Vol. 16, No. 1 March 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

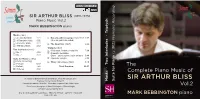

Sir Arthur Bliss (1891-1975) Céleste Series Piano Music Vol.2 MARK BEBBINGTON Piano Riptych

SOMMCD 0148 DDD Sir Arthur Bliss (1891-1975) Céleste Series Piano Music Vol.2 MArK BEBBiNGtON piano riptych t Masks (1924) · 1 A Comedy Mask 1:21 bl Das alte Jahr vergangen ist (1932) 2:57 2 A Romantic Mask 3:50 (The old year has ended) Première Recording 3 A Sinister Mask 2:22 bm The Rout Trot (1927) 2:42 4 A Military Mask 2:53 Triptych (1970) Two Interludes (1925) .1912) bn Meditation: Andante tranquillo 7:08 5 c No. 1 4:09 bo ( Dramatic Recitative: 6 nterludes No. 2 3:23 Grave – poco a poco molto animato 5:48 i bp Suite for Piano (c.1912) Capriccio: allegro 5:09 Première Recording bq wo 7 ‛Bliss’ (One-Step) (1923) 3:15 Prelude 5:47 t The 8 Ballade 7:48 Total Duration: 62:11 · 9 Scherzo 3:32 Complete Piano Music of Recorded at Symphony Hall, Birmingham, 3rd & 4th January 2011 Sir Arthur Bliss Steinway Concert Grand Model 'D' Masks Suite for Piano Recording Producer: Siva Oke Recording Engineer: Paul Arden-Taylor Vol.2 Front Cover photograph of Mark Bebbington: © Rama Knight Design & Layout: Andrew Giles © & 2015 SOMM RECORDINGS · THAMES DITTON · SURREY · ENGLAND MArK BEBBiNGtON piano Made in the EU THE SOLO PIANO MUSIC OF SIR ARTHUR BLISS Vol. 2 Anyone coming new to Bliss’s piano music via these publications might be forgiven for For anyone who has investigated the piano music of Arthur Bliss, the most puzzling thinking that the composer’s contribution to the repertoire was of little significance, aspect is surely that, as a body of work, it remains so little known. -

≥ Elgar Sea Pictures Polonia Pomp and Circumstance Marches 1–5 Sir Mark Elder Alice Coote Sir Edward Elgar (1857–1934) Sea Pictures, Op.37 1

≥ ELGAR SEA PICTURES POLONIA POMP AND CIRCUMSTANCE MARCHES 1–5 SIR MARK ELDER ALICE COOTE SIR EDWARD ELGAR (1857–1934) SEA PICTURES, OP.37 1. Sea Slumber-Song (Roden Noel) .......................................................... 5.15 2. In Haven (C. Alice Elgar) ........................................................................... 1.42 3. Sabbath Morning at Sea (Mrs Browning) ........................................ 5.47 4. Where Corals Lie (Dr Richard Garnett) ............................................. 3.57 5. The Swimmer (Adam Lindsay Gordon) .............................................5.52 ALICE COOTE MEZZO SOPRANO 6. POLONIA, OP.76 ......................................................................................13.16 POMP AND CIRCUMSTANCE MARCHES, OP.39 7. No.1 in D major .............................................................................................. 6.14 8. No.2 in A minor .............................................................................................. 5.14 9. No.3 in C minor ..............................................................................................5.49 10. No.4 in G major ..............................................................................................4.52 11. No.5 in C major .............................................................................................. 6.15 TOTAL TIMING .....................................................................................................64.58 ≥ MUSIC DIRECTOR SIR MARK ELDER CBE LEADER LYN FLETCHER WWW.HALLE.CO.UK -

