The Insecure City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SECTARIAN MOVEMENT in LEBANON TRANSFORMING from STREET PROTESTS TOWARDS a FULL- FLEDGED POLITICAL MOVEMENT Wetenschappelijke Verhandeling Aantal Woorden: 25.981

THE EMERGENCE OF THE NON- SECTARIAN MOVEMENT IN LEBANON TRANSFORMING FROM STREET PROTESTS TOWARDS A FULL- FLEDGED POLITICAL MOVEMENT Wetenschappelijke verhandeling Aantal woorden: 25.981 Jesse Waterschoot Stamnummer: 01306668 Promotor: Prof. dr. Christopher Parker Masterproef voorgelegd voor het behalen van de graad master in de richting Politieke Wetenschappen afstudeerrichting Internationale Politiek Academiejaar: 2017-2018 Acknowledgements I would like to thank all the individuals with whom I have discussed this topic. Through its specificity, online information was sometimes hard to find, so I would like to thank every individual in Lebanon that shared information with me. I extend my sincere gratitude to my colleagues at Heinrich Böll Stichtung Beirut, who supported me in my project on the Lebanese elections and shared their insights with me. Without their assistance and contacts in Beirut’s political scene, finishing this dissertation would have been much harder. Whenever I had any question about a Lebanese party, organisation or politician they were happy to provide information. A special acknowledgment must be given to my promotor, Christopher Parker. Through your guidance and advice on this specific topic and support for my internship plans, I was able to complete this dissertation. 3 Abstract Deze Master thesis behandelt de opkomst van de Libanese niet-sektarische beweging. Libanon kent een confessioneel systeem, waarbij de staat en samenleving georganiseerd is op basis van religie. Deze bestuursvorm resulteerde in een politiek-religieuze elite die overheidsdiensten monopoliseerde en herstructureerde om diensten te voorzien aan hun religieuze achterban, in ruil voor hun loyaliteit. Na de burgeroorlog werd dit confessioneel systeem aangepast, maar niet fundamenteel gewijzigd. -

UNIT-III 1. Middle East Countries 2. Central and Middle Asia 3. China 4

WORLD TOURISM DESTINATIONS UNIT-III 1. Middle East Countries 2. Central and Middle Asia 3. China 4. SAARC Countries A S I A N C O N T I N E N T 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 2 Countries in ASIAN Continent : 48+03+01 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 3 WEST ASIA CENTRAL ASIA SOUTH ASIA 12/11/2020NORTH ASIA Saravanan_doc_WorldEAST ASIA Tourism_PPT SOUTH EAST ASIA4 WEST ASIA 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 5 WEST ASIAN COUNTRIES • Armenia • Lebanon • Azerbaijan • Oman • Bahrain • Palestine • Cyprus • Qatar • Georgia • Saudi Arabia • Iraq • Syria • Iran • Turkey • Israel • United Arab Emirates • Jordan • Yemen • Kuwait 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 6 Armenia 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 7 Azerbaijan 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 8 Bahrain 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 9 Cyprus 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 10 Georgia 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 11 Iraq 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 12 Iran 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 13 Israel 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 14 Jordan 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 15 Kuwait 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 16 Lebanon 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 17 Oman 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 18 Palestine 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 19 Qatar 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 20 Saudi Arabia 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 21 Syria 12/11/2020 Saravanan_doc_World Tourism_PPT 22 Turkey -

Lebanon: Managing the Gathering Storm

LEBANON: MANAGING THE GATHERING STORM Middle East Report N°48 – 5 December 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. A SYSTEM BETWEEN OLD AND NEW.................................................................. 1 A. SETTING THE STAGE: THE ELECTORAL CONTEST..................................................................1 B. THE MEHLIS EFFECT.............................................................................................................5 II. SECTARIANISM AND INTERNATIONALISATION ............................................. 8 A. FROM SYRIAN TUTELAGE TO WESTERN UMBRELLA?............................................................8 B. SHIFTING ALLIANCES..........................................................................................................12 III. THE HIZBOLLAH QUESTION ................................................................................ 16 A. “A NEW PHASE OF CONFRONTATION” ................................................................................17 B. HIZBOLLAH AS THE SHIITE GUARDIAN?..............................................................................19 C. THE PARTY OF GOD TURNS PARTY OF GOVERNMENT.........................................................20 IV. CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................. 22 A. A BROAD INTERNATIONAL COALITION FOR A NARROW AGENDA .......................................22 B. A LEBANESE COURT ON FOREIGN -

