Pasolini According to Patti Smith ISSN 1824-5226 D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Incurable Cancer Patient at the End of Life

Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 1013 _____________________________ _____________________________ The Incurable Cancer Patient at the End of Life Medical Care Utilization, Quality of Life and the Additive Analgesic Effect of Paracetamol in Concurrent Morphine Therapy BY BERTIL AXELSSON ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS UPPSALA 2001 Dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Faculty of Medicine) in General Surgery, presented at Uppsala University in 2001 ABSTRACT Axelsson, B. 2001. The incurable cancer patient at the end of life. Medical care utilization, quality of life and the additive analgesic effect of paracetamol in concurrent morphine therapy. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 1013. 88 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-554-4968-9. Optimal quality of life and health care utilization are objectives of all palliative services. The aim of this study was to present background data on health care utilization and quality of life, explore potential outcome variables of health care utilization, evaluate a hospital-based palliative support service, provide a quality of life tool specially designed for incurable patients at the end of life and to establish whether paracetamol has an additive analgesic effect to morphine. Only 12% of the patients died at home. When the period between diagnosis and death was less than one month, every patient died in an institution. Younger patients, married patients, and those living within a 40 km radius of the hospital utilized more hospital days. The "length of terminal hospitalization" and the "proportion of days at home/total inclusion days" seemed to be feasible outcome variables when evaluating a palliative support service. -

Babel by Patti Smith

Read and Download Ebook Babel... Babel Patti Smith PDF File: Babel... 1 Read and Download Ebook Babel... Babel Patti Smith Babel Patti Smith Babel Details Date : ISBN : 9780425042304 Author : Patti Smith Format : Genre : Poetry, Music, Fiction, Punk Download Babel ...pdf Read Online Babel ...pdf Download and Read Free Online Babel Patti Smith PDF File: Babel... 2 Read and Download Ebook Babel... From Reader Review Babel for online ebook Bradley says Published only as a first edition in 1978, "Babel" is a collection of poetry, prose, and stream of consciousness writing. With inspiration drawn from Rimbaud and the Beats, Smith paints a unique portrait of late 70s New York City. Rock music, sex, and Smith's life are graphically and beautifully illustrated. Smith's first album "Horses" was just three years earlier. Some of the writing in this book later appeared as spoken word monologues on her albums including "Babelogue" which appears on her 1978 release "Easter." Smith is undeniably the Godmother of Punk. While this book truly encapsulates the essence of her life and struggles in New York during the 70s, it isn't a very polished collection. With lowercase text, misspelled words, and improper punctuation, the writing can be challenging at times. However, perhaps that's the point. What could be more punk in the literary world than defying all literature's conventions? Jamie Ruiz says Wicked! Jennifer says Patti Smith is a true American artist and though her poetry tends to be more like an American Rimbaud, crude, poignant, and funny, she is not for everyone. The godmother of punk she is now in her 60's and still remains articulate and true to her artform. -

PATTI SMITH Eighteen Stations MARCH 3 – APRIL 16, 2016

/robertmillergallery For immediate release: [email protected] @RMillerGallery 212.366.4774 /robertmillergallery PATTI SMITH Eighteen Stations MARCH 3 – APRIL 16, 2016 New York, NY – February 17, 2016. Robert Miller Gallery is pleased to announce Eighteen Stations, a special project by Patti Smith. Eighteen Stations revolves around the world of M Train, Smith’s bestselling book released in 2015. M Train chronicles, as Smith describes, “a roadmap to my life,” as told from the seats of the cafés and dwellings she has worked from globally. Reflecting the themes and sensibility of the book, Eighteen Stations is a meditation on the act of artistic creation. It features the artist’s illustrative photographs that accompany the book’s pages, along with works by Smith that speak to art and literature’s potential to offer hope and consolation. The artist will be reading from M Train at the Gallery throughout the run of the exhibition. Patti Smith (b. 1946) has been represented by Robert Miller Gallery since her joint debut with Robert Mapplethorpe, Film and Stills, opened at its 724 Fifth Avenue location in 1978. Recent solo exhibitions at the Gallery include Veil (2009) and A Pythagorean Traveler (2006). In 2014 Rockaway Artist Alliance and MoMA PS1 mounted Patti Smith: Resilience of the Dreamer at Fort Tilden, as part of a special project recognizing the ongoing recovery of the Rockaway Peninsula, where the artist has a home. Smith's work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at institutions worldwide including the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto (2013); Detroit Institute of Arts (2012); Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford (2011); Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporaine, Paris (2008); Haus der Kunst, Munich (2003); and The Andy Warhol Museum (2002). -

