Verdi's Don Carlo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repetiteurs Masterclasses

www.georgsoltiaccademia.org Repetiteurs Masterclasses The Georg Solti Accademia announces LWV¿IWK6ROWL3HUHWWL5pSpWLWHXUV0DVWHUFODVVHV in Barcelona, 2 | 10 April 2013 The Georg Solti Accademia Répétiteur’s Masterclasses are unique in the music world, and have become the go-to intensive course for aspiring répétiteurs internationally. Featured last year on BBC 2’s series Maestro at the Opera, the course offers an immersion in preparing singers for operatic performance, with an incomparable faculty of teachers including Sir Richard Bonynge, Pamela Bullock, Jonathan Papp and Audrey Hyland. This year the President of the Nando and Elsa Peretti Foundations, Ms Elsa Peretti (the pre-eminent designer for Tiffany), has made it possible for the course to be run in Elsa’s elective city of Barcelona, in collaboration with the Theatre Akademia, where WKHUpSpWLWHXU¶V¿QDOFRQFHUWZLOOWDNHSODFHRQ$SULODW Six outstanding young pianists, from $XVWUDOLD)UDQFH*UHHFH6SDLQDQGWKH8., will gather in Barcelona in April with six talented singers, all alumni of the Georg Solti Accademia’s Bel Canto course, to focus on this vital, but often hidden, craft. A répétiteur is the singer’s key ally in achieving their performance, and essential to any opera production. They are the ultimate multi-taskers of the opera world, and must be constantly alert to vocal performance, musicality, language, style and nuance, while bringing the whole orchestral score alive at the piano. No wonder so many of them go on to become great opera conductors – Georg Solti, Riccardo Muti, Valery Gergiev and Sir Antonio Pappano to name but four. This year the faculty includes the legendary 6LU5LFKDUG%RQ\QJH3DPHOD%XOORFN from Chicago Lyric Opera, -RQDWKDQ3DSS, Director of the Georg Solti Accademia di Bel Canto, $XGUH\+\ODQG from the Royal Academy of Music. -

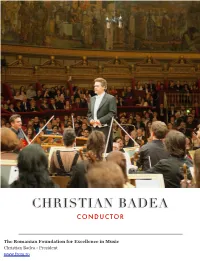

Christian Badea Conductor

CHRISTIAN BADEA CONDUCTOR The Romanian Foundation for Excellence in Music Christian Badea - President www.frem.ro Christian Badea has received exceptional acclaim throughout his career, which encompasses prestigious engagements in the foremost concert halls and opera houses of Europe, North America, Asia and Australia. Equally dividing his time between symphony and opera conducting, Christian Badea has appeared as a frequent guest in the major opera houses of the world. At the Metropolitan Opera in New York he conducted 167 performances in a wide variety of repertoire, including many of the MET international broadcasts. Among the opera houses where Christian Badea has guest conducted, are the Vienna State Opera, the Royal Opera House of Covent Garden in London, the Bayerische Staatsoper in München, the Staatsoper in Hamburg, the Deutsche Oper am Rhein in Düsseldorf, the Grand Théâtre de Genève, the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels, the Netherlands Opera in Amsterdam, the Royal Opera theaters in Copenhagen and Stockholm, the Oslo Opera, the Teatro Regio in Torino and the Teatro 1 Christian Badea at the Metropolitan Opera - New York Comunale in Bologna, the Opera National de Lyon and in North America - the opera companies of Houston, Dallas, Toronto, Montreal and Detroit. In recent years, Christian Badea has received great acclaim for his work at the Budapest State Opera (Tannhäuser, Der fliegende Holländer and Parsifal) , the Sydney Opera with new productions of Tosca, La bohème, Die tote Stadt, Otello and Falstaff, Oslo Opera – a new production of Tannhäuser, collaborating with stage director Stefan Herheim and Goteborg Opera – a new Don Carlo and Turandot. -

