West Bengal West Bengal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetic Structure of Tribes of Bihar-Proposed Easy

ANTHROPOLOGICAL GENETICS Int. J. Mendel, Vol. 35(1-2), 2018 & 36(1-2), 2019 183-186 ISSN0970-9649 GENETIC STRUCTURE OF TRIBES OF BIHAR-PROPOSED EASY METHODOLOGIES AND SOME NOTABLE CONTRIBUTIONS Indrani Trivedi* and M.P.Trivedi** Key words : Genetic structure, Tribes,Bihar, Proposed methodologies, Notable contributions The gene frequency data are pre-requisite for knowing genetic structure of human population. The variations in gene pool are due to selection, migration, mutation,and genetic drift. There is meagre work available on genetic structure of tribes of Bihar. Some achievements have been highlighted and need more work to reach conclusions. INTRODUCTION We, Homo sapiens are product of biology and culture. We always strive for a better life. Humans migrate from one place to another in response to better habitat and food opportunity. Every individual has its own genetic constitution. Their unique genetic structure help them in fighting diseases and finally adaptation. The genetic structure of human populations is significant to study ethnic relationship. Encoded history of migration and remote past are carried in the genes of modern human population. Human populations differ genetically in varying proportions of the alleles of various sets. Biological variations in humans are related to the ethnic and ecological background of population. The genetic similarities indicate common origin. The variations in gene pool may be due to mutation, selection, migration and genetic drift. The gene pool is not a simple sum of genes, but is a dynamic system which is hierarchically organized and which maintains the memory of past events in the history of populations.The gene frequency data are pre-requisite for knowing genetic structure of human populations. -

HINDU PATRIKA Published Monthly Vol 05/2010 May 2010

! HINDU PATRIKA Published Monthly Vol 05/2010 May 2010 RATTAN LAW FIRM, LLC Attorneys-at-Law § General Business & Contract Law § Buy-Sell Agreements & Negotiations § Formation of Corporations, LLC’s, Partnerships § Business Dispute Litigation § Residential & Commercial Real Estate Law § Bankruptcy § Wills & Trusts § Powers of Attorney § Probate & Estate Administration Next month Patrika cover can be your kids painting details on page 17 For more information contact Manu K. Rattan, Esq. Hindu Temple & Cultural Center of Kansas City 2100 Silver Avenue A NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION TEMPLE HOURS 6330 Lackman Road Kansas City, KS 66106 Day Time Aarti Shawnee, KS 66217-9739 Mon - Fri 10:00am-12:00pm 11:00am (913) 432-0660 http://www.htccofkc.org Mon - Fri 5:00pm-9:00pm 8:00pm www.mykclawyer.com/rattan Sat & Sun 9:00am-9:00pm 12:00pm Tel: (913) 631-7519 (Temple) Sat & Sun 8:00pm Tel: (913) 962-9696 (Priest Shrinivas) Tel: (913) 749-2062 (Priest Atulbhai) Hindu Patrika May 2010 2 Dear Ones extracurricular activities and commitments, the executive committee As you may all have heard about the upcoming World Peace Maha Yagna at the Hindu Temple that starts from the 7th through the 16th. The Maha Yagna is on painstakingly planned the event for hours. Great Job YGKC! the 16th. HTCC has embarked on an ambitious one of a kind religious event in HTCC is planning for a family picnic on June 19, please standby for more North America. This event will bring not only global peace and harmony but information. also unity, prosperity & joy to the world, and also to each family. -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ______VOLUME LXIV NO.3 SEPTEMBER 2018 ______