A Selective Study of the Writings of Kafka, Kubin, Meyrink, Musil and Schnitzler

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses The literary dream in German Central Europe, 1900-1925: A selective study of the writings of Kafka, Kubin, Meyrink, Musil and Schnitzler. Vrba, Marya How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Vrba, Marya (2011) The literary dream in German Central Europe, 1900-1925: A selective study of the writings of Kafka, Kubin, Meyrink, Musil and Schnitzler.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42396 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ The Literary Dream in German Central Europe, 1900-1925 A Selective Study of the Writings of Kafka, Kubin, Meyrink, Musil and Schnitzler Mary a Vrba Thesis submitted to Swansea University in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Modern Languages Swansea University 2011 ProQuest Number: 10798104 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

John Ciardi Collection, Metuchen-Edison Historical Society, Metuchen, N.J

Finding Guide & Inventory John Ciardi Collection Metuchen-EdisonPage Historical 1 Society Our Mission The mission of the Metuchen-Edison Historical Society (MEHS) is to stimulate and promote an interest in and an appreciation of the history of the geographic area in and around the Borough of Metuchen and the Township of Edison in the County of Middlesex, New Jersey. To fulfill this mission, the society fosters the creation, collection, preservation, and maintenance of physical material related to the history of Metuchen and Edison, makes the material available to the public in various formats, and increases public awareness of this history. Board of Directors Steve Reuter, President Dominic Walker, Vice President Walter R. Stochel, Jr, Treasurer Marilyn Langholff, Recording Secretary Tyreen Reuter, Corresponding Secretary & Newsletter Editor Phyllis Boeddinghaus Russell Gehrum Kathy Glaser Lauren Kane Andy Kupersmit Catherine Langholff Byron Sondergard Frederick Wolke Marie Vajo Researchers wishing to cite this collection should include the following information: John Ciardi Collection, Metuchen-Edison Historical Society, Metuchen, N.J. ISBN-10: 1940714001 ISBN-13: 978-1-940714-00-4 September,Space 2013 reserved for optional ISBN and bar code. All Rights Reserved. Cover Image: W.C. Dripps Map of Metuchen, Middlesex County, New Jersey, 1876. Page 2 John Ciardi Collection Finding Guide & Inventory Grant Funding has been provided by the Middlesex County Cultural & Heritage Commission Middlesex County Board of Chosen Freeholders through a -

Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry Emily Rutter

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014 Constructions of the Muse: Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry Emily Rutter Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Rutter, E. (2014). Constructions of the Muse: Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1136 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Emily Ruth Rutter March 2014 Copyright by Emily Ruth Rutter 2014 ii CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY By Emily Ruth Rutter Approved March 12, 2014 ________________________________ ________________________________ Linda A. Kinnahan Kathy L. Glass Professor of English Associate Professor of English (Committee Chair) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ Laura Engel Thomas P. Kinnahan Associate Professor of English Assistant Professor of English (Committee Member) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ James Swindal Greg Barnhisel Dean, McAnulty College of Liberal Arts Chair, English Department Professor of Philosophy Associate Professor of English iii ABSTRACT CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY By Emily Ruth Rutter March 2014 Dissertation supervised by Professor Linda A. -

Catalogue 143 ~ Holiday 2008 Contents

Between the Covers - Rare Books, Inc. 112 Nicholson Rd (856) 456-8008 will be billed to meet their requirements. We accept Visa, MasterCard, American Express, Discover, and Gloucester City NJ 08030 Fax (856) 456-7675 PayPal. www.betweenthecovers.com [email protected] Domestic orders please include $5.00 postage for the first item, $2.00 for each item thereafter. Images are not to scale. All books are returnable within ten days if returned in Overseas orders will be sent airmail at cost (unless other arrange- the same condition as sent. Books may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. ments are requested). All items insured. NJ residents please add 7% sales tax. All items subject to prior sale. Payment should accompany order if you are Members ABAA, ILAB. unknown to us. Customers known to us will be invoiced with payment due in 30 days. Payment schedule may be adjusted for larger purchases. Institutions Cover verse and design by Tom Bloom © 2008 Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. Catalogue 143 ~ Holiday 2008 Contents: ................................................................Page Literature (General Fiction & Non-Fiction) ...........................1 Baseball ................................................................................72 African-Americana ...............................................................55 Photography & Illustration ..................................................75 Children’s Books ..................................................................59 Music ...................................................................................80 -