String Quartet in E Minor, Op 83

String Quartet in E minor, op 83 A quartet in three movements for two violins, viola and cello: 1 - Allegro moderato; 2 - Piacevole (poco andante); 3 - Allegro molto. Approximate Length: 30 minutes First Performance: Date: 21 May 1919 Venue: Wigmore Hall, London Performed by: Albert Sammons, W H Reed - violins; Raymond Jeremy - viola; Felix Salmond - cello Dedicated to: The Brodsky Quartet Elgar composed two part-quartets in 1878 and a complete one in 1887 but these were set aside and/or destroyed. Years later, the violinist Adolf Brodsky had been urging Elgar to compose a string quartet since 1900 when, as leader of the Hallé Orchestra, he performed several of Elgar's works. Consequently, Elgar first set about composing a String Quartet in 1907 after enjoying a concert in Malvern by the Brodsky Quartet. However, he put it aside when he embarked with determination on his long-delayed First Symphony. It appears that the composer subsequently used themes intended for this earlier quartet in other works, including the symphony. When he eventually returned to the genre, it was to compose an entirely fresh work. It was after enjoying an evening of chamber music in London with Billy Reed’s quartet, just before entering hospital for a tonsillitis operation, that Elgar decided on writing the quartet, and he began it whilst convalescing, completing the first movement by the end of March 1918. He composed that first movement at his home, Severn House, in Hampstead, depressed by the war news and debilitated from his operation. By May, he could move to the peaceful surroundings of Brinkwells, the country cottage that Lady Elgar had found for them in the depth of the Sussex countryside. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Chanson De Nuit Op 15 for Guitar Duo Sheet Music

Chanson De Nuit Op 15 For Guitar Duo Sheet Music Download chanson de nuit op 15 for guitar duo sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 2 pages partial preview of chanson de nuit op 15 for guitar duo sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 2817 times and last read at 2021-10-01 09:55:44. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of chanson de nuit op 15 for guitar duo you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Classical Guitar Ensemble: Mixed Level: Advanced [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Chanson De Nuit And Chanson De Matin Op 15 For Guitar Duo Chanson De Nuit And Chanson De Matin Op 15 For Guitar Duo sheet music has been read 3664 times. Chanson de nuit and chanson de matin op 15 for guitar duo arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-10-01 10:42:32. [ Read More ] Chanson De Nuit And Chanson De Matin Op 15 For Cello And Guitar Chanson De Nuit And Chanson De Matin Op 15 For Cello And Guitar sheet music has been read 3488 times. Chanson de nuit and chanson de matin op 15 for cello and guitar arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 5 preview and last read at 2021-10-01 09:55:06. [ Read More ] Chanson De Nuit And Chanson De Matin Op 15 For Flute And Guitar Chanson De Nuit And Chanson De Matin Op 15 For Flute And Guitar sheet music has been read 6579 times. -

Journal September 1984

The Elgar Society JOURNAL ^■m Z 1 % 1 ?■ • 'y. W ■■ ■ '4 September 1984 Contents Page Editorial 3 News Items and Announcements 5 Articles: Further Notes on Severn House 7 Elgar and the Toronto Symphony 9 Elgar and Hardy 13 International Report 16 AGM and Malvern Dinner 18 Eigar in Rutland 20 A Vice-President’s Tribute 21 Concert Diary 22 Book Reviews 24 Record Reviews 29 Branch Reports 30 Letters 33 Subscription Detaiis 36 The editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views The cover portrait is reproduced by kind permission of National Portrait Gallery This issue of ‘The Elgar Society Journal’ is computer-typeset. The computer programs were written by a committee member, Michael Rostron, and the processing was carried out on Hutton -t- Rostron’s PDPSe computer. The font used is Newton, composed on an APS5 photo-typesetter by Systemset - a division of Microgen Ltd. ELGAR SOCIETY JOURNAL ISSN 0143-121 2 r rhe Elgar Society Journal 01-440 2651 104 CRESCENT ROAD, NEW BARNET. HERTS. EDITORIAL September 1984 .Vol.3.no.6 By the time these words appear the year 1984 will be three parts gone, and most of the musical events which took so long to plan will be pleasant memories. In the Autumn months there are still concerts and lectures to attend, but it must be admitted there is a sense of ‘winding down’. However, the joint meeting with the Delius Society in October is something to be welcomed, and we hope it may be the beginning of an association with other musical societies. -

