Non-Normative” Characters in Musical Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boring Oregon & Dull Scotland a Pair for the Ages BORING COMMUNITY

Boring Oregon & Dull Scotland A Pair for the Ages BORING COMMUNITY PLANNING ORGANIZATION “A Forum for Communication and Discussion for a Vibrant Community” Home of the “North American Bigfoot Center” P. O. Box 363 Boring, Orygun 97009 Michael Fitz, Chair DAYTIME TELEPHONE: 503-502-5837 EMAIL: [email protected] www.boringcpo.org NOTICE OF PUBLIC MEETING 1 JUNE 2021 at 7:01 PM AT THE Boring Grange On SE Grange St MEETING AGENDA MEET AND GREET, AROUND 6:00 PM CHANGE TO THE MEETING: WE ARE STREAMING THE MEETING FROM OUR FACEBOOK PAGE. IF YOU HAVE QUESTIONS ON STREAMING PLEASE DIRECT THEM TO STEVE BATES, YOU WILL GET WAY BETTER ANSWERS THAN ASKING ME. 1. Meeting called to order, flag salute self introductions and a little trivia, statistics on what the average citizen knows, by source. 2. Reports and advisements: A. Boring Water District B. Boring Oregon Foundation C. Boring-Damascus Grange D. Mt. Hood Center (Old Boring Equestrian Center) Liz Delmatoff the Learning Collective education administrator will have answers to your questions on the full time equestrian learning center and how it relates to the school system, charter schools and home schooling. 4. A moment of Boring History presented by Bruce Haney Bruce’s new book is out, on sale in several places around the county and I have read it. Well written and a very enjoyable read, I don’t know what he will have tonight but I know that it is never a boring minute. 5. Minutes of the previous meeting. 6. Treasurers report. 7. Land use issues: A. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

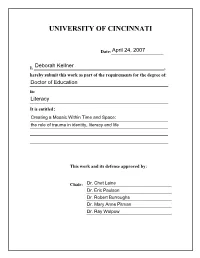

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Creating a Mosaic Within Time and Space: the role of trauma in identity, literacy, and life A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION In the Department of Literacy of the College of Education, Criminal Justice and Human Services Winter 2007 By DEBORAH KELLNER Committee Chair: Chet Laine, Ph.D. Abstract This dissertation presents a qualitative, ethnographic, life history study of the link between trauma exposure and literacy habits of one female college developmental student. It is an investigation of the correlation between trauma-related symptoms, identity, literacy habits, and performance in all aspects of life. Furthermore, it is an analysis of the relationship of coping with trauma exposure to coping with schooling. In terms of trauma, this single case presents multiple and repetitive exposure to trauma and suggests that traumatic experiences emerge as part of a victim’s identity. Victimization is so overwhelming that the individual describes herself in the trauma experience rather than in some other way. Her symptoms closely align with the symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and her trauma exposure results in massive chaos during her schooling years. In terms of literacy, this data suggests that this individual’s external literacy skills, her reading and writing, as well as her internal literacy skills, her interpretation of her world and her life, have a strong affiliation with trauma. -

Michael Arnold: All Right

Michael Arnold: All right. Welcome to episode three, Monday state of mind. My name is Michael Arnold. I am the director of alumni and recovery support services for the harmony foundation. On this episode, we are going to continue talking about the stories we tell ourselves. So if you're driving, you're just waking up. Maybe you're headed to the gym or out on that morning walk, or just getting your day going. You're going to want to make sure to have a pen and a piece of paper, or you're just going to have to put this episode on repeat because the guests that I have today, she's going to drop some serious knowledge bombs on the stories we tell ourselves. So do you guys want to know who this guest is? Her name is LauraBeth Burkhalter. LB. Do you want to tell everybody a little bit of, just give everybody a little bit of backstory about who you are, what you do? LB: Good morning guys. I'm LB. I am a person in recovery and I grew up in a little town called Natchez Mississippi. I'm currently the Director of. Community Engagement for Jade Recovery in Lakewood, Colorado. And I'm super stoked that Michael asked me to be on this podcast today because if there's one thing I know about it's stories and what I used to tell myself, Michael Arnold: Right. You know, that's, I was really excited to be able to start this podcast series out. -