J08-4692 from Akkar to Amel.Indd

Places, Products and Producers from Lebanon Printed by: To all the small producers of the world This book took one and a half years to complete. Many people were instrumental in shaping the final product. Andrea Tamburini was the dynamo who kept spirits high and always provided timely encourage- ment. Without him, this book could not have seen the light. Walid Ataya, the president of Slow Food Beirut, and the Slow Food Beirut group: Johnny Farah, Nelly Chemaly, Barbara Masaad and Youmna Ziadeh also provided their friendly support. Myriam Abou Haidar worked in the shadow, but without her logistical assistance, this work could not have been completed on time. The Slow Food team, espe- cially Piero Sardo, Serena Milano and Simone Beccaria from the Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity offered guidance in the develop- ment of the inventory, and back-up for the publication project. Deborah Chay meticulously and repeatedly edited the texts, for which she shares authorship. Great thanks are also due to Muna Khalidi who did the final round of editing and checked the text for inconsistencies. Dr. Imad Toufaily must also be acknowledged for his careful technical review. Waleed Saab, the gifted young designer, worked with us every step of the process. His skills, patience and creativity clearly appear throughout the book. The talented Cynthia Gharios magically created the map. We owe her our deepest appreciation. Rouba Ziadeh kindly provided the GIS maps which helped us understand the landscape- food relationships. Finally, we are indebted to all the producers and their families for their unlimited patience and their kind hospitality. -

MOST VULNERABLE LOCALITIES in LEBANON Coordination March 2015 Lebanon

Inter-Agency MOST VULNERABLE LOCALITIES IN LEBANON Coordination March 2015 Lebanon Calculation of the Most Vulnerable Localities is based on 251 Most Vulnerable Cadastres the following datasets: 87% Refugees 67% Deprived Lebanese 1 - Multi-Deprivation Index (MDI) The MDI is a composite index, based on deprivation level scoring of households in five critical dimensions: i - Access to Health services; Qleiaat Aakkar Kouachra ii - Income levels; Tall Meaayan Tall Kiri Khirbet Daoud Aakkar iii - Access to Education services; Tall Aabbas El-Gharbi Biret Aakkar Minyara Aakkar El-Aatiqa Halba iv - Access to Water and Sanitation services; Dayret Nahr El-Kabir Chir Hmairine ! v - Housing conditions; Cheikh Taba Machta Hammoud Deir Dalloum Khreibet Ej-Jindi ! Aamayer Qoubber Chamra ! ! MDI is from CAS, UNDP and MoSA Living Conditions and House- ! Mazraat En-Nahriyé Ouadi El-Jamous ! ! ! ! ! hold Budget Survey conducted in 2004. Bebnine ! Akkar Mhammaret ! ! ! ! Zouq Bhannine ! Aandqet ! ! ! Machha 2 - Lebanese population dataset Deir Aammar Minie ! ! Mazareaa Jabal Akroum ! Beddaoui ! ! Tikrit Qbaiyat Aakkar ! Rahbé Mejdlaiya Zgharta ! Lebanese population data is based on CDR 2002 Trablous Ez-Zeitoun berqayel ! Fnaydeq ! Jdeidet El-Qaitaa Hrar ! Michmich Aakkar ! ! Miriata Hermel Mina Jardin ! Qaa Baalbek Trablous jardins Kfar Habou Bakhaaoun ! Zgharta Aassoun ! Ras Masqa ! Izal Sir Ed-Danniyé The refugee population includes all registered Syrian refugees, PRL Qalamoun Deddé Enfé ! and PRS. Syrian refugee data is based on UNHCR registration Miziara -

