Coronavirus Covid-19 in Papua New Guinea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil Aviation Development Investment Program (Tranche 3)

Resettlement Due Diligence Reports Project Number: 43141-044 June 2016 PNG: Multitranche Financing Facility - Civil Aviation Development Investment Program (Tranche 3) Prepared by National Airports Corporation for the Asian Development Bank. This resettlement due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Table of Contents B. Resettlement Due Diligence Report 1. Madang Airport Due Diligence Report 2. Mendi Airport Due Diligence Report 3. Momote Airport Due Diligence Report 4. Mt. Hagen Due Diligence Report 5. Vanimo Airport Due Diligence Report 6. Wewak Airport Due Diligence Report 4. Madang Airport Due Diligence Report. I. OUTLINE FOR MADANG AIRPORT DUE DILIGENCE REPORT 1. The is a Due Diligent Report (DDR) that reviews the Pavement Strengthening Upgrading, & Associated Works proposed for the Madang Airport in Madang Province (MP). It presents social safeguard aspects/social impacts assessment of the proposed works and mitigation measures. II. BACKGROUND INFORMATION 2. Madang Airport is situated at 5° 12 30 S, 145° 47 0 E in Madang and is about 5km from Madang Town, Provincial Headquarters of Madang Province where banks, post office, business houses, hotels and guest houses are located. -

Health&Medicalinfoupdate8/10/2017 Page 1 HEALTH and MEDICAL

HEALTH AND MEDICAL INFORMATION The American Embassy assumes no responsibility for the professional ability or integrity of the persons, centers, or hospitals appearing on this list. The names of doctors are listed in alphabetical, specialty and regional order. The order in which this information appears has no other significance. Routine care is generally available from general practitioners or family practice professionals. Care from specialists is by referral only, which means you first visit the general practitioner before seeing the specialist. Most specialists have private offices (called “surgeries” or “clinic”), as well as consulting and treatment rooms located in Medical Centers attached to the main teaching hospitals. Residential areas are served by a large number of general practitioners who can take care of most general illnesses The U.S Government assumes no responsibility for payment of medical expenses for private individuals. The Social Security Medicare Program does not provide coverage for hospital or medical outside the U.S.A. For further information please see our information sheet entitled “Medical Information for American Traveling Abroad.” IMPORTANT EMERGENCY NUMBERS AMBULANCE/EMERGENCY SERVICES (National Capital District only) Police: 112 / (675) 324-4200 Fire: 110 St John Ambulance: 111 Life-line: 326-0011 / 326-1680 Mental Health Services: 301-3694 HIV/AIDS info: 323-6161 MEDEVAC Niugini Air Rescue Tel (675) 323-2033 Fax (675) 323-5244 Airport (675) 323-4700; A/H Mobile (675) 683-0305 Toll free: 0561293722468 - 24hrs Medevac Pacific Services: Tel (675) 323-5626; 325-6633 Mobile (675) 683-8767 PNG Wide Toll free: 1801 911 / 76835227 – 24hrs Health&MedicalInfoupdate8/10/2017 Page 1 AMR Air Ambulance 8001 South InterPort Blvd Ste. -

Papua New Guinea (And Comparators)

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized BELOW THE GLASS FLOOR Analytical Review of Expenditure by Provincial Administrations on Rural Health from Health Function Grants & Provincial Internal Revenue JULY 2013 Below the Glass Floor: An Analytical Review of Provincial Administrations’ Rural Health Expenditure Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750- 8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street, NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax 202-522-2422; email: [email protected]. - i - Below the Glass Floor: An Analytical Review of Provincial Administrations’ Rural Health Expenditure Table of Contents Acknowledgment ......................................................................................................................... 5 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................. -

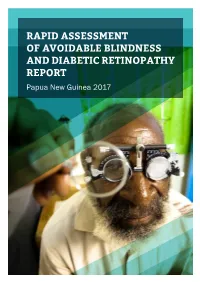

RAPID ASSESSMENT of AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS and DIABETIC RETINOPATHY REPORT Papua New Guinea 2017

