A Personal Reminiscence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Hundred Years of British Piano Miniatures Butterworth • Fricker • Harrison Headington • L

WORLD PREMIÈRE RECORDINGS A HUNDRED YEARS OF BRITISH PIANO MINIATURES BUTTERWORTH • FRICKER • HARRISON HEADINGTON • L. & E. LIVENS • LONGMIRE POWER • REYNOLDS • SKEMPTON • WARREN DUNCAN HONEYBOURNE A HUNDRED YEARS OF BRITISH PIANO MINIATURES BUTTERWORTH • FRICKER • HARRISON • HEADINGTON L. & E. LIVENS • LONGMIRE • POWER • REYNOLDS SKEMPTON • WARREN DUNCAN HONEYBOURNE, piano Catalogue Number: GP789 Recording Date: 25 August 2015 Recording Venue: The National Centre for Early Music, St Margaret’s Church, York, UK Producers: David Power and Peter Reynolds (1–21), Peter Reynolds and Jeremy Wells (22–28) Engineer: Jeremy Wells Editors: David Power and Jeremy Wells Piano: Bösendorfer 6’6” Grand Piano (1999). Tuned to modern pitch. Piano Technician: Robert Nutbrown Booklet Notes: Paul Conway, David Power and Duncan Honeybourne Publishers: Winthrop Rogers Ltd (1, 3), Joseph Williams Ltd (2), Unpublished. Manuscript from the Michael Jones collection (4), Comus Edition (5–7), Josef Weinberger Ltd (8), Freeman and Co. (9), Oxford University Press (10, 11), Unpublished. Manuscript held at the University of California Santa Barbara Library (12, 13), Unpublished (14–28), Artist Photograph: Greg Cameron-Day Cover Art: Gro Thorsen: City to City, London no 23, oil on aluminium, 12x12 cm, 2013 www.grothorsen.com LEO LIVENS (1896–1990) 1 MOONBEAMS (1915) 01:53 EVANGELINE LIVENS (1898–1983) 2 SHADOWS (1915) 03:15 JULIUS HARRISON (1885–1963) SEVERN COUNTRY (1928) 02:17 3 III, No. 3, Far Forest 02:17 CONSTANCE WARREN (1905–1984) 4 IDYLL IN G FLAT MAJOR (1930) 02:45 ARTHUR BUTTERWORTH (1923–2014) LAKELAND SUMMER NIGHTS, OP. 10 (1949) 10:07 5 I. Evening 02:09 6 II. Rain 02:30 7 III. -

ONYX4206.Pdf

EDWARD ELGAR (1857–1934) Sea Pictures Op.37 The Music Makers Op.69 (words by Alfred O’Shaughnessy) 1 Sea Slumber Song 5.13 (words by Roden Noel) 6 Introduction 3.19 2 In Haven (Capri) 1.52 7 We are the music makers 3.56 (words by Alice Elgar) 8 We, in the ages lying 3.59 3 Sabbath Morning at Sea 5.24 (words by Elizabeth Barrett Browning) 9 A breath of our inspiration 4.18 4 Where Corals Lie 3.43 10 They had no vision amazing 7.41 (words by Richard Garnett) 11 But we, with our dreaming 5 The Swimmer 5.50 and singing 3.27 (words by Adam Lindsay Gordon) 12 For we are afar with the dawning 2.25 Kathryn Rudge mezzo-soprano 13 All hail! we cry to Royal Liverpool Philharmonic the corners 9.11 Orchestra & Choir Vasily Petrenko Pomp & Circumstance 14 March No.1 Op.39/1 5.40 Total timing: 66.07 Artist biographies can be found at onyxclassics.com EDWARD ELGAR Nowadays any listener can make their own analysis as the Second Symphony, Violin Sea Pictures Op.37 · The Music Makers Op.69 Concerto and a brief quotation from The Apostles are subtly used by Elgar to point a few words in the text. Otherwise, the most powerful quotations are from The Dream On 5 October 1899, the first performance of Elgar’s song cycle Sea Pictures took place in of Gerontius, the Enigma Variations and his First Symphony. The orchestral introduction Norwich. With the exception of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, all the poets whose texts Elgar begins in F minor before the ‘Enigma’ theme emphasises, as Elgar explained to Newman, set in the works on this album would be considered obscure -

