Promoting Human Rights in Guatemala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alejandro Giammattei, a New Face Backed by the Same Old Criminal Networks

No Relief in Sight: Alejandro Giammattei, a new face backed by the same old criminal networks January 15, 2020 GHRC President-elect Alejandro Giammattei took office yesterday in Guatemala City. He was never expected to win. After three unsuccessful presidential bids, Giammattei made the runoff Presidential election in August by just one percentage point and only after three candidates had been eliminated through legal actions. His only experience in public office was a 2004-2008 stint as National Prisons Director. In 2010, he was charged with the extrajudicial Alejandro Giammattei became Guatemala’s president January 14; he execution of seven inmates is a champion of retired military officers and extractive industries. under his watch. Though others indicted on related charges were convicted, charges against Giammattei were eventually dismissed by a judge who was later sanctioned as a result of corruption charges, though not in relation to Giamatti’s trial. Giammattei comes to the presidency backed by a group of hard-line former military officers reportedly associated with the sector that opposed the peace process that ended Guatemala’s 36- year civil war. Many are also associated with industries that extract resources from rural communities – often with US, Canadian and European investment - a sector Giammattei has pledged to promote. Some are active members of organizations that have promoted dozens of malicious lawsuits intended to stop the work of public prosecutors, judges, experts, and human rights defenders who contribute to ending impunity for corruption, ongoing human rights abuses, and crimes against humanity carried out during Guatemala’s civil war. Giammattei won 13.9% of the votes in the June 16, 2019 general election, taking second place to former first lady Sandra Torres’ 25.53%. -

The International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala Wola a Wola Report on the Cicig Experience

THE INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION AGAINST IMPUNITY IN GUATEMALA WOLA A WOLA REPORT ON THE CICIG EXPERIENCE THE CICIG: AN INNOVATIVE INSTRUMENT FOR FIGHTING CRIMINAL REPORT ORGANIZATIONS AND STRENGTHENING THE RULE OF LAW 6/2015 THE WASHINGTON OFFICE ON LATIN AMERICA KEY FINDINGS: FORCES THAT OPERATED DURING THE 1960-1996 ARMED CONFLICT. The Guatemalan state did not dismantle these counterinsurgency forces after the 1996 peace accords, allowing for their evolution into organized crime and organized corruption. These transformed entities co-opted state institutions to operate with impunity and achieve their illicit goals. They continue to threaten Guatemalan governability and rule of law. UNIQUE TO GUATEMALA. These parallel structures of repression have morphed into organized crime groups in many countries that have endured armed conflicts. LA COMISIÓN INTERNACIONAL CONTRA LA IMPUNIDAD EN GUATEMALA, CICIG) IS A UNIQUE MODEL OF COOPERATION FOR In contrast to other international mechanisms, the CICIG is an independent investigative entity that operates under Guatemalan law and works alongside the Guatemalan justice system. As a result, it works hand in hand with the country’s judiciary and security institutions, building their capacities in the process. The CICIG has passed and implemented important legislative reforms; provided fundamental tools for the investigation and prosecution of organized crime that the country had previously lacked; and removed public officials that had been colluding -

Guatemala: Corruption, Uncertainty Mar August 2019 Elections

Updated July 5, 2019 Guatemala: Corruption, Uncertainty Mar August 2019 Elections Guatemala held national elections for president, the entire system (2006-2008) during the Óscar Berger 158-seat congress, 340 mayors, and other local posts on administration. Over the past 20 years, he has run for June 16, 2019. The list of candidates on the ballot was president four times with four different parties. In 2010, the finalized one week before voting. Candidates were still CICIG and the attorney general’s office charged him with being ruled ineligible—some due to corruption participating in extrajudicial killings. He was acquitted in allegations—and appealing rulings in early June. Elements 2012 after the courts determined that the case against him of the government allowed some candidates to run and lacked sufficient evidence. impeded the registrations of others. Such uncertainty likely will lead many to question the outcome. UNE won the largest share of congressional seats, but with 44 out of 160 seats, it will still lack a majority. Fifteen Since none of the 19 presidential candidates won the first parties split the other seats, indicating political gridlock is round with more than 50% of the vote, the top two likely to continue and reform likely will be limited. candidates will compete in a second round on August 11. The winner is due to be inaugurated in January 2020. Some Guatemala 2019 Presidential Candidates: 7.6 million Guatemalans have registered to vote in this Determining Who Was Eligible year’s elections. Guatemala’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) is an important part of Guatemala’s democracy, as it organizes Corruption is once again a primary concern for voters. -