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ________________________________________________________ VOLUME LXIV NO.3 SEPTEMBER 2018 ________________________________________________________ LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI ___________________________________ The Journal of Parliamentary Information __________________________________________________________________ VOLUME LXIV NO.3 SEPTEMBER 2018 CONTENTS Page EDITORIAL NOTE ….. ADDRESSES - Address by the Speaker, Lok Sabha, Smt. Sumitra Mahajan at the Inaugural Event of the Eighth Regional 3R Forum in Asia and the Pacific on 10 April 2018 at Indore ARTICLES - Somnath Chatterjee - the Legendary Speaker By Devender Singh Aswal PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES … PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL … DEVELOPMENTS SESSIONAL REVIEW State Legislatures … RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST … APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted by the … Parliamentary Committees of Lok Sabha during the period 1 April to 30 June 2018 II. Statement showing the work transacted by the … Parliamentary Committees of Rajya Sabha during the period 1 April to 30 June 2018 III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures … Of the States and Union Territories during the period 1 April to 30 June 2018 IV. List of Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament … and assented to by the President during the period 1 April to 30 June 2018 V. List of Bills passed by the Legislatures of the States … and the Union Territories during the period 1 April to 30 June 2018 VI. Ordinances promulgated by the Union … and State Governments during the period 1 April to 30 June 2018 VII. Party Position in the Lok Sabha, the Rajya Sabha … and the Legislatures of the States and the Union Territories ADDRESS BY THE SPEAKER, LOK SABHA, SMT. SUMITRA MAHAJAN AT THE INAUGURAL EVENT OF THE EIGHTH REGIONAL 3R FORUM IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC HELD AT INDORE The Eighth Regional 3R Forum in Asia and the Pacific was held at Indore, Madhya Pradesh from 10 to 12 April 2018. -

Jamia Journal of Education (An International Biannual Publication)

ISSN 2348 3490 Jamia Journal of Education A PEER REVIEWED REFEREED INTERNATIONAL BIANNUAL PUBLICATION VOLUME 6 NUMBER 02 MARCH 2020 ISSN 2348 3490 JAMIA JOURNAL OF EDUCATION A Peer Reviewed Refereed International Biannual Publication Volume 6 Number 2 March 2020 FACULTY OF EDUCATION JAMIA MILLIA ISLAMIA NEW DELHI – 110025 INDIA ISSN 23483490 JAMIA JOURNAL OF EDUCATION A Peer Reviewed Refereed International Biannual Publication Volume 6 Number 2 March 2020 Chief Patron Prof. Najma Akhtar Vice-Chancellor, JMI ADVISORY BOARD Ahrar Husain : Professor, Honorary Director (Academics), CDOL & former Dean, F/O Education, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi [email protected] Anita Rastogi : Professor, Former Head, Deptt. of Educational Studies, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi [email protected] Bharati Baveja : Department of Education and Women Studies and Development & Former Head & Dean, Faculty of Education, University of Delhi, Delhi [email protected] Disha Nawani : Professor & Dean, School of Education, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai [email protected] Gimol Thomas George : Director of Assessment, Nova South Eastern University-3200, South University Drive Fort, Lauderdale, Florida USA [email protected] Ilyas Husain (Rtd.) : Professor, Ex- Pro-Vice Chancellor, Jamia Millia Islamia & Former Dean, Faculty of Education, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi [email protected] Joanna Madalinska-Michalak : Professor, University of Warsaw, Poland [email protected] Kutubuddin Halder : Professor & Head, Department of Education, -

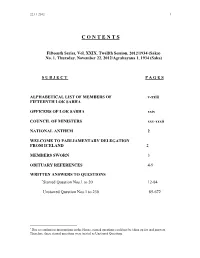

C O N T E N T S

22.11.2012 1 C O N T E N T S Fifteenth Series, Vol. XXIX, Twelfth Session, 2012/1934 (Saka) No. 1, Thursday, November 22, 2012/Agrahayana 1, 1934 (Saka) S U B J E C T P A G E S ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF v-xxiii FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA OFFICERS OF LOK SABHA xxiv COUNCIL OF MINISTERS xxv-xxxii NATIONAL ANTHEM 2 WELCOME TO PARLIAMENTARY DELEGATION FROM ICELAND 2 MEMBERS SWORN 3 OBITUARY REFERENCES 4-9 WRITTEN ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ∗Starred Question Nos.1 to 20 12-84 Unstarred Question Nos.1 to 230 85-672 ∗ Due to continuous interruptions in the House, starred questions could not be taken up for oral answers. Therefore, these starred questions were treated as Unstarred Questions. 22.11.2012 2 STANDING COMMITTEE ON HOME AFFAIRS 673 164th Report MATTERS UNDER RULE 377 674-692 (i) Need to increase the wages of teachers of Kasturba Gandhi Awasiya Balika Vidyalaya and also regularise their appointment Shri Harsh Vardhan 674 (ii) Need to set up a big Thermal Power Plant instead of many plants, as proposed, for various places in the Vidarbha region of Maharashtra Shri Vilas Muttemwar 675-676 (iii) Need to address issues concerning Fertilizers and Chemicals Travancore Ltd. (FACT) in Kerala Shri K.P. Dhanapalan 677-678 (iv) Need to provide financial assistance for upgradation of the stretch of NH No. 212 passing through Bandipur forest, Gundlupet town limits and Nanjangud to Mysore in Karanataka Shri R. Dhruvanarayana 679 (v) Need to augment production of orange in Vidarbha region of Maharashtra by providing financial and technical support to the farmers of this region Shri Datta Meghe 680 (vi) Need to provide constitutional status to National Commission for Backward Classes to strengthen existing safeguards for Backward Classes and to take additional measures to promote their welfare Shri Ponnam Prabhakar 681-682 22.11.2012 3 (vii) Need to restore the originating and terminating station for train No. -