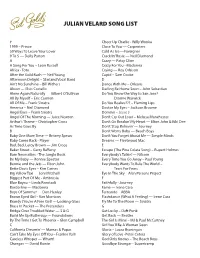

Julian Velard Song List

JULIAN VELARD SONG LIST # Cheer Up Charlie - Willy Wonka 1999 – Prince Close To You — Carpenters 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Cold As Ice —Foreigner 9 To 5 — Dolly Parton Cracklin’ Rosie — Neil Diamond A Crazy — Patsy Cline A Song For You – Leon Russell Crazy For You - Madonna Africa - Toto Crying — Roy Orbison After the Gold Rush — Neil Young Cupid – Sam Cooke Afternoon Delight – Starland Vocal Band D Ain’t No Sunshine – Bill Withers Dance With Me – Orleans Alison — Elvis Costello Darling Be Home Soon – John Sebastian Alone Again Naturally — Gilbert O’Sullivan Do You Know the Way to San Jose? — All By Myself – Eric Carmen Dionne Warwick All Of Me – Frank Sinatra Do You Realize??? – Flaming Lips America – Neil Diamond Doctor My Eyes – Jackson Browne Angel Eyes – Frank Sinatra Domino – Jesse J Angel Of The Morning — Juice Newton Don’t Cry Out Loud – Melissa Manchester Arthur’s Theme – Christopher Cross Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart — Elton John & Kiki Dee As Time Goes By Don’t Stop Believin’ — Journey B Don’t Worry Baby — Beach Boys Baby One More Time — Britney Spears Don’t You Forget About Me — Simple Minds Baby Come Back - Player Dreams — Fleetwood Mac Bad, Bad, Leroy Brown — Jim Croce E Baker Street – Gerry Raerty Escape (The Pina Colata Song) – Rupert Holmes Bare Necessities - The Jungle Book Everybody’s Talkin’ — Nilsson Be My Baby — Ronnie Spector Every Time You Go Away – Paul Young Bennie and the Jets — Elton John Everybody Wants To Rule The World – Bette Davis Eyes – Kim Carnes Tears For Fears Big Yellow Taxi — Joni Mitchell Eye In -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Real Stories of East LA L.A

Real Stories of East LA L.A. Poet Laureate Holding Out Winner of FRANCO AGUILAR LUIS J. RODRIGUEZ for Lady Luck by 6-Word-Story looks for ghosts on police brutality JOSEPH MATTSON contest in southern Mexico Real Stories of East LA Spring 2015 EAST LOS ANGELES COLLEGE Real Stories of East LA Spring 2015 Poetry Editors Gustavo Mateo, Nils Rabe Fiction Editors Joshua Inglada, Daniel Sosa Layout Board Alena Morales, Marcille Sanguino Business Manager Kevin Rocha Proofreader Extraordinaire Joshua Castro Staff Joanna Alvarado, Lucy Alvarez, Joshua Castro, Joshua Inglada, Gustavo Mateo, Alena Morales, Robert Perez, Nils Rabe, Kevin Rocha, Marcille Sanguino, Daniel Sosa Faculty Editor Dustin Lehren Concept Design Diana Chang Layout and Design Production Yegor Hovakimian Milestone Committee Joan Goldsmith Gurfield, Dolores Carlos, Alexis Solis, Susan Suntree Cover Art Front cover: Photograph Franco Aguilar, What Lies There (Hacienda Photo Essay) Back cover: Oil on printed photograph Franco Aguilar & Jesus Barrales, Out of the Smoke Inside cover: Digital Photograph Jemima Wyman, Sample from fabric archive Milestone is published annually by the East Los Angeles College English Department, 1301 Avenida Cesar Chavez, Monterey Park, California 91754. U.S. Submission Guidelines: The editors invite digital submissions of poetry, fiction/non-fiction, comics, essays of literary interest, art, and photography. Guidelines at milestone.submittable.com 2 Contents Introduction . 5 Acknowledgments . 7 Amarillas | Joseph Hernandez . 8 This, My Father Talk- | Andrew Liu . 13 From The Municipal Gardens | Andrew Liu . 14 Sea Layers | Joshua Inglada . 16 My Main Conflict | Michael Guerra . 17 a + d + d + i + n + g | Joshua Castro . 18 #collegestudentproblems | Raul Meza . -

Ending the Secrecy Part 1: I Survived This Thing

Living Bridges Project Transcript Ending the Secrecy - Ending the Secrecy Part 1: I Survived This Thing [Music] VOICEOVER: The following audio is part of the Living Bridges Project, an anonymous story-collecting project documenting responses to child sexual abuse. For more, please visit LivingBridgesProject.com. [Music] STORYTELLER: I think I’ll begin the story by thinking about the very first time that I even – that I realized that I was a survivor of child sexual abuse. It was – I was at community college and taking a psychology course and the conversation at the moment at that class was about suppressed memories. And we talked about what suppressed memories were and at one point the professor gave us a sheet – almost like a check-off sheet to say if you check off more than, I guess, five of these things then maybe you should go speak to a counselor or a therapist because it might be – you might be dealing with some repressed memories. And I remember looking at the sheet and marking almost all of them on the sheet and I was a little confused by that. I think the second part of the class was watching videos of families trying to deal with and address child sexual abuse after it happened within the family. So, in particular it was about a father who had abused the daughter and the family trying to stay together in spite of the abuse. At one point in the class I remember feeling completely overwhelmed and, now knowing – looking back now I know I was having an anxiety attack, but I didn’t know then. -

