Final Evaluation by a Team of External Consultants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promoting Sustainable Agriculture in Samroung Commune, Prey Chhor District, Kampong Cham Province Through Network of RCE Greater Phnom Penh

Promoting Sustainable Agriculture in Samroung Commune, Prey Chhor District, Kampong Cham Province through Network of RCE Greater Phnom Penh Saruom RAN Cambodia Branch, Institute of Environment Rehabilitation and Conservation, Phnom Penh, Cambodia Email: [email protected] Kanako KOBAYASHI Extension Center, Institute of Environment Rehabilitation and Conservation, Tokyo, Japan Lalita SIRIWATTANANON Rajamangala University of Technology Thanyaburi, Pathum Thani, Thailand / Southeast Asia Office, Institute of Environment Rehabilitation and Conservation, Pathum Thani, Thailand Machito MIHARA Institute of Environment Rehabilitation and Conservation, Tokyo, Japan / Faculty of Regional Environment Science, Tokyo University of Agriculture, Tokyo, Japan Bunthan NGO Royal University of Agriculture, Phnom Penh, Cambodia / Institute of Environment Rehabilitation and Conservation, Tokyo, Japan Abstract: Agriculture is one of the important sectors in Cambodia, as more than 70 percent of populations are engaging in the agricultural sector. Phnom Penh is the capital of Cambodia having more than 1.3 million people. RCE Greater Phnom Penh (RCE GPP) was established in December 2009 to promote ESD in Cambodia. RCE Greater Phnom Penh covers not only Phnom Penh but also surrounding provinces, such as Kampong Cham, Kampong Chhnang, Kampong Speu, Kandal, Prey Veng and Takeo. Recently, in Kampong Cham province of Cambodia, subsistence agriculture tends to be converted to mono-culture. Also, more that 60 percent of farmers have been applying agricultural chemicals without understanding the impact on health and food safety. It is necessary to promote and enhance the understanding of sustainable agriculture among local people including farmers and elementary school students, as the students are the successors of local farmers. So, attention has been paid to Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in the agricultural sector for achieving food safety, conserving environment and reducing expense for agricultural chemicals in Kampong Cham province. -

Urbanising Disaster Risk

Ben Flower and Matt Fortnam URBANISING DISASTER RISK PEOPLE IN NEED IN PEOPLE VULNERABILITY OF THE URBAN POOR IN CAMBODIA TO FLOODING AND OTHER HAZARDS Copyright © People in Need 2015. Reproduction is permitted providing the source is visibly credited. This report has been published by People in Need mission in Cambodia and is part of “Building Disaster Ressilient Communities in Cambodia II“- project funded by Disaster Preparedness Program of Eureopan Commission Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection (DIPECHO). The project is implemented by a consortium of five international organisations: ActionAid, DanChurchAid/ Christian Aid, Oxfam, People in Need and Save the Children. Disclaimer This document covers humanitarian aid activities implemented with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein should not be taken, in any way, to reflect the official opinion of the European Union, and the European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. Acknowledgment People in Need would like to thank all the organisations and individuals which provided Piotr Sasin support and input throughout the research of this report. In particular we want to Country Director thank: National Committee for Disaster Management, Municipality of Phnom Penh, People in Need Municipality of Kampong Cham, Japan International Coopeation Agency, Mekong River Cambodia Commission, Urban Poor Women Development, Community Development Fund and June 2015 Sahmakum Teang Tnaut. Our special thanks go to urban -