ARPCD 0403 Elgar

EDWARD ELGAR THE DREAM OF GERONTIUS JON VICKERS CONSTANCE SHACKLOCK MARIAN NOWAKOWSKI ORCHESTRA SINFONICA E CORO DI ROMA DELLA RAI SIR JOHN BARBIROLLI ROMA, 20.11.1957 ARCHIPEL DESERT ISLAND COLLECTION Edward Elgar (1857-1934) The Dream of Gerontius Op. 38 Oratorio for mezzo-soprano, tenor, bass, full choir and orchestra, based on the poem by Cardinal John Newman CD 1 74:54 CD 2 73:21 Part One Part Two (Cont.) [1] Prelude 10:27 [1] Thy judgment is now near (Angel, Soul of Gerontius) 3:26 [2] Jesu, Maria - I am near to death (Gerontius) 3:23 [2] Jesu! By that shuddering dread (Angel of Agony, Soul of Ger.) 6:07 [3] Kyrie eleison. Holy Mary, pray for him (Chorus) 2:34 [3] Praise to His Name! (Angel) 1:38 [4] Rouse thee, my fainting soul (Gerontius) 0:44 [4] Take me away (Soul of Gerontius) 3:38 [5] Be merciful, be gracious (Chorus) 3:29 [5] Lord, Thou hast been our refuge (Chorus) 1:11 [6] Sanctus fortis, Sanctus Deus (Gerontius) 5:10 [6] Softly and gently, dearly-ransomed soul (Angel, Chorus) 6:22 [7] I can no more (Gerontius) 2:00 [8] Rescue him, O Lord (Gerontius, Chorus) 2:27 [9] Novissima hora est (Gerontius) 1:31 [10] Profisciscere, anima Christiana (Priest) 1:45 BONUS: Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) [11] Go, in the name of Angels and Archangels (Chorus, Priest) 4:44 Symphonie fantastique Op. 14 Part Two [12] Prelude 1:57 [7] Rêveries - Passions 14:04 [13] I went to sleep (Soul of Gerontius) 4:11 [8] Un Bal 6:32 [14] My work is done (Angel, Soul of Gerontius) 8:53 [9] Scène aux Champs 16:04 [15] Low-born clods of brute earth (Chorus, Angel) 2:06 [10] Marche au supplice 4:36 [16] The mind bold and independent (Chorus) 2:37 [11] Songe d’une Nuit de Sabbat 9:38 [17] I see not those false spirits (Soul of Gerontius, Angel) 3:19 [18] Praise to the Holiest (Angel, Chorus) 3:28 The Hallé Orchestra [19] Glory to him (Chorus, Angel, Soul of Gerontius) 2:46 Sir John Barbirolli [20] Praise to the Holiest in the height (Chorus) 7:14 Recording: 02.01.1947. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

The Dream of Gerontius. a Musical Analysis

The Dream of Gerontius. A Musical Analysis A Musical Tour of the Work conducted by Frank Beck One of Elgar's favourite walks while writing Gerontius was from his cottage, Birchwood Lodge, down this lane to the village of Knightwick. 'The trees are singing my music,' Elgar wrote. "Or have I sung theirs?" (Photograph by Ann Vernau) "The poem has been soaking in my mind for at least eight years," Elgar told a newspaper reporter during the summer of 1900, just weeks before the première ofThe Dream of Gerontius in Birmingham. Those eight years were crucial to Elgar's development as a composer. From 1892 to 1900 he wrote six large-scale works for voices, beginning with The Black Knight in 1892 and including King Olaf in 1896, Caractacus in 1898 and Sea Pictures in 1899. He also conducted the premières of each one, gaining valuable experience in the practical side of vocal music. Most importantly, perhaps, he gained confidence, particularly after the great success of the Enigma Variations in 1899 made him a national figure. At forty-two, Elgar had waited long for recognition, and he now felt able to take on a subject that offered an imaginative scope far beyond anything he had done before: Cardinal Newman's famous poem of spiritual discovery. Elgar set slightly less than half of the poem, cutting whole sections and shortening others to focus on its central narrative: the story of a man's death and his soul's journey into the next world. Part 1 Gerontius is written for tenor, mezzo-soprano, bass, chorus and orchestra. -