Patience and Comparative Development*

Patience and Comparative Development* Thomas Dohmen Benjamin Enke Armin Falk David Huffman Uwe Sunde May 29, 2018 Abstract This paper studies the role of heterogeneity in patience for comparative devel- opment. The empirical analysis is based on a simple OLG model in which patience drives the accumulation of physical capital, human capital, productivity improve- ments, and hence income. Based on a globally representative dataset on patience in 76 countries, we study the implications of the model through a combination of reduced-form estimations and simulations. In the data, patience is strongly corre- lated with income levels, income growth, and the accumulation of physical capital, human capital, and productivity. These relationships hold across countries, sub- national regions, and individuals. In the reduced-form analyses, the quantitative magnitude of the relationship between patience and income strongly increases in the level of aggregation. A simple parameterized version of the model generates comparable aggregation effects as a result of production complementarities and equilibrium effects, and illustrates that variation in preference endowments can account for a considerable part of the observed variation in per capita income. JEL classification: D03, D90, O10, O30, O40. Keywords: Patience; comparative development; factor accumulation. *Armin Falk acknowledges financial support from the European Research Council through ERC # 209214. Dohmen, Falk: University of Bonn, Department of Economics; [email protected], [email protected]. Enke: Harvard University, Department of Economics; [email protected]. Huffman: University of Pittsburgh, Department of Economics; huff[email protected]. Sunde: University of Munich, Department of Economics; [email protected]. 1 Introduction A long stream of research in development accounting has documented that both pro- duction factors and productivity play an important role in explaining cross-country income differences (Hall and Jones, 1999; Caselli, 2005; Hsieh and Klenow, 2010). -

Avant-Propos De L'édition Numérique

Avant-propos de l’édition numérique Libanavenir entre dans une deuxième étape À mes compatriotes libanais, prenons notre destin en main et agissons * * * Les sept ans de vie du site libanavenir ont permis de produire les Cahiers de Liban Avenir, imprimés à l’automne 2018. Ces cahiers sont désormais publiés sur Internet. Vous pouvez y avoir accès librement et gratuitement sur le site (www.libanavenir.wordpress.com) en lecture et en téléchargement. Notre équipe est convaincue que vous y trouverez des idées pour contribuer à construire, à terme, un État et créer une nation, grâce à votre implication personnelle. Un outil de travail et de réflexion destiné à cette jeunesse qui aspire à entrer en politique, et même s’y prépare, ainsi que pour les plus anciens qui cherchent des voies pour retrouver l’espoir. Les sujets de ces Cahiers sont multiples : politiques, écologiques, historiques, de réflexion. Ils sont listés par thème dans la table des matières et ont pour point commun d’aborder sous divers angles, les problèmes que connaît le Liban. Analysés, comparés, argumentés, ces éléments de réflexion ont vocation à aider ceux qui souhaitent s’engager à regarder nos réalités en face, et à trouver des solutions adaptées à notre pays. Avec cette matière, nous souhaitons favoriser la proximité et la solidarité et créer du lien afin de rompre ce cercle vicieux de méfiance vis-à-vis de l’autre perçu comme une menace, d’où un repli sur la famille, la tribu, la communauté, et un rejet de l’autre. Un cercle vicieux entretenu au sein même du pays du fait de notre système politique confessionnel qui joue sur nos communautés et nous divise, sans compter les vents contraires lorsqu’ils soufflent de l’extérieur. -

