Hermann Hesse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

© 2010 Julia Silvia Feldhaus ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2010 Julia Silvia Feldhaus ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Between Commodification and Emancipation: Image Formation of the New Woman through the Illustrated Magazine of the Weimar Republic By Julia Silvia Feldhaus A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School – New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in German Written under the direction of Martha B. Helfer And Michael G. Levine And approved by ____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October 2010 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Between Commodification and Emancipation: Image Formation of the New Woman through the Illustrated Magazine of the Weimar Republic By JULIA SILVIA FELDHAUS Dissertation Directors: Martha B. Helfer Michael G. Levine This dissertation investigates the conflict between the powerful emancipatory image of the New Woman as represented in the illustrated magazines of the Weimar Republic and the translation of this image into a lifestyle acted out by women during this era. I argue that while female journalists promote the image of the New Woman in illustrated magazines as a liberating opening onto self-determination and self- management, this very image is simultaneously and paradoxically oppressive. For women to shake off the inheritance of a patriarchal past, they must learn to adjust to a new identity, one that is still to a large extent influenced by and in the service of men. The ideal beauty image designed by female journalists as a framework for emancipation in actuality turned into an oppressive normalization in professional and social markets in which traditional rules no longer obtained. -

To Children I Give My Heart Vasily

TO CHILDREN I GIVE MY HEART VASILY SUKHOMLINSKY (Translated from the Russian by Holly Smith) From the Publishers Vasily Alexandrovich Sukhomlinsky (1918-1970) devoted thirty-five years of his short life to the upbringing and instruction of children. For twenty-nine years he was director of a school in the Ukrainian village of Pavlysh, far away from the big cities. For his work in education, he was awarded the titles of Hero of Socialist Labour and Merited Teacher of the Ukrainian SSR; and elected Corresponding Member of the Academy of Pedagogical Science of the USSR. What is the essence of Vasily Sukhomlinsky's work as an educator? Progressive educators have long tried to merge upbringing and instruction into one educational process. This dream was realized in the educational work of Sukhomlinsky. To see an individual in every school child - this was the essence of his educational method and a necessary requirement for anyone who hopes to raise and teach children. Vasily Sukhomlinsky showed in theory and practice that any healthy child can get a modern secondary education in an ordinary public school without any separation of children into group of bright and less bright. This was no new discovery. But he found the sensible mean that enable, the teacher to lead the child to knowledge in keeping with the national educational programme. The main thing for Sukhomlinsky was to awaken the child's desire to learn, to develop a taste for self-education and self-discipline. Sukhomlinsky studied each of his pupils, consulting with the other teachers and with the parents, comparing his own thoughts with the views of the great educators of the past and with folk wisdom. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

The Death of Christian Culture

Memoriœ piœ patris carrissimi quoque et matris dulcissimœ hunc libellum filius indignus dedicat in cordibus Jesu et Mariœ. The Death of Christian Culture. Copyright © 2008 IHS Press. First published in 1978 by Arlington House in New Rochelle, New York. Preface, footnotes, typesetting, layout, and cover design copyright 2008 IHS Press. Content of the work is copyright Senior Family Ink. All rights reserved. Portions of chapter 2 originally appeared in University of Wyoming Publications 25(3), 1961; chapter 6 in Gary Tate, ed., Reflections on High School English (Tulsa, Okla.: University of Tulsa Press, 1966); and chapter 7 in the Journal of the Kansas Bar Association 39, Winter 1970. No portion of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review, or except in cases where rights to content reproduced herein is retained by its original author or other rights holder, and further reproduction is subject to permission otherwise granted thereby according to applicable agreements and laws. ISBN-13 (eBook): 978-1-932528-51-0 ISBN-10 (eBook): 1-932528-51-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Senior, John, 1923– The death of Christian culture / John Senior; foreword by Andrew Senior; introduction by David Allen White. p. cm. Originally published: New Rochelle, N.Y. : Arlington House, c1978. ISBN-13: 978-1-932528-51-0 1. Civilization, Christian. 2. Christianity–20th century. I. Title. BR115.C5S46 2008 261.5–dc22 2007039625 IHS Press is the only publisher dedicated exclusively to the social teachings of the Catholic Church. -