Season 2012-2013

27 Season 2012-2013 Thursday, December 13, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, December 14, at 8:00 Saturday, December 15, Gianandrea Noseda Conductor at 8:00 Alisa Weilerstein Cello Borodin Overture to Prince Igor Elgar Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85 I. Adagio—Moderato— II. Lento—Allegro molto III. Adagio IV. Allegro—Moderato—[Cadenza]—Allegro, ma non troppo—Poco più lento—Adagio—Allegro molto Intermission Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 3 in D major, Op. 29 (“Polish”) I. Introduzione ed allegro: Moderato assai (tempo di marcia funebre)—Allegro brillante II. Alla tedesca: Allegro moderato e semplice III. Andante elegiaco IV. Scherzo: Allegro vivo V. Finale: Allegro con fuoco (tempo di polacca) This program runs approximately 1 hour, 55 minutes. The December 14 concert is sponsored by Medcomp. 228 Story Title The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin Renowned for its distinctive vivid world of opera and Orchestra boasts a new sound, beloved for its choral music. partnership with the keen ability to capture the National Centre for the Philadelphia is home and hearts and imaginations Performing Arts in Beijing. the Orchestra nurtures of audiences, and admired The Orchestra annually an important relationship for an unrivaled legacy of performs at Carnegie Hall not only with patrons who “firsts” in music-making, and the Kennedy Center support the main season The Philadelphia Orchestra while also enjoying a at the Kimmel Center for is one of the preeminent three-week residency in the Performing Arts but orchestras in the world. Saratoga Springs, N.Y., and also those who enjoy the a strong partnership with The Philadelphia Orchestra’s other area the Bravo! Vail Valley Music Orchestra has cultivated performances at the Mann Festival. -

Vol. 13, No.2 July 2003

Chantant • Reminiscences • Harmony Music • Promenades • Evesham Andante • Rosemary (That's for Remembrance) • Pastourelle • Virelai • Sevillana • Une Idylle • Griffinesque • Ga Salut d'Amour • Mot d'AmourElgar • Bizarrerie Society • O Happy Eyes • My Dwelt in a Northern Land • Froissart • Spanish Serenade • La Capricieuse • Serenade • The Black Knight • Sursum Corda • T Snow • Fly, Singing Birdournal • From the Bavarian Highlands • The of Life • King Olaf • Imperial March • The Banner of St George Deum and Benedictus • Caractacus • Variations on an Origina Theme (Enigma) • Sea Pictures • Chanson de Nuit • Chanson Matin • Three Characteristic Pieces • The Dream of Gerontius Serenade Lyrique • Pomp and Circumstance • Cockaigne (In London Town) • Concert Allegro • Grania and Diarmid • May S Dream Children • Coronation Ode • Weary Wind of the West • • Offertoire • The Apostles • In The South (Alassio) • Introduct and Allegro • Evening Scene • In Smyrna • The Kingdom • Wan Youth • How Calmly the Evening • Pleading • Go, Song of Mine Elegy • Violin Concerto in B minor • Romance • Symphony No Hearken Thou • Coronation March • Crown of India • Great is t Lord • Cantique • The Music Makers • Falstaff • Carissima • So The Birthright • The Windlass • Death on the Hills • Give Unto Lord • Carillon • Polonia • Une Voix dans le Desert • The Starlig Express • Le Drapeau Belge • The Spirit of England • The Fring the Fleet • The Sanguine Fan • ViolinJULY Sonata 2003 Vol.13, in E minor No.2 • Strin Quartet in E minor • Piano Quintet in A minor • Cello Concerto -