Gods of Angkor: Bronzes from the National Museum of Cambodia

Page 1 OBJECT LIST Gods of Angkor: Bronzes from the National Museum of Cambodia At the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center February 22 — August 14, 2011 1. Maitreya 3. Buddha Cambodia, Angkor period, early Cambodia, pre Angkor period, 10th century second half of 7th century Bronze; 75.5 x 50 x 23 cm (29 3/4 x Bronze; figure and base, 39 x 11.5 x 19 11/16 x 9 1/16 in.) 10.5 cm (15 3/8 x 4 1/2 x 4 1/8 in.) Provenance: Kampong Chhnang Provenance: Kampong Cham province, Wat Ampil Tuek; acquired province, Cheung Prey district, 21 September 1926; transferred Sdaeung Chey village; acquired from Royal Library, Phnom Penh 2006 National Museum of Cambodia, National Museum of Cambodia, Phnom Penh, Ga2024 Phnom Penh, Ga6937 2. Buddha 4. Buddha Cambodia, pre Angkor period, 7th Cambodia, pre Angkor period, century second half of 7th century Bronze; 49 x 16 x 10 cm (19 5/16 x Bronze; 14 x 5 x 3 cm (5 1/2 x 1 6 5/16 x 3 15/16 in.) 15/16 x 1 3/16 in.) Provenance: Kampong Chhnang Provenance: Kampong Cham province, Kampong Leaeng district, province, Cheung Prey district, Sangkat Da; acquired 11 March Sdaeung Chey village; acquired 1967 2006 National Museum of Cambodia, National Museum of Cambodia, Phnom Penh, Ga5406 Phnom Penh, Ga6938 -more- -more- Page 2 5. Buddha 9. Vajra bearing Guardian Cambodia, pre Angkor period, China, Sui or Tang dynasty, late 6th second half of 7th century 7th century Bronze; figure and base, 25 x 8 x 5 Bronze with traces of gilding; 15 x 6 cm (9 13/16 x 3 1/8 x 1 15/16 in.) x 3 cm (5 7/8 x 2 3/8 x 1 3/16 in.) Provenance: Kampong Cham Provenance: Kampong Cham province, Cheung Prey district, province, Cheung Prey district, Sdaeung Chey village; acquired Sdaeung Chey village; acquired 2006 2006 National Museum of Cambodia, National Museum of Cambodia, Phnom Penh, Ga6939 Phnom Penh, Ga6943 6. -

41403-013: Resettlement Due Diligence Report Kampong Cham

Resettlement Due Diligence Report September 2014 CAM: Urban Water Supply Project – Kampong Cham Subproject Prepared by the Ministry of Industry and Handicraft for the Asian Development Bank. This Due Diligence Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or Staff and may be preliminary in nature. t ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank APs - Affected Persons DPWS - Department of Potable Water Supply EA - Executing Agency HDPE - High-density polyethylene JICA - Japan International Cooperation Agency para - paragraph PIACs - Project Implementation Assistance Consultants PIB - Project Information Brochure PIU - Project Implementation Unit PMU - Project Management Unit Project - Urban Water Supply Project PSMO - PMU Safeguards Management Officer RGC - Royal Government of Cambodia ROW - Right-of-Way UWSP - Urban Water Supply Project TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACCRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………….. 1 A. Overview ………………………………………. 1 B. Current Status………………………………….. 1 C. Rationale for Due Diligence…………………... 1 II. PROPOSED SUBPROJECT INVESTMENT……… 2 III. APPROACH TO DUE DILIGENCE……………….. 2 IV. FINDINGS OF THE DUE DILIGENCE………………. 2 A. Infrastructures in Existing Site……………….. 3 B. Infrastructures in the Distribution Networks… 3 C. Infrastructures in the Proposed Station 3…… 3 V. PROJECT DISCLOSURE AND CONSULTATION. 4 VI. IMPLEMENTATION ARRANGEMENT……………. 5 A. Institutional Arrangement……………………... 5 Attachments: Attachment 1: Agreement on Shifting Property Attachment 2: Attendance in Public Consultation Attachment 3: Project Information Brochure (English) I. INTRODUCTION A. Overview 1. The Urban Water Supply Project (UWSP, or the Project) at Kampong Cham City, in Kampong Cham Province, is among the nine (9) subprojects being proposed for the improvement and expansion of urban water supply services of public waterworks in selected provincial towns in Cambodia1. -