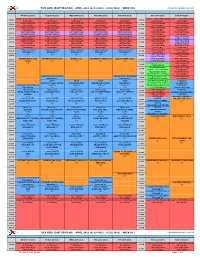

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO -

Memorabilia Mislabeled Online Tickets Sell Monday Afternoon

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons October 2007 10-2-2007 The aiD ly Gamecock, TUESDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2007 University of South Carolina, Office oftude S nt Media Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/gamecock_2007_oct Recommended Citation University of South Carolina, Office of Student Media, "The aiD ly Gamecock, TUESDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2007" (2007). October. 19. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/gamecock_2007_oct/19 This Newspaper is brought to you by the 2007 at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in October by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sports The Mix Local News..............2 TODAY Wednesday Opinion................... 4 Daily Gamecock breaks down the ‘Feast of Love’ isn’t much of a feast Puzzles....................6 midseason SEC standings while USC after all. See what we thought of the Comics.....................6 Horoscopes...............6 prepares for Kentucky at home. See page 7 movie in The Mix. See page 5 Classifi ed.................8 85 66 87 67 dailygamecock.com THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA TUESDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2007 VOL. 101, NO. 28 ● SINCE 1908 Student football Memorabilia mislabeled online tickets sell Monday afternoon. Jerseys allegedly worn Both jerseys are black uniforms with the out quickly by now-NFL players interlocking “USC” symbol NEW OLD proven illegitimate on the sleeve and “Carolina” written across the chest, Competitive schedule, a design which Holtz Alex Riley created upon his arrival in winning season contribute SPORTS EDITOR 1999. However, the telling to brisk distribution rate difference between the 1999 Two jerseys being jerseys and later uniforms On Wednesdays, you can auctioned off by USC worn by the Gamecocks are 55/57 South Carolina still walk over to the Grand through the athletics the Russell Athletic logos on Football Jersey.” Market Place and get a hot department Web site are not the upper right side. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 The Laws of Fantasy Remix Matthew J. Dauphin Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE LAWS OF FANTASY REMIX By MATTHEW J. DAUPHIN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 Matthew J. Dauphin defended this dissertation on March 29, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Barry Faulk Professor Directing Dissertation Donna Marie Nudd University Representative Trinyan Mariano Committee Member Christina Parker-Flynn Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To every teacher along my path who believed in me, encouraged me to reach for more, and withheld judgment when I failed, so I would not fear to try again. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ v 1. AN INTRODUCTION TO FANTASY REMIX ...................................................................... 1 Fantasy Remix as a Technique of Resistance, Subversion, and Conformity ......................... 9 Morality, Justice, and the Symbols of Law: Abstract -

MAM Resume PAGES Copy

Mitchell Actors & Models Wes Deitrick 509-720-8312 (Spokane) 206-249-9051 (Seattle) SAG-AFTRA AEA Dual Citizen USA and Canada [email protected] HEIGHT:5’ 10” HAIR: SILVER EYES: BLUE FILM & TELEVISION Grimm Ep. 607 - Blind Love Willard Goode NBC / Aaron Lipstadt The River Murders Sully NxNW - Rich Cowan Finding Bliss Talent Agent NxNW - Julie Davis A Thousand Years Of Good Prayers Antique Store Owner NxNW - Wayne Wang Home Of The Brave Viet Nam Veteran NxNW - Irwin Winkler May Day FBI agent - Dix Wenger Productions - Ron Ford Guyver II Volker Guyver Productions - Steve Wang Mr. Dark Series Captain Nick Thorson JJH Productions - Jesse James Hennessey More at IMDB https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0215141/?ref_=nv_sr_1 COMMERCIALS Upon Request THEATRE Freud's Last Session Sigmund Freud Public Theater of San Antonio Other Desert Cities Lyman Wyatt Interplayers Frost-Nixon Richard M. Nixon Firth Chew Theater Our Town (Adaptation) Editor Webb, Stimpson, Others Interplayers Ecanaba In The Moonlight Albert Soady Spokane Civic Theater Long Day’s Journey Into Night James Tyrone Actors Repertory Theater Hamlet Hamlet California Shakespeare Company Masters Of The Sea Redmond San Diego Old Globe Theater Vessel Of Ixchel Colorado Smith Norwegian Cruise Lines SPECIAL SKILLS Dialects: British, Southern, Irish, Stage Combat, Fire Arms, Green Screen, Improv, Frisbee, Horseback Riding, Swimming, Pilates, Weightlifting, Running, Baseball, Football, Juggling TRAINING Sanford Meisner Acting Technique Stella Adler Acting Technique Acting For Camera Tony Barr’s Film Acting Workshop, N. Hollywood - David Paymer and Tony Barr Voice Acting Paul Liberti. -

A Hermeneutic Reading of Natalie Barney and Renee Vivien

Anthós (1990-1996) Volume 1 Number 5 Article 7 1996 A Hermeneutic Reading of Natalie Barney and Renee Vivien Antoinette Sherman Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anthos_archives Part of the Philosophy Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sherman, Antoinette (1996) "A Hermeneutic Reading of Natalie Barney and Renee Vivien," Anthós (1990-1996): Vol. 1 : No. 5 , Article 7. Available at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/anthos_archives/vol1/iss5/7 This open access Article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). All documents in PDXScholar should meet accessibility standards. If we can make this document more accessible to you, contact our team. A Hermeneutic Reading of Natalie Barney and Renee Vivien Antoinette Sherman "The word 'hermeneutics' points back, as we know, to the task of the interpreter, which is that of interpreting and communicating something which is unintelligible because it is spoken in a foreign language-even if it is the language of the signs and symbols of the Gods." -Gadamer, Truth and Method My intention in focusing upon the works of Renee Vivien and Natalie Barney is to make more widely known two fine writ ers whose neglect can in part be attributed to their sex and unconventional lifestyles and to examine how and why these women emerged as rare exceptions at the turn of the century. This work is not motivated by a desire to resurrect two forgotten women writers or create a new canon of women's literature; rather, it is done under the belief that the consideration of women writer's (or any other minority) can be beneficial to expanding and altering attitudes, prejudices and ideologies. -

