Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E X I L E and No St a L Gi a in Arabic and Hebrew Poetry in Al -Andal Us (Muslim Spain) Thesis Submitted F O R the Degree Of

Exile and Nostalgia in Arabic and Hebrew Poetry in al-Andalus (Muslim Spain) Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of London by Rafik M. Salem (B .A.; M.A., Cairo) School of Oriental and African Studies December, 1987 ProQuest Number: 10673008 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673008 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ( i ) ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to examine the notions of "exile" (ghurba) and "nostalgia" (al-banTn i 1a-a 1-Wafan) in Arabic and Hebrew poetry in al-Andalus (Muslim Spain). Although this theme has been examined individually in both Arabic and Hebrew literatures, to the best of my knowledge no detailed comparative analysis has previously been undertaken. Therefore, this study sets out to compare and contrast the two literatures and cultures arising out of their co-existence in al-Andalus in the middle ages. The main characteristics of the Arabic poetry of this period are to a large extent the product of the political and social upheavals that took place in al-Andalus. -

Contemporary Arab Women Writers' Reconfigurations of Home and Belonging Ghadir Khalil Zannoun University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2011 Postmodern Subjects and the Nation: Contemporary Arab Women Writers' Reconfigurations of Home and Belonging Ghadir Khalil Zannoun University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Modern Literature Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Zannoun, Ghadir Khalil, "Postmodern Subjects and the Nation: Contemporary Arab Women Writers' Reconfigurations of Home and Belonging" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 102. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/102 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. POSTMODERN SUBJECTS AND THE NATION: CONTEMPORARY ARAB WOMEN WRITERS’ RECONFIGURATIONS OF HOME AND BELONGING POSTMODERN SUBJECTS AND THE NATION: CONTEMPORARY ARAB WOMEN WRITERS’ RECONFIGURATIONS OF HOME AND BELONGING A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies By Ghadir Zannoun Birzeit University Bachelor of Arts in English Language and Literature, 1997 University of Arkansas Master of Fine Arts in Literary Translation, 2004 August 2011 University of Arkansas ABSTRACT A lot has been said about the declining status of -

Patrizia Onesta LAUZENGIER-Washl-INDEX

Patrizia Onesta LAUZENGIER-WASHl-INDEX, GARDADOR CUSTOS: The "Enemies of Love" in Proven~al, Arabo-Andalusian, and Latin Poetry Among the range of possible connections between Arabo-Andalusian lyric, which emerged on Iberian soil around the eighth century, and the rise of love poetry in Provencel at the end of the eleventh century, scholars have identified a motif which perhaps merits further reflec tion:2 that is, the so-called "enemies of love," characters that create numerous and diverse difficulties for the lovers and seek to block the realisation of their desires. The theme is a topos of the love poetry of every age, and thus it has played a secondary role in studies of the ori gins of troubadour poetry, including those studies that sought such ori gins on Spanish soil. However, even if a theme is present in a number of cultures, as in the present case, the reader may still distinguish closer relations between particular uses of it. This occurs when given charac teristics and constitutive elements of the theme demonstrate traits common to two cultures but not found in others, which are such as to al low the reader to detect a reciprocal influence between the two literary traditions or, indeed, the possible dependence of one tradition on the other, with specific regard to the theme in question. SCRIPTA MEDITERRANEA, Vols XIX-XX 1998-1999, 119 lThe substantive Provence and the adjective Provern;:al are used in this article in reference to the ancient Provincia of the Romans, and not to the region of modem France, which is much smaller than that territory where a courtly poetry emerged at the end of the eleventh century. -

In the Teaching Department of the University, Vide Paper Read (1) Above

File Ref.No.101610/GA - IV - B2/2019/Admn UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT Abstract General and Academic - Faculty of Language & Literature- Scheme and Syllabus of MA Arabic Language and Literature Programme as per CCSS PG Regulation 2019 incorporating Outcome Based Education- Implemented in the Teaching Department of the University w.e.f 2020 Admission onwards - Subject to ratification by Academic Council -Orders Issued. G & A - IV - B U.O.No. 5598/2021/Admn Dated, Calicut University.P.O, 26.05.2021 Read:-1. U.O.No. 15363/2019/Admn Dated 31.10.2019 2. Minutes of the meeting of the Board of Studies in Arabic PG held on 23/02/2021 (Item No 2) 3. Minutes of the meeting of the Faculty of Language and Literature dtd 25/03/2021 (item No 5) 4. orders of Vice Chancellor dated 27/04/2021 ORDER 1. The scheme and syllabus of MA Arabic Language and Literature Programme under CCSS PG Regulations 2019, w.e.f 2019 admission onwards has been implemented in the Teaching Department of the University, vide paper read (1) above. 2. The meeting of the Board of Studies in Arabic PG held on 23/02/2021 vide paper read as (2) above has resolved to approve outcome based syllabus of MA Arabic Language and Literature Programme, in accordance with CCSS PG Regulation 2019, with effect from 2020 Admn onwards. 3. The meeting of the Faculty of Language and Literature held on 25/03/2021, vide paper read (3) above, has approved the minutes of the meeting of the Board of Studies in Arabic PG held on 23/02/2021. -