'The Crown of India' Masque: Reassessing Elgar and The

Mughals, Music, and “The Crown of India” Masque: Reassessing Elgar and the Raj published in South Asian Review 31.1 (November 2010): 13-36. Abstract Edward Elgar’s 1912 masque, “The Crown of India,” was written specifically for the music hall in celebration of the crowning of King George V and Queen Mary at the Delhi Durbar in 1911. This work has been addressed by musical and postcolonial scholars, and has been appropriated by two factions: those who wish to claim Elgar as an unrepentant imperialist, and see that manifested in this work, and those who wish to see him as a beacon for anti-imperialism, who see evidence of this in the cuts that he made to the libretto, written by Henry Hamilton. What has been lacking in this discourse is a vehicle to address those cuts from a literary perspective, citing actual support from the two versions of the libretto (with and without cuts). This paper will reassess the masque in light of these libretti, and offer a new assessment of Elgar’s imperial tendencies at that point in time, and the imperialism of the Raj. Article The Great Delhi Durbar of December 12, 1911, the third, final, and most spectacular of all the Imperial Durbars, was, according to all accounts, a spectacle of unheard-of opulence and extravagance. In it, King George V and Queen Mary were presented as Emperor and Empress of India, and, in their coronation robes, accepted presents from and the fealty of over 200 Indian princes. Amidst all the pomp, some matters of great import were decided at the Durbar. -

The Elgar Sketch-Books

THE ELGAR SKETCH-BOOKS PAMELA WILLETTS A MAJOR gift from Mrs H. S. Wohlfeld of sketch-books and other manuscripts of Sir Edward Elgar was received by the British Library in 1984. The sketch-books consist of five early books dating from 1878 to 1882, a small book from the late 1880s, a series of eight volumes made to Elgar's instructions in 1901, and two later books commenced in Italy in 1909.^ The collection is now numbered Add. MSS. 63146-63166 (see Appendix). The five early sketch-books are oblong books in brown paper covers. They were apparently home-made from double sheets of music-paper, probably obtained from the stock of the Elgar shop at 10 High Street, Worcester. The paper was sewn together by whatever means was at hand; volume III is held together by a gut violin string. The covers were made by the expedient of sticking brown paper of varying shades and textures to the first and last leaves of music-paper and over the spine. Book V is of slightly smaller oblong format and the sides of the music sheets in this volume have been inexpertly trimmed. The volumes bear Elgar's numbering T to 'V on the covers, his signature, and a date, perhaps that ofthe first entry in the volumes. The respective dates are: 21 May 1878(1), 13 August 1878 (II), I October 1878 (III), 7 April 1879 (IV), and i September 1881 (V). Elgar was not quite twenty-one when the first of these books was dated. Earlier music manuscripts from his hand have survived but the particular interest of these early sketch- books is in their intimate connection with the round of Elgar's musical activities, amateur and professional, at a formative stage in his career. -

Swan Lake Takes out the Classic 100: Dance Countdown

10 JUNE 2018 – EMBARGOED UNTIL 19:01 AEST-- Swan Lake takes out the Classic 100: Dance Countdown Swan Lake has been named Australia’s favourite classical dance music in ABC Classic FM’s Classic 100 Countdown. Australia’s favourite classical music event has celebrated the brilliant diversity, vivid colour and irresistible impulse of dance, by counting down the music that makes its audiences move. Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, one of the world’s most beloved ballets, tells the story of Odette, a princess transformed into a swan by the curse of an evil sorcerer. Australia’s passionate community of music lovers voted in their thousands in the annual campaign by ABC Classic FM, our only national classical music station. Nearly 2000 works were reduced by public voting to the final 100 broadcast this weekend. More than 50% of the performers featured in this flagship event are Australian, exemplifying the ABC’s crucial role in nurturing local talent. ABC Classic FM is dedicated to investing in high-quality and distinctive Australian music and performance, free for all Australians. ABC Classic FM has collaborated with The Australian Ballet to produce three films specifically for the Countdown. Emerging choreographers Alice Topp, Richard House and Ella Havelka created striking new responses to the top three featured works: Swan Lake, The Nutcracker Suite, and Romeo and Juliet. Why Dance, a 3 x 20 minute feature series from the ABC’s Dr Ann Jones, has launched on air on ABC Classic FM, online and on the ABC listen app to mark this year’s theme. In association with The Australian Ballet, Sydney Dance Company and Bangarra Dance Theatre, Ann explores female choreographers in the male- dominated world of ballet, the importance of dance in Indigenous culture, and the healing role of dance in the lives of some everyday Australians. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

