Genes and Men

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rnai in Primary Cells and Difficult-To-Transfect Cell Lines

Automated High Throughput Nucleofection® RNAi in Primary Cells and Difficult-to-Transfect Cell Lines Claudia Merz, Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany; Andreas Schroers, amaxa AG, Cologne, Germany; Eric Willimann, Tecan AG, Männedorf, Switzerland. Introduction Materials & Methods - Workflow Using primary cells for RNAi based applications such as target identification or – validation, requires a highly efficient transfection displaying the essential steps of the automated Nucleofector® Process: technology in combination with a reliable and robust automation system. To accomplish these requirements we integrated the amaxa 1. Transfer of the cells to the Nucleocuvette™ plate, 96-well Shuttle® in a Tecan Freedom EVO® cell transfection workstation which is based on Tecan’s Freedom EVO® liquid handling 2. Addition of the siRNA, (Steps 1 and 2 could be exchanged), platform and include all the necessary components and features for unattended cell transfection. 3. Nucleofection® process, 4. Addition of medium, Count Cells 5. Transfer of transfected cells to cell culture plate for incubation ® Nucleofector Technology prior to analysis. Remove Medium The 96-well Shuttle® combines high-throughput compatibility with the Nucleofector® Technology, which is a non-viral transfection method ideally suited for primary cells and hard-to-transfect cell lines based on a combination of buffers and electrical parameters. Nucleocuvette Plate Add Nucleofector +– The basic principle and benefits of the (empty) Solution Cell of interest Gene of interest Nucleofector® -

Como Citar Este Artigo Número Completo Mais Informações Do

Encontros Bibli: revista eletrônica de biblioteconomia e ciência da informação ISSN: 1518-2924 Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciência da Informação - Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina STANFORD, Jailiny Fernanda Silva; SILVA, Fábio Mascarenhas e Prêmio Nobel como fator de influência nas citações dos pesquisadores: uma análise dos laureados de Química e Física (2005 - 2015) Encontros Bibli: revista eletrônica de biblioteconomia e ciência da informação, vol. 26, e73786, 2021, Janeiro-Abril Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciência da Informação - Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina DOI: https://doi.org/10.5007/1518-2924.2021.e73786 Disponível em: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=14768130002 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Redalyc Mais informações do artigo Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina e do Caribe, Espanha e Portugal Site da revista em redalyc.org Sem fins lucrativos acadêmica projeto, desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa acesso aberto Artigo Original Prêmio Nobel como fator de influência nas citações dos pesquisadores: uma análise dos laureados de Química e Física (2005 - 2015) Nobel Prize as an influencing factor in researchers' citations: an analysis of Chemistry and Physics laureates (2005 to 2015) Jailiny Fernanda Silva STANFORD Mestre em Ciência da Informação (PPGCI/UFPE) Bibliotecária-chefe Seminário Teológico Batista do Norte do Brasil (STBNB), Recife, Brasil [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2112-6561 Fábio Mascarenhas e SILVA Doutor em Ciência da Informação (USP), Professor Associado Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Departamento de Ciência da Informação, Recife, Brasil [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5566-5120 A lista completa com informações dos autores está no final do artigo RESUMO Objetivo: Analisa a influência nos índices de citação por parte dos pesquisadores que foram contemplados pelo prêmio Nobel nas áreas da Física e Química no período de 2005 a 2015. -

