Jamia Journal of Education (An International Biannual Publication)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetic Structure of Tribes of Bihar-Proposed Easy

ANTHROPOLOGICAL GENETICS Int. J. Mendel, Vol. 35(1-2), 2018 & 36(1-2), 2019 183-186 ISSN0970-9649 GENETIC STRUCTURE OF TRIBES OF BIHAR-PROPOSED EASY METHODOLOGIES AND SOME NOTABLE CONTRIBUTIONS Indrani Trivedi* and M.P.Trivedi** Key words : Genetic structure, Tribes,Bihar, Proposed methodologies, Notable contributions The gene frequency data are pre-requisite for knowing genetic structure of human population. The variations in gene pool are due to selection, migration, mutation,and genetic drift. There is meagre work available on genetic structure of tribes of Bihar. Some achievements have been highlighted and need more work to reach conclusions. INTRODUCTION We, Homo sapiens are product of biology and culture. We always strive for a better life. Humans migrate from one place to another in response to better habitat and food opportunity. Every individual has its own genetic constitution. Their unique genetic structure help them in fighting diseases and finally adaptation. The genetic structure of human populations is significant to study ethnic relationship. Encoded history of migration and remote past are carried in the genes of modern human population. Human populations differ genetically in varying proportions of the alleles of various sets. Biological variations in humans are related to the ethnic and ecological background of population. The genetic similarities indicate common origin. The variations in gene pool may be due to mutation, selection, migration and genetic drift. The gene pool is not a simple sum of genes, but is a dynamic system which is hierarchically organized and which maintains the memory of past events in the history of populations.The gene frequency data are pre-requisite for knowing genetic structure of human populations. -

Private Voting and Public Outcomes in Elections in Rural India [PDF, 166KB

ASARC Working Paper 2011/09 ALIGNING WITH ONE’S OWN: Private Voting and Public Outcomes in Elections in Rural India# Raghbendra Jha Hari K. Nagarajan Kailash C. Pradhan Australian National University, NCAER, New Delhi NCAER, New Delhi Canberra Abstract This paper has the objective of showing that identity based voting will lead to improvements in household welfare through increased access to welfare programs. Using newly available data from rural India, we establish that identity based voting will lead to enhanced participation in welfare programs and increased consumption growth. We also show that consumption growth is retarded if households do not engage in identity based voting. Using 3 stage least squares, we are able to show that identity based voting results from the externalities derived from membership in social and information networks, and such voting by enhancing participation in welfare programs leads to significant increases in household consumption growth. Key Words: Identity Based Voting, Panchayats, Decentralization, Devolution JEl Classification: D7, D72, D73 # This paper is part of the IDRC–NCAER research program on “Building Policy Research Capacity for Rural Governance and Growth in India” (grant number 105223). We wish to thank Hans Binswanger and Andrew Foster for comments on earlier drafts. The usual caveat applies. Raghbendra Jha, Hari K Nagarajan & Kailash C Pradhan Right wing academic force — particularly a group of sociologists and anthropologists — advised the Bharatiya Janata Party led National Democratic Alliance Government not to go for caste based census in 2001 as it would go against the ruling upper castes and communities. It is fallacious to argue that society will get further divided if the population of each caste is known to the policy maker and public…It is true that we cannot distribute everything based on caste. -

Private Voting and Public Outcomes in Rural Elections: Some Evidence from India

NCAER Working Papers on Decentralisation and Rural Governance in India ALIGNING WITH ONE’S OWN: Private Voting and Public Outcomes in Rural Elections: Some Evidence from India Raghbendra Jha Hari K. Nagarajan Kailash C. Pradhan No 10 December 2012 ALIGNING WITH ONE’S OWN: Private Voting and Public Outcomes in Rural Elections: Some Evidence from India# Raghbendra Jha Hari K. Nagarajan Kailash C. Pradhan Australian National University, NCAER, New Delhi NCAER, New Delhi Canberra Abstract Identity based voting is a second best solution adopted by households to minimize the negative effects of one’s own identity and (or) identity based coalitions. If a significant source of household welfare is one’s identity or, membership in ethnically defined groups, then politics that results will be parochial in nature. In parochial politics voting along ethnic lines becomes a significant tool for gaining welfare or to discipline the elected representatives. Using newly available data from rural India, we establish that identity based voting will lead to enhanced participation in welfare programs and increased consumption growth. The paper is able to able to show that identity based voting results from the externalities derived from membership in social and information networks, and such voting by enhancing participation in welfare programs leads to significant increases in household consumption growth. Key Words: Identity Based Voting, Panchayats, Decentralization, Devolution JEL Classification: D7, D72, D73 # This paper is part of the IDRC–NCAER research program on “Building Policy Research Capacity for Rural Governance and Growth in India” (grant number 105223). We wish to thank Hans Binswanger and Andrew Foster for comments on earlier drafts. -