RAPID ASSESSMENT OF AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS AND DIABETIC RETINOPATHY REPORT Papua New Guinea 2017 RAPID ASSESSMENT OF AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS AND DIABETIC RETINOPATHY PAPUA NEW GUINEA, 2017 1 Acknowledgements The Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness (RAAB) + Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) was a Brien Holden Vision Institute (the Institute) project, conducted in cooperation with the Institute’s partner in Papua New Guinea (PNG) – PNG Eye Care. We would like to sincerely thank the Fred Hollows Foundation, Australia for providing project funding, PNG Eye Care for managing the field work logistics, Fred Hollows New Zealand for providing expertise to the steering committee, Dr Hans Limburg and Dr Ana Cama for providing the RAAB training. We also wish to acknowledge the National Prevention of Blindness Committee in PNG and the following individuals for their tremendous contributions: Dr Jambi Garap – President of National Prevention of Blindness Committee PNG, Board President of PNG Eye Care Dr Simon Melengas – Chief Ophthalmologist PNG Dr Geoffrey Wabulembo - Paediatric ophthalmologist, University of PNG and CBM Mr Samuel Koim – General Manager, PNG Eye Care Dr Georgia Guldan – Professor of Public Health, Acting Head of Division of Public Health, School of Medical and Health Services, University of PNG Dr Apisai Kerek – Ophthalmologist, Port Moresby General Hospital Dr Robert Ko – Ophthalmologist, Port Moresby General Hospital Dr David Pahau – Ophthalmologist, Boram General Hospital Dr Waimbe Wahamu – Ophthalmologist, Mt Hagen Hospital Ms Theresa Gende -

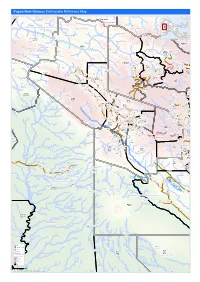

Earthquake Reference Map

Papua New Guinea: Earthquake Reference Map Telefomin London Rural Lybia Telefomin Tunap/Hustein District Ambunti/Drekikier District Kaskare Akiapjmin WEST SEPIK (SANDAUN) PROVINCE Karawari Angoram EAST SEPIK PROVINCE Rural District Monduban HELA PROVINCE Wundu Yatoam Airstrip Lembana Kulupu Malaumanda Kasakali Paflin Koroba/Kopiago Kotkot Sisamin Pai District Emo Airstrip Biak Pokale Oksapmin Liawep Wabag Malandu Rural Wayalima District Hewa Airstrip Maramuni Kuiva Pauteke Mitiganap Teranap Lake Tokom Rural Betianap Puali Kopiago Semeti Oksapmin Sub Aipaka Yoliape Waulup Oksapmin District ekap Airport Rural Kenalipa Seremty Divanap Ranimap Kusanap Tomianap Papake Lagaip/Pogera Tekin Winjaka Airport Gawa Eyaka Airstrip Wane 2 District Waili/Waki Kweptanap Gaua Maip Wobagen Wane 1 Airstrip aburap Muritaka Yalum Bak Rural imin Airstrip Duban Yumonda Yokona Tili Kuli Balia Kariapuka Yakatone Yeim Umanap Wiski Aid Post Poreak Sungtem Walya Agali Ipate Airstrip Piawe Wangialo Bealo Paiela/Hewa Tombaip Kulipanda Waimalama Pimaka Ipalopa Tokos Ipalopa Lambusilama Rural Primary Tombena Waiyonga Waimalama Taipoko School Tumundane Komanga ANDS HIG PHaLin Yambali Kolombi Porgera Yambuli Kakuane C/Mission Paiela Aspiringa Maip Pokolip Torenam ALUNI Muritaka Airport Tagoba Primary Kopetes Yagoane Aiyukuni SDA Mission Kopiago Paitenges Haku KOPIAGO STATION Rural Lesai Pali Airport School Yakimak Apostolic Mission Politika Tamakale Koemale Kambe Piri Tarane Pirika Takuup Dilini Ingilep Kiya Tipinini Koemale Ayene Sindawna Taronga Kasap Luth. Yaparep -