Nature As a Motif in Arabic Andalusian Poetry and English Romanticism

Journal of Critical Studies in Language and Literature ISSN: 2732-4605 www.jcsll.gta.org.uk Nature as a Motif in Arabic Andalusian Poetry and English Romanticism Ghassan Aburqayeq University of California, Santa Barbara, USA Email: [email protected] Received: 27/04/2020 Accepted: 23/06/2020 Published: 01/07/2020 Volume: 1 Issue: 2 How to cite this paper: Abutqayeq, Gh. (2020). Nature as a Motif in Arabic Andalusian Poetry and English Romanticism. Journal of Critical Studies in Language and Literature, 1(2), 52- 61 DOI: https://doi.org/10.46809/jcsll.v1i2.61 URL: https://jcsll.gta.org.uk/index.php/JCSLL/article/view/61/39 Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and Global Talent Academy Ltd. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract This paper examines some tenets in the Andalusian and Romantic poetry and shows how poets such as Ibrahim Ibn Khafāja (1058-1138) and William Wordsworth (1770 –1850) used nature as a motif in their poetry. Relying on a historical approach, this paper links smaller features such as themes and literary devices in the Andalusian and Romantic poetry with larger features, including genre, traditions, and cultural system. I argue that the emphasis on both the larger and smaller features of poetry creates what Franco Moretti calls “distant reading.” Comparing and contrasting Ibn Khafāja’s “the Mountain” and Wordsworth’s “the Daffodils,” for instance, introduces nature as a recurrent theme in both Andalusian and Romantic literary traditions, reinforcing Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s description of poetry as a common possession of humanity” (Goethe 229). -

Curriculum Vitae MICHAEL a SELLS 08 December 2015

Michael Sells CV 08 December 2015 1 Curriculum Vitae MICHAEL A SELLS 08 December 2015 John Henry Barrows Professor of the History and Literature of Islam Professor of Comparative Literature University of Chicago Divinity School, Swift Hall 1025 E. 58th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 [email protected] EDUCATION The University of Chicago . 1978–1982 . Ph.D. 1982 Center for Arabic Studies Abroad, Cairo, Egypt . 1977–1978 The University of Chicago . 1976–1977 . M.A. 1977 Gonzaga University. 1967–1971 . A.B. 1971 (Florence Italy Program, 69–70) POSITIONS HELD 7/05 – University of Chicago, John Henry Barrow Professor of the History and Literature of Islam, Divinity School; and since 2009, Professor of Comparative Literature at the University of Chicago. 5/95–7/05 Haverford College, Professor of Religion and Emily Judson Baugh and John Marshall Gest Professor of Comparative Religions. (7/97–7/98 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship, in residence) 7/92–6/96 Haverford College, Chairperson, Dept. of Religion. 5/90–5/95 Haverford College, Associate Professor, Department of Religion. 8/84–5/90 Haverford College, Assistant Professor, Department of Religion 8/82–8/84 Stanford University, Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow. 8/72–6/74 Peace Corps, Tunisia. Lycée de Medenine. Lycée de Foum Tatahouine. HONORS 2004 Choice "Academic Book of the Year" Award for The New Crusades: Constructing the Muslim Enemy (Columbia University Press, 2004). 2003 Andrew Mellon New Directions Fellowship: for Work on Religion and Conflict in Bosnia- Hercegovina. 2002 Annual Selection of Approaching the Qur'an for the Required Book of the Year, University of North Carolina Summer Reading Program. -

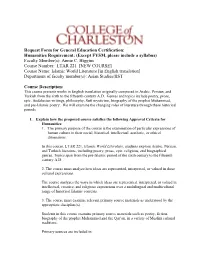

Request Form for General Education Certification: Humanities Requirement: (Except FYSM, Please Include a Syllabus) Faculty Member(S): Annie C