Freedom in the World, Guatemala

4/30/2020 Guatemala | Freedom House FREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 Guatemala 52 PARTLY FREE /100 Political Rights 21 /40 Civil Liberties 31 /60 LAST YEAR'S SCORE & STATUS 53 /100 Partly Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. https://freedomhouse.org/country/guatemala/freedom-world/2020 1/18 4/30/2020 Guatemala | Freedom House Overview While Guatemala holds regular elections that are generally free, organized crime and corruption severely impact the functioning of government. Violence and criminal extortion schemes are serious problems, and victims have little recourse to justice. Journalists, activists, and public officials who confront crime, corruption, and other sensitive issues risk attack. Key Developments in 2019 Outgoing president Jimmy Morales attempted to unilaterally shut the UN- backed International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) in January, but his effort was halted by the Constitutional Court. CICIG closed when its mandate expired in September. Alejandro Giammattei was elected president in August after defeating former first lady Sandra Torres in a runoff; he will take office in 2020. In September, Torres was arrested for underreporting contributions for her 2015 presidential bid; her case was continuing at year’s end. In July, Guatemala signed an agreement with the United States that forces asylum seekers traveling through the country to apply there first. The first asylum seeker forced to travel to Guatemala under the agreement was sent from the United States in November. In September, the government declared of a state of siege in the northeast, after three soldiers died in a clash with drug traffickers. -

Luchas Sociales Y Partidos Políticos En Guatemala

LUCHAS SOCIALES Y PARTIDOS POLÍTICOS EN GUATEMALA Sergio Guerra Vilaboy Primera edición, 2016 Escuela de Ciencia Política de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala (ECP) Centro de Estudios Latinoamericanos “Manuel Galich” (CELAT) de la ECP Cátedra “Manuel Galich”, Universidad de La Habana (ULH) ISBN Presentación de la edición guatemalteca Para la Escuela de Ciencia Política (ECP) de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala (USAC), es una gran satisfacción reeditar un libro que, aunque se escribió hace más de treinta años, no ha perdido su vigencia y, además, ahora se actualiza mediante un apéndice que vuelve a poner en evidencia el rigor científico de su autor, el historiador y profesor cubano, Sergio Guerra Vilaboy. A este libro le fue otorgado el Premio Ensayo, de la Universidad de La Habana, en 1983, lo cual expresa la calidad analítica que está en la base del lúcido enfoque que el autor hace de las dinámicas sociales y partidis- tas de nuestra sociedad, cuando recrea momentos decisivos de nuestro proceso conformador como un país que lucha por ser soberano en el marco de la hegemonía y la dominación geopolítica continental de Es- tados Unidos. Para la ECP, publicar una investigación científica como esta en un mo- mento de crisis de Estado (posiblemente la peor de los últimos treinta años) implica contribuir a la generación de un necesario pensamiento crítico que sirva de base para poder ver de nuevo con esperanza hacia el futuro. Nuestra Escuela, por medio de su Centro de Estudios Latinoa- mericanos “Manuel Galich”, reedita este libro necesario con la esperan- za de que, por medio del ejercicio responsable de las ciencias sociales, nuestros estudiantes y profesores desarrollen su criticidad analítica y su organicidad con los intereses de nuestras mayorías. -

Guatemala 2019 Human Rights Report

GUATEMALA 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Guatemala is a multiparty constitutional republic. In 2016 James Ernesto Morales Cabrera of the National Convergence Front party was sworn into office for a four- year term as president. On August 11, Alejandro Giammattei was elected president for a four-year term set to begin on January 14, 2020. International observers considered the presidential election held in 2019 as generally free and fair. The National Civil Police (PNC), which is overseen by the Ministry of Government and headed by a director general appointed by the minister, is responsible for law enforcement and maintenance of order in the country. The Ministry of National Defense oversees the military, which focuses primarily on operations in defense of the country, but the government also used the army in internal security and policing as permitted by the constitution. The defense ministry completed its drawdown of 4,500 personnel from street patrols to concentrate its forces on the borders in 2018. Civilian authorities at times did not maintain effective control over the security forces. Significant human rights issues included: harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; substantial problems with the independence of the judiciary, including malicious litigation and irregularities in the judicial selection process; widespread corruption; trafficking in persons; crimes involving violence or threats thereof targeting lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) persons, persons with disabilities, and members of other minority groups; and use of forced or compulsory or child labor. Corruption and inadequate investigations made prosecution difficult. The government was criticized by civil society for refusing to renew the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala’s (CICIG) mandate, which expired on September 3. -

The End of the CICIG Era

1 The End of the CICIG Era An Analysis of the: Outcomes Challenges Lessons Learned Douglas Farah – President - IBI Consultants Proprietary IBI Consultants Research Product 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...............................................................................................................5 IMPORTANT POINTS OF MENTION FROM LESSONS LEARNED ...........................................7 OVERVIEW AND REGIONAL CONTEXT ....................................................................................8 THE CICIG EXPERIMENT .......................................................................................................... 11 HISTORY ....................................................................................................................................... 14 THE CICIG’S MANDATE ............................................................................................................. 17 THE ROLE AS A COMPLEMENTARY PROSECUTOR OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL ............................. 21 THE IMPACT OF THE CICIG ON CRIMINAL GROUPS ........................................................................ 24 THE CHALLENGES OF THE THREE COMMISSIONERS ........................................................ 27 CASTRESANA: THE BEGINNING ....................................................................................................... 28 DALL’ANESE: THE MIDDLE............................................................................................................ -

The Guatemalan Presidential Election: What Comes Next?