Muslim Politics and the 2020 Bihar Election

TIF - Muslim politics and the 2020 Bihar Election JULIEN LEVESQUE December 4, 2020 Asaduddin Owaisi with the newly elected AIMIM MLAs from Bihar | AIMIM (Facebook) The story of the Muslim vote in Bihar is not the triumph of the AIMIM, but the strong desire of the Muslim voter in both majority and minority areas across the state to express herself against the BJP and its allies. In the final outcome of the Bihar assembly elections, what drew attention to some of the successful Muslim candidates was the fact that the All India Muslim Ittehad-ul Muslimeen (AIMIM) won five seats in the north- eastern Seemanchal region, where Muslims form about half of the population (from 77.5% in Jokihat to 38% in Araria). However, the AIMIM’s MLAs represent less than a third of the 19 Muslims who were elected to the assembly this year. This shows that there is more to Muslim political participation in Bihar than the AIMIM’s breakthrough. This article offers a typology of the forms of political dynamics among Muslims in Bihar — the basic idea being that Muslim political dynamics are different in minority and majority areas. Page 1 www.TheIndiaForum.in December 4, 2020 Muslim (majority) politics: The AIMIM’s foray in Seemanchal When looking at Muslim political participation in Bihar, one of the interesting characteristics of the state is that it includes both Muslim minority and majority (or near-majority) areas. This leads to two distinct political dynamics. In areas where they are not in a majority, Muslims seem subject to a kind of minority syndrome and thus more concerned with security than with collective assertion. -

Paper Download

Culture survival for the indigenous communities with reference to North Bengal, Rajbanshi people and Koch Bihar under the British East India Company rule (1757-1857) Culture survival for the indigenous communities (With Special Reference to the Sub-Himalayan Folk People of North Bengal including the Rajbanshis) Ashok Das Gupta, Anthropology, University of North Bengal, India Short Abstract: This paper will focus on the aspect of culture survival of the local/indigenous/folk/marginalized peoples in this era of global market economy. Long Abstract: Common people are often considered as pre-state primitive groups believing only in self- reliance, autonomy, transnationality, migration and ancient trade routes. They seldom form their ancient urbanism, own civilization and Great Traditions. Or they may remain stable on their simple life with fulfillment of psychobiological needs. They are often considered as serious threat to the state instead and ignored by the mainstream. They also believe on identities, race and ethnicity, aboriginality, city state, nation state, microstate and republican confederacies. They could bear both hidden and open perspectives. They say that they are the aboriginals. States were in compromise with big trade houses to counter these outsiders, isolate them, condemn them, assimilate them and integrate them. Bringing them from pre-state to pro-state is actually a huge task and you have do deal with their production system, social system and mental construct as well. And till then these people love their ethnic identities and are in favour of their cultural survival that provide them a virtual safeguard and never allow them to forget about nature- human-supernature relationship: in one phrase the way of living. -