Request Form for General Education Certification: Humanities Requirement: (Except FYSM, please include a syllabus) Faculty Member(s): Annie C. Higgins Course Number: LTAR 221 [NEW COURSE] Course Name: Islamic World Literature [in English translation] Department of faculty member(s): Asian Studies/IIST Course Description: This course presents works in English translation originally composed in Arabic, Persian, and Turkish from the sixth to the fifteenth century A.D. Genres and topics include poetry, prose, epic, Andalusian writings, philosophy, Sufi mysticism, biography of the prophet Muhammad, and pre-Islamic poetry. We will examine the changing roles of literature through these historical periods. I. Explain how the proposed course satisfies the following Approval Criteria for Humanities: 1. The primary purpose of the course is the examination of particular expressions of human culture in their social, historical, intellectual, aesthetic, or ethical dimensions. In this course, LTAR 221, Islamic World Literature, students explore Arabic, Persian, and Turkish literature, including poetry, prose, epic, religious, and biographical genres. Topics span from the pre-Islamic period of the sixth century to the fifteenth century A.D. 2. The course must analyze how ideas are represented, interpreted, or valued in these cultural expressions. The course analyzes the ways in which ideas are represented, interpreted, or valued in intellectual, creative, and religious expressions over a multilingual and multicultural range of historical Islamic contexts. 3. The course must examine relevant primary source materials as understood by the appropriate discipline(s). Students in this course examine primary source materials such as poetry, fiction, biography of the prophet Muhammad,and the Qur’an, in a variety of Muslim cultural traditions. -

Undergraduate Guide Academic Year - 2016/2017

UNDERGRADUATE GUIDE ACADEMIC YEAR - 2016/2017 Faculty of Islamic Studies and Arabic Language South Eastern University of Sri Lanka Oluvil # 32360 Sri Lanka http://www.seu.ac.lk/fia Published by: Faculty of Islamic Studies and Arabic Language South Eastern University of Sri Lanka Oluvil# 32360 Sri Lanka February 2018 The Faculty of Islamic Studies and Arabic Language reserves itself the right to change any information given herein as it considers appropriate, without prior notice. I South Eastern University of Sri Lanka VISION MISSION To be an Internationally Renowned Center in To Provide Expanded Opportunities for Higher South Asia for Higher Learning and Innovations in Learning of International Standards through Sciences, Technologies and Humanities Generation and Dissemination of Knowledge and Innovations Focused on Regional and National Needs, Social Harmony and Stakeholders' Empowerment and Satisfaction. II Faculty of Islamic Studies and Arabic Language VISION MISSION To be an internationally renowned centre for To be an internationally renowned centre for excellence in Islamic and Arabic Studies. integrating Islamic and Arabic studies in to relevant discipline to produce employable graduates, improve the quality and innovation in teaching, learning and research satisfying the stakeholders while contributing to society, region and nation. III Our Graduate Profile In accordance to the established trend and international norms in higher education, it is necessary to identify and make use of learning outcomes in higher education, FIA approached mapping out its graduate profile through the discussion with staff, students, graduates, alumni and other stakeholders, more particularly the selected community representatives. This graduate profile that FIA seeks to engender in graduates of its study programs is set based on the intended learning outcomes that describe the attributes which will prepare them for future employment, further study and for good citizenship. -

Appendix of Translated Poetry

APPENDIX OF TRANSLATED POETRY 1. Abu Dulaf و! آن ! اا ر ة ا***و ا أودى أآ ا و2ه.ت أ)0/ وأا( ! ا.ه *** ا, +ى ($ )' ا&!ك وا$# + ا+س آ; ا+ س ا/ و ا/*** أ89( 70 ا56 ! ا3 إ' !3 إ' F+G ،; آ; أرض C +9ي *** إذا @ق + ># (7ل )+= إ' ># + ا.( O ! ا&Nم واL$ ***+3#ف )' اJ و(HI . اH 2. Al-Ghazal >ل وR( !ج آF/ل *** وHC+ رح ! در و 2ل T2, اT وا(/H, )ى SC ا/ل *** وS! '#C ات إ+ ) ل أ, ات رأي ا . ل *** L U Tم + رT رأس !ل 3. Abu al-ʿ Arab ا/وم FCي ا$ = *** إ )' Wر وا/ ب 4. Abu Firas A. “A Captive’s Suffering” َ َ ً إِ [ن ا ِ 3َ/ّ*** َد ُ!ُ= َاRَ .f6^` هَُ اومِ !UTٌُ*** وََ=ُ اIمِ >َُ^ َ َ!Fِ Hُ.ّاً U 3ُدِف***)َِ@ً !ِ[ ُ ِ ^` B. “Separation” T. آ+, أL2 ا/. !+S و*** Nد إذا !Oّ< ,a2 ا9. bL و ++ !S >3 ٌ*** و أ!; ا+$س وو). C. “The Byzantines Are Coming!” هe8 اFش N ) cFCدآ$!***U L$ وا3ّ/ن / أآ ! UO9 ّ ;$C***وا/ 2ّ !3^ ا&(ن 178 THE [EUROPEAN] OTHER ا +ن CN+ا أ!آgO+***U اا( اا( hW/ . اi إن hC/ا***e3) OHI U $ن D. Selected lines from the hijaʾ of Nicephorus Phocas أU6@ U(7C اد. أ(+ *** و( أد اب (ف ا أC).( ب H' آj(+ *** وإك O ^3 U >/+ )3/ H0 .T+ اب ! >/; هO +L *** e8 أ.ا وآ+, O آ/ N<j!+ أFت أم + *** وأ. -