Widespread Gene Transfection Into the Central Nervous System of Primates

Gene Therapy (2000) 7, 759–763 2000 Macmillan Publishers Ltd All rights reserved 0969-7128/00 $15.00 www.nature.com/gt NONVIRAL TRANSFER TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH ARTICLE Widespread gene transfection into the central nervous system of primates Y Hagihara1, Y Saitoh1, Y Kaneda2, E Kohmura1 and T Yoshimine1 1Department of Neurosurgery and 2Division of Gene Therapy Science, Department of Molecular Therapeutics, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, 2-2 Yamadaoka, Suita, Osaka 565-0871, Japan We attempted in vivo gene transfection into the central ner- The lacZ gene was highly expressed in the medial temporal vous system (CNS) of non-human primates using the hem- lobe, brainstem, Purkinje cells of cerebellar vermis and agglutinating virus of Japan (HVJ)-AVE liposome, a newly upper cervical cord (29.0 to 59.4% of neurons). Intrastriatal constructed anionic type liposome with a lipid composition injection of an HVJ-AVE liposome–lacZ complex made a similar to that of HIV envelopes and coated by the fusogenic focal transfection around the injection sites up to 15 mm. We envelope proteins of inactivated HVJ. HVJ-AVE liposomes conclude that the infusion of HVJ-AVE liposomes into the containing the lacZ gene were applied intrathecally through cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) space is applicable for widespread the cisterna magna of Japanese macaques. Widespread gene delivery into the CNS of large animals. Gene Therapy transgene expression was observed mainly in the neurons. (2000) 7, 759–763. Keywords: central nervous system; primates; gene therapy; HVJ liposome Introduction ever, its efficiency has not been satisfactory in vivo. Recently HVJ-AVE liposome, a new anionic-type lipo- Despite the promising results in experimental animals, some with the envelope that mimics the human immuno- gene therapy has, so far, not been successful in clinical deficiency virus (HIV), has been developed.13 Based upon 1 situations. -

Phage Integration and Chromosome Structure. a Personal History

ANRV329-GE41-01 ARI 2 November 2007 12:22 by Annual Reviews on 12/13/07. For personal use only. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2007.41:1-11. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org ANRV329-GE41-01 ARI 2 November 2007 12:22 Phage Integration and Chromosome Structure. A Personal History Allan Campbell Department of Biological Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305-5020; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Genet. 2007. 41:1–11 Key Words First published online as a Review in Advance on lysogeny, transduction, conditional lethals, deletion mapping April 27, 2007 Abstract by Annual Reviews on 12/13/07. For personal use only. The Annual Review of Genetics is online at http://genet.annualreviews.org In 1962, I proposed a model for integration of λ prophage into the This article’s doi: bacterial chromosome. The model postulated two steps (i ) circular- 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130240 ization of the linear DNA molecule that had been injected into the Annu. Rev. Genet. 2007.41:1-11. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org Copyright c 2007 by Annual Reviews. cell from the phage particle; (ii ) reciprocal recombination between All rights reserved phage and bacterial DNA at specific sites on both partners. This 0066-4197/07/1201-0001$20.00 resulted in a cyclic permutation of gene order going from phage to prophage. This contrasted with integration models current at the time, which postulated that the prophage was not inserted into the continuity of the chromosome but rather laterally attached or synapsed with it. This chapter summarizes some of the steps leading up to the model including especially the genetic characterization of specialized transducing phages (λgal ) by recombinational rescue of conditionally lethal mutations. -

Biochemistrystanford00kornrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Program in the History of the Biosciences and Biotechnology Arthur Kornberg, M.D. BIOCHEMISTRY AT STANFORD, BIOTECHNOLOGY AT DNAX With an Introduction by Joshua Lederberg Interviews Conducted by Sally Smith Hughes, Ph.D. in 1997 Copyright 1998 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Arthur Kornberg, M.D., dated June 18, 1997. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Warburg Effect(S)—A Biographical Sketch of Otto Warburg and His Impacts on Tumor Metabolism Angela M