The Dream of Gerontius by Cardinal Newman

Cardinal Newman’s Dream of Gerontius as a Revelation of the Destiny of the Human Person Fr Thomas Norris The Creed of Christians includes the statement, "I look for the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come." John Henry Newman not only had a vivid sense of that world, a world above and beyond this one, he continually reminded himself and others of the Invisible World or, as he liked to call it, the "Unseen World." The Unseen World held a fascination for him. As a teenager, at the age of fifteen, he had had a profound experience of his Creator and himself. In reading the text of the Dream of Gerontius, it is vital to remember that his elegant language is entirely at the service of belief, the belief in the soul's passage through death to judgement and entry into purgatory on course to eternal communion with the God of Jesus Christ and with all those in the communion of his crucified and risen Body. In this conference, I propose doing the following. First, I will give a brief first report on a recent conference held in London to explore how the idea of Purgatory could work in contemporary psychotherapy. Much common ground was found, particularly in relation to the themes of pride, hope and love. Then we shall briefly indicate the context in which the Dream was written. In the third place, we shall expound the central theme of the Dream, the person dying and finding himself on the way to judgement, supported by prayer on earth and the angels at the approach to the throne of God on high. -

Download Booklet

ADVENT LIVE - Volume 2 o Deo gracias Benjamin Britten (1913-1976), [1.14] arr. Julius Harrison (1885-1963) 1 I am the day Jonathan Dove (b. 1959) [6.35] p Einklang Hugo Wolf (1860-1903) [1.59] 2 Bŏgŏroditsye Dyevo Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) [1.17] a Hymn – Lo! he comes with clouds descending Tune: Helmsley, Descant: [5.09] 3 A Spotless Rose Herbert Howells (1892-1983) [3.30] Christopher Robinson (b. 1936) * 4 A Prayer to St John the Baptist Cecilia McDowall (b. 1951) [4.08] s Chorale Prelude ‘Nun komm, Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) [3.11] 5 * Vox clara ecce intonat Gabriel Jackson (b. 1962) [4.53] der Heiden Heiland’, BWV 661 6 The last and greatest Herald * John McCabe (1939-2015) [5.49] Total timings: [62.59] 7 - 8 Antiphons – O Wisdom; O Adonai Traditional [1.48] * Commissioned for the College Choir 9 A tender shoot Otto Goldschmidt (1829-1907) [2.01] 0 Es ist ein Ros entsprungen Hugo Distler (1908-1942) [1.23] q Out of your sleep Anthony Milner (1925-2002) [2.49] w * An introduction to Hark, the glad sound Judith Bingham (b. 1952) THE CHOIR OF ST JOHN’S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE Hymn – Hark, the glad sound Tune: Bristol [5.28] JAMES ANDERSON-BESANT ORGAN (2019) GLEN DEMPSEY ORGAN (2018) e There is no rose Elizabeth Maconchy (1907-1994) [1.52] TIMOTHY RAVALDE ORGAN (2008) ANNE DENHOLM HARP TRACK 19 r - t Antiphons – O Root of Jesse; O Key of David Traditional [1.49] JAKOB LINDBERG ARCHLUTE TRACK 16 IGNACIO MAÑÁ MESAS SOPRANO SAXOPHONE TRACKS 5 & 12 ANDREW NETHSINGHA DIRECTOR y Ach so laß von mir dich finden Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) [3.22] Each work was recorded live as part of the St John’s College Advent Service in the following years u E’en so, Lord Jesus, quickly come Paul Manz (1919-2009) [2.48] 2008 6 | 2018 2, 3, 4, 5, 13, 16, 17, 18, 20 | 2019 1, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 19, 21, 22 i The Linden Tree Carol Traditional, arr. -