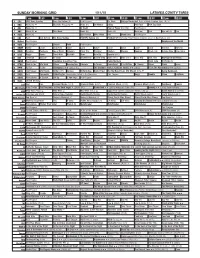

Sunday Morning Grid 1/11/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/11/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Dr. Chris College Basketball Duke at North Carolina State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) On Money Skiing PGA Tour PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football NFC Divisional Playoff Dallas Cowboys at Green Bay Packers. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Employee of the Month 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Revenge of the Nerds 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Pablo Montero Hotel Todo Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

![Journal of the Short Story in English, 52 | Spring 2009, « General Issue » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Juin 2011, Consulté Le 03 Décembre 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7873/journal-of-the-short-story-in-english-52-spring-2009-%C2%AB-general-issue-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-01-juin-2011-consult%C3%A9-le-03-d%C3%A9cembre-2020-4897873.webp)

Journal of the Short Story in English, 52 | Spring 2009, « General Issue » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Juin 2011, Consulté Le 03 Décembre 2020

Journal of the Short Story in English Les Cahiers de la nouvelle 52 | Spring 2009 General issue Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/935 ISSN : 1969-6108 Éditeur Presses universitaires de Rennes Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 juin 2009 ISSN : 0294-04442 Référence électronique Journal of the Short Story in English, 52 | Spring 2009, « General issue » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 01 juin 2011, consulté le 03 décembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/935 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 3 décembre 2020. © All rights reserved 1 SOMMAIRE Foreword Linda Collinge-Germain et Emmanuel Vernadakis Dangerous Similitude in Charles Dickens’ “To Be Read at Dusk” Kimberley Jackson A History of the American Mind: "Young Goodman Brown" Steven Olson 'The Half Shall Remain Untold': Hunilla of Melville's Encantadas K. M. Wheeler Linguistic Structure and Rhetorical Resolution in Katherine Mansfield "The Garden Party" Stephen E. Severn La tentation mélancolique dans One Warm Saturday de Dylan Thomas Claude Maisonnat Identity is a Slippery Fish – the Discovery of Identity in Elizabeth Bowen's Short Story "The Demon Lover" Zuzanna Zarebska Sanches Cultural In-Betweenness in "L'expulsé"/"The Expelled" by Samuel Beckett Linda Collinge-Germain Index Nominorum, Issues 41-51 Index Nominum personarum, Issues 41-51 “Echo's Bones": Samuel Beckett's Lost Story of Afterlife José Francisco Fernández Samuel Beckett's maternal passion or hysteria at work in company/compagnie Pascale Sardin Raymond Carver's "Myers trio" Robert Miltner Saroyan's lonely fruitcakes, and other goofs: strategies of resistance to the culture of abundance Mauricio D. -

Hemingway (Ernew; Salimger (J,P); Steinbeck (John)

OCUMENT RESUME ED 226 366 CS 207 373 AUTHOR Workman, Brooke TITLE Writing Seminars in the Content Area: In Search of Hemingway, Salinger, and Steinbeck. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-5886-2 PUB DATE 83 NOTE 325p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers ok English, 1111 Kenyon Rd.; Urbana,'IL 61801 (Stock No: 58862, $12.00 member,',$13.75 non-member). PUB TYPE Guides'- Classroom Use Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF0l/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authos;.English Instruction; Higher Education; - Instructional Materials; Literature Appreciation; Secondary Education; *Seminars; Teaching Methods; *Thematic Approach; *United States Literature; , Writing (Composition); *Writing Instruction IDENTIFIERS Hemingway (ErneW; Salimger (J,p); Steinbeck (John) ABSTRACT Intended for High school and college literature instructors, this book contains meterialt for intensive semester-long seminars on, the lives and works of three American authors: Emest Hemingway, J. D. Salinger, and John Steinbeck. Each seminar revolves around seven papers the students are required to write and defend aloud in front of the i.est of the class. Classmates then assign and discuss a grade for each paper. Following an introduction discussing each step of the seminar method and the sequence of writing skills, the boot: is divided into three sections, one for eabh author. Each section contains a daily schedule for the seminar, a chronology of the author's life, and the materials and procedures for reading and writing a pa er for each work studied. Models for the student papers are included. ppendixes at the end of each section contain extensive chronologies n time-line fashion, essays relevant to the author's works, and a trimester or 60-day seminar schedule.