2018070953.Pdf

List of Block Health Manager Candidates Highest Qualification (Eligiblity - Category Experience Age as on Sex Caste Name Digree/Diploma in Total Experience in (Gen/BC/EBC/ Religion Permanent Address Corespondence Address (Eligiblity - Minm 2 Yrs. in Date of Birth 01/01/2016 (M/F/T) (Subcaste) Hospital Health Sector Sl. No. Name of the Candidate Father's Name BCF/SC/ST) Health Sector) (DD/MM/YYYY) Management/Health Management/MBA) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1- ,p0vkbZ0Hkh0@,sM~l & dfVgkj 05 vizSy] 2009 ls 10 twu] 2010 xzke$iks0 & clkSuk] 2- fcgkj ,sM~l daVªksy ftyk & lgjlk xzke$iks0 & clkSuk] ,e0,l0MCyw0] vLirky lkslkbZVh@vkbZ0Mh0;w0] dfVgkj & 1 jktw jkt dqekj feJk Jh lqHkk"kpUnz feJk 01-04-1983 32 o"kZ 09 ekg iq:"k lkekU; fgUnq 6 o"kZ 10 ekg 11 fnu eks0 ua0 & 9060961234] ftyk & lgjlk izca/kuA 20 twu] 2010 ls 31 ekpZ] 2012 9576843580 3- fcgkj jkT; ,sM~l lkslkbZVh] iVuk & ,l0Vh0Mh0 dkWmalsyj lnj vLirky] dfVgkj 01 vDVqcj] 2012 ls vcrdA gkml u0 & 23] MkDVj~l dkWyksuh] 1- eSDl ykbZQ Mk;XuksfLVd ,.M 27 o"kZ 11 ekg xzke & isykiqj] iks0$Fkkuk & 2 eks0 fnyuokt eks0 eUuku vkye 15-01-1988 iq:"k fiNM+k oxZA lwjtkiqjh eqfLye dadM+ckx] iVuk ,e0ch0,0 ¼vLirky izca/ku½ fjlpZ lsaVj & dadM+ckx] iVuk 1 o"kZ 07 ekg 17 fnu cfy;k csykWu] ftyk & dfVgkj eks0 ua0 & 9717891776] 7765083912 01 twu] 2014 ls vcrd Qsjh jksM] cjkjh] cjkjh] Hkkxyiqj& Qsjh jksM] cjkjh] cjkjh] Hkkxyiqj& 35 o"kZ 02 ekg 3 eks0 bZlk eks0 eqlk 15-10-1980 iq:"k vuqiyC/k eqfLye 812003 812003 ,e0ch0,0 vuqiyC/k ¼LokLF; {ks=½ 17 fnu eks0 & 7461963309 eks0 & 7461963309 37 o"kZ 05 ekg xzke$iks0 &:ikSyh] -

Bottor of ^Dtla^Opdp Rn SOCIOLOGY

FERTILITY TRENDS AND POPULATION POLICY IN NORTH EAST BIHAR THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF Bottor of ^dtla^opdp rN SOCIOLOGY BY SH^KEEL AHMAD Under the Supervision of Dr. Noor Mohammad Professor and Chairman DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1987 fHESISSEtro/^ s III' "^ •5l* ^ T3645 C0NTSI3TS IBSL pr«f«c« iv CHAPTER «• Z t Introduction 1-152 populat^Lon Policy 33 family Planning undsr tha Pisat Fiva Yaar Plan 19S1*S»6 31 raatily Planning undar tha laeond fiya Year Plan 19$6*6l 39 Family planning undac tha Third Fiva Yaar Plan 1961-66 62 Family Planning tinder tha Annual plans 1966*69 71 Family Planning undar tha Fourth Fiva Yaar Plan 1969-74 73 Family Planning undar tha Fifth Five Year Plan 1974-79 86 Family Planning under the Sixth Five Year Plan 19B0-8S 106 organisational iiat-t^ for Family PlflLhning at tha Centre 116 organisational set-up for Family planning at State Level 117 organisational £»et-\qp for Family Planning at District Lcnrel 117 Merits and Demerits of Indian population policy 122 CHAPTSR - II I Methodology 153-1' stateiaant of the Problem 133 AiiBS end Objectives of the study 157 Scope of the Study 158 Area of the study I6I Purnia District 164 saharsa District 167 Katihar District vV 167 Tools of study '*h, 173 1. CHAiiTiUi - III t i^Iigious Coa|iosition 175-19 Religious Composition of'^^india 175 Religious C<Mnposition of Bihar 133 Religious aniposition of Purnia 187 Religious Coaqposition of Saharsa 189 Religious Cofli|)08ition of Katihar 191 CHAPIER - IV t Age structure 19^-21 The -