Peace Corps Cambodia Annual Report 2017

Peace Corps Cambodia Annual Report 2017 Peace Corps Cambodia | Table of Contents 11 Years of Partnership and Service iii Our Vision and Values iii Message from the Country Director 1 Peace Corps Global Overview 2 Peace Corps in Cambodia 3 Cambodian Government Support 4 Our Volunteers Todayy 5 English Teaching and Teacher Training Program 6 Education Accomplishments in 2017 7 Education Success Stories 8 What Peace Corps Volunteers are Doing 10 Community Health Education 12 Health Accomplishments in 20177 13 Health Success Stories 14 Small Grants Program and Accomplishments 16 Small Grants Success Stories 18 Homestay Experience 202 i 11 YEARS of partnership and 5 7 3 Volunteers have served in service at a glance 19 of Cambodia’s 25 cities and provinces since 2007 K11 Swearing-in t Battambang t Kratie t Takeo 71 Volunteers, 34 in t Kampong Cham t Prey Veng t Tbong Khmum 2017 Educaton and 37 in Health, t Kampong Chhnang t Pursat swear in on September 15, t Kampong Thom t Siem Reap 2017 and serve in: t Kampot t Svay Rieng K10 Swearing-in t Banteay Meanchey t Kampong Thom t Siem Reap 69 Volunteers, 34 in t Battambang t Kampot t Svay Rieng 2016 Educaton and 35 in Health, t Kampong Cham t Koh Kong t Takeo swear in on September 16, t Kampong Chhnang t Prey Veng t Tbong Khmum 2016 and serve in: t Kampong Speu t Pursat K9 Swearing-in t Banteay Meanchey t Kampong Thom t Siem Reap 63 Volunteers, 34 in t Battambang t Kampot t Svay Rieng 2015 Education and 29 in Health, t Kampong Cham t Koh Kong t Takeo swear in on September 25, t Kampong Chhnang t -

Index Map 1-2. Provinces and Districts in Cambodia

Index Map 1-2. Provinces and Districts in Cambodia Code of Province / Municipality and District 01 BANTEAY MEANCHEY 08 KANDAL 16 RATANAK KIRI 1608 0102 Mongkol Borei 0801 Kandal Stueng 1601 Andoung Meas 2204 0103 Phnum Srok 0802 Kien Svay 1602 Krong Ban Lung 1903 0104 Preah Netr Preah 0803 Khsach Kandal 1603 Bar Kaev 2202 2205 1303 2201 0105 Ou Chrov 0804 Kaoh Thum 1604 Koun Mom 1609 0106 Krong Serei Saophoan 0805 Leuk Daek 1605 Lumphat 0107 2203 0107 Thma Puok 0806 Lvea Aem 1606 Ou Chum 0108 Svay Chek 0807 Mukh Kampul 1607 Ou Ya Dav 1302 1601 0109 Malai 0808 Angk Snuol 1608 Ta Veaeng 1307 0110 Krong Paoy Paet 0809 Ponhea Lueu 1609 Veun Sai 0103 1714 1606 0108 1712 0810 S'ang 1304 1904 02 BATTAMBANG 0811 Krong Ta Khmau 17 SIEM REAP 1308 0201 Banan 1701 Angkor Chum 1701 1602 1603 1713 1905 0202 Thma Koul 09 KOH KONG 1702 Angkor Thum 0110 0105 1901 0203 Krong Battambang 0901 Botum Sakor 1703 Banteay Srei 0106 0104 1706 1702 1703 1301 1607 0204 Bavel 0902 Kiri Sakor 1704 Chi Kraeng 0109 1604 0205 Aek Phnum 0903 Kaoh Kong 1706 Kralanh 0102 1707 1306 1605 0206 Moung Ruessei 0904 Krong Khemarak Phoumin 1707 Puok 0210 0207 Rotonak Mondol 0905 Mondol Seima 1709 Prasat Bakong 1710 1305 0208 Sangkae 0906 Srae Ambel 1710 Krong Siem Reab 0211 1709 0209 Samlout 0907 Thma Bang 1711 Soutr Nikom 0202 0205 0204 1711 1902 0210 Sampov Lun 1712 Srei Snam 1704 0211 Phnom Proek 10 KRATIE 1713 Svay Leu 0212 0203 0212 Kamrieng 1001 Chhloung 1714 Varin 0213 Koas Krala 1002 Krong Kracheh 0208 0604 0606 1102 0214 Rukhak Kiri 1003 Preaek Prasab 18 PREAH SIHANOUK -

Royal Government of Cambodia Department of Pollution Control Ministry of Environment