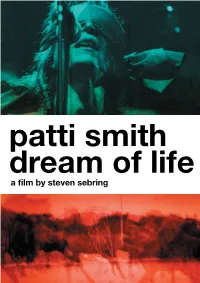

Patti DP.Indd

patti smith dream of life a film by steven sebring THIRTEEN/WNET NEW YORK AND CLEAN SOCKS PRESENT PATTI SMITH AND THE BAND: LENNY KAYE OLIVER RAY TONY SHANAHAN JAY DEE DAUGHERTY AND JACKSON SMITH JESSE SMITH DIRECTORS OF TOM VERLAINE SAM SHEPARD PHILIP GLASS BENJAMIN SMOKE FLEA DIRECTOR STEVEN SEBRING PRODUCERS STEVEN SEBRING MARGARET SMILOW SCOTT VOGEL PHOTOGRAPHY PHILLIP HUNT EXECUTIVE CREATIVE STEVEN SEBRING EDITORS ANGELO CORRAO, A.C.E, LIN POLITO PRODUCERS STEVEN SEBRING MARGARET SMILOW CONSULTANT SHOSHANA SEBRING LINE PRODUCER SONOKO AOYAGI LEOPOLD SUPERVISING INTERNATIONAL PRODUCERS JUNKO TSUNASHIMA KRISTIN LOVEJOY DISTRIBUTION BY CELLULOID DREAMS Thirteen / WNET New York and Clean Socks present Independent Film Competition: Documentary patti smith dream of life a film by steven sebring USA - 2008 - Color/B&W - 109 min - 1:66 - Dolby SRD - English www.dreamoflifethemovie.com WORLD SALES INTERNATIONAL PRESS CELLULOID DREAMS INTERNATIONAL HOUSE OF PUBLICITY 2 rue Turgot Sundance office located at the Festival Headquarters 75009 Paris, France Marriott Sidewinder Dr. T : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0370 F : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0371 Jeff Hill – cell: 917-575-8808 [email protected] E: [email protected] www.celluloid-dreams.com Michelle Moretta – cell: 917-749-5578 E: [email protected] synopsis Dream of Life is a plunge into the philosophy and artistry of cult rocker Patti Smith. This portrait of the legendary singer, artist and poet explores themes of spirituality, history and self expression. Known as the godmother of punk, she emerged in the 1970’s, galvanizing the music scene with her unique style of poetic rage, music and trademark swagger. -

MURDER III VICTOR. SID DEATH of CHILDN ELECTRICAL Stormsb

- The Clinton 54th Year—No. 20. ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN, THURSDAY, AUGUST 5, 1909. Whole No. 2773. VARIOUS TOPICS. WILL WATERS ANOTHER PIONEER MURDER III VICTOR. A committee of I-anaing ladles have SID DEATH OF CHILDNArrested at Owosso on Charge of Sim ELECTRICAL STORMSbMrs Hugh Merrihew of Olive Died IH^POMOIIA RALLY Issued an appeal, asking a thousand ple Larceny. M -------- Thursday. friends to contribute one dollar each Held at Fair Grounds at St. John Haker, Aged 81, Killed toward the Lansing hospital. Bean Lodges in Throat of Destroyed Barns and Killed A week ago last Friday, a young man # Mrs. Hugh Merrihew. a resident of Johns Yesterday. Friday by Wife, Aged 44. The marriage of Louis J. Voislnet NJ Leola Martin. by the name of Will Waters was em Live Stock. Olive township since 1856, died last of HaWlffDeWitt andon/I \flcoMiss IdaTHo M.\f FavlerParlor of - ployed by Elmer Stoweli of Ovid on Thursday. Olive is announced for August 17th, some concrete work ln Riley township. Mrs. Merrihew was born May 12. ABOUT 250 PRESENT. SHOT HIM IN BACK and will be solemnized at St. Joseph's TAKEN TO ANN ARBOR. On July "23d, at noon Mr. Stoweli dis IN COUNTY AND STATE 1830, ln Ulster county, New York, Catholic church in this city. charged the boy. residing there until a few pears after -------- NT Breathed Only By Tub* in Windpip< That night when Mr. Stoweli went to her marriage to Mr. Merrihew, March Hon. D. E. McClure of Muskegon Gave Couple Were Divorced a Few Week* js, his tent which was pitched near his Big Cloudburst at Ionia Yesterday— 27th, 1850. -

Babel' in Context a Study in Cultural Identity B O R D E R L I N E S : R U S S I a N А N D E a S T E U R O P E a N J E W I S H S T U D I E S