“Is It Me? Am I Losing My Mind?” Living with Intimate Male Partners

“Is It Me? Am I Losing My Mind?” Living with Intimate Male Partners Presenting With Subjective Narcissistic Behaviours and Attitudes by Sherry Lynn Saunders Lane A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF EDUCATION Department of Educational Administration, Foundations and Psychology University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2020 Sherry Lynn Saunders Lane Abstract Mainstream culture and the media are increasingly using the terminology 'narcissism' as socio- cultural parlance to describe selfish and self-centered behaviors and attitudes in social relationships. The purpose of this phenomenological research study is to describe the lived experience of women who are in intimate relationships with male partners whom they characterize as having narcissistic behaviors and attitudes. The research focus is motivated by client-centered therapeutic orientations that encourage counselors to 'be present with' clients, even when the experiences lack objective validation. Unstructured interviews were used to collect data from three adult females. The data was analyzed using the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis approach. The participants' stories indicated that their relationships have identifiable phases and characteristics. The participants experienced diminished well-being, compromised self-differentiation, and pervasive loss. Pervasive loss served as a wake-up call and motivated the activation of participants’ residual sense of self to leave the relationships. In conclusion, while the terminology used to describe the intimate male partners may lack validation, the women perceive that their experiences negatively affected their lives. The women also recognized and regretted their lack of capability to negotiate dignified positioning in their intimate relationships. -

Organ Recital Hall / University Center for the Arts

ORGAN RECITAL HALL / UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR THE ARTS ⊲ ⊲ ⊲ CO-PRESENTED BY THE LINCOLN CENTER AND COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY ⊳ ⊳ ⊳ RE-IMAGING SONDHEIM FROM THE PIANO APRIL 17, 7:30 P.M. TONIGHT’S PROGRAM ANTHONY DE MARE / LIAISONS: RE-IMAGINING SONDHEIM FROM THE PIANO (ALL WORKS BASED ON MATERIAL BY STEPHEN SONDHEIM) Into the Woods (2013) Andy Akiho (Into the Woods) The Ladies Who Lunch (2010) David Rakowski (Company) Color and Light (2012) Nico Muhly (Sunday in the Park with George) Finishing the Hat –Two Pianos (2010) Steve Reich (Sunday in the Park with George) I Think About You (2010) Paul Moravec (after “Losing My Mind” — Follies) That Old Piano Roll (2014) Wynton Marsalis (Follies) Johanna in Space (2014) Duncan Sheik (after “Johanna” – Sweeney Todd) The Demon Barber (2010) Kenji Bunch (A Fantasia on “The Ballad of Sweeney Todd”) No One Is Alone (2010) Fred Hersch (Into the Woods) I’m Excited. No You’re Not. (2010) Jake Heggie (after “A Weekend in the Country” – A Little Night Music) FROM THE ARTIST Like many of us, I have long held in highest esteem the work of Stephen Sondheim, whose fearless eclecticism has emboldened many a musical risk-taker. Over the years, I often found myself imagining how the familiar and beloved songs of the Sondheim canon would sound if transformed into piano works along the lines of what Art Tatum and Earl Wild did for George Gershwin and Cole Porter, or what Liszt did for Verdi, Schubert and so many others. In 2007, after many years of working with talented composers from across the musical spectrum, I decided to pursue a formal commissioning and concert project. -

Masculinities and College Men's Depression: Recursive Relationships

Copyright © eContent Management Pty Ltd. Health Sociology Review (2010) 19(4): 465–477. Masculinities and college men’s depression: Recursive relationships JOHN L OLIFFE School of Nursing, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada MARY T KELLY School of Nursing, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada JOY L JOHNSON School of Nursing, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada JOAN L BOTTORFF Faculty of Health and Social Development, University of British Columbia, Okanagan, BC, Canada ROSS E GRAY Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada JOHN S OGRODNICZUK Department of Psychiatry, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada PAUL M GALDAS School of Nursing, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada ABSTRACT Depression is a signifi cant problem among college men. This qualitative study examines the interplay between masculinities and depression among Canadian-based college men who self-identifi ed or were formally diagnosed with depression. The resulting three themes – mind matters, stalled intimacy and lethargic discontent – reveal the recursive relationships between masculinities and depression whereby depression quashed men’s aspirations for embodying masculine ideals, with depression potentially trig- gered by self-doubt and concerns about harbouring a faulty masculinity. Key fi ndings include par- ticipants’ juxtaposing their private negative self-talk with attempts to pass as self-assured in public; anxieties about neediness and vulnerability negating their -

An Epistolary: Losing My Mind September 04, 2017 Dear Cory

An Epistolary: Losing my Mind September 04, 2017 Dear Cory, Today marks a year since we last saw each other. Three hundred and sixty-five days. Wow. I thought I'd bring out my pen and notepad for a final letter, an irrevocable goodbye. I finally feel that I’ve grown throughout this journey and now I own the air around me, and in some way, I thank you for that. I’ve created new friendships, travelled around and had a few nights out. But, I feel so much happier and at last, I feel like I know who I am. It’s been one crazy and emotional journey, hasn’t it? Felt like a perennial rollercoaster, but I finally feel that it’s coming to a halt. Time to put us behind and look to the future. I hope that one day we can look back on this experience and be thankful for the emotions it has put us both through. I know that one thing I am grateful for is that your negative ways made me stronger, I am now a young woman that has a positive outlook on life. I hope you have realised your wrongs and are working on them. I hope you have grown to understand the feelings that I have felt. I hope that you have learnt to overcome your self-centered ways. I hope and wish you all the best in life. I hope you never have to go through what I have and I hope another girl does not have to go through it with you.