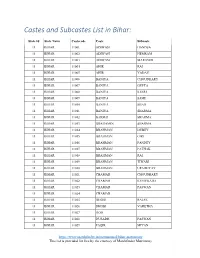

Castes and Subcastes List in Bihar

Castes and Subcastes List in Bihar: State Id State Name Castecode Caste Subcaste 11 BIHAR 11001 ADIWASI HANDSA 11 BIHAR 11002 ADIWASI HEMRAM 11 BIHAR 11003 ADIWASI MARANDI 11 BIHAR 11004 AHIR RAI 11 BIHAR 11005 AHIR YADAV 11 BIHAR 11006 BANIYA CHOUDHARY 11 BIHAR 11007 BANIYA GUPTA 11 BIHAR 11008 BANIYA KESRI 11 BIHAR 11009 BANIYA SAHU 11 BIHAR 11010 BANIYA SHAH 11 BIHAR 11011 BANIYA SHARMA 11 BIHAR 11012 BARHAI SHARMA 11 BIHAR 11013 BRAHAMIN SHARMA 11 BIHAR 11014 BRAHMAN DUBEY 11 BIHAR 11015 BRAHMAN GIRI 11 BIHAR 11016 BRAHMAN PANDEY 11 BIHAR 11017 BRAHMAN PATHAK 11 BIHAR 11018 BRAHMAN RAI 11 BIHAR 11019 BRAHMAN TIWARI 11 BIHAR 11020 BRAHMAN UPADHYAY 11 BIHAR 11021 CHAMAR CHOUDHARY 11 BIHAR 11022 CHAMAR KUSHWAHA 11 BIHAR 11023 CHAMAR PASWAN 11 BIHAR 11024 CHAMAR 11 BIHAR 11025 DHOBI RAJAK 11 BIHAR 11026 DHOBI VARETHA 11 BIHAR 11027 DOM 11 BIHAR 11028 DUSADH PASWAN 11 BIHAR 11029 FAQIR MIYAN https://www.matchfinder.in/matrimonial/bihar-matrimony This list is provided for free by the courtesy of Matchfinder Matrimony 11 BIHAR 11030 GUND 11 BIHAR 11031 HALWAI SAHU 11 BIHAR 11032 HARI RAI 11 BIHAR 11033 HARI 11 BIHAR 11034 HUSSAIN 11 BIHAR 11035 JULAHA ANSARI 11 BIHAR 11036 KAHAR PRASAD 11 BIHAR 11037 KAHAR RAWAT 11 BIHAR 11038 KAHAR 11 BIHAR 11039 KAYASTH SRIVASTAV 11 BIHAR 11040 KOERI KUSHWAHA 11 BIHAR 11041 KOERI MAURIYA 11 BIHAR 11042 KOERI RAI 11 BIHAR 11043 KULHAIYA ALAM 11 BIHAR 11044 KULHAIYA 11 BIHAR 11045 KUMHAR PRJAPATI 11 BIHAR 11046 KUMHAR 11 BIHAR 11047 KUMHAR 11 BIHAR 11048 LOHAR PRJAPATI 11 BIHAR 11049 LOHAR SHARMA 11 BIHAR -

Download Full Length Paper

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 11 Issue 02, February 2021 ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gate as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A Ethnography of Kulhaiya People in Araria – Holistic Approach (1) Tanweer Alam Ph.D. Research scholar, Department of TT & NFE (IASE), Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, [email protected] (2)Prof. Kartar Singh Department of TT&NFE (IASE), Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, [email protected] Abstract: kulhaiya community is economically marginalized communities. The Kulhaiya community resides in the northeastern part of Bihar. The Kulhaiya are mainly found in Araria, Kishanganj, Purnia and Katihar districts. A sizeable population also resides in Morang district of Nepal. After independence many sincere and concreted steps were made for the economic and educational development of marginalized communities. Despite these efforts and endeavor the educational status of Kulhaiyas is much lower than the any other communities in India. According to 2011 census the total population of this community is 25 lakh. The Kulhaiya population is concentrated largely in Araria, Purnea, Katihar and Kishanganj district of Bihar.According to 2011 census, kulhaiyas constitute 42% in Araria district, 43 percent in Purnia district, 32 percent in Katihar district and 26 percent in Kishanganj district. Physically they are classified as Hadhrami-origin tribe of Yemen settled who came as mercenaries to North-east Bihar via Sindh and Kutchh, on the invitation of the Bengal Nawab. -