Estimating Adult Mortality in Papua New Guinea, 2011 Urarang Kitur* , Tim Adair and Alan D

Kitur et al. Population Health Metrics (2019) 17:4 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12963-019-0184-x RESEARCH Open Access Estimating Adult Mortality in Papua New Guinea, 2011 Urarang Kitur* , Tim Adair and Alan D. Lopez Abstract Background: Mortality in Papua New Guinea (PNG) is poorly measured because routine reporting of deaths is incomplete and inaccurate. This study provides the first estimates in the academic literature of adult mortality (45q15) in PNG by province and sex. These results are compared to a Composite Index of provincial socio- economic factors and health access. Methods: Adult mortality estimates (45q15) by province and sex were derived using the orphanhood method from data reported in the 2000 and 2011 national censuses. Male adult mortality was adjusted based on the estimated incompleteness of mortality reporting. The Composite Index was developed using the mean of education, economic and health access indicators from various data sources. Results: Adult mortality for PNG in 2011 was estimated as 269 per 1000 for males and 237 for females. It ranged from 197 in Simbu to 356 in Sandaun province among men, and from 164 in Western Highlands to 326 in Gulf province among women. Provinces with a low Composite Index (Sandaun, Gulf, Enga and Southern Highlands) had comparatively high levels of adult mortality for both sexes, while provinces with a higher Composite Index (National Capital District and Manus) reported lower adult mortality. Conclusions: Adult mortality in PNG remains high compared with other developing countries. Provincial variations in mortality correlate with the Composite Index. Health and development policy in PNG needs to urgently address the main causes of persistent high premature adult mortality, particularly in less developed provinces. -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 250 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feed- back goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. Chris, Serah, Donaldson, Bob, Lisa and Pam, OUR READERS who went out of their way to help me. And Many thanks to the travellers who used the finally, once again a gros bisou to Christine, last edition and wrote to us with helpful who supported me. hints, useful advice and interesting anec- dotes. Berna Collier, Bernard Hayes, Blake Anna Kaminski Everson, Caspar Dama, Charlie Lynn, Diarne Kreltszheim, Fred Lazell, Haya Zommer, Joanna I would like to thank Tasmin for entrusting me O’Shea, Lynne Cannell, Manuel Hetzel, Markus with research of the most fascinating country Eifried, Martijn Maandag, Rebecca Nava, Tim I’ve ever covered; my fellow scribes, Lindsay Bridgeman, Zoltan & Anna Szabo and JB; and everyone who’s helped me along the way. -

MOMASE REGION • East Sepik Province • Madang Province

MOMASE REGION • East Sepik Province • Madang Province • Morobe Province • Sandaun Province (West Sepik) Meri Toksave 2014/ 2015 38 EAST SEPIK PROVINCE Hospitals • Boram Wewak General Hospital Located at Boram site Rd. Operating hours: 8am-6pm. Ph: 456 2166 • Maprik District Hospital Ph: 71487280 or the Family Support Centre: 70859361 or 71395068 Police • Wewak Police Station Located in the heart of Wewak town. Ph: 456 2633 Counselling • Nana Kundi Crisis Centre Based in Maprik district. Nana Kundi Crisis Centre provides: Counselling, mediations (conflict resolutions), men and boys outreach awareness, Paralegal support, welfare services (as part of counselling) referrals and repatriation. Opening hours: 8am - 4pm Ph: landline is not working but the centre still operates. • St Anna’s Crisis Centre Based in Wasara. Provides the following services: counselling, crisis service support, mediation, men and boys outreach and referrals. Ph: 71325060 Meri Toksave 2014/ 2015 39 • Mama Emma Based in Gawi. Provides the following services: Crisis service support, men and boys outreach, counselling, mediation and referrals, legal advice. Ph: 70236018 • Family for Change Based in Wewak town. Provides the following services: crisis service support, mediation, counselling, paralegal support, family support, men and boys outreach awareness and referrals. Opening hours: Not operating on Saturdays. Ph: 73778013 • Youth Friendly Centre Location: In Maprik just on the main highway leading to west Sepik, adjacent to local level government officer. Right in town. Services: counseling for issues affecting young people (trauma, violence, abuse, family issues). Ph: 73976140 Legal Advice • Nana Kundi Crisis Centre Based in Maprik district. Nana Kundi Crisis Centre provides: Counselling, mediations (conflict resolutions), men and boys outreach awareness, Paralegal support, welfare services (as part of counselling) referrals and repatriation. -