National Action Plan for Human Rights in Lebanon

Copyright © 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the United Nations Development Programme. The analyses and policy recommendations in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Development Programme-Technical Support to the Lebanese Parliament. حقوق الطبع © 2013 جميع حقوق �لطبع حمفوظة. وﻻ يجوز ��شتن�ش�خ ّ�أي جزء من هذ� �ملن�شور �أو تخزينه يف نظ�م �إ�شرتج�ع �أو نقله ب�أي �شكل �أو ب�أية و�شيلة، �إلكرتونية ك�نت �أو �آلية، �أو ب�لن�شخ �ل�شوئي �أو ب�لت�شجيل، �أو ب�أية و�شيلة �أخرى، بدون �حل�شول على �إذن م�شبق من برن�مج �ﻻأمم �ملتحدة �ﻻإمن�ئي. ّ�إن �لتحليﻻت و�لتو�شي�ت ب�ش�أن �ل�شي��ش�ت �لو�ردة يف هذ� �لتقرير، ﻻ ّتعب ب�ل�شرورة عن �آر�ء برن�مج �ﻻأمم �ملتحدة �ﻻإمن�ئي- م�شروع تقدمي �لدعم �لتقني ملجل�س �لنو�ب �للبن�ين. Contents Foreword 5 Executive Summary 6 Chapter (1): General Framework 20 I. Methodology and Executive Measures for Follow Up and Implementation 20 II. Issues and general executive measures 25 General Executive Measures 32 Chapter (2): Sectoral Themes 33 1. The independence of the judiciary 33 2. The principles of investigation and detention 39 3. Torture and inhuman treatment 42 4. Forced disappearance 47 5. Prisons and detention facilities 51 6. Death penalty 61 7. Freedom of expression, opinion and the media 65 8. -

Digital Edition

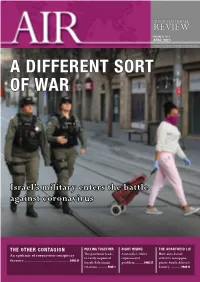

AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL REVIEW VOLUME 45 No. 4 APRIL 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL & JEWISH AFFAIRS COUNCIL A DIFFERENT SORT OF WAR Israel’s military enters the battle against coronavirus THE OTHER CONTAGION PULLING TOGETHER RIGHT RISING THE APARTHEID LIE An epidemic of coronavirus conspiracy The pandemic leads Australia’s white How anti-Israel to vastly improved supremacist activists misappro- theories ............................................... PAGE 21 Israeli-Palestinian problem ........PAGE 27 priate South Africa’s relations .......... PAGE 7 history ........... PAGE 31 WITH COMPLIMENTS NAME OF SECTION L1 26 BEATTY AVENUE ARMADALE VIC 3143 TEL: (03) 9661 8250 FAX: (03) 9661 8257 WITH COMPLIMENTS 2 AIR – April 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL VOLUME 45 No. 4 REVIEW APRIL 2020 EDITOR’S NOTE NAME OF SECTION his AIR edition focuses on the Israeli response to the extraordinary global coronavirus ON THE COVER Tpandemic – with a view to what other nations, such as Australia, can learn from the Israeli Border Police patrol Israeli experience. the streets of Jerusalem, 25 The cover story is a detailed look, by security journalist Alex Fishman, at how the IDF March 2020. Israeli authori- has been mobilised to play a part in Israel’s COVID-19 response – even while preparing ties have tightened citizens’ to meet external threats as well. In addition, Amotz Asa-El provides both a timeline of movement restrictions to Israeli measures to meet the coronavirus crisis, and a look at how Israel’s ongoing politi- prevent the spread of the coronavirus that causes the cal standoff has continued despite it. Plus, military reporter Anna Ahronheim looks at the COVID-19 disease. (Photo: Abir Sultan/AAP) cooperation the emergency has sparked between Israel and the Palestinians. -

The Lebanese Parliamentary Elections of 2018: Much Ado About Nothing?

Peter Nassif FOKUS | 4/2018 The Lebanese Parliamentary Elections of 2018: Much Ado about Nothing? On 6 May 2018, Lebanon went to the polls humanitarian support for Syrian refugees Political and Security Challenges to elect a new parliament for the first time as well as political support for neighboring in nine years. These elections stand out host countries.3 More important was the The parliament’s elections were postponed for the largest reform in voting laws in CEDRE4 donor conference that was held in 2013 and 2014 because of security Lebanese history, the influence of regional in Paris on 6 April, where 11 billion USD con cerns. During the time, the Syrian War tensions, but also a civil society challen- in credits and grants were pledged to Le- was raging in the Lebanese-Syrian border ging the old guard. After much anticipa- banon during election season – a country region, while the rise of ISIS and frequent tion, the general elections changed less with a gross public debt of almost 80 billi- car bombings in Hezbollah’s southern the political landscape than many people on USD5 and the fifth-highest debt-to-GDP Beirut neighborhoods led to a general had hoped. The results demonstrated that ratio worldwide.6 sense of insecurity. The Syrian government Lebanese voters and political parties are was losing ground and the Lebanese Shiite still far away from running and voting on A Peculiar Political System Hezbollah militia had joined the conflict in policy-based solutions to tackle the socio- 2012 to fight alongside the regime. It took economic challenges facing the country. -