The Making of EBC in Bihar: from Karpoori to Nitish

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 The Making of EBC in Bihar: From Karpoori to Nitish DR. Nagendra Prasad Verma Associate Professor Department of History P. G. Centre Rajendra College, Chapra (Jai Prakash University, Chapra) Bihar- 841301 This study is an attempt to portray the trajectory of the rise and growth of EBCs of Bihar in historical perspectives. It will also look into the process of transformation of EBCs from ‘Class- in -itself’ to ‘Class- for- itself’. The Karpoori Thakur Ministry’s reservation policy is indicative of a sea-change in the structure of Bihar’s political sociology. Despite some hiatus, the coming into power of Lalu Prasad led JD Government, the process of backward dominance in Bihar’s politics accelerated. However, the EBCs failed to keep pace with the OBCs, and a long gap became perceptible between them, though the former also moved ahead. Nitish Government has taken several steps to fill the gap to bring EBCs into mainstream. Keywords: EBC, Annexure I & II, Class- in -itself, Class- for- itself, Mungerilal Commission. This study is an attempt to portray the trajectory of the rise and growth of EBCs in historical perspectives. It will also look into the process of transformation of EBCs from ‘Class- in -itself’ to ‘Class- for- itself’. The Karpoori Thakur Ministry’s reservation policy is indicative of a sea-change in the structure of Bihar’s political sociology - The Volume XII, Issue X, 2020 Page No: 576 Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Forwards or twice-born caste groups that had been dominant in Bihar since independence and before are being replaced by the Backward Castes as the dominant stratum in the state. -

Castes and Subcastes List in India

Castes and Subcastes List in India: State Id State Name Castecode Caste Subcaste 1 KERALA 1001 ACHARI KONGU VELLALA 1 KERALA 1002 ACHARI VISHWAKARMA 1 KERALA 1003 ACHARI 1 KERALA 1004 ADI DRAVIDA PARAYA 1 KERALA 1005 AENTELUR ROMAN CATHOLIC 1 KERALA 1006 AMBATTAN 1 KERALA 1007 ARAYAN DEVARA 1 KERALA 1008 ARAYAN 1 KERALA 1009 BARBAR 1 KERALA 1010 BRAHMAN BHATT 1 KERALA 1011 BRAHMAN IYER 1 KERALA 1012 BRAHMAN 1 KERALA 1013 CATHOLIC LATIN CATHOLIC 1 KERALA 1014 CATHOLIC PULAYA 1 KERALA 1015 CATHOLIC ROMAN CATHOLIC 1 KERALA 1016 CATHOLIC SYRIAN 1 KERALA 1017 CATHOLIC 1 KERALA 1018 CHAKKILIYAN AMMA 1 KERALA 1019 CHAKKILIYAN 1 KERALA 1020 CHERUMAN IRAYA 1 KERALA 1021 CHERUMAN KANAKKAN 1 KERALA 1022 CHERUMAN 1 KERALA 1023 CHETTIAR CHAKKA 1 KERALA 1024 CHETTIAR TELUGU 1 KERALA 1025 CHETTIAR TELUGU CHETTIAR 1 KERALA 1026 CHETTIAR VANIAR 1 KERALA 1027 CHETTIAR 1 KERALA 1028 CHRISTIAN CATHOLIC 1 KERALA 1029 CHRISTIAN CHRISTIAN 1 KERALA 1030 CHRISTIAN ROMAN CATHOLIC 1 KERALA 1031 CHRISTIAN 1 KERALA 1032 DHOBI https://www.matchfinder.in This list is provided for free by the courtesy of Matchfinder Matrimony 1 KERALA 1033 DWEEPARA 1 KERALA 1034 EZHAVA AMMELU 1 KERALA 1035 EZHAVA CHETTI 1 KERALA 1036 EZHAVA EZHAVA 1 KERALA 1037 EZHAVA GHIYAIU 1 KERALA 1038 EZHAVA HARIJAN 1 KERALA 1039 EZHAVA KONGU VELLALA 1 KERALA 1040 EZHAVA MENON 1 KERALA 1041 EZHAVA PANKAR 1 KERALA 1042 EZHAVA PILLAI 1 KERALA 1043 EZHAVA THEYAHAN 1 KERALA 1044 EZHAVA THIYA 1 KERALA 1045 EZHAVA VANIKA 1 KERALA 1046 EZHAVA VANIYAN 1 KERALA 1047 EZHAVA VARRER 1 KERALA 1048 EZHAVA VATHI 1 KERALA 1049 EZHAVA 1 KERALA 1050 EZHUTHACHAN 1 KERALA 1051 G.S.B. -