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

In Santa Cruz This Summer for Special Summer Encore Productions

Contact: Peter Koht (831) 420-5154 [email protected] Release Date: Immediate “THE MET: LIVE IN HD” IN SANTA CRUZ THIS SUMMER FOR SPECIAL SUMMER ENCORE PRODUCTIONS New York and Centennial, Colo. – July 1, 2010 – The Metropolitan Opera and NCM Fathom present a series of four encore performances from the historic archives of the Peabody Award- winning The Met: Live in HD series in select movie theaters nationwide, including the Cinema 9 in Downtown Santa Cruz. Since 2006, NCM Fathom and The Metropolitan Opera have partnered to bring classic operatic performances to movie screens across America live with The Met: Live in HD series. The first Live in HD event was seen in 56 theaters in December 2006. Fathom has since expanded its participating theater footprint which now reaches more than 500 movie theaters in the United States. We’re thrilled to see these world class performances offered right here in downtown Santa Cruz,” said councilmember Cynthia Mathews. “We know there’s a dedicated base of local opera fans and a strong regional audience for these broadcasts. Now, thanks to contemporary technology and a creative partnership, the Metropolitan Opera performances will become a valuable addition to our already stellar lineup of visual and performing arts.” Tickets for The Met: Live in HD 2010 Summer Encores, shown in theaters on Wednesday evenings at 6:30 p.m. in all time zones and select Thursday matinees, are available at www.FathomEvents.com or by visiting the Regal Cinema’s box office. This summer’s series will feature: . Eugene Onegin – Wednesday, July 7 and Thursday, July 8– Soprano Renée Fleming and baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky star in Tchaikovsky’s lushly romantic masterpiece about mistimed love. -

Libretto Nabucco.Indd

Nabucco Musica di GIUSEPPE VERDI major partner main sponsor media partner Il Festival Verdi è realizzato anche grazie al sostegno e la collaborazione di Soci fondatori Consiglio di Amministrazione Presidente Sindaco di Parma Pietro Vignali Membri del Consiglio di Amministrazione Vincenzo Bernazzoli Paolo Cavalieri Alberto Chiesi Francesco Luisi Maurizio Marchetti Carlo Salvatori Sovrintendente Mauro Meli Direttore Musicale Yuri Temirkanov Segretario generale Gianfranco Carra Presidente del Collegio dei Revisori Giuseppe Ferrazza Revisori Nicola Bianchi Andrea Frattini Nabucco Dramma lirico in quattro parti su libretto di Temistocle Solera dal dramma Nabuchodonosor di Auguste Anicet-Bourgeois e Francis Cornu e dal ballo Nabucodonosor di Antonio Cortesi Musica di GIUSEPPE V ERDI Mesopotamia, Tavoletta con scrittura cuneiforme La trama dell’opera Parte prima - Gerusalemme All’interno del tempio di Gerusalemme, i Leviti e il popolo lamen- tano la triste sorte degli Ebrei, sconfitti dal re di Babilonia Nabucco, alle porte della città. Il gran pontefice Zaccaria rincuora la sua gente. In mano ebrea è tenuta come ostaggio la figlia di Nabucco, Fenena, la cui custodia Zaccaria affida a Ismaele, nipote del re di Gerusalemme. Questi, tuttavia, promette alla giovane di restituirle la libertà, perché un giorno a Babilonia egli stesso, prigioniero, era stato liberato da Fe- nena. I due innamorati stanno organizzando la fuga, quando giunge nel tempio Abigaille, supposta figlia di Nabucco, a comando di una schiera di Babilonesi. Anch’essa è innamorata di Ismaele e minaccia Fenena di riferire al padre che ella ha tentato di fuggire con uno stra- niero; infine si dichiara disposta a tacere a patto che Ismaele rinunci alla giovane. -

Zealot, Patriot, Spy? : Verdi's Marquis De Posa by Thomas Hampson

Zealot, Patriot, Spy? : Verdi’s Marquis de Posa by Thomas Hampson “There is nothing historical in this drama, so why not?” With these words rang a defense – at the same time a posture – Verdi adopted for the creation of Don Carlos. While the quote, written to his publisher G. Ricordi, pertains to the specific scene of the apparition of Charlemagne at the end of Act V, it is, nevertheless, hugely relevant when entertaining any reflections on Verdi’s Don Carlos. Already historically compromised by the great German poet-dramatist Friedrich Schiller, who, in fact, relied heavily on the occasionally embellished-interpreted history of Vischard de Saint Real, the story of Don Carlos presents a complex backdrop of political-religious (i.e. public) conflict by which the very personal dilemmas of love, jealousy, family, and faith are brought into sharp relief. Verdi’s genius in the articulation of the more-often-than-not catastrophic result of a personal passion pitted against various social, religious, or political contexts is well manifest in such works as Luisa Miller, I due Foscari, La Forza del Destino, Rigoletto, and, of course, La Traviata. However, with Don Carlos, the essentially metaphoric use of historical context as exposé of these conflicts accomplishes something remarkable in the theatre, and that is the recreation of the ambiguity of successive moments found in reality. There is no scene in the opera that ends in the same political or even personal context in which its starts. There is no formula for the tying together of scenes or even of acts – i.e. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series

Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series Frank Morelli, Bassoon Behind every Juilliard artist is all of Juilliard —including you. With hundreds of dance, drama, and music performances, Juilliard is a wonderful place. When you join one of our membership programs, you become a part of this singular and celebrated community. by Claudio Papapietro Photo of cellist Khari Joyner Photo by Claudio Papapietro Become a member for as little as $250 Join with a gift starting at $1,250 and and receive exclusive benefits, including enjoy VIP privileges, including • Advance access to tickets through • All Association benefits Member Presales • Concierge ticket service by telephone • 50% discount on ticket purchases and email • Invitations to special • Invitations to behind-the-scenes events members-only gatherings • Access to master classes, performance previews, and rehearsal observations (212) 799-5000, ext. 303 [email protected] juilliard.edu The Juilliard School presents Faculty Recital: Frank Morelli, Bassoon Jesse Brault, Conductor Jonathan Feldman, Piano Jacob Wellman, Bassoon Wednesday, January 17, 2018, 7:30pm Paul Hall Part of the Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series GIOACHINO From The Barber of Seville (1816) ROSSINI (arr. François-René Gebauer/Frank Morelli) (1792–1868) All’idea di quell metallo Numero quindici a mano manca Largo al factotum Frank Morelli and Jacob Wellman, Bassoons JOHANNES Sonata for Cello, No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 38 (1862–65) BRAHMS Allegro non troppo (1833–97) Allegro quasi menuetto-Trio Allegro Frank Morelli, Bassoon Jonathan Feldman, Piano Intermission Program continues Major funding for establishing Paul Recital Hall and for continuing access to its series of public programs has been granted by The Bay Foundation and the Josephine Bay Paul and C. -

Web Site Leads to GOP Complaint

Johnny Appleseed Linden students celebrated the American legend of Johnny Appleseed last week. Serving Linden, Roselle, Rahway and Elizabeth Page 3 LINDEN, N.J WWW.LOCALSOURCE.COM 75 CENTS VOL. 89 NO. 39 THURSDAY OCTOBER 5, 2006 Web site leads to GOP complaint By Kitty Wilder paid a total of $9 for two domain Kennedy said he was not aware ofthe site, Enforcement Commission said it is Managing Editor CAMPAIGN UPDATE names. The second domain name was adding, “It’s nothing I’m supporting.” not the commission’s policy to con RAHWAY — Local Republicans used to create a second Rahway He said Devine is not a consultant firm or deny complaints filed. have filed a complaint with the state Republicans for Kennedy Web site at for his campaign, but he is paid for Web sites have become common in alleging a Democratic campaign Lund. It did not contain a disclaimer. www.timeforchange2006.net. printing services. campaigning and are treated like other worker created a Web site intended to The site, which did not include a The address is similar to another Devine said he is a consultant for campaign literature, Davis said. They misrepresent their party. disclaimer, contained a similar address Bodine for Mayor address, www.time- Kennedy, adding, “I advise the Demo are required to include a disclaimer The complaint, filed Friday with to the homepage for the campaign rep forchange2006.com. cratic Party on strategic and tactical clarifying who paid for the site. the state Election Law Enforcement resenting the council candidates and Cassio said the similarity between measures to promote their candidates The commission follows a standard Commission, alleges the group Rah mayoral candidate Larry Bodine. -

Il Trovatore Was Made Stage Director Possible by a Generous Gift from Paula Williams the Annenberg Foundation