Private Voting and Public Outcomes in Elections in Rural India [PDF, 166KB

ASARC Working Paper 2011/09 ALIGNING WITH ONE’S OWN: Private Voting and Public Outcomes in Elections in Rural India# Raghbendra Jha Hari K. Nagarajan Kailash C. Pradhan Australian National University, NCAER, New Delhi NCAER, New Delhi Canberra Abstract This paper has the objective of showing that identity based voting will lead to improvements in household welfare through increased access to welfare programs. Using newly available data from rural India, we establish that identity based voting will lead to enhanced participation in welfare programs and increased consumption growth. We also show that consumption growth is retarded if households do not engage in identity based voting. Using 3 stage least squares, we are able to show that identity based voting results from the externalities derived from membership in social and information networks, and such voting by enhancing participation in welfare programs leads to significant increases in household consumption growth. Key Words: Identity Based Voting, Panchayats, Decentralization, Devolution JEl Classification: D7, D72, D73 # This paper is part of the IDRC–NCAER research program on “Building Policy Research Capacity for Rural Governance and Growth in India” (grant number 105223). We wish to thank Hans Binswanger and Andrew Foster for comments on earlier drafts. The usual caveat applies. Raghbendra Jha, Hari K Nagarajan & Kailash C Pradhan Right wing academic force — particularly a group of sociologists and anthropologists — advised the Bharatiya Janata Party led National Democratic Alliance Government not to go for caste based census in 2001 as it would go against the ruling upper castes and communities. It is fallacious to argue that society will get further divided if the population of each caste is known to the policy maker and public…It is true that we cannot distribute everything based on caste. -

Standing Committee Report on 115Th Constitution Amendment Bill

73 STANDING COMMITTEE ON FINANCE (2012-13) FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA MINISTRY OF FINANCE (DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE) THE CONSTITUTION (ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH AMENDMENT) BILL, 2011 SEVENTY THIRD REPORT LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI August, 2013, Sravana, 1935 (Saka) 1 SEVENTY THIRD REPORT STANDING COMMITTEE ON FINANCE (2012-2013) (FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA) THE CONSTITUTION (ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH AMENDMENT) BILL, 2011 Presented to Lok Sabha on 7 August, 2013 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 7 August, 2013 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI August, 2013, Sravana, 1935 (Saka) 2 CONTENTS Page Nos. Composition of the Committee………………………………………. Introduction……………………………………………………………. REPORT PART -I I. GST Design 1 II. Salient features of the Bill 7 III. Impact of GST on : (a) Economy 11 (b) Prices 15 (c) Consumer prices – International experiences 17 (d) Producing States and Consuming States 18 (e) MSME and Employment Generation 19 PART-II IV. Issues relating to Amendment Bill 22 (a) Power to make laws with respect to Goods & Services Tax 22 (b) Integrated Goods and Services Tax (IGST) 24 (c) GST Council 26 (d) Goods & Services Tax Dispute Settlement Authority 32 (e) Declared Goods (Article 286) 35 (f) Goods and Services Tax (Article 366) 36 (g) Amendment of Sixth Schedule to the Constitution 40 (h) Amendment of Seventh Schedule to the Constitution 41 (i) Transitional Provision 44 V. Administration and IT Mechanism 45 VI. Compensation Mechanism 46 VII. GST Monitoring Cell 47 VIII. Alternative to GST Model 48 IX. Latest position of the Empowered Committee of State 50 Finance Ministers on the provisions of the Bill X. Consensus between Centre and States on GST Design and 53 CST Compensation Part-III Observations / Recommendations 55 3 APPENDICES I. -

Ram Janma Bhoomi Facts

1 “OM” Jai Sri Ram! Facts About Sri Ram Janma-Bhoomi Liberation Movement 01. Points of dispute (i) The Ayodhya dispute is not any ordinary temple-mosque dispute as the Temple of Nativity of Sri Ram is not just any other temple! (ii) It is a struggle to reclaim and regain the haloed Native Land/Birthplace of Bhagwan, and this Native Land is a Deity in itself and there can be no splitting up or division of the Deity. Ramlala Virajman (Infant Sri Ram sitting at His Birthplace) at His Native Land – is a perpetual minor and a juridical person – a legal entity – having a distinct identity and legal rights and obligations under the law. None else can have ownership rights over Bhagwan’s property. (iii) The birthplace is non-exchangeable. It cannot be swapped, bartered, sold or donated! (iv) The entire dispute is over about 1460 square yards (1209.026 Square Meter) of land – the length-width of which is maximum 140 X 100 feet. The 70 acres of land acquired by the Government of India is separate from it and is with the Government of India over which no lawsuit is pending in court. (v) The entire site under consideration in the court is that of Ramlala (Infant Ram) Virajman. It is the Place of Birth, Place of Pastimes, playing field and recreational area of Bhagwan. Describing the significance of this place, the Skanda Purana, written thousands of years ago, says that the Darshan (discerning/sighting) of the haloed birthplace of Sri Ram is liberating. (vi) Temples of adorable Deities of any community can be built in many places in the country, statues of great men can be put up at many places, but their place of manifestation/birth would be located at one place and that can never be dislocated or put out of place. -

ITIHASAS ‘IT HAPPENED THUS’ the Two Great Epics of India

ITIHASAS ‘IT HAPPENED THUS’ The two great epics of India RAMAYANA THE ADI KAVYA The significance of the Ramayana The Ramayana is the first of the two great Itihasas of India. It was written by sage Valmiki. It consisted of 24,000 verses. It is considered by some as mythology. But to millions of Indians, it is history and offers a guide to right living. The Ramayana is considered by all Hindus as an embodiment of the Vedas, and that Lord Vishnu himself came upon earth to show people how life is to be lived. The greatness of Dharma shines in the life of Rama. The story of Rama On the banks of the Sarayu river, stood the beautiful city of Ayodhya, the capital of the kingdom of Kosala. The people of Ayodhya were peace loving and happy. No one was ignorant or poor. Everyone had faith in God and read the scriptures daily. But Dasaratha, the king, was unhappy. He was getting old and he didn’t have a son to inherit his throne. One day the king called upon his Chief advisor, Vasishtha. He said. "I am growing old. I long for a son, a son who will take my place on the throne."The priest knew all too well that his king needed to have a son. He replied, "Dasaratha, you will have sons. I shall perform a sacred rite to please the gods." At the same moment, the gods were growing more and angrier with Ravana, the ruler of the rakshasas, or demons. Ravana was no ordinary demon. -

Jai Shri Ram CD

Jai Shri Ram CD Track 1 jy ra3veNd/ srkar kI, jy sIta sukumar kI | jai ra[ghavendra saraka[ra ki[, jai si[ta[ sukuma[ra ki[ All glories to Lord Ram and to the gentle princess Sita. jy ram lXm8 jankI, su0a rr…………pp rs `an kI | jai ra[ma laks>man>a ja[naki[, ssudha[udha[ ru[pa rasa kha[nakha[na ki[ All glories to Ram, Lakshman and Janaki, the treasure-house of nectar and beauty. jy jy raja ram kI, p/em rr…………pp rs 0am kI | jai jai ra[ja[ ra[ma ki[, prema ru[pa rasa dha[ma ki[ All glories to Raja Ram, the treasure-house of love, beauty and sweetness. jy ra3veNd/ srkar kI, jy jy jy pvn kumar kI || jai ra[ghavendra saraka[ra ki[, jai jai jai pavana kuma[ra ki[ All glories to Shri Ram and to Pavan Kumar, Hanuman. Track 2 Ab p/-u kk››››papa krhu yeih -a%tI | sb tij -jn krO& idn ratI ||| ||| aba prabhu kr>pa[ karahu yehi bha[m>ti[, saba taji bhajana karaum> dina ra[ti[ Lord, bestow grace on me that I may chant Your name day and night. sa0k isis²²²² ivmuivmuÆÆÆÆ wdasI | kiv koivd kk›››tt›ttßßßß sNyasI || sa[dhaka siddha vimukta uda[si[, kavi kovida kr>tajn`a sannsannya[si[ya[si[ Whether an aspiring devotee or a realized one; a liberated soul or a detached one; a poet, a scholar, one who knows the secrets of Karma or a renunciate…. jogI sUr sutaps GyanI | 0mR inrt p&i6t ivGyanI || jogi[ su[ra suta[pasa jn`a[ni[, dharma niraniratata pand>itapand>ita vijn`a[ni[ ….a yogi, a man of valor, an ascetic, a pundit or a man of knowledge……. -

Ramayan Ki Kathayen, Pandemic and the Hindu Way of Life and the Contribution of Hindu Women, Amongst Others

Hindu Sevika Samiti (UK) Mahila Shibir 2020 East and South Midlands Vibhag FOREWORD INSPIRING AND UNPRECEDENTED INITIATIVE In an era of mass consumerism - not only of material goods - but of information, where society continues to be led by dominant and parochial ideas, the struggle to make our stories heard, has been limited. But the tides are slowly turning and is being led by the collaborative strength of empowered Hindu women from within our community. The Covid-19 pandemic has at once forced us to cancel our core programs - which for decades had brought us together to pursue our mission to develop value-based leaders - but also allowed us the opportunity to collaborate in other, more innovative ways. It gives me immense pride that Hindu Sevika Samiti (UK) have set a new precedent for the trajectory of our work. As a follow up to the successful Mahila Shibirs in seven vibhags attended by over 500 participants, 342 Mahila sevikas came together to write 411 articles on seven different topics which will be presented in the form of seven e-books. I am very delighted to launch this collection which explores topics such as: The uniqueness of Bharat, Ramayan ki Kathayen, Pandemic and the Hindu way of life and The contribution of Hindu women, amongst others. From writing to editing, content checking to proofreading, the entire project was conducted by our Sevikas. This project has revealed hidden talents of many mahilas in writing essays and articles. We hope that these skills are further encouraged and nurtured to become good writers which our community badly lacks. -

Private Voting and Public Outcomes in Rural Elections: Some Evidence from India

NCAER Working Papers on Decentralisation and Rural Governance in India ALIGNING WITH ONE’S OWN: Private Voting and Public Outcomes in Rural Elections: Some Evidence from India Raghbendra Jha Hari K. Nagarajan Kailash C. Pradhan No 10 December 2012 ALIGNING WITH ONE’S OWN: Private Voting and Public Outcomes in Rural Elections: Some Evidence from India# Raghbendra Jha Hari K. Nagarajan Kailash C. Pradhan Australian National University, NCAER, New Delhi NCAER, New Delhi Canberra Abstract Identity based voting is a second best solution adopted by households to minimize the negative effects of one’s own identity and (or) identity based coalitions. If a significant source of household welfare is one’s identity or, membership in ethnically defined groups, then politics that results will be parochial in nature. In parochial politics voting along ethnic lines becomes a significant tool for gaining welfare or to discipline the elected representatives. Using newly available data from rural India, we establish that identity based voting will lead to enhanced participation in welfare programs and increased consumption growth. The paper is able to able to show that identity based voting results from the externalities derived from membership in social and information networks, and such voting by enhancing participation in welfare programs leads to significant increases in household consumption growth. Key Words: Identity Based Voting, Panchayats, Decentralization, Devolution JEL Classification: D7, D72, D73 # This paper is part of the IDRC–NCAER research program on “Building Policy Research Capacity for Rural Governance and Growth in India” (grant number 105223). We wish to thank Hans Binswanger and Andrew Foster for comments on earlier drafts.