The Guatemalan Presidential Election: What Comes Next? Published: August 1, 2019 What’s the state of the Guatemalan presidential election? With current President Jimmy Morales’ term concluding in 2020, the presidential election is currently underway in Guatemala to determine his successor. The Constitution of Guatemala prohibits incumbent presidents from running for a second term and several prominent political figures are Sandra Torres and Alejandro Giammattei (BBC 2019) competing to replace President Morales, with many accusations about their checkered political past.1 The first round of voting took place on June 16, 2019 and results were conclusive by the 17th. The outcome of the election showed former first lady Sandra Torres of the National Unity of Hope party emerge as the leading candidate, scoring 25.7% of the vote followed by Alejandro Giammatei of the conservative party Vamos, who won 13.92% of the vote.2 The three following candidates obtained 11.2%, 10.5%, and 6.2%, respectively, and represent vastly different political agendas and backgrounds, ranging from establishment conservative to grassroots liberal.3 Since no candidate, however, garnered more than 50% of the vote during the first round, a second round of voting will take place on August 11.4 This election occurs at a critical moment for Guatemala, as the country finds itself facing many pressing domestic issues such as organized crime, poverty, and corruption,5 of which several candidates in the election are also accused, and challenges in foreign policy, most notably problematic relations with the United States. The stakes are high in this election as it would steer the general direction of Guatemala domestically and internationally. -

Chapter V Follow-Up of Recommendations Issued Report by the IACHR in Its Country Or Thematic Reports

2020 Chapter V Follow-up of recommendations issued report by the IACHR in its country or thematic reports Third report on follow-up on recommendations issued by the IACHR on the Situation of Human Rights in Guatemala Annual ANNUAL REPORT 2020 CHAPTER V FOLLOW-UP OF RECOMMENDATIONS ISSUED BY THE IACHR IN ITS COUNTRY OR THEMATIC REPORTS THIRD REPORT ON FOLLOW-UP ON RECOMMENDATIONS ISSUED BY THE IACHR ON THE SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN GUATEMALA* I. INTRODUCTION 1. The purpose of this Chapter is to follow-up on the recommendations issued in the report entitled "Situation of Human Rights in Guatemala" (hereinafter "Country Report"), 1 adopted on December 31, 2017 by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights ("the Commission," "the Inter-American Commission," or "the IACHR") pursuant to Article 59.9 of its Rules of Procedure. Under that provision, by means of Chapter V of its Annual Report, the Commission shall follow-up on measures adopted to comply with its recommendations issued in the country report. 2. Invited by the Republic of Guatemala ("Guatemala," "the State"), the IACHR paid an on-site visit to the country from July 31 to August 4, 2017. The IACHR drafted the Report on the Situation of Human Rights in Guatemala (Country Report), which was adopted by the IACHR on December 31, 2017. In the country report, the Commission pointed out that the information it had consistently received during its visit indicated that, in essence, more than 20 after the signing of the Peace Accords, several of the grounds that gave rise to the internal armed conflict persisted: the economy is still based on a concentration of economic power in the hands of a few, and a weak, poorly endowed, State structure due to scant tax revenue and high levels of corruption. -