Journal November 1998

T rhe Elgar Society JOURNAL I'- r The Elgar Society Journal 107 MONKHAMS AVENUE, WOODFORD GREEN, ESSEX IG8 OER Tel: 0181 -506 0912 Fax:0181 - 924 4154 e-mail: hodgkins @ compuserve.com CONTENTS Vol.lO, No.6 November 1998 Articles Elgar & Gerontius... Part II 258 ‘Elgar’s Favourite Picture’ 285 A Minor Elgarian Enigma Solved 301 Thoughts from the Three Choirs Festival 1929 305 Obituary: Anthony Leighton Thomas 307 More on Elgar/Payne 3 307 Book Reviews 313 Record Reviews 316 Letters 324 100 years ago... 327 I 5 Front cover: Elgar photographed at Birchwood on 3 August 1900, just after completing 3 The Dream of Gerontius. The photo was taken by William Eller, whom Elgar met through their mutual friend, Richard Arnold. **********=)=*****H:****H==HH:************:(=***=t:*****M=****=|i******************=|c* The Editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. ELGAR SOCIETY JOURNAL ISSN 0143 - 1269 « ELGAR & GERONTIUS: the early performances Lewis Foreman Part II Ludwig Wiillner We should note that there were two Wullners. Ludwig was the singer and actor; Franz was his father, the Director of the Cologne Conservatoire and conductor of the Gurzenich Concerts. He was there at Diisseldorf and promised to consider Gerontius for a concert in 1902, but I cannot trace that it ever took place. We need to consider Ludwig Wullner, for he would sing Gerontius again on two further key occasions, the second Diisseldorf performance at the Lower Rhine Festival in May 1902, and then in London at Westminster Cathedral in June 1903, as well as the Liverpool premiere in March 1903. -

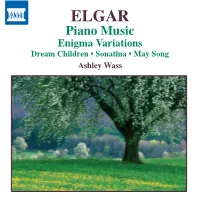

ELGAR Piano Music Enigma Variations

570166bk Elgar US 9/7/06 8:43 pm Page 5 6, Ysobel, is the viola-player Isabel Fitton; Variation 7, Basil Nevinson, an amateur cellist; Variation 13, ***, is Ashley Wass Troyte, is the ebullient architect Troyte Griffith; anonymous but probably conceals Lady Mary Lygon, Variation 8, W.N., is the graceful Winifred Norbury; with a reference to Mendelssohn’s Overture Calm Sea The young British pianist Ashley Wass is recognised as one of the rising stars of his generation. Only the second ELGAR Variation 9, Nimrod, conceals the identity of Elgar’s and Prosperous Voyage hinting at her voyage to British pianist in twenty years to reach the finals of the Leeds Piano Competition (in 2000), he was the first British friend and publisher, Jaeger; Variation 10, Dorabella, is Australia, and the final Variation 14, E.D.U., is Elgar pianist ever to win the top prize at the World Piano Competition in 1997. He appeared in the Rising Stars series at Dora Penny, a country neighbour; Variation 11, G.R.S., himself, indicated by letters that spell out his wife’s pet the 2001 Ravinia Festival and his promise has been further acknowledged by the BBC, who selected him to be a Piano Music is the organist of Hereford Cathedral, Dr Sinclair, or, name for him, Edu. New Generations Artist over two seasons. Ashley Wass studied at Chethams Music School and won a scholarship more exactly, his dog Dan, heard falling into the river to the Royal Academy of Music to study with Christopher Elton and Hamish Milne. -

The Dream of Gerontius

in a side-by-side concert with musicians from The Bard College Conservatory Orchestra THE DREAM OF GERONTIUS apr 8/9 2017 The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College Enjoying in a side-by-side concert with musicians from The Bard College Conservatory Orchestra The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College the concert? Sosnoff Theater Saturday, April 8, 2017 at 8 PM Help keep the Sunday, April 9, 2017 at 2 PM music going! Performances #52 & #53: Season 2, Concerts 23 & 24 Leon Botstein, conductor This new generation of musicians is creating and presenting music education programs in libraries, schools, and Edward Elgar The Dream of Gerontius, Op. 38 (1900) community centers in the Hudson Valley. (1857–1934) Part I Intermission Support their work Part II by making a gift of any size. Gerontius: Jonathan Tetelman, tenor The Angel: Sara Murphy, mezzo-soprano The Priest / The Angel of the Agony: Christopher Burchett, baritone Bard College Chamber Singers James Bagwell, director Cappella Festiva Chamber Choir Christine Howlett, artistic director Vassar College Choir or Christine Howlett, conductor TEXT VISIT Text from The Dream of Gerontius by John Henry Cardinal Newman TON TO 41444 THEORCHESTRANOW. ORG/SUPPORT This concert is supported in part by The Elgar Society The concert will run approximately 2 hours and 10 minutes, including one 20-minute intermission. For more info on The TŌN Fund, see page 20. No beeping or buzzing, please! Silence all electronic devices. Photos and videos are encouraged, but only before and after the music.