Royal Government of Cambodia Department of Pollution Control Ministry of Environment Project titled: Training Courses on the Environmentally Sound Management of Electrical and Electronic Wastes in Cambodia Final Report Submitted to The Secretariat of the Basel Convention August-2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF APPENDICES.......................................................................................3 LIST OF ACRONYMS.........................................................................................4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.....................................................................................5 REPORT OF PROJECT ACTIVITIES.................................................................6 I. Institutional Arrangement.......................................................................6 II. Project Achievement...........................................................................6 REPORT OF THE TRAINING COURSES..........................................................8 I- Introduction............................................................................................8 II Opening of the Training Courses...........................................................9 III. Training Courses Presentation...........................................................10 IV. Training Courses Conclusions and Recommendations.....................12 V. National Follow-Up Activities..............................................................13 2 LIST OF APPENDICES Appendix A: Programme of the Training Course Appendix B: List -

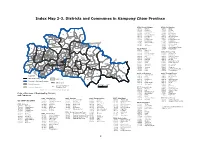

Map 2-3. Districts and Communes in Kampong Cham Province

Index Map 2-3. Districts and Communes in Kampong Cham Province 0309 Krouch Chhmar 0314 Srei Santhor 030901 Chhuk 031401 Baray 030902 Chumnik 031402 Chi Bal 030903 Kampong Treas 031403 Khnar Sa 06 14 030904 Kaoh Pir 031404 Kaoh Andaet 03 01 030905 Krouch Chhmar 031405 Mean Chey 08 030906 Peus Muoy 031406 Phteah Kandal 04 05 0315 04 030907 Peus Pir 031407 Pram Yam 02 030908 Preaek A chi 031408 Preaek Dambouk 05 10 07 03 08 030909 Roka Khnor 031409 Preaek Pou 06 030910 Svay Khleang 031410 Preaek Rumdeng 05 11 10 030911 Trea 031411 Ruessei Srok 07 12 02 07 09 030912 Tuol Snuol 031412 Svay Pou 0302 13 06 08 031413 Svay Khsach Phnum 05 09 11 06 0309 0310 Memot 031414 Tong Tralach 01 13 08 01 031001 Chan Mul 02 13 02 04 12 05 07 06 05 0306 031002 Choam 0315 Stueng Trang 10 03 031003 Choam Kravien 031501 Areaks Tnot 0303 15 12 12 01 10 03 15 031004 Choam Ta Mau 031503 Dang Kdar 10 09 10 09 14 0304 0313 16 07 04 12 04 07 11 031005 Dar 031504 Khpob Ta Nguon 03 09 11 02 02 05 08 07 0316 031006 Kampoan 031505 Me Sar Chrey 06 03 11 08 01 21 01 04 14 02 031007 Memong 031506 Ou Mlu 02 15 01 05 06 031008 Memot 031507 Peam Kaoh Snar 11 03 12 0301 0305 02 031010 Rung 031508 Preah Andoung 01 09 06 04 03 06 01 07 04 04 05 06 031011 Rumchek 031509 Preaek Bak 22 0317 13 0310 02 03 11 08 08 05 0307 13 04 02 01 031013 Tramung 031510 Preak Kak 03 05 01 04 14 18 06 16 07 031014 Tonlung 031512 Soupheas 08 08 06 07 07 01 04 14 07 02 08 10 0308 031015 Triek 031513 Tuol Preah Khleang 10 03 0311 09 06 04 04 04 031016 Kokir 031514 Tuol Sambuor 0314 08 01 07 09 08 05 -

3. Present Situation and Issues of Rural Electrification

Final Report (Master Plan) Vol 2 Part 1 Chapter 3 3. PRESENT SITUATION AND ISSUES OF RURAL ELECTRIFICATION 3.1 OUTLINE OF POWER SUPPLY IN CAMBODIA Electricity was introduced in Cambodia first in the year 1906. Up to the year 1958, electricity in Cambodia was supplied by the three (3) private companies, namely CEE, UNEDI and CFKE. At the time, CEE supplied electricity to Phnom Penh and its surrounding areas and UNEDI to all provinces except for Battambang, which was supplied by CFKE. In 1958, the Government took over CEE and UNEDI and established a new state-own enterprise called as EdC. In 1958, total installed capacity in the country was approximately 30 MW, of which 16 MW was owned by EdC and others by private companies. In 1970, total installed capacity of EdC reached 61 MW, 68.5% of the total capacity of the country (79 MW). During 1971 to 1979, the power sector in the country passed through two dangerous events: social disorder triggered by a coup d'etat (1971-1975) and turbulent history during the Pol Pot Regime (1975- 1979). During this time, all kinds of generation, transmission and distribution facilities were destroyed not only in Phnom Penh but also in other areas. After the liberation in 1979, the Government started to restore the electricity infrastructure in the capital town and main provincial towns of the country. At that time, the whole electricity supply in the country was under management of the Ministry of Industry. The Government re-established EdC with the task of electricity supply in Phnom Penh and established small enterprises in provinces with the responsibility to supply electricity in each province. -