ilGIUSEPPE VERDItrovatore conductor Opera in four parts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Salvadore Cammarano and production Sir David McVicar Leone Emanuele Bardare, based on the play El Trovador by Antonio García Gutierrez set designer Charles Edwards Tuesday, September 29, 2015 costume designer 7:30–10:15 PM Brigitte Reiffenstuel lighting designed by Jennifer Tipton choreographer Leah Hausman The production of Il Trovatore was made stage director possible by a generous gift from Paula Williams The Annenberg Foundation The revival of this production is made possible by a gift of the Estate of Francine Berry general manager Peter Gelb music director James Levine A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the San Francisco principal conductor Fabio Luisi Opera Association 2015–16 SEASON The 639th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S il trovatore conductor Marco Armiliato in order of vocal appearance ferr ando Štefan Kocán ines Maria Zifchak leonor a Anna Netrebko count di luna Dmitri Hvorostovsky manrico Yonghoon Lee a zucena Dolora Zajick a gypsy This performance Edward Albert is being broadcast live on Metropolitan a messenger Opera Radio on David Lowe SiriusXM channel 74 and streamed at ruiz metopera.org. Raúl Melo Tuesday, September 29, 2015, 7:30–10:15PM KEN HOWARD/METROPOLITAN OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Verdi’s Il Trovatore Musical Preparation Yelena Kurdina, J. David Jackson, Liora Maurer, Jonathan C. Kelly, and Bryan Wagorn Assistant Stage Director Daniel Rigazzi Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Yelena Kurdina Assistant to the Costume Designer Anna Watkins Fight Director Thomas Schall Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted by Cardiff Theatrical Services and Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Lyric Opera of Chicago Costume Shop and Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Ms. -

Bellini's Norma

Bellini’s Norma - A discographical survey by Ralph Moore There are around 130 recordings of Norma in the catalogue of which only ten were made in the studio. The penultimate version of those was made as long as thirty-five years ago, then, after a long gap, Cecilia Bartoli made a new recording between 2011 and 2013 which is really hors concours for reasons which I elaborate in my review below. The comparative scarcity of studio accounts is partially explained by the difficulty of casting the eponymous role, which epitomises bel canto style yet also lends itself to verismo interpretation, requiring a vocalist of supreme ability and versatility. Its challenges have thus been essayed by the greatest sopranos in history, beginning with Giuditta Pasta, who created the role of Norma in 1831. Subsequent famous exponents include Maria Malibran, Jenny Lind and Lilli Lehmann in the nineteenth century, through to Claudia Muzio, Rosa Ponselle and Gina Cigna in the first part of the twentieth. Maria Callas, then Joan Sutherland, dominated the role post-war; both performed it frequently and each made two bench-mark studio recordings. Callas in particular is to this day identified with Norma alongside Tosca; she performed it on stage over eighty times and her interpretation casts a long shadow over. Artists since, such as Gencer, Caballé, Scotto, Sills, and, more recently, Sondra Radvanovsky have had success with it, but none has really challenged the supremacy of Callas and Sutherland. Now that the age of expensive studio opera recordings is largely over in favour of recording live or concert performances, and given that there seemed to be little commercial or artistic rationale for producing another recording to challenge those already in the catalogue, the appearance of the new Bartoli recording was a surprise, but it sought to justify its existence via the claim that it authentically reinstates the integrity of Bellini’s original concept in matters such as voice categories, ornamentation and instrumentation. -

Constructing the Archive: an Annotated Catalogue of the Deon Van Der Walt

(De)constructing the archive: An annotated catalogue of the Deon van der Walt Collection in the NMMU Library Frederick Jacobus Buys January 2014 Submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Master of Music (Performing Arts) at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Supervisor: Prof Zelda Potgieter TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DECLARATION i ABSTRACT ii OPSOMMING iii KEY WORDS iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION TO THIS STUDY 1 1. Aim of the research 1 2. Context & Rationale 2 3. Outlay of Chapters 4 CHAPTER 2 - (DE)CONSTRUCTING THE ARCHIVE: A BRIEF LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CHAPTER 3 - DEON VAN DER WALT: A LIFE CUT SHORT 9 CHAPTER 4 - THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION: AN ANNOTATED CATALOGUE 12 CHAPTER 5 - CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 18 1. The current state of the Deon van der Walt Collection 18 2. Suggestions and recommendations for the future of the Deon van der Walt Collection 21 SOURCES 24 APPENDIX A PERFORMANCE AND RECORDING LIST 29 APPEDIX B ANNOTED CATALOGUE OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION 41 APPENDIX C NELSON MANDELA METROPOLITAN UNIVERSTITY LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SERVICES (NMMU LIS) - CIRCULATION OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT (DVW) COLLECTION (DONATION) 280 APPENDIX D PAPER DELIVERED BY ZELDA POTGIETER AT THE OFFICIAL OPENING OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION, SOUTH CAMPUS LIBRARY, NMMU, ON 20 SEPTEMBER 2007 282 i DECLARATION I, Frederick Jacobus Buys (student no. 211267325), hereby declare that this treatise, in partial fulfilment for the degree M.Mus (Performing Arts), is my own work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment or completion of any postgraduate qualification to another University or for another qualification.