Babel' in Context A Study in Cultural Identity B o r d e r l i n e s : r u s s i a n а n d e a s t e u r o p e a n J e w i s h s t u d i e s Series Editor: Harriet Murav—University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Editorial board: Mikhail KrutiKov—University of Michigan alice NakhiMovsKy—Colgate University David Shneer—University of Colorado, Boulder anna ShterNsHis—University of Toronto Babel' in Context A Study in Cultural Identity Ef r a i m Sic hEr BOSTON / 2012 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A catalog record for this book as available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2012 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved Effective July 29, 2016, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. ISBN 978-1-936235-95-7 Cloth ISBN 978-1-61811-145-6 Electronic Book design by Ivan Grave Published by Academic Studies Press in 2012 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com C o n t e n t s Note on References and Translations 8 Acknowledgments 9 Introduction 11 1 / Isaak Babelʹ: A Brief Life 29 2 / Reference and Interference 85 3 / Babelʹ, Bialik, and Others 108 4 / Midrash and History: A Key to the Babelesque Imagination 129 5 / A Russian Maupassant 151 6 / Babelʹ’s Civil War 170 7 / A Voyeur on a Collective Farm 208 Bibliography of Works by Babelʹ and Recommended Reading 228 Notes 252 Index 289 Illustrations Babelʹ with his father, Nikolaev 1904 32 Babelʹ with his schoolmates 33 Benia Krik (still from the film, Benia Krik, 1926) 37 S. -

The Optic and the Semiotic in the Novels of Amit Chaudhuri

THE OPTIC AND THE SEMIOTIC IN THE NOVELS OF AMIT CHAUDHURI SUMANA ROY THESIS SUBMITTED FOR Ph.D DEGREE UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROFESSOR G. N. RAY AT THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL, 2007 g23-033 •3< ggg'O 20582O 2 6 MAY li^Oti Contents Acknowledgements 1 Preface 2 Introduction 6 Chapter 1 The Text as Rhizome: Amit Chaudhuri's Theory of Fiction 16 Chapter 2 Whose Space is it anyway? The Politics of Translation on the Printed Page 26 Chapter 3 The Metonymised Body: Exploring the Semiotic of the Body 44 Chapter 4 Salt, Sugar, Spice: The Food Dis(h)-course 62 Chapter 5 This is Not Fusion: Then what is? 84 Chapter 6 'Eh Stupid!' 'Saala!': The 'Impolite' in Chaudhuri's Fiction 97 Chapter 7 Under Cover: The Cover Illustrations of the Books of Amit Chaudhuri 121 Chapter 8 "I send you this poem": The optic and the codes of exchange in Chaudhuri's Poems 128 Bibliography 148 Appendix Aalap: In Conversation with Amit Chaudhuri 154 Novelist on Narratives 178 Published Chapters 184 Acknowledgements Every PhD student begins by acknowledging her gratitude and debt to her supervisor and I will continue with the tradition; only, in my case, my gratitude would extend to subjects beyond the scope of this dissertation. Among all the generous gifts that I have received from Professor G. N. Ray, I must mention one that I value over others - his patience with a moody doctoral student like me. I would also like to acknowledge my gratitude to two of my professors. -

Queens Park Music Club

Alan Currall BBobob CareyCarey Grieve Grieve Brian Beadie Brian Beadie Clemens Wilhelm CDavidleme Hoylens Wilhelm DDavidavid MichaelHoyle Clarke DGavinavid MaitlandMichael Clarke GDouglasavin M aMorlanditland DEilidhoug lShortas Morland Queens Park Music Club EGayleilidh MiekleShort GHrafnhildurHalldayle Miekle órsdóttir Volume 1 : Kling Klang Jack Wrigley ó ó April 2014 HrafnhildurHalld rsd ttir JJanieack WNicollrigley Jon Burgerman Janie Nicoll Martin Herbert JMauriceon Burg Dohertyerman MMelissaartin H Canbazerbert MMichelleaurice Hannah Doherty MNeileli Clementsssa Canbaz MPennyichel Arcadele Hannah NRobeil ChurmClements PRoben nKennedyy Arcade RobRose Chu Ruanerm RoseStewart Ruane Home RobTom MasonKennedy Vernon and Burns Tom Mason Victoria Morton Stuart Home Vernon and Burns Victoria Morton Martin Herbert The Mic and Me I started publishing criticism in 1996, but I only When you are, as Walter Becker once learned how to write in a way that felt and still sang, on the balls of your ass, you need something feels like my writing in about 2002. There were to lift you and hip hop, for me, was it, even very a lot of contributing factors to this—having been mainstream rap: the vaulting self-confidence, unexpectedly bounced out of a dotcom job that had seesawing beat and herculean handclaps of previously meant I didn’t have to rely on freelancing Eminem’s armour-plated Til I Collapse, for example. for income, leaving London for a slower pace of A song like that says I am going to destroy life on the coast, and reading nonfiction writers everybody else. That’s the braggadocio that hip who taught me about voice and how to arrange hop has always thrived on, but it is laughable for a facts—but one of the main triggers, weirdly enough, critic to want to feel like that: that’s not, officially, was hip hop.