TCA Capability Statement

CAPABILITY STATEMENT Organisation Profile The Tenkile Conservation Alliance (TCA) focuses on the Scott’s Tree Kangaroo (Tenkile) and Golden- mantled Tree Kangaroo (Weimang) as flagship species for achieving broad forest biodiversity conservation outcomes in the Torricelli Mountain Range, Sandaun and East Sepik Provinces, Papua New Guinea (PNG). Our main objective is to establish this mountain range as a legislated Conservation Area. In order to achieve this goal the TCA has been working closely with the 50 villages that own the Torricelli Mountain Range. An award winning organisation, TCA has become internationally recognised by top scientists including Professor Tim Flannery, Dr Jane Goodall and Sir David Attenborough. TCA prides itself in taking a holistic approach to achieving conservation objectives and strengthening the relationship with the local stakeholders. Flexibility, determination and passion are key drivers behind our success. Organisation Experience TCA has been established in Lumi, Sandaun Province since 2001 and is a registered Non-government Organisation in PNG. Our extensive experience of working in collaborative partnerships with local stakeholders, international partners and donor organisations delivering a range of projects means we can provide a comprehensive portfolio of consultancy and advisory services in the following area of work: • Community engagement and mobilisation • Community Education and communication • Community planning, organisation and management training • Community development, project design and implementation • Project implementation and logistics in a rural environment • Capacity Building for local grassroots people in PNG • Scientific research and biodiversity assessment Key Projects Community engagement and mobilisation A variety of community engagement activities have been undertaken since 2004. These activities have been designed and implemented throughout the TCA project area, which comprises 50 villages and a population greater than 12,000 people. -

(Elapidae- Hydrophiinae), With

1 The taxonomic history of the enigmatic Papuan snake genus Toxicocalamus 2 (Elapidae: Hydrophiinae), with the description of a new species from the 3 Managalas Plateau of Oro Province, Papua New Guinea, and a revised 4 dichotomous key 5 6 Mark O’Shea1, Allen Allison2, Hinrich Kaiser3 7 8 1 Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Wolverhampton, Wulfruna Street, 9 Wolverhampton, WV1 1LY, United Kingdom; West Midland Safari Park, Bewdley, 10 Worcestershire DY12 1LF, United Kingdom. 11 2 Department of Natural Sciences, Bishop Museum, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, 12 Hawaii 96817, U.S.A. 13 3 Department of Biology, Victor Valley College, 18422 Bear Valley Road, 14 Victorville, California 92395, U.S.A.; and Department of Vertebrate Zoology, 15 National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 16 20013, U.S.A. 17 [email protected] (corresponding author) 18 Article and Review 17,262 words 19 1 20 Abstract: We trace the taxonomic history of Toxicocalamus, a poorly known genus of 21 primarily vermivorous snakes found only in New Guinea and associated island 22 archipelagos. With only a relatively limited number of specimens to examine, and the 23 distribution of those specimens across many natural history collections, it has been a 24 difficult task to assemble a complete taxonomic assessment of this group. As a 25 consequence, research on these snakes has undergone a series of fits and starts, and we 26 here present the first comprehensive chronology of the genus, beginning with its 27 original description by George Albert Boulenger in 1896. We also describe a new 28 species from the northern versant of the Owen Stanley Range, Oro Province, Papua 29 New Guinea, and we present a series of comparisons that include heretofore underused 30 characteristics, including those of unusual scale patterns, skull details, and tail tip 31 morphology. -