Otto Cancer & Metabolism (2016) 4:5 DOI 10.1186/s40170-016-0145-9 REVIEW Open Access Warburg effect(s)—a biographical sketch of Otto Warburg and his impacts on tumor metabolism Angela M. Otto Abstract Virtually everyone working in cancer research is familiar with the “Warburg effect”, i.e., anaerobic glycolysis in the presence of oxygen in tumor cells. However, few people nowadays are aware of what lead Otto Warburg to the discovery of this observation and how his other scientific contributions are seminal to our present knowledge of metabolic and energetic processes in cells. Since science is a human endeavor, and a scientist is imbedded in a network of social and academic contacts, it is worth taking a glimpse into the biography of Otto Warburg to illustrate some of these influences and the historical landmarks in his life. His creative and innovative thinking and his experimental virtuosity set the framework for his scientific achievements, which were pioneering not only for cancer research. Here, I shall allude to the prestigious family background in imperial Germany; his relationships to Einstein, Meyerhof, Krebs, and other Nobel and notable scientists; his innovative technical developments and their applications in the advancement of biomedical sciences, including the manometer, tissue slicing, and cell cultivation. The latter were experimental prerequisites for the first metabolic measurements with tumor cells in the 1920s. In the 1930s–1940s, he improved spectrophotometry for chemical analysis and developed the optical tests for measuring activities of glycolytic enzymes. Warburg’s reputation brought him invitations to the USA and contacts with the Rockefeller Foundation; he received the Nobel Prize in 1931. -

Sol Spiegelman, a Pioneer in Molecular Biology

They Wand 0SS tk Slmsldera of Giants: Sol S@egelman, a Piomer in l$lokcular Biology Number 21 May 23,1983 Science in our century has been Indeed, it is upon his widely acclaimed marked by tremendous upheavals in un- discoveries that much of the framework derstanding, brought about by momen- of the discipline now rests. Sol was still tous discoveries and extraordinary pe~ deeply involved in a number of projects ple. One such upheaval has occurred in when, tragically, he died following a biology. It began in the 1930s, when a brief illness on January 21, 1983.2 This new field, molecular biology, was born essay is dedicated to his memory, and to of the synthesis of five distinct disci- the surviving members of his family: hw plines: physical chemistry, crystallogra- wife, Helen; his daughter, Marjorie; and phy, genetics, microbiology, and bio- hk sons, Willard and George. chemistry.1 I deeply regret that Sol did not have Molecular biologists try to explain the opportunity to read this long biological phenomena at the molecular overdue discussion of his work. I had level. By the mid-twentieth century, planned to do this as part of our series of they had settled several problems that essays on various awards in science—in plagued previous generations of biolo- particular, the Feltnnelfi prize, men- gists. For instance, proteins and nucleic tioned later. Sol was one of the true acids had been known since the nine- giants of modem science. So it is with a teenth century to be very large mole- mixed sense of pain and gratitude that I cules, each consisting of long chains of use thk opportunity to pay tribute to a subunits—amino acids in the case of man whose genius was unique. -

Ontology-Based Methods for Analyzing Life Science Data

Habilitation a` Diriger des Recherches pr´esent´ee par Olivier Dameron Ontology-based methods for analyzing life science data Soutenue publiquement le 11 janvier 2016 devant le jury compos´ede Anita Burgun Professeur, Universit´eRen´eDescartes Paris Examinatrice Marie-Dominique Devignes Charg´eede recherches CNRS, LORIA Nancy Examinatrice Michel Dumontier Associate professor, Stanford University USA Rapporteur Christine Froidevaux Professeur, Universit´eParis Sud Rapporteure Fabien Gandon Directeur de recherches, Inria Sophia-Antipolis Rapporteur Anne Siegel Directrice de recherches CNRS, IRISA Rennes Examinatrice Alexandre Termier Professeur, Universit´ede Rennes 1 Examinateur 2 Contents 1 Introduction 9 1.1 Context ......................................... 10 1.2 Challenges . 11 1.3 Summary of the contributions . 14 1.4 Organization of the manuscript . 18 2 Reasoning based on hierarchies 21 2.1 Principle......................................... 21 2.1.1 RDF for describing data . 21 2.1.2 RDFS for describing types . 24 2.1.3 RDFS entailments . 26 2.1.4 Typical uses of RDFS entailments in life science . 26 2.1.5 Synthesis . 30 2.2 Case study: integrating diseases and pathways . 31 2.2.1 Context . 31 2.2.2 Objective . 32 2.2.3 Linking pathways and diseases using GO, KO and SNOMED-CT . 32 2.2.4 Querying associated diseases and pathways . 33 2.3 Methodology: Web services composition . 39 2.3.1 Context . 39 2.3.2 Objective . 40 2.3.3 Semantic compatibility of services parameters . 40 2.3.4 Algorithm for pairing services parameters . 40 2.4 Application: ontology-based query expansion with GO2PUB . 43 2.4.1 Context . 43 2.4.2 Objective . -