Ex Gaz. 269.Doc

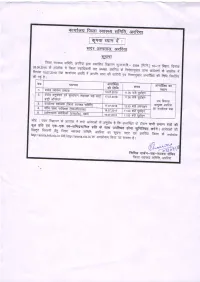

िनबंधन सं या पी0ट/0-40 Bबहार गजट असाधारण अंक Bबहार सरकार ारा ूकािशत 313131 येयें ंठंठ 1119341934 (((श(शशश0000)))) (((सं(संसंसं0000 पपपटनापटना 222692696969)) पपपटनापटनाटना,,,, वृहःपपित ितितितवारवारवारवार,,,, 212121 जूनजूनजून 2012 i=kad 111111@fo0&2&fi0o0vk0&6@2005&11 @fo0&2&fi0o0vk0&6@2005& lkñizñ&lkñizñ&87018701 lkekU; iz'kklu foHkkx &&&&&&&&&& izs"kd] uohupUnz >k] ljdkj ds la;qDr lfpoA lsok eas] lHkh iz/kku lfpo@lfpoA lHkh ize.Myh; vk;qDrA lHkh ftyk inkf/kdkjhA lfpo] fcgkj yksd lsok vk;ksx] iVukA lfpo] deZpkjh p;u vk;ksx] iVukA ijh{kk fu;a=d] fcgkj la;qDr izos'k izfr;ksfxrk ijh{kk Ik"kZn] iVukA lnL; lfpo] fiNMs+ oxksZ ds fy, jkT; vk;ksx] iVukA lfpo] vfr fiNM+s oxksZ ds fy, jkT; vk;ksx] fcgkj] iVukA lfpo] jkT; egknfyr vk;ksx] iVukA iVuk&15] fnukad 18 twu] 2012 fo"k;%&fcgkj inksa ,oa lsokvksa dh fjfDRk;ksa esa vkj{k.k ¼vuqlwfpr tkfr;ksa@vuqlwfpr tutkfr;ksa ,oa vU; fiNM+s oxksZa ds fy,½ ¼vf/kfu;e&1991½ fcgkj vf/kfu;e&3@1992 dh vR;ar fiNM+s oxkasZ dh lwph ¼vuqlwph&1½ ,oa fiNM+s oxksZa dh lwph ¼vuqlwph&2½ dk lEizs"k.kA egksn;] funs'kkuqlkj mi;qZDr fo"k; ds laca/k esa dguk gS fd rkRdkyhu dkfeZd ,oa iz'kklfud lq/kkj foHkkx ¼lEizfr lkekU; iz'kklu foHkkx½ ds ifji= la[;k 2927] fnukad 21-07-2010 }kjk jkT; ds vR;Ur fiNM+s oxksZa 2 Bबहार गजट (असाधारण ), 21 जून 2012 ,oa fiNM+s oxksZa dh lwph ifjpkfyr dh xbZ gSA dkyØe ls fcgkj vf/kfu;e 3@1992 esa vf/klwfpr vR;Ur fiNM+s oxksZa ,oa fiNM+s oxksZ dh lwph esa la'kks/ku fd;k tkrk jgk gS] ftls tu lk/kkj.k dh tkudkjh ds fy, iqu% ifjpkfyr fd;s tkus dh vko';drk eglwl dh xbZ gSA 2- mDRk ifjis{; esa fcgkj vf/kfu;e