AIGUADOLÇ 35.Indd

UNA GENEALOGIA POÈTICA I CULTURAL (LA POESIA ANDALUSINA EN L’OBRA DE JOSEP PIERA) Jaume Pont ES PETJADES DE LA TRADICIÓ POÈTICA ÀRAB, I MOLT especialment la importància que el llegat cultural i líric d’Al-Àn- dalus ha tingut en l’obra del valencià Josep Piera, es remunten a un dels llibres de poemes primerencs que l’autor va escriure en castellà, Qasida (1972). Vuit anys més tard reafi rmaria el seu interés, ara fundacionalment en català, tot publicant les versions de quatre poetes de l’Orient d’Al-Àndalus dins El somriure de l’herba (1980). Entre els dos llibres de poemes citats s’havia produït, però, un canvi substancial: un canvi que afectava la interioritza- ció mateixa dels referents poètics en un fet de llengua, de to i d’estil. En l’escriptura poètica d’El somriure de l’herba, Piera donava pas a un procés d’assimilació de la tradició lírica àrab que el duia a personalitzar aquesta tradició, a transformar-la i singularitzar-la en uns trets poeticoculturals defi nitivament propis. Això ho va veure molt bé Eduard J. Verger (1991: 15) en l’excel·lent pròleg que va posar a Dictats d’amors. (Poesia 1971- 1991), de Josep Piera, quan escrivia: L’evocació del món àrab havia pres ja en El somriure de l’herba una signifi cació diferent de la que havia tingut en la Qasida: de ser la fastuosa antiguitat on l’autor projectava el record de la pròpia passió amorosa, fent-lo així més remot però també més dòcil a la possessió del somieig, dotant-lo d’una “realitat” intemporal i fabulosa en l’afany de tornar-lo immarcescible, aquell món havia passat a ser, en l’esplendor de les seves ramifi cacions locals, una de les fonts del passat col·lectiu encara suscep- tibles de reapropiació i actualització com a senya d’identitat, un temps mític on localitzar uns orígens sustentadors: com ho era la infantesa, 45 amb els seus jocs i les seues cançons, en el pla individual. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Literacy, Munificence and Legitimation of Power during the Reign of the Party Kings in Muslim Spain Schippers, A. Publication date 1996 Document Version Final published version Published in Tradition and Modernity in Arabic Language and Literature Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Schippers, A. (1996). Literacy, Munificence and Legitimation of Power during the Reign of the Party Kings in Muslim Spain. In J. R. Smart (Ed.), Tradition and Modernity in Arabic Language and Literature (pp. 75-86). Curzon. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:05 Oct 2021 Tradition and Modernity in Arabic Language and Literature and turn their backs on her in adversity! Glory to us who make a stand. -

Convenzione E Originalità Nella Poesia Di Al-Andalus

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Convenzione e originalità nella poesia di al-Andalus Schippers, A. Publication date 1999 Document Version Final published version Published in Quaderni di Studi Arabi Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Schippers, A. (1999). Convenzione e originalità nella poesia di al-Andalus. Quaderni di Studi Arabi, 17, 53-70. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:01 Oct 2021 ARIE SCHIPPERS CONVENZiONE E ORIGINALITA NELLA POESIA DI AL-ANDALUS* Si ritiene che la letteralura araba andaliisa si sia direttamente ispirata a quella araba orienlale, o piu precisamente ciie la letteralura araba andalusa sia una continuazione e una ripresa dei temi e dei inotivi dominanti ad Oriente. 1 poeti di al-Andalus cercavano di competerc con i modelli orientali.