Running with (CRISPR) Scissors: Tool Adoption and Team Assembly

Running with (CRISPR) Scissors: Tool Adoption and Team Assembly Samantha Zyontz* MIT Sloan School of Management May 2019 Abstract Research tools are essential inputs to technological progress. Yet many new tools require specialized complementary know-how to be applied effectively. Teams in any research domain face the tradeoff of either acquiring this know-how themselves or working with external tool specialists, individuals with tool know-how independent of a domain. These specialists are scarce early on and can choose domain teams to create many applications for the tool or to focus on complicated problems. Ex ante it is unclear where the match between domain teams and external tool specialists dominates. The introduction of the DNA-editing tool CRISPR enables identification of external tool specialists on research teams by exploiting natural difficulties of applying CRISPR across disease domains. Teams have a higher share of external tool specialists in difficult diseases, especially for subsequent innovations. This suggests that external tool specialists and domain teams match more often to solve complex but influential problems. As more tools like Artificial Intelligence emerge, research teams will have to also weigh the importance of their possible solutions when considering how best to attract and collaborate with external tool specialists. * Ph.D. Candidate, MIT Sloan School of Management, Technological Innovation, Entrepreneurship, and Strategic Management. I am indebted to Scott Stern, Pierre Azoulay, Jeff Furman, Florenta Teodoridis, Michael Bikard, Danielle Li, and Tim Simcoe for their guidance and suggestions that immensely improved this paper. Appreciation also belongs to Joanne Kamens and her staff at Addgene, Aditya Kunjapur, Wes Greenblatt, and other CRISPR scientists for helping me to understand the science and institutions in this setting. -

Helke Rausch

THEODOR-HEUSS-KOLLOQUIUM 2017 Liberalismus und Nationalsozialismus – eine Beziehungsgeschichte Helke Rausch Liberalismus und Nationalsozialismus bei Ernst Jäckh – liberaler Phoenix, Grenzgänger und atlantischer „Zivil-Apostel“ Momentaufnahme einer inszenierten Beziehungsgeschichte: Jäckh und Hitler in Berlin, April 1933 In seiner Eigenschaft als langjähriger Leiter der Deutschen Hochschule für Politik in Berlin 1920 bis 1933 kam Ernst Jäckh 1933 zu seinem unmittelbarsten Direktkontakt mit dem neu- en Regime und seinem „Führer“. Jäckh stand unter akutem Handlungsdruck, sich gegenüber den neuen Machthabern zu positionieren. Während er in seinen Memoiren und andernorts ein hagiographisches Bild von seiner eigenen Überlegenheit und Widerständigkeit im Um- gang mit Hitler zeichnete, demzufolge er phoenixgleich als standhaft liberaler Regimegegner dem Diktator entgegentrat,1 konnte er trotz dieser auf den Erhalt der Hochschule zielenden Unterredung seine Institution nicht halten. Wie auch immer Jäckhs Beziehungsstrategie ge- genüber dem NS Anfang 1933 ausgesehen haben mag, sein Kalkül schlug gründlich fehl. Er musste das übergriffige Regime gewähren lassen. Die offizielle Gleichschaltung der Hoch- schule zog sich zwar noch bis 1937 hin, bevor das Institut als Reichsanstalt firmieren und schließlich 1940 den „Auslandswissenschaften“ als dezidierten NS-Politikwissenschaften zu- geordnet werden sollte. 2 Schon zuvor aber löste Jäckh den Verein Deutsche Hochschule für Politik e.V. Ende April 1933 auf.3 These und Argument Die Symptomatik des Direktkontakts zwischen dem Liberalen Jäckh und der NS-Führung be- steht nicht so sehr in einem vordergründigen Lackmustest für Jäckhs liberalen Widerstands- 1 Jäckh tischte nach verschiedenen Seiten hin eine ominöse Widerstandsgeschichte auf. Die Sebstheroisierung in seinen Memoiren kippt fast zur Farce, vgl. etwa Ernst Jäckh: Weltsaat. Erlebtes und Erstrebtes, Stuttgart 1960, S. -

Mautner, Karl.Toc.Pdf

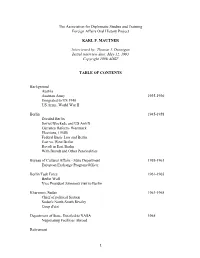

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project KARL F. MAUTNER Interviewed by: Thomas J. Dunnigan Initial interview date: May 12, 1993 opyright 1998 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Austria Austrian Army 1 35-1 36 Emigrated to US 1 40 US Army, World War II Berlin 1 45-1 5, Divided Berlin Soviet Blockade and US Airlift .urrency Reform- Westmark Elections, 01 4,1 Federal Basic 2a3 and Berlin East vs. West Berlin Revolt in East Berlin With Brandt and Other Personalities Bureau of .ultural Affairs - State Department 1 5,-1 61 European E5change Program Officer Berlin Task Force 1 61-1 65 Berlin Wall 6ice President 7ohnson8s visit to Berlin 9hartoum, Sudan 1 63-1 65 .hief of political Section Sudan8s North-South Rivalry .oup d8etat Department of State, Detailed to NASA 1 65 Negotiating Facilities Abroad Retirement 1 General .omments of .areer INTERVIEW %: Karl, my first (uestion to you is, give me your background. I understand that you were born in Austria and that you were engaged in what I would call political work from your early days and that you were active in opposition to the Na,is. ould you tell us something about that- MAUTNER: Well, that is an oversimplification. I 3as born on the 1st of February 1 15 in 6ienna and 3orked there, 3ent to school there, 3as a very poor student, and joined the Austrian army in 1 35 for a year. In 1 36 I got a job as accountant in a printing firm. I certainly couldn8t call myself an active opposition participant after the Anschluss. -

The Making of a Biochemist

book reviews disappearance of kuru as an important In the late 1920s, he looked into the effect TION episode in our understanding of the risks of light on the inhibition by carbon monox- A associated with this type of infectious ide of respiration in living cells. This work process. Informing the wider community of encompassed considerations of photo- these risks may lead to a more helpful debate chemical processes in terms of quantum about the public health policies required chemistry, and the use of the manometer, NOBEL FOUND to minimize the chances of another BSE photoelectric cell and spectroscope. From epidemic. Books such as this are useful in the shape of the curve obtained by plotting this context. the effectiveness of light against its wave- Colin L. Masters is in the Department of Pathology, length, it was possible to deduce the resem- 8 The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, blance between the respiratory ferment and 3052, Australia. haemins. Warburg was awarded the Nobel prize for physiology or medicine in 1931 for his recognition of the haemin-type nature of the respiratory ferment and its underlying The making principles. The development of Warburg’s theoreti- of a biochemist cal thinking and experimental procedures are Otto Warburgs Beitrag zur ably chronicled in Petra Werner’s introducto- Atmungstheorie: Das Problem der ry essay. Her book is the first volume of an Sauerstoffaktivierung* edition of Warburg’s correspondence Brilliant but flawed: Warburg tended to pettiness. by Petra Werner deposited in the Berlin–Brandenburg Aca- Basilisken-Presse: 1996. Pp. 390. DM136 demy of Sciences. Regrettably, the 143 pub- 1950).