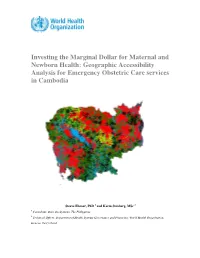

Geographic Accessibility Analysis for Emergency Obstetric Care Services in Cambodia

Investing the Marginal Dollar for Maternal and Newborn Health: Geographic Accessibility Analysis for Emergency Obstetric Care services in Cambodia Steeve Ebener, PhD 1 and Karin Stenberg, MSc 2 1 Consultant, Gaia GeoSystems, The Philippines 2 Technical Officer, Department of Health Systems Governance and Financing, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland Geographic Accessibility Analysis for Emergency Obstetric Care services in Cambodia © World Health Organization 2016 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO website (http://www.who.int ) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected] ). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications –whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution– should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website (http://www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/index.html ). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. -

Ground-Water Resources of Cambodia

Ground-Water Resources of Cambodia GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER I608-P Prepared in cooperation with the ^<ryr>s. Government of Cambodia under the t auspices of the United States Agency rf for International Development \ Ground-Water Resources of Cambodia By W. C. RASMUSSEN and G. M. BRADFORD CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF ASIA AND OCEANIA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1608-P Prepared in cooperation with the Government of Cambodia under the auspices of the United States Agency for International Development UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1977 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Rasmussen, William Charles, 1917-73 Ground-water resources of Cambodia. (Geological Survey water-supply paper; 1608-P: Contributions to the hydrology of Asia and Oceania) "Prepared in cooperation with the Govern ment of Cambodia under the auspices of the United States Agency for International Development." 1. Water, Underground Cambodia. I. Bradford, G. M., joint author. II. Cambodia. III. United States. Agency for International Development. IV. Title. V. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Water-supply paper ; 1608-P. VI. Series: Contributions to the hydrology of Asia and Oceania. TC801.U2 no. 1608-P [GB1144.C3] 627'.08s [553'.79'09596] 74-20781 For sale by the Branch of Distribution, U.S. Geological Survey, 1200 South Eads Street, Arlington, VA 22202 CONTENTS Page Abstract __________________________________________ -

Disaster Profile of Cambodia (2005 – 2017)

DISASTER PROFILE OF CAMBODIA (2005 – 2017) 1. DISASTER PROFILE Figure 1 and Table 1 showed the number of data cards or records for each type of hazard from 2005 - 2017. There were eight most frequently reported disaster events represented in the pie chart: flood, fire, storm, lightning, drought, pest outbreak, epidemic, and river bank collapse. The hazard reported to be occurred the most frequently was flood, with a total of 3,052 data cards, representing 38% reported between 2005-2017; followed by fire with 1,877 data cards (23.25%); storm 1,414 (17.25%); lightning 893 (11%); drought 581 (7%); pest outbreak 85 (1%); others included epidemic 56 (1%) and river bank collapse 48 (1%). Figure 1: Disaster Topology Table 1: Frequency and Percentage of Disaster by Data Card (2005 - 2017) No. Disaster Data Cards Percentage 1 Flood 3,052 38 2 Fire 1,877 23.5 3 Storm 1,414 17.5 4 Lightning 893 11 5 Drought 581 7 6 Pest Outbreak 85 1 7 Epidemic 56 1 8 River Bank Collapse 48 1 TOTAL 7,389 100 Page 1 of 14 Consolidated By: H.E. Ma Norith, Deputy Secretary-General (NCDM), March 2018 Spatial Distribution of Disaster Figure 2 below showed the distribution of data cards or records of disaster events across the 25 Provinces and Cities in Cambodia. The top five provinces with most report cards were Siem Reap with the total of 1,184; followed by Kampong Cham (709); Kratie (499); Battambang (492); and Prey Veng (470). Figure 2: Spatial Map: Number of Data Card (2005 - 2017) Page 2 of 14 Consolidated By: H.E.