prize awarded) 1760 Bakewell's stockbreeding 1761 Bridgewater Canal (completion cost £250000) 1764 James Hargreaves' jenny (patented 1770) 1769 J ames Watt steam-engine (lower fuel costs, separate con denser) 1769 Richard Arkwright's waterframe 1770 Ramsden's screw-cutting lathe (Maudslay improvement 1797) 1771 First patent to obtain mineral alkali from common salt 1773 Manchester-Liverpool Canal 1774 John Wilkinson's device for boring cannon (applied to cylin ders) 1774 J ames Watt's improved steam engine (1776 applied to blast furnace) in Birmingham 1775 Boring mill (for Boulton and Watt cylinders) 304 INVENTIONS AND INNOVATIONS 1700--1300 305 1779 Samuel Crompton's mule 1779 Cast-iron bridge of Abraham Darby at Coalbrookdale 1780 Hornblower's compound engine (high pressure cylinder to Watt engine) first working 1782 Watt's 'parallel motion' (beam and piston-rod of steam engine) 1782 Jethro Tull's geared seed-drill (slow diffusion) 1784 Cart's puddling process (puddling achieved from 1779, not taken up until c.181O), for wrought-iron manufacture 1784 First mail coaches; I 780s stage-coaches generally. -

Patterns of Innovation During the Industrial Revolution: a Reappraisal Using a Composite Indicator of Patent Quality

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Nuvolari, Alessandro; Tartari, Valentina; Tranchero, Matteo Working Paper Patterns of innovation during the Industrial Revolution: A reappraisal using a composite indicator of patent quality LEM Working Paper Series, No. 2020/23 Provided in Cooperation with: Laboratory of Economics and Management (LEM), Sant'Anna School of Advanced Studies Suggested Citation: Nuvolari, Alessandro; Tartari, Valentina; Tranchero, Matteo (2020) : Patterns of innovation during the Industrial Revolution: A reappraisal using a composite indicator of patent quality, LEM Working Paper Series, No. 2020/23, Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna, Laboratory of Economics and Management (LEM), Pisa This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/228162 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence.