673 Phylogeny of the Decapoda Reptantia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Classification of Living and Fossil Genera of Decapod Crustaceans

RAFFLES BULLETIN OF ZOOLOGY 2009 Supplement No. 21: 1–109 Date of Publication: 15 Sep.2009 © National University of Singapore A CLASSIFICATION OF LIVING AND FOSSIL GENERA OF DECAPOD CRUSTACEANS Sammy De Grave1, N. Dean Pentcheff 2, Shane T. Ahyong3, Tin-Yam Chan4, Keith A. Crandall5, Peter C. Dworschak6, Darryl L. Felder7, Rodney M. Feldmann8, Charles H. J. M. Fransen9, Laura Y. D. Goulding1, Rafael Lemaitre10, Martyn E. Y. Low11, Joel W. Martin2, Peter K. L. Ng11, Carrie E. Schweitzer12, S. H. Tan11, Dale Tshudy13, Regina Wetzer2 1Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PW, United Kingdom [email protected] [email protected] 2Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90007 United States of America [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3Marine Biodiversity and Biosecurity, NIWA, Private Bag 14901, Kilbirnie Wellington, New Zealand [email protected] 4Institute of Marine Biology, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung 20224, Taiwan, Republic of China [email protected] 5Department of Biology and Monte L. Bean Life Science Museum, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602 United States of America [email protected] 6Dritte Zoologische Abteilung, Naturhistorisches Museum, Wien, Austria [email protected] 7Department of Biology, University of Louisiana, Lafayette, LA 70504 United States of America [email protected] 8Department of Geology, Kent State University, Kent, OH 44242 United States of America [email protected] 9Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum, P. O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands [email protected] 10Invertebrate Zoology, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, 10th and Constitution Avenue, Washington, DC 20560 United States of America [email protected] 11Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, Science Drive 4, Singapore 117543 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 12Department of Geology, Kent State University Stark Campus, 6000 Frank Ave. -

Unexpected Diversity in Neelipleona Revealed by Molecular Phylogeny Approach (Hexapoda, Collembola)

S O I L O R G A N I S M S Volume 83 (3) 2011 pp. 383–398 ISSN: 1864-6417 Unexpected diversity in Neelipleona revealed by molecular phylogeny approach (Hexapoda, Collembola) Clément Schneider1, 3, Corinne Cruaud2 and Cyrille A. D’Haese1 1 UMR7205 CNRS, Département Systématique et Évolution, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, CP50 Entomology, 45 rue Buffon, 75231 Paris cedex 05, France 2 Genoscope, Centre National de Sequençage, 2 rue G. Crémieux, CP5706, 91057 Evry cedex, France 3 Corresponding author: Clément Schneider (email: [email protected]) Abstract Neelipleona are the smallest of the four Collembola orders in term of species number with 35 species described worldwide (out of around 8000 known Collembola). Despite this apparent poor diversity, Neelipleona have a worldwide repartition. The fact that the most commonly observed species, Neelus murinus Folsom, 1896 and Megalothorax minimus Willem, 1900, display cosmopolitan repartition is striking. A cladistic analysis based on 16S rDNA, COX1 and 28S rDNA D1 and D2 regions, for a broad collembolan sampling was performed. This analysis included 24 representatives of the Neelipleona genera Neelus Folsom, 1896 and Megalothorax Willem, 1900 from various regions. The interpretation of the phylogenetic pattern and number of transformations (branch length) indicates that Neelipleona are more diverse than previously thought, with probably many species yet to be discovered. These results buttress the rank of Neelipleona as a whole order instead of a Symphypleona family. Keywords: Collembola, Neelidae, Megalothorax, Neelus, COX1, 16S, 28S 1. Introduction 1.1. Brief history of Neelipleona classification The Neelidae family was established by Folsom (1896), who described Neelus murinus from Cambridge (USA). -

Metanephrops Challengeri)

Population genetics of New Zealand Scampi (Metanephrops challengeri) Alexander Verry A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Ecology and Biodiversity. Victoria University of Wellington 2017 Page | I Abstract A fundamental goal of fisheries management is sustainable harvesting and the preservation of properly functioning populations. Therefore, an important aspect of management is the identification of demographically independent populations (stocks), which is achieved by estimating the movement of individuals between areas. A range of methods have been developed to determine the level of connectivity among populations; some measure this directly (e.g. mark- recapture) while others use indirect measures (e.g. population genetics). Each species presents a different set of challenges for methods that estimate levels of connectivity. Metanephrops challengeri is a species of nephropid lobster that supports a commercial fishery and inhabits the continental shelf and slope of New Zealand. Very little research on population structure has been reported for this species and it presents a unique set of challenges compared to finfish species. M. challengeri have a short pelagic larval duration lasting up to five days which limits the dispersal potential of larvae, potentially leading to low levels of connectivity among populations. The aim of this study was to examine the genetic population structure of the New Zealand M. challengeri fishery. DNA was extracted from M. challengeri samples collected from the eastern coast of the North Island (from the Bay of Plenty to the Wairarapa), the Chatham Rise, and near the Auckland Islands. DNA from the mitochondrial CO1 gene and nuclear ITS-1 region was amplified and sequenced. -

Lobsters-Identification, World Distribution, and U.S. Trade

Lobsters-Identification, World Distribution, and U.S. Trade AUSTIN B. WILLIAMS Introduction tons to pounds to conform with US. tinents and islands, shoal platforms, and fishery statistics). This total includes certain seamounts (Fig. 1 and 2). More Lobsters are valued throughout the clawed lobsters, spiny and flat lobsters, over, the world distribution of these world as prime seafood items wherever and squat lobsters or langostinos (Tables animals can also be divided rougWy into they are caught, sold, or consumed. 1 and 2). temperate, subtropical, and tropical Basically, three kinds are marketed for Fisheries for these animals are de temperature zones. From such partition food, the clawed lobsters (superfamily cidedly concentrated in certain areas of ing, the following facts regarding lob Nephropoidea), the squat lobsters the world because of species distribu ster fisheries emerge. (family Galatheidae), and the spiny or tion, and this can be recognized by Clawed lobster fisheries (superfamily nonclawed lobsters (superfamily noting regional and species catches. The Nephropoidea) are concentrated in the Palinuroidea) . Food and Agriculture Organization of temperate North Atlantic region, al The US. market in clawed lobsters is the United Nations (FAO) has divided though there is minor fishing for them dominated by whole living American the world into 27 major fishing areas for in cooler waters at the edge of the con lobsters, Homarus americanus, caught the purpose of reporting fishery statis tinental platform in the Gul f of Mexico, off the northeastern United States and tics. Nineteen of these are marine fish Caribbean Sea (Roe, 1966), western southeastern Canada, but certain ing areas, but lobster distribution is South Atlantic along the coast of Brazil, smaller species of clawed lobsters from restricted to only 14 of them, i.e. -

Population Monitoring of Glenelg Spiny Crayfish (Euastacus Bispinosus ) in Rising-Spring Habitats of Lower South East, South Australia

Population monitoring of Glenelg Spiny Crayfish (Euastacus bispinosus ) in rising-spring habitats of lower south east, South Australia Nick Whiterod and Michael Hammer Aquasave Consultants, Adelaide May 2012 Report to Friends of Mt Gambier Area Parks (Friends of Parks Inc.) Citation Whiterod, N. and Hammer, M. (2012). Population monitoring of Glenelg Spiny Crayfish (Euastacus bispinosus ) in rising-spring habitats of lower south east, South Australia. Report to Friends of Mt Gambier Area Parks (Friends of Parks Inc.). Aquasave Consultants, Adelaide. p. 27. Correspondence in relation to this report contact Dr Nick Whiterod Aquasave Consultants Tel: +61 409 023 771 Email: [email protected] Photographs © N. Whiterod, O. Sweeney, D. Mossop and M. Hammer Cover (clockwise from top): underwater view of aquatic vegetation in the Ewens Pond system; female Glenelg Spiny Crayfish with eggs (in berry); and Glenelg Spiny Crayfish amongst aquatic vegetation. Disclaimer This report was commissioned by Friends of Mt Gambier Area Parks (Friends of Parks Inc.). It was based on the best information available at the time and while every effort has been made to ensure quality, no warranty express or implied is provided for any errors or omissions, nor in the event of its use for any other purposes or by any other parties. ii Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Methods .................................................................................................................................. -

Decapode.Pdf

We are pleased and honored to welcome at the Paléospace Museum of Villers-sur-Mer the “6th Symposium on Mesozoic and Cenozoic Decapod Crustaceans”. Villers-sur-Mer is a place universally known by specialists and amateurs of palaeontology due to its famous Vaches Noires cliffs. Villers-sur-Mer has also the distinction of being the only French seaside resort located on the Greenwich Meridian line. The Paléospace is a Museum funded in 2011 with the label Musée de France. Three main animations linked to the Time are presented: palaeontology, astronomy and nature with the neighbouring marsh. The museum is in a constant evolution. For instance, an exhibition specially dedicated to dinosaurs was opened two years ago and a planetarium will open next summer. Every year a very high quality temporary exhibition takes place during the summer period with very numerous animations during all the year. The Paléospace does not stop progressing in term of visitors (56 868 in 2015) and its notoriety is universally recognized both by the other museums as by the scientific community. We are very proud of these unexpected results. We thank the dynamism and the professionalism of the Paléospace team which is at the origin of this very great success. We wish you a very good stay at Villers-sur-Mer, a beautiful visit of the Paléospace and especially an excellent congress. Jean-Paul Durand, Mayor and President of Paléospace MOT DU MAIRE DE VILLERS-SUR-MER Nous sommes très heureux et très honorés d’accueillir à Villers-sur-Mer, le « 6e Symposium on Mesozoic and Cenozoic Decapod Crustaceans » dans le cadre du Paléospace. -

Part I. an Annotated Checklist of Extant Brachyuran Crabs of the World

THE RAFFLES BULLETIN OF ZOOLOGY 2008 17: 1–286 Date of Publication: 31 Jan.2008 © National University of Singapore SYSTEMA BRACHYURORUM: PART I. AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF EXTANT BRACHYURAN CRABS OF THE WORLD Peter K. L. Ng Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, Kent Ridge, Singapore 119260, Republic of Singapore Email: [email protected] Danièle Guinot Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, Département Milieux et peuplements aquatiques, 61 rue Buffon, 75005 Paris, France Email: [email protected] Peter J. F. Davie Queensland Museum, PO Box 3300, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT. – An annotated checklist of the extant brachyuran crabs of the world is presented for the first time. Over 10,500 names are treated including 6,793 valid species and subspecies (with 1,907 primary synonyms), 1,271 genera and subgenera (with 393 primary synonyms), 93 families and 38 superfamilies. Nomenclatural and taxonomic problems are reviewed in detail, and many resolved. Detailed notes and references are provided where necessary. The constitution of a large number of families and superfamilies is discussed in detail, with the positions of some taxa rearranged in an attempt to form a stable base for future taxonomic studies. This is the first time the nomenclature of any large group of decapod crustaceans has been examined in such detail. KEY WORDS. – Annotated checklist, crabs of the world, Brachyura, systematics, nomenclature. CONTENTS Preamble .................................................................................. 3 Family Cymonomidae .......................................... 32 Caveats and acknowledgements ............................................... 5 Family Phyllotymolinidae .................................... 32 Introduction .............................................................................. 6 Superfamily DROMIOIDEA ..................................... 33 The higher classification of the Brachyura ........................ -

The Magnitude of Global Marine Species Diversity

UC San Diego Other Scholarly Work Title The Magnitude of Global Marine Species Diversity Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2dp082mj Journal Current Biology, 22(23) Author Appeltans, Ward, et al., Publication Date 2012-12-04 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Current Biology 22, 2189–2202, December 4, 2012 ª2012 Elsevier Ltd All rights reserved http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.036 Article The Magnitude of Global Marine Species Diversity Ward Appeltans,1,2,96,* Shane T. Ahyong,3,4 Gary Anderson,5 8WorldFish Center, Los Ban˜ os, Laguna 4031, Philippines Martin V. Angel,6 Tom Artois,7 Nicolas Bailly,8 9ARTOO Marine Biology Consultants, Southampton Roger Bamber,9 Anthony Barber,10 Ilse Bartsch,11 SO14 5QY, UK Annalisa Berta,12 Magdalena Błazewicz-Paszkowycz,_ 13 10British Myriapod and Isopod Group, Ivybridge, Phil Bock,14 Geoff Boxshall,15 Christopher B. Boyko,16 Devon PL21 0BD, UK Simone Nunes Branda˜o,17,18 Rod A. Bray,15 11Research Institute and Natural History Museum, Niel L. Bruce,19,20 Stephen D. Cairns,21 Tin-Yam Chan,22 Senckenberg, Hamburg 22607, Germany Lanna Cheng,23 Allen G. Collins,24 Thomas Cribb,25 12Department of Biology, San Diego State University, Marco Curini-Galletti,26 Farid Dahdouh-Guebas,27,28 San Diego, CA 92182, USA Peter J.F. Davie,29 Michael N. Dawson,30 Olivier De Clerck,31 13Laboratory of Polar Biology and Oceanobiology, University Wim Decock,1 Sammy De Grave,32 Nicole J. de Voogd,33 of Ło´ dz, Ło´ dz 90-237, Poland Daryl P. -

Decapod Crustaceans from the Middle Jurassic Opalinus Clay of Northern Switzerland, with Comments on Crustacean Taphonomy

0012-9402/04/030381-12 Eclogae geol. Helv. 97 (2004) 381–392 DOI 10.1007/s00015-004-1137-2 Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, 2004 Decapod crustaceans from the Middle Jurassic Opalinus Clay of northern Switzerland, with comments on crustacean taphonomy WALTER ETTER Key words: Decapoda, Peracarida, Jurassic, Switzerland, ecology, crustacean taphonomy ABSTRACT ZUSAMMENFASSUNG Four species of decapod crustaceans from the Middle Jurassic Opalinus Clay Aus dem Opalinuston (Mittlerer Jura, Aalenian) der Nordschweiz werden vier (Aalenian) of Northern Switzerland are described. Of these, Mecochirus cf. Arten von decapoden Krebsen beschrieben. Von Aeger sp., Eryma cf. bedelta eckerti is the most common one, while Eryma cf. bedelta, Glyphea sp. and und Glyphaea sp. wurden nur ganz wenige Exemplaren gefunden, während Aeger sp. were present as individuals, or only a few specimens. The preserva- Mecochirus cf. eckerti etwas häufiger ist. Die Erhaltungsbedingungen waren tion of these crustaceans ranges from moderate to excellent, reflecting the während der Ablagerung des Opalinustones günstig, was sich in einer geringen favourable taphonomic conditions of the depositional environment. An inter- Disartikulations- und Fragmentationsrate der Krebse widerspiegelt. Ein in- esting aspect of the taphocoenosis in the Opalinus Clay is that the decapod teressanter Aspekt der Taphocoenose ist die deutliche Dominanz der Klein- crustaceans are by far outnumbered by small peracarid crustaceans (isopods krebse (Peracarida: Isopoden und Tanaidaceen). Dies dürfte die Zahlenver- and tanaids). This is interpreted as reflecting the original differences in abun- hältnisse der ehemaligen Lebensgemeinschaft widerspiegeln. In den meisten dance. Yet this distribution is not frequently encountered in sedimentary se- Ablagerungen dominieren jedoch die decapoden Krebse, wogegen Peracarida quences where decapods (although rare) are far more common than isopods äusserst selten sind. -

How to Become a Crab: Phenotypic Constraints on a Recurring Body Plan

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 25 December 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202012.0664.v1 How to become a crab: Phenotypic constraints on a recurring body plan Joanna M. Wolfe1*, Javier Luque1,2,3, Heather D. Bracken-Grissom4 1 Museum of Comparative Zoology and Department of Organismic & Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, 26 Oxford St, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 2 Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Balboa–Ancon, 0843–03092, Panama, Panama 3 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520-8109, USA 4 Institute of Environment and Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, Biscayne Bay Campus, 3000 NE 151 Street, North Miami, FL 33181, USA * E-mail: [email protected] Summary: A fundamental question in biology is whether phenotypes can be predicted by ecological or genomic rules. For over 140 years, convergent evolution of the crab-like body plan (with a wide and flattened shape, and a bent abdomen) at least five times in decapod crustaceans has been known as ‘carcinization’. The repeated loss of this body plan has been identified as ‘decarcinization’. We offer phylogenetic strategies to include poorly known groups, and direct evidence from fossils, that will resolve the pattern of crab evolution and the degree of phenotypic variation within crabs. Proposed ecological advantages of the crab body are summarized into a hypothesis of phenotypic integration suggesting correlated evolution of the carapace shape and abdomen. Our premise provides fertile ground for future studies of the genomic and developmental basis, and the predictability, of the crab-like body form. Keywords: Crustacea, Anomura, Brachyura, Carcinization, Phylogeny, Convergent evolution, Morphological integration 1 © 2020 by the author(s). -

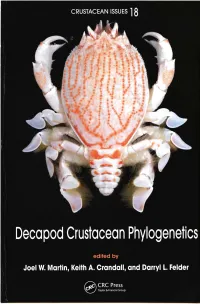

Decapod Crustacean Phylogenetics

CRUSTACEAN ISSUES ] 3 II %. m Decapod Crustacean Phylogenetics edited by Joel W. Martin, Keith A. Crandall, and Darryl L. Felder £\ CRC Press J Taylor & Francis Group Decapod Crustacean Phylogenetics Edited by Joel W. Martin Natural History Museum of L. A. County Los Angeles, California, U.S.A. KeithA.Crandall Brigham Young University Provo,Utah,U.S.A. Darryl L. Felder University of Louisiana Lafayette, Louisiana, U. S. A. CRC Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Croup, an informa business CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group 6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300 Boca Raton, Fl. 33487 2742 <r) 2009 by Taylor & Francis Group, I.I.G CRC Press is an imprint of 'Taylor & Francis Group, an In forma business No claim to original U.S. Government works Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 109 8765 43 21 International Standard Book Number-13: 978-1-4200-9258-5 (Hardcover) Ibis book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. Reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable data and information, but the author and publisher cannot assume responsibility for the valid ity of all materials or the consequences of their use. The authors and publishers have attempted to trace the copyright holders of all material reproduced in this publication and apologize to copyright holders if permission to publish in this form has not been obtained. If any copyright material has not been acknowledged please write and let us know so we may rectify in any future reprint. Except as permitted under U.S. Copyright Faw, no part of this book maybe reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or uti lized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopy ing, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publishers. -

Short Note Records of Hippa Strigillata (Stimpson, 1860) (Crustacea: Decapoda: Hippidae) in the SE Gulf of California, Mexico

Nauplius 22(1): 63-65, 2014 63 Short Note Records of Hippa strigillata (Stimpson, 1860) (Crustacea: Decapoda: Hippidae) in the SE Gulf of California, Mexico Daniela Ríos-Elósegui and Michel E. Hendrickx* (DRE) Posgrado en Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Unidad Académica Mazatlán, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, P.O. Box 811, Mazatlán, Sinaloa 82000, Mexico. E-mail: [email protected] (DRE, MEH) Laboratorio de Invertebrados Bentónicos, Unidad Académica Mazatlán, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, P.O. Box 811, Mazatlán, Sinaloa 82000, Mexico. E-mail: [email protected]; *Corresponding author ABSTRACT - This paper presents details regarding the collections and records of H. strigillata in the Bay of Mazatlán, SE Gulf of California, Mexico. Samples of H. strigillata were obtained in this bay and suroundings area during different periods and deposited in the collection of UNAM, Mazatlán. Morphometric data, distribution, biological and ecological data were furnished. Key words: Distribution, Gulf of California, Hippa, mole crab Because they represent a very dynamic synonym of Remipes pacificus Dana, 1852) environment, often with high energy wave (Boyko, 2002, Boyko and McLaughlin, action, sandy beaches are considered low 2010) and H. strigillata (Stimpson, 1860) diversity habitats for macro and mega fauna (Hendrickx, 1995; Hendrickx and Harvey, (Tait, 1972). This is particularly true along the 1999). Hippa marmorata occurs from the west coast of Mexico (Dexter, 1976; Hendrickx, central Gulf of California to Colombia, 1996). The intertidal habitat is mostly including several oceanic islands of the eastern dominated by species of bivalve mollusks and Pacific (Revillagigedo, del Coco, Galapagos, small (Amphipoda, Isopoda) to medium size and Clipperton) (Hendrickx, 2005).