Scratch Pad 77 March 2011 TARAL WAYNE :: NIALL Mcgrath & TIM TRAIN :: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) :: BRUCE GILLESPIE :: ABC CLASSICS Top 100 Scratch Pad 77 March 2011

Scratch Pad 77 March 2011 TARAL WAYNE :: NIALL McGRATH & TIM TRAIN :: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) :: BRUCE GILLESPIE :: ABC CLASSICS Top 100 Scratch Pad 77 March 2011 Based on the non-mailing comments section of *brg* 67 and 68, a fanzine for ANZAPA (Australia and New Zealand Amateur Publishing Association) written and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard St, Greensborough VIC 3088. Phone: (03) 9435 7786. Email: [email protected]. Member fwa. Website: GillespieCochrane.com.au Contents 3 Unsolved mysteries of the hereafter — by Taral Wayne 6 The brand new Scratch Pad poetry spot — by Niall McGrath and Tim Train 9 Ditmar’s best and favourite films of 2010 — by Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) 15 Shining shores: Bruce Gillespie’s favourites 2010 — by Bruce Gillespie 36 ABC Classic 100 ten years on: 2010 — introduced by Bruce Gillespie Cover graphic — ‘Evening Phenomenon’ by Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Cartoon p. 3: ‘Unsolved mysteries’ — by Taral Wayne 2 Unsolved mysteries of the hereafter by Taral Wayne I think some scholar, or someone who wanted to be mistaken for one, claimed that the translation from the Koran was wrong, and it wasn’t ‘seventy virgins’, but something like ‘seventy figs’, that a good Muslim could expect in Paradise, and that it only meant the blessed would be in the midst of plenty. I’m not sure I buy that. It was only 1500 years ago, and I don’t think Arabic then was so different from modern Arabic that millions of Arab Muslims make such an elementary mistake. But who knows ... maybe Allah really only did mean that the nearly arrived would be greeted with a plate of figs .. -

Music Written for Piano and Violin

Music written for piano and violin: Title Year Approx. Length Allegretto on GEDGE 1885 4 mins 30 secs Bizarrerie 1889 2 mins 30 secs La Capricieuse 1891 4 mins 30 secs Gavotte 1885 4 mins 30 secs Une Idylle 1884 3 mins 30 secs May Song 1901 3 mins 45 secs Offertoire 1902 4 mins 30 secs Pastourelle 1883 3 mins 00 secs Reminiscences 1877 3 mins 00 secs Romance 1878 5 mins 30 secs Virelai 1883 3 mins 00 secs Publishers survive by providing the public with works they wish to buy. And a struggling composer, if he wishes his music to be published and therefore reach a wider audience, must write what a publisher believes he can sell. Only having established a reputation can a composer write larger scale works in a form of his own choosing with any realistic expectation of having them performed. During the latter half of the nineteenth century, the stock-in-trade for most publishers was the sale of sheet music of short salon pieces for home performance. It was a form that was eventually to bring Elgar considerably enhanced recognition and a degree of financial success with the publication for solo piano of Salut d'Amour in 1888 and of three hugely popular works first published in arrangements for piano and violin - Mot d'Amour (1889), Chanson de Nuit (1897) and Chanson de Matin (1899). Elgar composed short pieces for solo piano sporadically throughout his life. But, apart from the two Chansons, May Song (1901) and Offertoire (1902), an arrangement of Sospiri and, of course, the Violin Sonata, all of Elgar's works for piano and violin were composed between 1877, the dawning of his ambitions to become a serious composer, and 1891, the year after his first significant orchestral success withFroissart.