Hydrographic Surveys

Scope and Technical Report: Hydrographic Surveys November 2012 PNG: Maritime and Waterways Safety Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 5 November 2012) Currency unit – kina (K) K1.00 = $0.49 $1.00 = K2.06 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AIS – Automatic Identification System AHO – Australian Hydrographic Office AHS – Australian Hydrographic Service ECDIS – Electronic Chart Display ENC – Electronic Navigation Chart FIG – International Federation of Surveyors GNSS – Global Navigation Satellite System GPS – Global Positioning System IHO – International Hydrographic Organization IMO – International Maritime Organization NIH – National Institute of Hydrography NMSA – National Maritime Safety Authority OEM – Original Equipment Manufacturer PNG – Papua New Guinea SOLAS – Safety Of Life At Sea WGS 84 – World Geodetic Spheroid 84 ZOC – Zone of Confidence WEIGHTS AND MEASURES km (kilometer) – Linear measurement m (meter) – Linear measurement nm (nautical mile) – Measurement of distance at sea knot (nautical miles/hour) – Measurement of speed at sea and in air NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars unless otherwise stated. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page A. Objectives and Scope of Work 1 B. Hydrographic Survey and Charting 1 C. Human Resources/ Manpower 4 D. Training 6 E. Equipment 6 F. Development Plan 7 G. Survey Arrangements 8 H. Recommendations 9 References 10 Appendix 1: Navigational Charts covering PNG 11 Appendix 2: Details of Areas Shown as Unsurveyed 14 Appendix 3: Listed Ports in Papua New Guinea 17 Appendix 4: Areas and Ports Identified for Large Scale Surveys 18 Appendix 5: List of Surveying Equipment held by Hydrographic Unit 23 Appendix 6: Proposed Structure and Responsibilities of Hydrographic Unit 24 Appendix 7: ESTIMATION of Time and Cost for Hydrographic Surveys 27 A. -

Agricultural Systems of Papua New Guinea

AGRICULTURAL SYSTEMS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA Working Paper No. 3 WEST SEPIK PROVINCE TEXT SUMMARIES, MAPS, CODE LISTS AND VILLAGE IDENTIFICATION R.M. Bourke, B.J. Allen, R.L. Hide, D. Fritsch, R. Grau, E. Lowes, T. Nen, E. Nirsie, J. Risimeri and M. Woruba Department of Human Geography, The Australian National University, ACT 0200, Australia. REVISED and REPRINTED 2002 Correct Citation: Bourke, R.M., Allen, B.J., Hide, R.L., Fritsch, D., Grau, R., Lowes, E., Nen, T., Nirsie, E., Risimeri, J. and Woruba, M. (2002). West Sepik Province: Text Summaries, Maps, Code Lists and Village Identification. Agricultural Systems of Papua New Guinea Working Paper No. 3. Land Management Group, Department of Human Geography, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University, Canberra. Revised edition. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry: West Sepik Province: text summaries, maps, code lists and village identification. Rev. ed. ISBN 0 9579381 3 6 1. Agricultural systems – Papua New Guinea – West Sepik Province. 2. Agricultural geography – Papua New Guinea – West Sepik Province. 3. Agricultural mapping – Papua New Guinea – West Sepik Province. I. Bourke, R.M. (Richard Michael). II. Australian National University. Land Management Group. (Series: Agricultural systems of Papua New Guinea working paper; no. 3). 630.99577 Cover Photograph: The late Gore Gabriel clearing undergrowth from a pandanus nut grove in the Sinasina area, Simbu Province (R.L. Hide). ii PREFACE Acknowledgments The following organizations have contributed financial support to this project: The Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University; The Australian Agency for International Development; the Papua New Guinea-Australia Colloquium through the International Development Program of Australian Universities and Colleges and the Papua New Guinea National Research Institute; the Papua New Guinea Department of Agriculture and Livestock; the University of Papua New Guinea; and the National Geographic Society, Washington DC.