Lebanese Expats Fearful As GCC Nations Expel Dozens

SUBSCRIPTION SATURDAY, APRIL 9, 2016 RAJAB 2, 1437 AH No: 16839 Kuwait mourns British brands eye Warriors clinch luminary stage growing Muslim home-court director 2Al-Shatti consumer25 market advantage48 Lebanese expats fearful as GCC nations expel dozens Min 19º 150 Fils 100 expelled from Bahrain, Kuwait, UAE in 2 months Max 36º DUBAI: Ahmed, a Lebanese worker living in the United Arab Emirates, closed down his Facebook page and started to shun some of his compatriots. His intention was to sever all links to people associated with Lebanon’s Hezbollah after Gulf Arab states classified the Shiite Muslim organiza- tion as a terrorist group. Ahmed, a medical worker in his early 50s who declined to give his full name, is not alone. Anxiety and apprehension are unsettling many of the up to 400,000 Lebanese workers living in the Gulf after last month’s announcement by the Gulf Cooperation Council - Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman and Qatar. The rich states, where Lebanese have worked for generations, some achieving wealth and influ- ence, have threatened to imprison and expel anyone linked to the Iranian-allied group that fights in support of President Bashar Al-Assad in Syria’s civil war. The GCC move on Hezbollah is part of a struggle pitting Sunni Saudi Arabia against Shiite regional heavyweight Iran. The rivals back different factions in Lebanon where Hezbollah wields enormous political influence as well as MANAMA: (From left) Kuwait Foreign Minister Sheikh Sabah Al-Khaled Al-Sabah, Qatar Foreign Minister Mohammed bin having a powerful military wing. -

Here to Play Back Faithfully in Any Theatre

399644_CAS_QuarterlyMagazineAwards_Ad.indd 1 HBO® CONGRATULATES OUR 49TH CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARDS WINNER Jamie Ledner Brian Riordan,CAS ©2013 HomeBoxOffice,Inc. Allrightsreserved.HBO FOR YOURRECOGNITION THANK YOU,CASMEMBERS, FAME INDUCTIONCEREMONY THE 2012ROCK&ROLLHALLOF SERIES ORSPECIALS VARIETY ORMUSIC TELEVISION NON-FICTION, ® andrelatedchannelsservice marksarethepropertyofHomeBoxOffice,Inc. 4/22/13 5:41 PM MORE POWERFUL STORYTELLING BRINGS YOUR VISION TO LIFE Hear what industry professionals say about Dolby® Atmos™. EXPANDS THE ARTISTIC PALETTE Place and move sound anywhere to play back faithfully in any theatre. “I strive to make movies that allow the audience to participate in the events onscreen, rather than just watch them unfold. Wonderful technology is now available to support this goal: high frame rates, 3D, and now the stunning Dolby Atmos system. Dolby has always been at the cutting edge of providing cinema audiences with the ultimate sound experience, and they have now surpassed them- selves. Dolby Atmos provides the completely immersive sound experience that filmmakers like myself have long dreamed about.” —Peter Jackson, Co-Writer, Director, and Producer The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey SIMPLIFIES AUDIO POSTPRODUCTION Automatically generate 5.1, 7.1, and other delivery formats from the Dolby Atmos mix. “We needed a workflow that matched what we use already for Dolby Atmos to work for The Hobbit in the timeframe we had. Dolby had really great ideas for integration and developed the tools we needed for a bulletproof process.” —Gilbert Lake, Dolby Atmos Rerecording Mixer The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey See the full list of Dolby Atmos titles at dolby.com/atmosmovies. Dolby and the double-D symbol are registered trademarks of Dolby Laboratories.