Enlace De Archivo

Asociación de Investigación y Estudios Sociales GUATEMALA: MONOGRAFÍA DE LOS PARTIDOS POLÍTICOS 2004 – 2008 NIMD FUNDACIÓN KONRAD ADENAUER INSTITUTO HOLANDÉS PARA LA DEMOCRACIA MULTIPARTIDARIA 1 Asociación de Investigación y Estudios Sociales. Departamento de Investigaciones Sociopolíticas Guatemala: monografía de los partidos políticos 2004-2008 Guatemala, 2008 262p. 28cm 1. PARTIDOS POLÍTICOS.- 2. PARTICIPACIÓN POLÍTICA.- 3. FINANCIAMIENTO.- 4. ELECCIONES.- 5. VOTACIÓN.- 6. DIPUTADOS.- 7. ALCALDES.- 8. PARLAMENTO CENTROAMERICANO.- 9. AFILIACIÓN POLÍTICA.- 10. POLÍTICOS.- 11. GUATEMALA. ISBN: 99939-61-33-7 Asociación de Investigación y Estudios Sociales Departamento de Investigaciones Sociopolíticas (DISOP) GUATEMALA: Monografía de los partidos políticos 2004-2008 Coordinación general: Marco Antonio Barahona Equipo DISOP: Ligia Ixmucané Blanco Gabriela Carrera Karin Erbsen de Maldonado Carlos Escobar Armas Zaira Lainez Justo Pérez José Carlos Sanabria Carlos René Vega Fernández Apoyo técnico y administrativo: Amilza Orozco Silvia Rodas Ana María Specher Ciudad Guatemala, Centro América, septiembre de 2008 La elaboración de esta Monografía ha sido posible gracias al apoyo de: Fundación Konrad Adenauer de la República Federal de Alemania (KAS) y Fundación SOROS Guatemala Su publicación y presentación pública han sido posibles gracias al apoyo de: Fundación Konrad Adenauer de la República Federal de Alemania (KAS), Instituto Holandés para la Democracia Multipartidaria (nIMD) y Fundación Soros Guatemala 2 ASOCIACIÓN DE INVESTIGACIÓN Y ESTUDIOS -

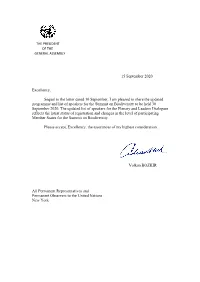

15 September 2020 Excellency, Sequel to the Letter Dated 10

THE PRESIDENT OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY 15 September 2020 Excellency, Sequel to the letter dated 10 September, I am pleased to share the updated programme and list of speakers for the Summit on Biodiversity to be held 30 September 2020. The updated list of speakers for the Plenary and Leaders Dialogues reflects the latest status of registration and changes in the level of participating Member States for the Summit on Biodiversity. Please accept, Excellency, the assurances of my highest consideration. Volkan BOZKIR All Permanent Representatives and Permanent Observers to the United Nations New York PROGRAMME SUMMIT ON BIODIVERSITY WEDNESDAY, 30 SEPTEMBER 2020 10.00 - OPENING SEGMENT 10.50 Opening and Welcome Remarks H.E. Mr. Volkan Bozkir President of the 75th session of the General Assembly Statement H.E. Mr. António Guterres Secretary-General, United Nations Statement H.E. Mr. Munir Akram President of Economic and Social Council Statement H.E. Mr. Abdel Fattah Al Sisi President of the Arab Republic of Egypt Host of the fourteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity Statement H.E. Mr. Xi Jinping President of the People's Republic of China Host of the fifteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity OPENING SEGMENT Fireside Chat • Moderator Mr. Achim Steiner, UNDP Administrator • Ms. Inger Andersen Executive Director, UN Environment Programme (UNEP) • Ms. Elizabeth Maruma Mrema Executive Secretary, Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) 1 • Ms. Ana María Hernández Salgar Chair, Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) Statement from Eminent Person HRH Prince Charles Prince of Wales Prince of Wales Conservation Trust Statement from Youth Representative Ms. -

El Informe De La Designación Por El Presidente Giammattei

Proceso de designación de magistrados de la Corte de Constitucionalidad 2021 – 2026 Presidente de la República en Consejo de Ministros Marzo, 2021 I. Presentación La Corte de Constitucionalidad es uno de los órganos de control jurídico más importantes de la era democrática del país. Su incorporación como tribunal permanente e independiente, en la Constitución Política de 1985, fue uno de los avances más importantes en materia de institucionalidad democrática. Su funcionamiento no ha estado exento de dificultades, ni de señalamientos, sin embargo, sus aportes en la defensa del orden constitucional han sido valiosos a lo largo de la historia. Una de las contribuciones más visibles fue su intervención para la restauración del orden constitucional en la época del autogolpe de Estado del presidente Jorge Serrano Elías. Los magistrados de la Corte de Constitucionalidad son designados o elegidos cada cinco años, por los entes facultados para ello por la Constitución Política y en la ley. El presidente de la República en Consejo de Ministros es uno de los cinco entes encargados de la designación de magistrados a la Corte de Constitucionalidad. Esa responsabilidad ha sido asumida con la entrada en vigor de la nueva Constitución Política de la República, desde el periodo presidencial de Vinicio Cerezo Arévalo (1986-1991). Ni la Constitución, ni la Ley de Amparo, Exhibición Personal y de Constitucionalidad, establecen un procedimiento preciso para la designación de magistrados por parte del presidente en Consejo de Ministros. No obstante, tanto los tratados internacionales en materia de derechos humanos como la misma Constitución promueven principios como la publicidad y el acceso a los actos de la administración pública, dos supuestos de gran relevancia para la transparencia.